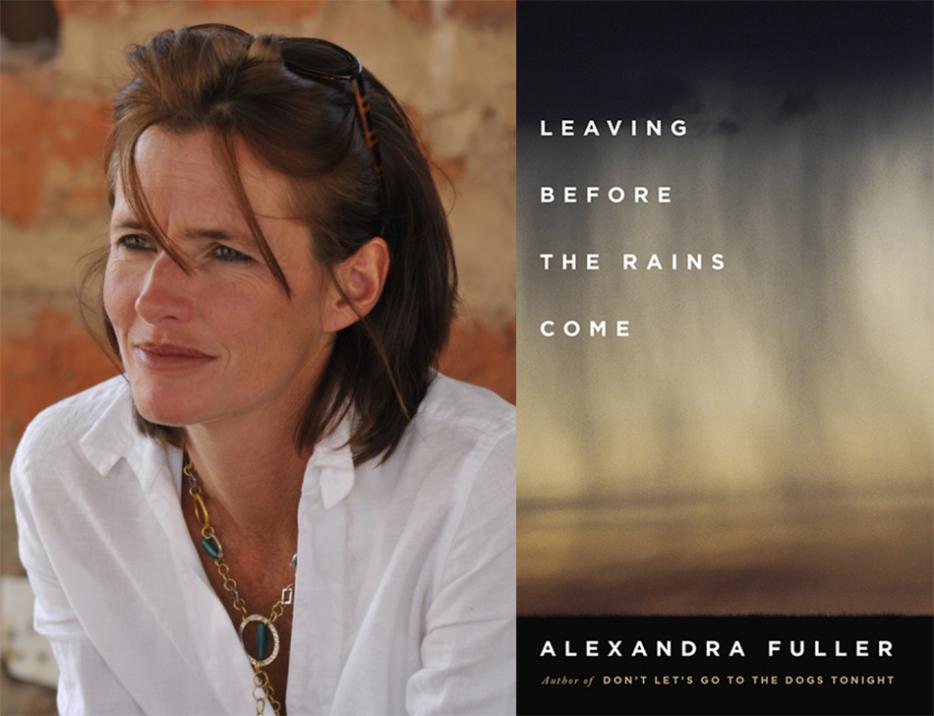

When we meet in Toronto to discuss her new memoir Leaving Before The Rains Come, Alexandra Fuller seems a bit defensive about reviews that describe it as a memoir about divorce. “It’s really not a book about two people in a relationship,” she said. And she’s right. It’s more solitary; the book captures the silence that overtakes the end of a marriage, and Fuller’s determination to become “noisy” again, as an independent and passionately outspoken woman.

Fuller, who was raised on a farm in the violence and vividness of post-colonial Zambia, had no clue about money, mortgages or even how to write a cheque when she moved to America 20 years ago. She had met her husband, a tall and dashing river guide named Charlie Ross, while he was operating tours in Zambia; they soon moved to his home turf of Wyoming. It’s fascinating that someone who grew up with black mamba snakes sneaking into the pantry and a bloody civil war going on down the road could be so rattled by the hidden dangers of living the American Dream.

As Fuller kept house, kept silent and raised her three children, she also got up at 4 every morning to write. She produced nine novels, all rejected by publishers, until she gave up and began to write a memoir about the chaos, beauty and danger of her childhood in Rhodesia (as it morphed into Zimbabwe) with her gin-swigging, gun-toting, life-loving parents.

Published in 2001, Don’t Let’s Go To the Dogs Tonight has joined the short shelf of classic memoirs that includes Mary Karr’s Liars’ Club and Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness followed, with the focus on her mother, Nicola Fuller. Her deep love of the country where she grew up is still tangible in this fourth memoir, whenever she returns to Zambia to visit her parents.

It’s a tricky business, writing honestly about the people closest to you, and Fuller has erred on the side of protecting her family’s privacy. If the character of her ex-husband Charlie remains shadowy in Leaving Before The Rains Come (apart from one scene in which he stands up to a charging elephant), that is exactly as Fuller wants it.

But the book is vibrant with indignation at the delusions and compromises that underpin the good life in America.

Fuller continues to live in Wyoming where she has been active in protecting the environment from oil interests. She has a new partner, a social insurance number, and says she no longer feels African. But every time she describes a visit to her childhood home, her nimble, feminine, intelligent writing jumps into even sharper focus, as if seen through the crosshairs of a gun.

Here is my conversation with Alexandra Fuller.

*

Your first two memoirs were about your parents, and their lives as British expats in southern Africa—a landscape which became a character in itself. But in this new book, the focus is more on you.

Everyone ignores the memoir in which I went back to Mozambique with a soldier from the war I grew up in—

Yes. Everyone really hated that book except for my mother, which was my clue that I hadn’t written about her, and that, really, it was about me. She hated the first book and tolerated the second one. I love to point out that there was another memoir in there that really was about me. It’s about what war does to children. It’s about what happens to an 18-year-old boy when he gets sent to war. It’s about what happens to an eight-year-old girl who watches those boys go to war. It’s what happens afterwards and that book is very important to me. It doesn’t let everyone off the hook. There isn’t the same distancing and the ability to “other” in there. But anyway, I’ll let you skip over it just as everybody else does.

With this book about your divorce, you are really on the hot seat, front and centre. Was this memoir harder to write?

It was brutal for a lot of reasons, because this really is a book about me—about a woman who’s being noisy. Putting yourself in the centre, you have to be both ruthless to yourself, about yourself, and almost unnaturally fair to everyone around you.

Did writing about your divorce impose a self-consciousness about whether you were treating your ex-husband fairly?

Yeah, that’s why this book became an anti-divorce divorce memoir, because it’s really not a book about two people in a relationship. It felt incredibly unfair to use the privilege of that sort of intimacy to expose someone else, someone whom you’ve gone into an adult, consenting relationship with. That’s not true of your parents, it’s not true of your culture and it’s not true of your people. I think every writer, if you’re going to write anything real, needs to court eviction from their tribe. Otherwise you are really just crippled.

As Joan Didion said, “Writers are always selling somebody out.”

Funnily enough, she was a model for me while writing this book, because she’s almost icily circumspect. You really don’t get a sense of the other people in her story. I was reading The Year of Magical Thinking as a form of solace, because she seemed to havesuch emotional abstinence. I can’t do that. I seem to be lacking the enzymes that want to protect my privacy, but I understand that I have an ethical obligation to protect the privacy of my ex-husband and also, especially, my children.

When you write so personally, how do you protect yourself when readers come up to you and say “I feel like I know you?”

I say thank you, or, “Aw, that’s nice.” It’s not true, but it’s nice to think that you’re not all alone on this journey. But just as much as you get the response “I’ve been with you and I love your books, they’re by my bedside,” you increasingly get violent opposition in the Internet world.

Moral judgers and haters?

It’s stronger than that—more like threatening, really violently angry people. I do think that one day there’s going to be a study that suggests that when women speak out, it really riles people.

You’re opening yourself up, sharing your whole life on the page with readers. Maybe that comes across as too powerful for some people.

Also, in every single book that I’ve done, the response has been, “Why did she have to go and expose that”—the racism that I grew up with, what happens to soldiers after war, what happens on oil rigs in Wyoming when we are busy consuming oil, what happens to children of a colonial regime and the violence that they can perpetuate. In this book, I’m exposing what happens when a woman decides that she can no longer exist in the kind of isolated confinement that a lot of marriages become for women. I love that Kafka line, “In writing you should take an ax to the frozen sea inside.” That’s really my target. But I think a lot of people mistake that act, which for me is crucial in writing, with a kind of confessional, therapeutic impulse.

“Airing your dirty laundry.”

Yeah. And generally people who throw those words around haven’t read my work. My writing is hard work because it isn’t therapeutic. It’s not cathartic, it’s challenging, and what I’m really saying to the reader is what lovely Charles Wright says in his poem “Light Foot.” I’m going to paraphrase it incorrectly, but it’s something like, “the only journey that matters is the journey to the interior.” It’s okay that my children and my ex-husband become place marks and ciphers for the thing that I know better, and the thing I’m more interested in exploring, which is a woman’s journey.

At one point in the book, your husband, Charlie Ross, says you’re always taking things too far. Do you think you do?

Yeah, that seems fair.

Is that part of your job as writer?

Look, the job of a writer is not to put everyone to sleep. You’re not an anesthesiologist, for heaven’s sake. But I could very understandably be accused of self-reflection to the point of mania. I have put the “me” into memoir at this point. I was trying to think of a defence for that: who would be so self-involved to write four memoirs? Then I looked around and saw how hard people were working not to be self-involved. They’re listening to their iPods; they’re knitting and driving at the same time, doing anything to not sit still with the self. Part of the process of writing this book for me was several ten-day stretches of silent meditation, 14 hours at a time. No eye contact, no touching, no writing and no reading. You just meditate. You certainly take the journey to the interior, and it’s brutally difficult.

Does the world really need another memoir by another divorced white woman? The answer is no, not at all, but if the question is, does the world need room for women to tell their truth? Then the answer is yes.

Mary Karr, the author of the classic memoir Liar’s Club, also wrote her first wonderful family memoir from a young girl’s point of view. She went on to publish other popular memoirs, but I felt her writing lost the urgency and honesty of that first book. This is your fourth memoir. How do you keep the writing and self-scrutiny true?

I think it’s just that repeated journey to the interior, being ruthless with yourself and making sure that you’re showing up in an authentic way. Maybe it’s this great gift of becoming older, because now I’m in my late forties and it’s wonderful. God, yay for wrinkles and grey hair! Now when I curse horribly they’ll say, “Wow, that old lady is really letting it rip.”

You write so passionately about the environment, and the connection between “the soul and the soil” in your African memoirs. What’s your connection now with the landscape of Wyoming, where Leaving Before The Rains Come is set?

I think that connection is overwhelming for me. It’s constant, it doesn’t matter where I go. A lot of people like to sort of talk about this fact that I have this romantic attachment to Southern Africa, Zimbabwe or Zambia, and now Wyoming, but both those places are being exploited. I think whatever soil you’re standing on, I don’t care if you’re in Salt Lake City or Toronto or Lusaka, you have a duty and obligation to fight for whatever patch of earth there is. It’s not going to get easier unless we do. A lot of the impetus for this book, though it keeps getting touted as this divorce memoir, is really about that. It’s about standing up for yourself not in a selfish self-loving kind of way, but in the example of people like Wangari Mathai, the great Kenyan peace activist who won a Nobel Peace Prize. Her point is that if you stand up for yourself with enough dignity and enough compassion and enough integrity, you will by default stand up for everybody’s social justice, everybody’s environmental justice.

I was interviewing Wangari for a piece I was doing for Vogue (unfortunately she died far too soon). I was in awe of the fact that she really pushed, she really pushed it: she was imprisoned, she was hospitalized for her defence of wild lands and of peoples’ voices, her children were taken from her, her husband divorced her, she lost her job. And still, she laughed so much. She refused to be a victim in all of this. I asked her, “How do you do it?” And she said, “Sometimes when your system or your culture is so wrong, it’s you who will look wrong when you are doing the right thing.” I think that’s the case when you acknowledge your conscience and really think about what it is you’re doing. Why are you on the planet? Does the world really need another memoir by another divorced white woman? The answer is no, not at all, but if the question is, does the world need room for women to tell their truth? Then the answer is yes.

You write that in order for a woman to speak her mind, she must first possess it. Do you feel you are there?

I’ll let you know. I think that’s a behest, but for me anyway, you have to recognize your own privilege. If we don’t then I think we are doing a disservice for those who are actually fighting for privilege and sovereignty and agency on so many other levels. But I think it’s such hard work for us to examine our own privilege, because what it tells us is that you didn’t just get here through your own hard work, you got here because you started a half inch away from the finish line. Some start at the finish line. And if I don’t use my freedom or the voice I have been given because of the privilege, what are the chances for black African women, only 1 in 10 of whom will even make it out of elementary school? I got an education, a great education, I’ve had support, and I’ve been able to fly under the radar as an immigrant in the U.S. because I’m not Hispanic or Latino.

You fell in love with southern Africa and have an ongoing romance with that country. When you met your future husband, who was working as a river guide in Zambia, you married and moved to Wyoming with him. Did you have a romance with America too?

No, I really didn’t. No, no, no. I had no desire to leave Africa, none, none, and none. It was a glandular decision; I fell in love with him. It didn’t even override the love of the land. I made the mistake of believing that he would want to stay in Africa with me. I mean, how could you leave? This was the first love of my life. Which was sort of the model my parents had—they loved the land first and their love of each other is very much based on that common love. They were passionately, dangerously, murderously in love with that land. It really made me realize that a shared culture, a shared understanding of that is enormous.

There’s quite a shift in the character of your husband, from the dashing guy who looks good on a horse in Zambia, to the rather quiet, careworn husband who ends up working as a realtor in Wyoming. For a long time you tell yourself, “This is just the ordinariness of marriage setting in,” without realizing that it’s not working.

I had such an impossible model to follow, which was my parents, because they really didn’t fall into ordinariness. What has been so astounding for me about their marriage is this cultivated delight they take in each other. In other words, it takes effort. To shriek with laughter at each other’s foibles instead of what most people who have been married for fifty years do—roll their eyes.

So it’s falling in love with the foibles and the flaws and the craziness of the other, as well as their strengths.

Right, and the deep sanity and the commitment and the history. I think the one thing that so many people tolerate in marriage is the solitary confinement of silence. It became such a trauma for me. My parents are operatic in their marriage. They find each other delightful. When they fight, they fight. You may as well get it out of the way and then there will be some passionate lovemaking, which is not necessarily what you want to know about your parents when they are in their 70s. They live in a house with dissolving brick mud walls, so there are not a lot of secrets. Their passion for each other is not secret.

The last time I was home, there were crocodiles eating the fish in my mother’s fishpond and so my dad got his gun out. He can’t actually kill a crocodile with a gun, but he said he could certainly make it stop eating my mother’s fish. There was this love in her eyes as she said, “That’s you, Tim, go on, tell them off.” And off he marched saying, “This one’s for you, Tub.” There’s just this real delight, night after night.

I look at those bumper stickers that say, “Well behaved women rarely make history,” and I think, That’s a great bumper sticker. Then you see the woman driving: up since 4 a.m. writing her ninth rejected novel, three kids screaming, she looks absolutely harried, she put something in the stove before she left and she’s going to come home and clean. I feel like going and tapping on the window and saying, "Bumper-sticker feminism isn’t feminism."

Every time you return to Africa in this book, a sense of joy and vitality leaps out again, in contrast to your life in Wyoming.

One of the contracts I have with my children and my current partner is that I will not negotiate by withdrawing. This feels to me like a very, dare I say, white American male position: I’m going to just withdraw and you’re hysterical and that’s it. And that silence is somehow a superior position. I was listening to that wonderful Suzanne Vega song, “There’s Nothing I Hate More Than Nothing,” and I finally went, fuck this. I realized, this will kill me; it’s eating me up inside. This silence is so violent and one of us is going to get hurt.

The showstopper for me in the book was learning that while taking care of three children and a house, you had been getting up at 4 in the morning to write. You completed not just one, not two, but nine novels—all of which were rejected.

That’s what women do. I look at those bumper stickers that say, “Well behaved women rarely make history,” and I think,That’s a great bumper sticker. Then you see the poor woman driving the car: she’s been up since 4 in the morning writing her ninth rejected novel, she’s got three kids screaming in the back, she looks absolutely harried, she put something in the stove before she left and she’s going to come home and clean the house. I just feel like going and tapping on the window and saying bumper-sticker feminism isn’t feminism.

I would love it if all women just had a big old lie-in. Guess what, today you are not getting laid or fed or pretty much anything. I’m lying here and we’ll just see the world grind to a halt. Water won’t be fetched, firewood won’t be chopped, children’s diapers won’t be changed, and the world will go into a halt. All I’m saying is that if men had to go and pump their breasts in twenty minutes on their work break, life would be very different. If football players had to take a knee and accept that somebody on the field had cramps because it was their period, it would be a very different world.

But you’re light-hearted about the work of motherhood in the book.

Doris Lessing said early on that having young toddlers was for her the Himalayas of tedium. I think women are running themselves ragged, like men without a penis running around in power suits, still doing it all.

There’s a lot more questioning now of the having-it-all premise. Nobody can have it all.

No, it’s absolute bullshit.

I think you should have your own late-night talk show, frankly.

I do too, and my lover says, “I’m going to give you a sleeping pill.”

What do you think of marriage now?

I’m very outspoken on the issue of marriage equality in Wyoming because our idiot governor is like all the other prehistoric governors who are crawling out of the swamps of the south and the Midwest, declaring that the Bible says men can’t marry men and women can’t marry women. I say, you know what, if you find that partnership and you have a respect for one another and it involves a contract of love, then go for it. I am the first person to cry at your wedding. But I think were I to marry my current partner, whom I have a great deal of respect for, my marriage vows would be very different. It would be an understanding that yes, we drink from the same creative well. Both of us need to understand that life is a creative process, that I will not negotiate by withholding, that I bring to our meeting place an open heart and that I don’t expect you to be everything to me. I think that it is important that we try and listen to one another, though I won’t countenance being lectured by the establishment who have objectively screwed things up. We are in long entrenched wars, our environmental situation is catastrophic, our economic justice is woeful, our health care system in the States is non-existent. For me, marriage is the tiny beginning conversation for these much bigger problems. I don’t expect you to be all things for me, but I expect you to hear me, I expect to be visible and I expect respect.

You also want someone who laughs at your jokes, right?

Desperately. No, seriously, that’s number one on the list. Actually, number one is: do you believe in the death penalty? If the answer to that is yes, then I’m done.

That’s a good opening line at a bar.

It’s not really a pickup line. It’s more of a “drop line.” Nope, done. Next?

What other qualifications in a potential husband?

I would crack a joke and see if they smiled or laughed. Life’s absurd for heaven’s sake, you might as well shriek with laughter at it.

Your mother seems like a good role model on that front.

And she’s getting worse and worse, or better and better, whichever way you look at it. It was a little shocking to her when I exposed the racism I grew up with, but I think that’s the job of the writer. You’re not supposed to numb people and pretend that everything is ok.

Well, your family are the last people who are going to like your memoir.

The great thing about my family is that I was raised in this way, which is why I’m so outspoken, because I just assumed no one cared. I feel very loved and supported by versions of them. I feel like if I had grown up to be an amazing farmer, I may have earned their respect. I’m a little unknowable to them. My mother said [my first book] was an awful book, but then everyone got over it.

The writing side of you becomes parts of your personality that the family eventually come to accept. “She collects tropical fish and writes books.”

Yeah, my dad keeps waiting for me to grow up and get a real job.

They’re still in Africa, alive and well?

In Zambia, yes. Mom has malaria.

Oh, again? When are you going back to Africa next?

In a month. I guess if there is anywhere in the world where I don’t have to explain myself, it would be there.