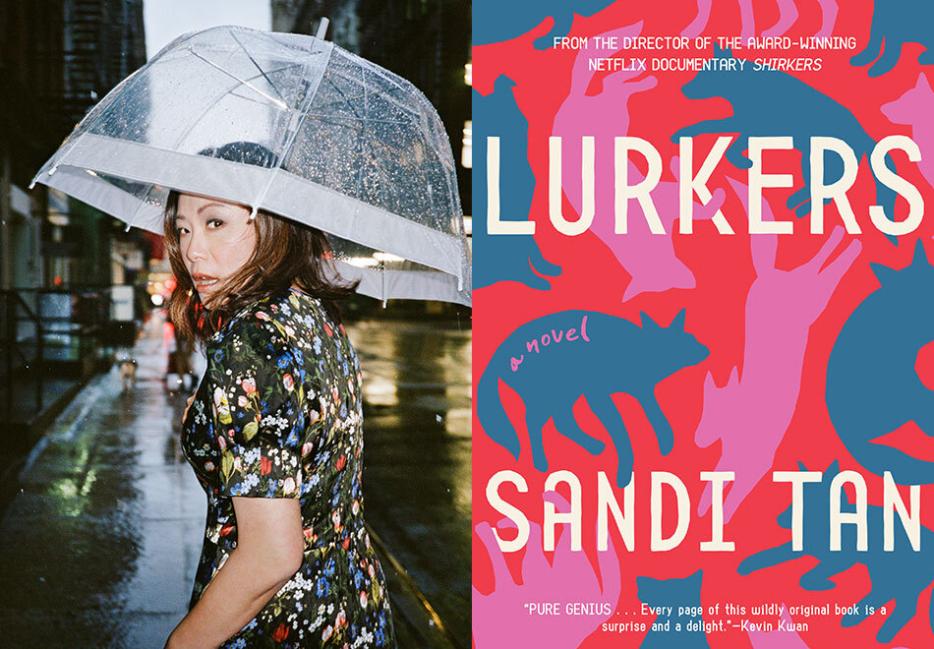

I’ll use the same word to describe Sandi Tan’s titles that she uses to describe LA: slippery. When Sandi says Shirkers, it could mean two things: the technicolour road movie she made with her friends as teenagers in ’90s Singapore, which was then stolen, or the subsequent award-winning documentary she made about the experience.

Following up this documentary is Tan’s newest novel with the phonetically twinned title Lurkers (Soho Press). To shirk is to avoid—a slinky shoulder movement, a getting out of something. Lurking implies mystery, roaming around a fixed point—the opposite of getting out of something. When asked, Tan says the projects aren’t meant to be tied by their names, but the shared motif is indicative of her approach to storytelling. Both lurking and shirking are verbs that forfeit attention—Tan is interested in feeling slightly on the outside, wondering where the main action is.

Lurkers shifts kaleidoscopically between the residents of Santa Claus Lane, a street which, because of how often the suburbs of LA appear in our media, elicits a twinge of déja vu. This narrative rotation allows the reader to see all characters from all vantage points—like peering out of an open window onto the street, blessed with total omniscience.

The last words of the novel’s epigraph are, “Running to the extremes.” The novel, perhaps a demonstration of this phrase, follows Rose and Mira, teenage sisters who dodge grief, plot ways to convince their mother not to move their family to Korea, and navigate a lusty coming of age. Down the street from them is Raymond, an aging supernatural pulp novelist, holed up in his fantasy of gothic romance with plenty of whiskey. Then there is lone ranger Mary Sue, her adopted daughter Kate, and a smattering of surrounding neighbours occasionally getting in on the tangle. The residents of Santa Claus Lane exist on the outskirts of each other's lives, lurking in the background. Each of them running to their own extremes is what brings them in contact with one another.

I spoke with Sandi about genre flicks, the collective cultural consciousness transposed onto certain neighbourhoods, and the novel as a great teenage excuse.

Emma Olivia Cohen: There’s an anecdote I’ve heard you tell about growing up in Singapore. You’d see the posters for new movies months in advance of being able to actually see the movie. Usually when you finally did see the movie, you’d be disappointed, because in the interim you’d been projecting an idea of what the film would be like using the material from the poster. And what you’d subconsciously created would be more weird, stunning, interesting than the movie itself.

Sandi Tan: Yeah, doing this would give a talismanic effect to the movies. Growing up in Singapore, I was so far away from the centre of things that I actually had a lot of space to dream. No one was policing my creative thoughts because they were policing everything else; you have a lot of freedom to imagine your way into things. Some of the most subversive and interesting minds I know are people who grew up in Singapore and were unsupervised as teenagers, keeping up our grades so no one would bug us. The internet takes away a lot of that magical dreaming, because there’s no waiting time. You never have to imagine what things are going to be like. I was forced to imagine things a lot more, and it became a muscle I applied to everything else.

Does that dreaming muscle come in handy for writing?

Yes. I would have thought experiments all the time. I imagine everyone does—a drawer full of unfinished thought experiments. Imagining my way into various characters as a writer is the same muscle, you’ve identified it correctly. It might be unfair, though, my being disappointed in the movies, because I’d be watching them on pirated VHS tapes I’d go through great trouble to procure from Malaysia. Mostly what was available were horror movies, or movies with a lot of sex and gore. That’s what was popular—those Cannibal Holocaust movies were huge in Malaysia. But sometimes you’d get something like Mystery Train by Jim Jarmusch, which had no way of getting a proper release in Singapore. The pirated VHSes would have been filmed at the opening weekend in LA or something, and you’d see silhouettes of heads of people getting to their seats, you’d hear their laughter. This was the eighties when the worst movies were being made in Hollywood, but they became very magical to me because they were so unattainable. They had a strange distant power. So these very mediocre movies about teenage hijinks in some imaginary America became slightly totemic for me.

There are whispers of different genres in Lurkers. There’s the supernatural poltergeist, the spectre of helicopters surveying the neighbourhood for crime, a mystery motif with a reappearing anonymous girl in the window. Do you find these invocations of genre interesting for opening up different possibilities of storytelling?

I started writing this book a long time ago now, when I was moving into a suburban neighbourhood in North Pasadena, adjacent to Altadena, an unincorporated part of LA. The houses and the streets were so familiar to me—I’d seen them many many times before. Not in my dreams, but on TV and in the movies. People shot a lot of TV and movies in the suburbs of LA in the ’70s and ’80s, and even later too, standing in for the suburbs that could be “Anywhere USA.” So when I moved into that neighbourhood it was like all the genres, TV shows, movies started bubbling up. I could see various kinds of stories playing out from those pasts that the neighbourhood had experienced in a fictional form on the screen. The stories that make up the book began organically because I could see the landscape as the palimpsest of all kinds of stories that had already been told.

It’s like a collective cultural consciousness mapped on to the physical neighbourhoods. I was trying to identify, when I began reading, who the main voice of the book was going to be. But it really oscillates completely between so many vantage points which all have their own narrative arc. It has that familiar feeling of walking down a street and wondering about all the lives contained in the houses, but then also the satisfaction of letting us fulfill that fantasy. A Vertigo vibe.

I was looking around at people in the neighbourhood I live and feeling like a lurker myself, feeling like I wanted to know them. And the easiest way to do that for me is to imagine my way into their heads. It forced me to become acquainted with an unlovable neighbourhood. These suburbs aren’t immediately likeable and knowable. There’s something very slippery about LA. It’s built with fantasy in mind, both in its various architectural styles—the different fantasies of different developers—and because the people who move here are all fantasists hoping to escape something. This constant going towards something makes it confusing, interesting, hard to pin down.

It’s interesting what you say about going to LA to find a fantasy, because a lot of the characters in Lurkers feel confined in one way or another by their circumstance as well. Does that feeling of confinement contribute to an imagination, or a lack of imagination?

Everybody in LA hides in their homes. Maybe because there’s more space or people are moving in and out so quickly. People think that people in LA don’t buy or read books, but I’ve heard that they’re some of the biggest book buyers in the US because they have space to put them. Everybody consumes their media and dreams in their own private fiefdom. There’s less of a chance of running into your friend in the street. So a lot of people tend to look inwards.

At one point the character Mary Sue is talking about the concept of the nuclear family, and she describes it as a process of trial and error. She says though her own family had the opportunity to succeed, they failed at the experiment. I was thinking it could be said maybe all of the families in this book fail at the experiment of the nuclear family. Does this failing open up room for new ideas around family and connection?

This is something I do feel and believe, perhaps due to my own funny family circumstances. The strongest family bonds I’ve felt or witnessed were often with people who chose their families, or adopted their kids, or were substitute parents, foster parents, aunts and uncles standing in. I like playing with the feeling of choice versus what you were born into. It applies to the choosing of neighbourhoods, or migrating to different places. Human beings have much more propensity for choice and have more control over their lives than they might feel they have. The characters in my book are constantly searching for not just family but also home, and it’s often not where they thought it was going to be. I like the idea of being surprised by life and embracing it, and not just feeling shortchanged by your unhappy family situation.

You’re adapting the novel The Idiot by Elif Batuman into a film. One of the major themes in The Idiot is this idea of falling out of narrative, and I feel like a lot of the characters in Lurkers have this ghost life or parallel life that lives alongside them. Kate almost died in a plane crash as a child on her way from Vietnam to America to be adopted, Rose and Mira the teenage sisters are threatened by their mother that they might be moving to Korea at any moment, Raymond lives largely in a fantasy life—I wonder if these two ideas correlate to you, falling out of narrative, and then having this parallel potential life you could have had?

I like the idea of falling out of narrative. For the longest time I was trying to figure out my life, and making the film Shirkers and making sense of it with a narrative really freed me. I feel like I didn’t get to finish my growing up, didn’t stop being a teenager until I completed the film, way too many years later. And it’s valuable, making sense of your life. I didn’t think of the characters in Lurkers as being that way, as narrativizing their own lives, but I think when they do, maybe they’ll feel free or something. Or more fulfilled. We all have these things coming back from the past, things we did or didn't do, and you have to choose which path you want to take. I felt as a teenager when I was making Shirkers that I wanted to choose the path that would make a better story. I knew I had the choice of doing something that was tame and boring, or something that was interesting potentially. And I was always after the better story, and that was the thing that kept me sane as a kid with relatives or mentor figures who were less than kind. If I could joke about it and make a story about it, that’s the way I could tame it.

There are two teenage pairs in the novel, Kate and Bluto, and Rose and Arik. You write, “being teenagers provided the perfect alibi for their extreme disaffection.” What about teenagehood as a container or excuse is interesting to you?

Being a teenager is an alibi for everything. You can do anything and blame it on your being a teenager. It’s just the best. And I think that’s why people try to hang on to it as long as possible. It’s because teenagers can get away with everything—you can blame stupidity on being a teenager, and if you say something bright or charming or smart then you’re precocious. Too many people find that too special a time, and in many ways every single character in the book is an overgrown or misplaced teenager—even Mary-Sue, whose coming-of-age, she feels, arrives in her sixties.

I loved the character Raymond. He’s an aging supernatural pulp novelist. He has this imagined fantasy life, which then he writes into books, and the books bring him the money which allows him to have the aesthetic luxe backdrop to the life he wants. But the life he actually wants, which is this dark gothic romance and adventure, doesn't come with the background. He’s essentially set dressing for the life he wants. And then it’s sad, because it doesn't come. I think this is something that’s relevant culturally; we’re all becoming more aware of how to set dress for the life that we want.

I know people who are like that exactly, who think they want those exciting things but are actually quite scared really, and want to be living in comfort and are very happy with things around them. There is a famous author I knew that certain details of Raymond’s material life come from—like that the walls of his library are filled with his own books in various languages. And that his entire home is extremely well art directed, like an edifice to himself, slightly tomb-like. But also perfectly art directed in a classic Hollywood-’40s-film-noir way. Like that famous author, I imagine that somebody like Raymond is afraid of the actual world out there, and that’s more frightening than anything he could write about.

I’ve heard you talk about the formal structure of movies like Mauvais Sang, where the plot concept allows playful or bizarre sequences to exist within the film because they don’t have to move the plot forward. Are there any sequences or ideas in Lurkers that you wanted to include that were playful and fun, but not necessarily serving something grandiose?

Yeah, I think I have all these silly bits. That’s the nice thing about writing a novel—you can throw in a lot of things you think are just fun to write about. Whether it’s the swamps of Florida or the numerous churches that line the freeways in LA. Kate’s experience in Vietnam, the dying city centre of Des Moines, Iowa. Impressionistic sketches of different landscapes. I wanted to collect all kinds of places I’ve been to and noticed things about, and imagine them into the pasts of the various characters and see how they would form them. It makes life less lonesome, you know? Writing novels is my cowardly way of being an extended teenager, because it gives me an excuse for trying to make sense of everything that’s haunted, confused and delighted me. I am more like Raymond than most might think.