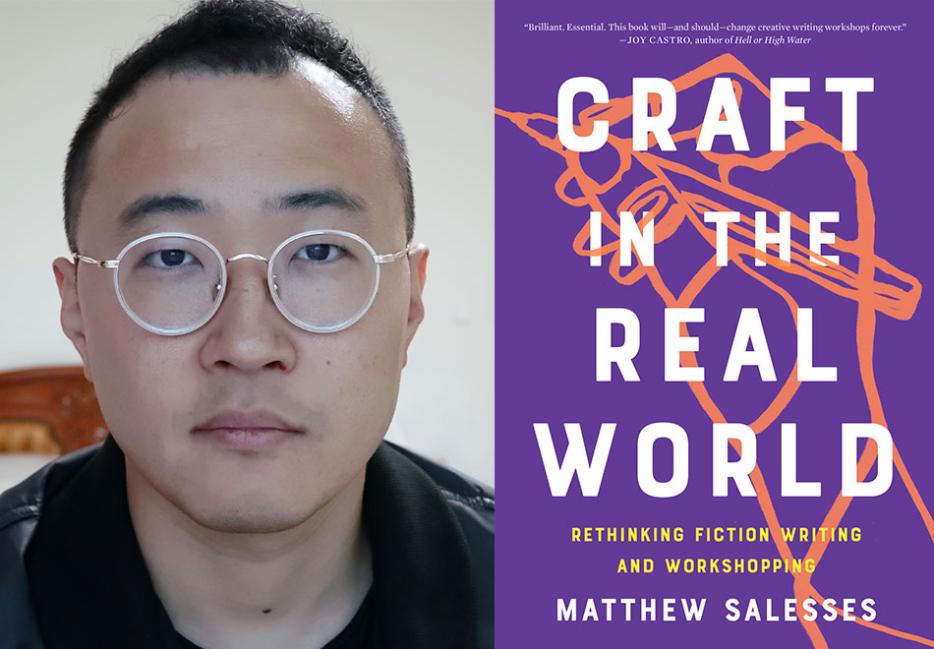

“This book is a challenge to accepted models of craft and workshop,” is how Matthew Salesses opens the preface to his latest book, Craft in the Real World (Catapult). “The challenge is this: to take craft out of some imaginary vacuum . . . and return it to its cultural and historical context.”

For those who teach and are trained in traditional fiction MFA programs, the book might indeed feel like something of a shot across the bow. The first essay, entitled “Pure Craft is a Lie,” takes aim at certain workshop truisms that, in Salesses’s estimation, are less about objective literary merit than they are about reinforcing white European cultural hegemony.

He gives the example of dialogue tags: writers are usually encouraged to mark their characters’ utterances with “he said” or “she said” rather than any other verb, because “said” fades into the background, while other verbs call too much attention to themselves. But, Salesses argues, that’s just because we’ve been trained to read “said” as a background word; another culture might use another term and see it just as neutrally. To tell a student that “said” is her only option is “not to teach her to write better, but to teach her whose writing is better,” Salesses argues.

Salesses doesn’t just debunk; he also offers constructive, inclusive suggestions for rethinking and remaking workshop, drawn from his experiences as both a student and teacher in MFA programs. (Salesses holds an MFA in Fiction from Emerson College as well as a Ph.D. in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Houston; he is currently an Assistant Professor of English at Coe College.) The second half of the book, entitled “Workshop in the Real World,” includes suggestions for alternative workshop models, a sample syllabus, and a collection of writing exercises intended to help professors start to detangle their understanding of the craft of writing from our cultural expectations of what a story ought to be.

Salesses and I spoke by phone on Wednesday, January 6, 2021, the day that a mob of violent insurrectionists stormed the U.S. Capitol Building to protest election results. It was impossible not to be thinking about the fact that the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, perhaps the most famous MFA program in America, became what it is today in large part because its then-director, Paul Engle, solicited donations from conservative businessmen with the promise that the writing the workshop produced would fight communism. Storytelling has always been and will always be a politically freighted act; I was grateful to talk to someone who’s thinking deeply about how to do it carefully on such a difficult day.

Zan Romanoff: We've come to think that, if you want to be a writer, you will also teach, because that's how you make money. But as vocations, they're really not the same thing. When you pursued higher education as a writer, at what point were you like, I actually also want to keep teaching?

Matthew Salesses: Before I did my MFA, I taught English to students of all ages. I found that I really liked teaching; my parents were both teachers, and as a kid I thought, “This is never what I'm going to do! I'm going to do the exact opposite of this!” But once I got in there, it felt really great to have that interaction all the time.

Also, I [was able to] get perspectives from people I never would have gotten perspectives from otherwise. Especially in an ESL context, they're just wanting to speak, and so they're sharing whatever's personal to them. Listening to all these different people's stories was like reading a short story anthology.

I felt like I knew how to teach ESL really well—I'd gone through training and been certified in it, and had very good results as a teacher. But then I got in the classroom, and I was doing the same things that I had been taught to do, but I could see that it was not nearly as good as I'd thought it might be. I felt immediately like, it could be so much better than this, and I didn't know how, because there was no training.

In creative writing pedagogy, there's this idea that creative writing training has mostly been lore-based—we hear from other people what they do, but there's no written record or training or guide. So, I'd done the same things I'd seen in the classroom. The only resource I could go to was to ask more people, so I spent a whole AWP (Association of Writers and Writing Programs Conference) just asking basically anybody I knew—and the good thing about AWP is that everybody you know is in one place—how they ran their workshops.

Like you would expect, 80 percent of them said the exact same thing. But then I ran into [writer and Northwestern University Artist-in-Residence] Nami Mun, and she said, "I do every workshop differently, of course." It just really blew apart everything that I'd thought about teaching in a workshop style, which was mostly, you take the story and you fit it into the machine that the workshop is, and what comes out at the end is—I don't know what comes out at the end, really.

I started experimenting right after that, doing workshops differently for maybe half the class, trying to think about, rather than the kind of regular model that I'd learned, which stories might benefit more from people just talking about things? The thing that I hated, as a student, about workshops was when we spent five or ten minutes talking about something that the author could have just spoken up and said, “This is a cat, not an imaginary being.” [Many MFA workshops operate under the so-called “gag rule,” which stipulates that the work’s author must be silent for the bulk of the classroom discussion.] And so, instead of having those conversations, I started asking the authors, “Can you just tell us what you were trying to do here?” And it worked so much better. We had more time to talk about other things.

Then I started doing things that I did during revisions. I was just troubleshooting things that I found not that helpful about the workshop, which is that you've got this sometimes great, sometimes terrible advice, and you go home and you're like, well, now I have all this advice, but no one's actually taught me anything about how to revise the manuscript from this point. Nobody's said, “Here's what you do next.”

No one's said, “Here's how you actually apply the advice to the manuscript.”

So instead of doing the advice, which people were writing in their letters anyway, we started cutting up the manuscript and moving it around in class, and doing some of the things that people might do on their own together in a shared space.

One thing I really liked about workshop as an MFA student was, my thesis professor was [the writer] Margot Livesey, and she would do these really amazingly ... I don't want to say bad, but she wasn't an exceptional artist—they weren't really good drawings, and we got to see things, like how her mind worked visually. So, I started doing that too, and everyone would laugh at the drawings. So we'd have a good icebreaker where everybody thought, “Look at that, he's a terrible artist.” But it would actually free up a lot of different ways of thinking about the story.

So, you're teaching and you're experimenting with all of this stuff—at what point do you start to think, “This should be a book?”

That didn't happen until much later. I'd been writing a bunch of the Pleiades blogs about craft, and I'd written a bunch of op-eds around the internet, for NPR Code Switch and places, about the workshop. I had so much material. I'm always thinking, “This should probably be useful in some way.” I'm very much a product of productivity culture, so I started thinking, “This has to be a book at some point, because otherwise it's just wasted material.”

And then [the writer] Roxane Gay tweeted something about how it should be a book, and a few editors contacted me, and I sent these links to my agent and was like, hint hint! So, we wrote a book proposal and went out with it.

And then what was it like to pull all of that material together? Were you surprised by how much you had, or did you feel like you had a lot of gaps to fill in?

It was more the latter. I had way too much material, but a lot of it was about revision. I wrote about revision for a long time, and I wanted the book to be more focused on what craft is, and where it comes from, and how we can use it to better serve marginalized writers.

I also found because I had written these things for different venues and different editors—and the blog posts were blog posts, they were very much in blog post voice—so a large part of it was, how do I make all of this writing for various audiences into a cohesive argument for a specific group of people?

I couldn't do it completely—that's why I separated it into two halves, because I felt like there were two separate but related audiences. There was the part that was really teaching-related, and you could use that in the classroom, and then a part for both those people and people who just wanted to write on their own.

That's actually something you talk about in the book: how important it is, as a writer, to define your reader to yourself, to understand who exactly you're trying to reach. So, I'm curious who the audience is for this book, beyond, of course, MFA instructors?

I'm always writing specifically for my friend Kirsten Chen, who's also a writer. She's also Asian-American, but she grew up in Singapore, and so she has a slightly different background—she came over in high school. So, there's certain things I have to tell her more about to give her the context that you might have gotten just from growing up in America. There’s a certain amount that I have to fill her in on, but I think that's a good amount of filling in, that could be done for anybody who doesn't have exactly the same background or interests.

After that, I was thinking of friends of mine who are teaching right now, writers of colour who are teaching, trying to find something that they could use in the classroom. Some of the pieces just came out of people asking, do you know any craft essays by a writer of colour on this, and me going, “No, I don't know anything—maybe I should write one?”

Some of this stuff came out of talking to students of colour in MFA programs who would run into difficulties trying to make their experience feel important to their professors and the administration and having nothing to point to. It's hard to do that, even though it should be easy, just by your own experience. It's hard to do it unless you have something to break in and say, “Look, we can use this as a resource.” And so, I really wanted it to be able to do that for students in those programs, or in any workshop setting.

And then of course it's the editor's job to say, “Let's broaden this to everyone!”

And, of course, this is my bias, because all I do is write, and think about writing and talk about writing, but I think everyone who reads fiction should want to understand how it gets made. I loved that this book articulated some things I felt were missing in my own reading practice, in terms of reading mostly fiction by American authors and not understanding much about other narrative traditions.

I felt like when I was writing the book, partly what I was doing was taking the stuff that literary theorists have been talking about since the ‘80s in America, and before that in Europe, and just moving it to a writer's perspective. That felt strange, too, because you could find those books out there if you were just looking in a different place. Most readers of regular fiction are not necessarily going out there looking for post-structuralist theory or something.

Right, and this felt like an approachable way to start having that conversation around how what we think of as right or wrong, good or bad, in terms of storytelling is actually a culturally constructed standard.

Something you mentioned earlier was that you write a lot about revision, and that makes a lot of sense to me, because one of the things you write in the book is that a first draft is often your first instinct, and those instincts are often not the most original thought you could have, so you have to drill down further to find out what you actually think or want to say.

Can you talk more about why you feel like revision is such an important part of the process? I feel like that's something that I, as a beginning writer, did not understand at all: how much something could change in the revision process, and maybe should change.

What we learn as revision is more like editing things to be more presentable, and less the kind of revision that fiction writers do all the time. But that was the education I had, too, so when I got to it, I just knew, what I'm writing is crap, I really don't want it to be crap, so I had to [do] something! So, I'd just work on a story endlessly, making the little edits, until I could figure out more macro changes.

I believe really strongly in revision. I used to make my students take an implicit bias test at the beginning of a course and I would get the same result: we all had implicit bias, obviously. My students would say, “I'm not racist, I'm not sexist,” or whatever. And I would say, “Well, that's because you're able to think about it. You don't always act on your first impulses. We have a mind, and we can use it to correct our behavior and do better and become better people.”

To me, that's revision. You put on the page all of this really deeply culturally informed subconscious stuff, and you have to use revision to be able to think about why it's there and what it means. And not just what it means on the page, but what it means that you're writing that thing in the world that we live in.

It takes a long time and a lot of work to make these unconscious things into conscious decisions. For me the idea is, we act consciously on the page and in life, but I don't think that's a quick and easy process, trying to break your habits.

You also had a novel come out this summer, Disappear Doppelgänger Disappear. Can you talk about how you’ve applied the craft lessons from Craft in the Real World to your own fiction-writing process?

So much of [Craft in the Real World] came from teaching, and trying to teach better. But also, so much of it came from the novel.

I sold it on spec in, like, 2015. I thought it would be so much better to sell it on spec and then not have to worry about it being sold, and it wasn't better. It was just bad in a different way. So I ended up, instead of worrying about it being sold, worrying about what I was doing writing it, and it took me a long time, after it sold, to get a working draft going.

I wrote a ton; I was working on it constantly, but I couldn't figure out what I wanted it to be for when it wasn't for selling the book. And so, a lot of my thinking on craft came out of thinking, well then, what am I doing here? What is the purpose of this? In my MFA we got the whole, there is no purpose for art except art, and this was the first time I had to face the fact that that wasn't really a thing.

I really did have to spend a long time trying to figure out, one, who was I writing for—a lot of it came out of that—and then, why would they care? Unless it's just for the fun of reading a story—which is fine, it's a good purpose, it just wasn't my purpose. A lot of the book came from trying to figure out what I was doing and why I thought writing was important, and why I kept holding onto this idea that writing could do something in the world, why I was doing it and not doing something else.

One of the things I love about Craft in the Real World is that I think a lot of MFA students have gone through the process and felt like—well, that didn't work for me, and so I must be broken in some way, I’m not a real writer. And this book is you saying, no, it's not you that's broken, it's the process. Giving them permission for their experiences to be validating, instead of deflating.

I took a couple of years off after my MFA and just taught, and worked, like, a regular job, and I was so sick of it that I wanted to go back and do more, so I got my Ph.D. But when I got into my Ph.D., it seemed like an accepted thing amongst everybody that workshops were terrible and they hated them, which seems like a weird thing to do, if workshops are terrible, to do another five years of those.

I don't know if people thought it was their fault; people come to accept that it's just a thing, a crappy thing that they have to go through, like some kind of initiation process or something.

I actually really believe in the workshop process as a thing. I think there's a lot of value to it, and I also think if you're only doing workshops, that's probably not the best way to educate someone in creative writing. But I have a lot of faith in the workshop, and I think it can do a lot of interesting work.

I'd love if you could talk about how you've seen workshops evolve at the level of the institution. Obviously, you've been evolving your own methods pretty substantially, but what about your colleagues—how much interest is there at institutions?

I think you've got two camps, really. One camp that thinks, “This is just the way we do things, and this is how we're going to do things, and to do it this way is to be a real writer.” But I actually think the other camp is—it's definitely growing faster. It's the only one growing, probably, at all.

At first, when I started doing [different types of] workshops, I would get a lot of pushback to them, just because they were used to the other way, and they thought, “This is the right way.” Even though they didn't like doing it that way! They still thought it was the way they were supposed to do it.

I don't get that much anymore, but I teach mostly undergraduates now, and they've been less indoctrinated into it. But I do think still a ton of the workshops are being taught exactly the way they were taught in my MFA—gag rule, et cetera.

I think a lot of people say, “We can't let the writer talk because then they'll get super defensive.” But like, why would they get defensive? They would only get defensive if you're attacking them in some way. It doesn't have to be attacking. That's not the only mode a workshop can offer.

I wanted to ask about one of your specific phrases in the section you call “Banned From Workshop.” You ask students not to use economic language to describe stories—"this didn't feel earned," "it didn't pay off," et cetera. I realized that those are things I say all the time, and as much as I don't think stories should be economic exercises in theory, the Western story structure is very much built around the economic concepts of earning and paying off. So, I'm curious how you try to think around that conflict.

I do that because my friend, [the writer] Laura van den Berg, banned those economic terms from workshop, and I was like—I had never banned anything from workshop before, and I was like, if Laura's gonna do it, I can do it. I do think everything is so capitalistic, and it's nice to escape from that for a little while!

We talk about how something feels: "The character feels like this here, I see it building up to this emotion at this point, and yet it doesn't seem as if the character in this passage has the reaction ..." Or we talk about expectations that the author has set up. The expectations that we're setting up, that we've gotten from reading other books. The expectations from what we think the audience is and what tradition we think the novel is in, whether it's fulfilling those expectations, or trying to undermine them in some way. We talk more about our personal readerly reaction to things and more in terms of expectations.

My students don't really have a problem with it—they seem able to avoid that kind of language. What is really hard for them is avoiding the relate language: "I relate," and starting everything with "I think," or "if it were me"—things that totally center them in the process. That is really hard for them to break.

I find things relatable; it's just a funny way of speaking about things. Students seem to have it as a saying that they use, like, "relatable!" That's a thing and it's fun to say, but I don't think it gets at what's operating in the words themselves. It's not something the author can control: whether or not something is relatable to somebody. It's a totally legitimate reaction to something, [but] I don't think it's very helpful to an author at all. It's not very helpful to their craft decisions.

So obviously this has been an incredibly weird time to teach—how has it been running workshops in the pandemic?

It's very different. I think the most successful things are when I try to approach it as if it's a totally different thing from teaching in person, and the least successful is when I try to port the things I was doing in the face-to-face classroom to an online environment. The attention is different.

My students seem to have a hard time—there're some classes where they're expected to do the same amount of work as they were before the pandemic. When I was a kid, I always thought, “What do my teachers do when we leave class? They must go in the closets.” But I think sometimes teachers do that with their students too—they think they don't have other things weighing on them, but of course they do, and in some ways the pandemic has been much harder on a lot [of] my students than it has been for me. They just have so much stuff going on.

All right, before I let you go, are there any questions you wish I'd asked, stuff you haven’t gotten to talk about yet?

The exercises! No one ever asks about the exercises! I spent probably more time writing the exercises and thinking about the exercises than the other parts of the book combined. It's interesting to think about what gets focused on later, even though the exercises, I was literally putting in front of my students and asking them to do them and was revising them as the students responded to them.

I really wanted it to be a practical book. I have this whole long rant, actually, about the mystical writer, the person who comes in and is like, “You just figure it out, you know when it's done because you feel it.” I had so many famous writers who'd visit and say nothing that was in any way substantial, and I thought, “They're getting paid so much money for this, it's ridiculous.”

One of the funny things in the research is seeing how people in other countries think about characters versus how Americans think about characters, which is, “Oh, I heard a voice! A voice in the wilderness, and I just wrote down the voice that I heard.” Nobody else in the world thinks about it like that. They're like, what? These are made-up things, that you yourself are making up!