In the sixth century BCE in what is now India, an ascetic movement was underway. The relatively new agrarian economy, writes Karen Armstrong in her new book Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence, was made possible only by systemic violence that forced labourers to hand over their surplus grain. The dominant religious culture fêted this violence, and a movement arose to challenge the status quo. The samnyasin, or “renouncers,” dropped out of society to meditate and do yoga in the forest. Some then returned to the cities to lecture on giving up greed, hatred, and ego, acting as “social and religious irritants.”

Some of us still find yoga irritating, though today it’s for slightly different reasons. In certain circles, yoga in the West has become shorthand for narcissism. The emphasis on “self-care” in contemporary Western discourse breezes uneasily close to self-absorption, and it doesn’t help that yoga is seen as the pastime of the affluent. In the US, yoga is a $6 billion dollar industry. (You wouldn’t believe how attuned to the universe a simple Halfmoon Zafu Meditation cushion—Brushstroke in Aubergine—can make you feel for only $80.) When the first yoga studio opens up in a previously low-income neighbourhood, the cupcakes shops are not far behind.

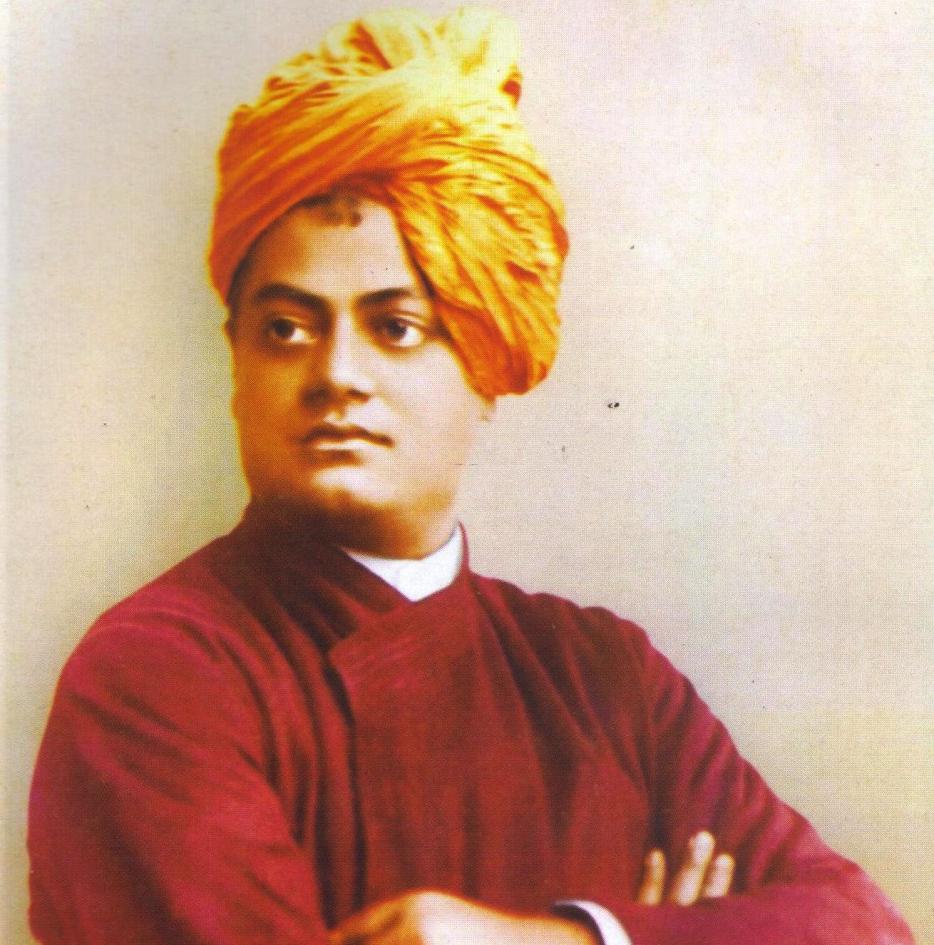

Yoga first came to mass North American attention in 1893 when Narendra Nath Datta, better known as Swami Vivekananda, gave a lecture on the principles of spiritual yogic practice at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. Yoga is an umbrella term for a diverse set of ideas and activities in India (it pre-existed the movement Armstrong writes about, although the samnyasin made influential changes to its metaphorical language). But hatha yoga—the one where you stand on your head and try to wrap your leg around your neck and so on—is what started to catch on in the US.

In the 1920s, a man from Iowa (his real name was Perry Baker, but you can call him Pierre Bernard or, as he later referred to himself, The Great Oom) set up a country club/yoga retreat outside of New York where he held yoga classes and preached about the spiritual benefits of Tantric sex. The mixture of an exoticized spiritual asceticism with an exoticized “Oriental” sensuality attracted wealthy adherents from the early years of the 20th century into the ’60s and ’70s. When yoga went mainstream in the West, it was reassimilated as a stress relief technique for the busy 21st century.

If it took thousands of years for yoga to travel to the West, it has taken only a few decades for yoga to make the trip back to India. And like most travellers, it has returned home changed. In recent years the practice of American-style yoga has come into vogue with the Indian middle class. While hatha yoga never disappeared from Indian society, the how and why of its new popularity reflects a shift toward the consumer culture associated with yoga in the West.

In a 2012 article on yoga in the contemporary Indian “consumptionscape,” marketing scholars Søren Askegaard from Denmark and Giana Eckhardt from the US analyze the re-uptake of yoga in middle-class Indian society. Residents of Chennai and Hyderabad who had taken up yoga within the past five years answered a series of questions about what drew them to the practice. The researchers found that the new, Westernized yoga was often scrubbed of its traditional spiritual aspect, and was now “easier” and “more fun,” as well as an indication of high social status. “It is now becoming like a designer stamp to be doing yoga,” one woman said. Its association with the West makes it glamorous. However, the irony of a popular, Westernized version of an indigenous practice was not lost on the people Askegaard and Eckhardt interviewed. A 28-year-old who worked as a celebrity yoga trainer said:

So what has happened now is that when the Westerners – the superior people, the great people, who made slaves of us for two hundred years, who ripped our backs apart, who ravaged our country – the superior people, when they accepted yoga as a means of physical fitness, we are accepting yoga as a means of physical fitness...THAT inferiority complex is again taking us back to our thing [yoga] . . . which is OURS! This is the state of mind of people. I’m very sad, I’m very sad.

In fact, in recent years yoga has also become implicated in a backlash against Western values. Yoga televangelist Swami Ramdev’s popular daily show has been running since 2003, and his addresses to the nation include lectures on how yoga can supplant pharmaceuticals; apparently yoga can make your teeth grow back, turn your hair from grey to black, and cure AIDS. Ascetic practice has been a cornerstone of Indian nationalism since Gandhi, and Ramdev’s message promotes the Gandhian ideal that fitness is next to godliness, as McMaster professor Chandrima Chakraborty wrote in a 2007 article. However, Chakraborty writes, Ramdev has troubling affiliations with the right-wing Hindutva movement, which insists that Hindu culture and Hindi language are the most authentic and shared expressions of what it is to be Indian.

While Ramdev’s yogic practice may comprise a rejection of the West, Westerners will find one aspect of Ramdev’s yoga familiar—it seems to be tailored for the affluent. Chakraborty writes, “For the starving masses tormented by hunger, the prescription to regularly drink milk and eat fresh fruit and vegetables or fast once a week is both ludicrous and undeniably cruel. Evidently, the poor have no place in Ramdev’s health programme.” Baba Ramdev’s enterprise is worth around $250 million; he recently bought an island off the coast of Scotland.

It’s tempting to see an association between yoga and the rich, both in the West and in the East, as proof of the modern corruption of an old tradition. But it’s worth asking why we are surprised that yoga culture should be attractive to the wealthy. Asceticism largely appeals to people only when they have a choice. The Buddha was a prince, and early followers of his ascetic lifestyle were equally well-heeled. In Christian and Jewish culture as well, the documents left behind by early ascetic communities suggest that they were composed mainly of highly educated and comparatively wealthy believers. Voluntary simplicity is just that—voluntary. Eating bread and water when you can afford better is called asceticism; when you can’t, it’s just called starving.