I go to Sara Peters’s apartment on a September afternoon, carrying pastries. I’ve probably been to their apartment a hundred times, passing the bicycles in the entrance and walking up the steep staircase to see their cats peeking curiously around walls. Predictably, the fluffy one runs upstairs to his hideout behind a bookshelf.

On one wall of their living room is a map of Cape George. On another is an oil painting by Jessica Mensch called Santa Banshee. It is part of a series Mensch painted called The Fuzz, in which different figures wander through surreal black and white theatrical sets of paper trees and warped checkerboard backdrops. The painting depicts a Santa figure on an exercise bike, in what looks like a black and white paper diorama of a living room with a Christmas tree. Santa’s face, framed by a blond wig, is in shadows, but a cigarette ember glows evocatively. The more you look at this painting, the more you are mesmerized. Both

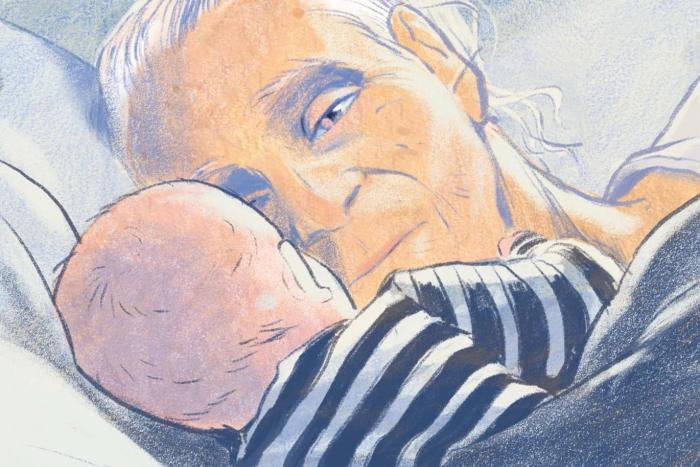

Mother of God follows its protagonist, Marlene, on a journey home to small-town Nova Scotia, only to find her mother, Darlene, is missing. Marlene works as an online psychic but her actual psychic capacity is limited to visions of her mother. The relationship between mother and daughter—depicted with layered acuity and fraught with shame, disgust, love, desire, betrayal, veneration, and rage—is the burning centre of the novel. We find Marlene at 37 piecing together fragments of herself and her childhood memories in an atmosphere charged with violence, supernatural unknowns, and Catholic metaphysics, while trying to find her missing mother.

Over the years, our conversations have spanned poltergeists, sex, childhood, our mothers, food, books, and writing,

It is immediately awkward when I turn on the recorder. The sudden premise of an interview cuts into our deep familiarity.

The following is an abridged version of the conversations we had.

Larissa Diakiw: Were you a big reader in your childhood?

Sara Peters: Yes, I was. But I can’t really remember much of what I read.

Do you remember why you read?

To recite a series of tired cliches, which are nonetheless very true to me: I read for escape and solitude and access to different worlds and to find people or experiences that mirrored my own in different ways. I read very performatively as a kid. I remember being eight and going to the library specifically with the purpose of finding the biggest, most difficult-looking books. It didn’t matter what the fuck they were, as long as they were very big and arcane, because at the time I was being bullied constantly for the way I spoke, the way I acted, and probably the way I smelled. I felt this urge to double down by consciously making myself more of a target. I was given this little stuffed mouse with glasses. She was holding a book and the title of the book was,

When did you start to understand yourself as a writer?

I started writing when I was 4 or 5, but I definitely would not have thought of myself as a writer then and honestly still struggle with that term. It feels at once unnervingly capacious and limiting—I am daunted. I’m so much more comfortable talking about myself as a reader. I usually just want to make long, unsolicited lists of books I’ve read to press upon people.

You quote a lot of writers in the notes section of this book.

I feel very conscious of what a product I am of my influences. I mean, everyone is. It feels crucial and relieving to celebrate that openly. When I got the advanced reader’s copy of the book, my favourite thing to read was the notes section because I loved recalling all the works of art that have shaped me in different ways.

I wanted you to talk a bit about your love of Frank Bidart, whom you quote. When did you discover him? When did you start reading him?

He guest taught a class I was in during my MFA, just one class at Boston University. I had heard of him, but I did not know his work at all. He was a very gentle and low-key classroom presence in a way that completely belied his profound genius. I only started reading him seriously in 2009. The first book of his I read was Watching the Spring Festival. I had never read a contemporary writer who is willing to enter what I felt he was willing to enter. And who wanted to exist at the absolute terrified, bleeding edge of everything he wrote about, who seemed to be willing to enter the unfathomable with ease. I mean, who can say, I don’t know what his writing process is like, but I’m completely obsessed with him as a writer. I think he’s one of the greatest living writers and I can’t imagine how anything I have written or want to write now could exist without him, without having read him.

Do you remember what it was like to write Mother of God? What did it feel like?

Incredibly granular and associative. I was pursuing random heat and flickers and tendrils. I never had any idea what would reveal itself or how things would congeal. That was in the first draft stage, but it always feels like the first draft to me because I write and edit at the same time.

I don’t have formalized ways of working—it’s always this shapeless, intermittently abject scrambling for the word that will pry open one chamber, then another, and another, if I’m fortunate.

The crucial narrative in the novel is this relationship between mother and daughter. Why did you choose to write about an only child with a single mother?

I wanted an uncluttered highway between them, I wanted all of Marlene’s love and rage and need for connection and protection to fall on one person, and for Darlene to have to bear that, along with her own pai

There’s incredible nuance in how you articulate shame in this novel. When Marlene is waiting for the school bus as a child, there’s this vivid mixture of class shame, outsider shame, and familial shame. And when shame turns into denial, it all felt very realistic to me. I think you rendered it so well. Can you talk about exploring shame as a theme?

When I think about that bus stop scene with Marlene, it makes me think about how, for her, shame and anger are entwined, as they are for so many people, myself included. The flare and force of anger can provide really comprehensive coverage for shame. I wanted to depict the anguished duality of shame: Marlene adores her mother and her mother’s less conventional modes of self-expression and adornment, but in the eyes of strangers or under a social gaze, her affection and idealization of her mother collapses. Even if she doesn’t believe the cruel gaze of the other, even if she thinks they’re wrong, she still has a social consciousness that makes it impossible for her to sustain her love and reverence for her mother and function as a conventional teenage girl. She has to disavow and express disgust for Darlene, then feel the resulting horror, sadness, and betrayal, because she is betraying her mother, herself, and her sense of what is real and what matters in people and in life.

When you write, “I’m slowly crawling into my mother’s face. I begin at her mouth, in between bites, and I roll away from her metal-packed molars,” Marlene is imagining going inside of her mother, very explicitly through the mouth. What drew you to this idea of identities merging? Does she want to be inside her mother, be her mother, or have her mother be inside her?

All of those things coexist with her desire to be known by her mother, and to be believed by her. If Marlene can inhabit her fully, her mother can inhabit her fully, and they can be entirely known to each other. One of the notes in the book is the Frank Bidart line, “once you reach what is inside, it is outside.” That section of the poem is about trying to reach the very core of something, but once you reach it, finding yourself existing only on another exterior. I was so struck by the idea that you can never actually be fully inside something; you just meet another wall. So that, and Marlene existing under some delusion that she could find in her mother the entire world, everything she needed, every form of sustenance, something always renewable.

In Mother of God, the reader is rooted in the material world, a world of objects, but there’s also a supernatural otherworld. So we’re vacillating between this very physical world and then this world we don’t quite understand.

I wanted the book to exist on a third plane where it felt partly myth and partly real because I’m broadly uninterested in realist writing most of the time. I don’t think there’s any such thing as realism, or I’m not interested in writing literal, straightforward depictions of things.

But I can say that I don’t want the book to be entirely pitched as ethereal or otherworldly either. I don’t want it to exist entirely on some other plane of purely surrealist writing. It felt important to have a lot of gross or sacred materiality.

Why reject straight realism?

Because I don’t believe it, it’s just not true to my experience of being in the world. So, it doesn’t feel like a choice. To me, every living moment is surreal, all the time, so it feels like a transcription of that. I can’t account for anything that has happened to me. I don’t know if things only feel real under the auspices of the restrictive definition of reality that I was handed when I was a child.

Can you talk about your interest in hauntings, ghosts and the undead? Have you always been interested in this parallel reality of ghosts or people that are lost and voiceless, or am I misinterpreting what ghosts signify to you?

No, no, you’re definitely not; “ghost” is a very expansive term. I’ve always felt haunted in every way, for as long as I can remember. I think most people feel haunted. I think it’s a near universal experience. Some people have pragmatic ideas of what that means and other people have more tilted or so-called supernatural ideas of what that means, but I think of haunting as a universal psychological experience, which can be connected to otherworldly manifestations but doesn’t have to be. It’s built on feeling and interior shifts, the sites we return to over and over again. I personally feel very overpopulated in that way.

In an interview for your previous book, I Become a Delight to My Enemies (Strange Light), you say that you intended the marginalia, moments where ghosts of the town speak, to be another aspect of a collective consciousness surfacing. Did that idea come out at all in Mother of God?

My experience of my own mind is that it’s very fractured and chaotic, constantly issuing forth random observations, commands, and invectives from different corners. I was interested in having that sense of things in the book, partly because I only have my own consciousness and that is how it feels to me. It can be really disorienting, but I wanted that to be present.

I feel eternally pulled back and forth and down and into projections, fantasies, and memories. I don’t think this is specific to me…I think our minds are largely non-linear. And one of the oft-cited symptoms of living with certain types of trauma can be unbidden, intrusive thoughts. I wanted to show that in the book, and I wanted to “show”—if you can forgive me the clumsy word—dissociation. I wanted to write from as deep inside someone as I could manage. But I think that is always my intention. To press inward for as long, as far as I can.

Another quote that I loved was, “Isn’t every living moment an act of ventriloquism?” Can you talk about that at all?

All I can think of is what I’m doing right now, the immense falseness of sitting here trying to push intelligent answers through my face in words that string together and make sense, while grappling with my extremely unwieldy interior.

Wait, I’m curious how you feel about interviews.

I mean, I love reading them.

How do you feel about being interviewed?

I’m grateful that someone is interested enough to want to interview me, but I hate doing interviews. I don’t think I’m very good at talking about my writing. I feel like everything I say, everything I assert, contains its total opposite in my mind. So, I find myself struggling to say anything of substance at all most of the time.

When things are contradictory, it’s an unpleasant experience internally, because usually only one of them is expressed. You choose the one that you feel is most adequate for the moment and it’s just so partial and meagre.

What are you reading right now?

I’m rereading Encampment by Maggie Helwig. It’s an incredible book, which I think everyone in Toronto should read. It is enormously politically important. I was telling you recently that I’m also reading Paradise Lost. I’ve been thinking a lot, too, about a book I want to reread, The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schwarz-Bart, which I read years ago; something in it is beckoning me right now. I don’t know why. And I finished Our Evenings by Alan Hollinghurst the other night, which was good.

I wanted to talk about Nathalie Léger, Barbara Loden and her film Wanda since we’re going to see Wanda tonight.

What did you think of [Nathalie Léger’s

I love that book. You gave me a copy but I’d already been obsessed with it; I had been getting it out of the library over and over again. I like the way that Léger uses Barbara Loden to explore her own relationship to her mother, even though I think they had extremely different lives. There’s this idea of recognition. I like the way Léger moves around a topic and explores it in different ways. What made you think to give it to me?

I like her sentences.

She’s a good writer.

Do you want to eat that last piece?

No, you go ahead.