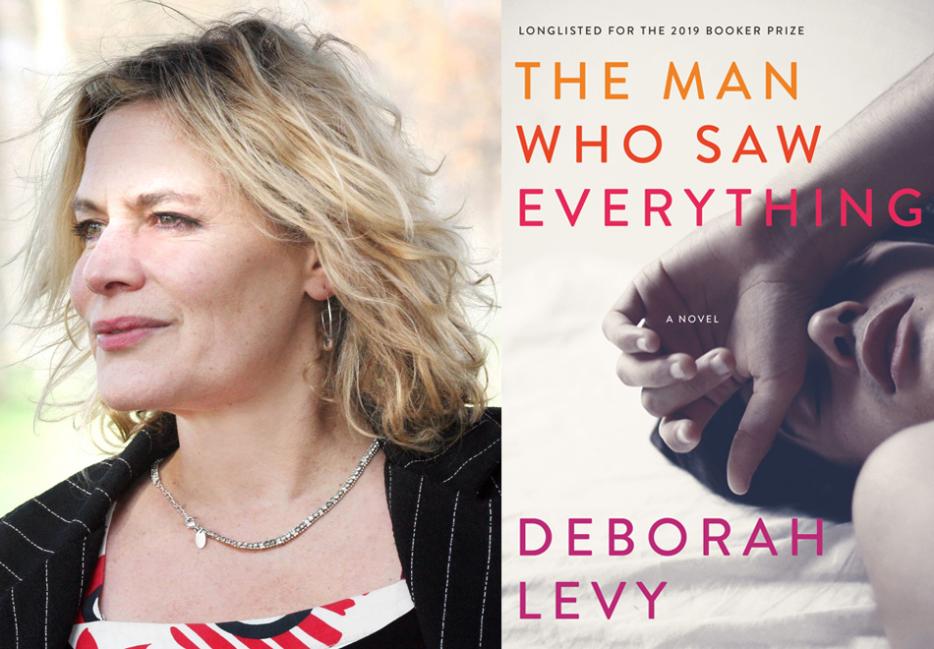

Deborah Levy knows what she is doing. The British novelist and playwright's most recent book, The Man Who Saw Everything (Hamish Hamilton), was longlisted for the Booker Prize. It's the third novel of hers to be up for the award, after 2012's Swimming Home and 2016's Hot Milk. These books join the some several dozen other novels, short story collections, memoirs, and plays that have shaped her career since the early Eighties, a constellation of work that examines the reaches of what language can do.

The Man Who Saw Everything is a tight, dense novel that opens in 1988. Saul Adler, a young, beautiful historian, is preparing a research trip to East Germany. In London, he suffers a minor accident after a car grazes him at the iconic Abbey Road crosswalk. Suffering only a few scratches, he goes over to his girlfriend's house, a photographer named Jennifer Moreau, who sleeps with him and promptly dumps him. These opening few chapters are filled with small, seemingly inconsequential details that Levy riffs on in the first half of the book, only to turn the story on its head midway as she thrusts the narrative nearly thirty years into the future, on the heels of 2016's Brexit vote, to probe what has changed, what has stayed the same, and how we misremember the past.

Levy and I meet at a cafe in Toronto's Little Italy neighbourhood on the first snowy day of the season. She is a confident but soft speaker, and her voice is often drowned out by the sound of the Backstreet Boys and Beyoncé coming from a pop radio station on blast. She is a deliberate writer, able to speak at length about every choice that appears in her novel.

Anna Fitzpatrick: How has the tour been going?

Deborah Levy: I love touring. For the Americas, I've just come back from Santa Fe, then to New York, now I'm in Toronto. Before that I was doing the British Tour. That was really something. Liverpool, we launched the book there, because there's a Liverpool theme in the book. That's where the Beatles obviously grew up. They got a choir of 35 people to sing "Penny Lane" in German and in English.

It's a book with so many cities featured prominently. You have Berlin, the two Berlins, and Cape Cod.

I do. I'm a swimmer. So, I like to swim across the ponds in Cape Cod. There's Berlin 1988, London 1988, Berlin further on, and America.

You open with a quote from Susan Sontag's On Photography. She says to photograph someone is to violate them. She's writing that in '77, but your book takes place under the surveillance of the GDR in 1988, and then in 2016 with a level of technology that brings another kind of surveillance. How does that quote work in these contexts?

So, there's Saul Adler, when the book opens he is twenty-eight. He is a freakishly beautiful man.

Described as "more a rockstar than a historian."

He's a minor historian, he always says. His girlfriend, Jennifer Moreau, is an art student, and the thing is that Saul is such a slippery man. She can't ever really possess him because everyone wants a piece of him, and he's so ambivalent about attachment anyway. The only way that she can really get hold of him is through the lens of her camera. I had written this, and then I read the Sontag quote and I thought, "Oh yeah, maybe I'm doing something right." She's talking about how it's a certain possession. It's usually women who are gazed upon and sexualized and objectified, and I flip and have it happen to Saul, and he reports back through the reader on what that's like. And then to talk about surveillance, we go to communist East Berlin, where there's quite a lot of paranoia about who is looking at who because everyone is spying on everybody else. I'm looking at the way the state looks at us in an authoritarian regime, the way Jennifer Moreau looks at Saul, the way Walter Müller—that's Saul's translater in East Berlin who he sort of falls in love with at some point—Saul says of Walter, "I think he saw everything there was to see in me, everything that was mad and bad and sad." The title should trigger all different kinds of looking, ways we look to each other.

Going to the gendered aspect of this, Jennifer Moreau forbids Saul from observing her the way she does him through photography, but she forbids him from even using language to describe her.

She does, and she says, "I don't want you to ever describe my beauty or my body, to me or to anyone else." And he says, "Why?" And she says, "You've only got old words to describe me." You'll notice that Jennifer, I never describe Jennifer in the book. You know she's got silver hair by the end, because Saul tells us, and she starts the book twenty-three, she's fifty-one by the time the book ends. We know how she smells. She likes to use ylang-ylang oil. She's the only character I've ever written who I haven't described, and whom, I hope, readers nevertheless get a sense of: her and her interior life and that purpose in life. I'm really interested in this question of how we might describe women's bodies in a way that isn't objectifying. What kind of language, new language, would we use as writers to do that? But Saul keeps his side of the bargain, and I the writer keep it with him, because he's writing in the first person. I mean, did you get a sense of Jennifer Moreau?

My idea of what she looked like changed over the course of the book, but I did picture her as a counterpart to Saul's glamorous dandyism. She wears that cap at the beginning, pulled down, and I figured her as someone with a certain chicness. But I didn't have a physical sense of her.

You sort of had an art student idea of her.

Which I liked. It's tempting, talking to you, I have this urge that I have to fight, to ask you to fill in all the ambiguities of the book, but those ambiguities make the experience of reading the book stronger. As an author writing someone from such an unreliable point of view, do you have a definitive sequence of events that you're writing against? Do you know what Jennifer Moreau looks like?

Yes, I do. Because I think if you're going to play around with time zones like I do, it actually has to be a very plotted and mapped out book. It might surprise you, but it's probably my most plotted book. One of the themes in the book is how history is told. If you think about yourself, if you tell your own personal history, and I do, we are likely to tell it in our favour. We're going to leave out quite a lot of stuff we feel we come up bad in. And then there are other people who can fill in that part of our history. That's what happens in my book. Saul gives his version of events, and Jack and other characters step in. Saul describes Jack as a minor character, but he's really not so minor in Saul's life.

It was heartbreaking to read the story from Jack's point of view.

In some ways Jack is a completely new character for me, because how do you make somebody who's really important in someone else's life embody that importance, given that the main narrator is always pushing him away? Jennifer steps in to fill in some of the missing history, so does the driver who runs him over. Writing in the first person is always a bit claustrophobic. I have to find techniques and strategies to let in other subjectivities. Open the window and let in some fresh air. It's not really that Saul is unreliable. I know what you mean, obviously. That's a phrase that's used a lot, isn't it? But he's a man that's been knocked over by a car. He's coming in and out of consciousness in various ways, no spoilers. He's got time messed up a bit in his mind, but he's not unreliable. What he can't do is, he can't feel things. As the book develops, he begins to feel, which is always painful. It's always painful to begin to feel. There's all this stuff around about how we should feel things all the time, but actually we spend quite a lot of energy in our lives trying not to feel things. It's overwhelming and uncomfortable to feel things.

There's this one part of the book where Saul's in the hospital, Jennifer Morreau's at his side. He takes her hand and places her hand under his pajamas, and he's hard, and his heart's going berserk, and he says, "I didn't know how to be the man you wanted me to be. I'm only just starting to feel things. I can't bear it." I don't want any unbelievable moral resolutions to things. I don't want any unbelievable massive changes in the human psyche that I write about. I want small changes.

I'm very interested in, what is strength and what is fragility? What's a strong character and what's a weak character. I don't super believe in that way of looking at things because on Monday, we can feel really powerful, and on Tuesday, we can feel fragile. We live, and we live with those contradictions. In the novels I write, I want characters not to be novelistic characters. I want them to also live with those sorts of complexities.

What do you view as a novelistic character?

That's a very big question. I'm going to answer it another way. In my novels, it's very possible for a character to have two contradictory thoughts at the same time. You tell me anyone you know who doesn't have those sorts of thoughts. I want to scoop all that up psychologically, because it interests me, and have that in my novels. What you won't find in my novels on the whole are grand narrators. Wise and all-seeing. No, I don't want them in my book.

There is that common misconception that history is an objective series of facts when so often it's subjective. There's a parallel you draw with photography, where you've taken an image of things as they are, but you see with Jennifer and the way she develops film in a dark room, or the way in which she displays her images, she has another way of seeing. Can you speak to that parallel?

She's captured Saul, age twenty-eight, and she calls her exhibition "A Man in Pieces." We learn that sometimes she just photographs parts of him, in fragments. He is a sort of a man in pieces. The book is also looking at masculinity, which is in pieces at this time in our century. Our history is speaking to this. I'm looking at authoritarian regimes and the rise of nationalism. None of those things are connected to any rigid ideas of masculinity. But Saul hasn't constructed himself in a very—he's not the kind of man his father wanted to be. He's bisexual, his father's embarrassed by what he perceives as his son's femininity, so when Saul goes to communist Eastern Europe in 1988, the GDR, he's sort of really experienced an authoritarian regime because his father was so authoritarian, and the GDR is described as the fatherland.

I draw parallels between the micro and the macro. It's another way of saying the personal and the political have to find new language for everything. And Jennifer, she says—there's quite a lot about spectres and ghosts, isn't there, in The Man Who Saw Everything?—she says, "There's a spectre lurking in every one of my paragraphs." What she means is, in a work of art, something is always hidden. All art is about what you reveal and what you conceal. Or it's about making something invisible visible, so when somebody looks at a Rothko painting which is an abstract, they can nevertheless find something in it of their mood perhaps. You can place yourself in that abstract image because Rothko has put paint on canvases with huge emotion. The idea that things are hidden in art, or the idea that we have contradictory thoughts, or the idea that sometimes we are delighted by our thoughts and sometimes we are tormented by them, or the idea that we can actually allow ourselves to think of this thought, which might be an uncomfortable thought, without censoring it, that kind of freedom which art offers is a very precious place at this point in our history. The way that it's written, the form in which this book is written, the sort of behaviour in writing values all those things which I've just said.

When you say it's precious at this point in our history, do you think it is at this point more than any other point?

No, I couldn't possibly ever say that, could I? It seems to me very valuable to be able to think freely. There's quite a lot about Walter Müller in the GDR. Saul says about Walter, "He never speaks his first thought." It's almost like he censors himself and speaks his third thought. It's not so much a case, says Saul about Walter, of him finding a flow of conversation. It's stopping the flow of conversation. There's so much surveillance in the GDR at that time.

There were a few books and movies that came to mind reading this, stylistically. Susan Choi's Trust Exercise, which would've come out after you finished writing yours, but it's a book where the midpoint makes you reconsider what you've read so far. David Lynch's Mulholland Drive, in that there's so many scattered pieces that when you rewatch or reread, these little details become keynotes. I was wondering what works of art you were looking at when writing this?

All of Lynch's films are a big influence on me. The way he structures his films, the way they are so utterly character-led. Lynch spends a lot of time building a character. So does the costume department in his films. Once we can follow the characters, he does all sorts of stuff. Strange ruptures in time, he works with the unconscious and the conscious all happening at the same time. I love his storylines.

Other than Mulholland Drive, which of his do you like?

I think Blue Velvet is a favourite of mine. I watched a lot of Fassbinder movies. Fear Eats the Soul. I listened to some punk bands from 1988, I listened to the Beatles, I spent a lot time sitting out on the wall near my studio in London on Abbey Road, watching tourists cross that zebra crossing. I thought, "Oh yeah, they're enacting a piece of history in a very playful way." I read the historian Tony Judt's amazing book, Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire, a favourite film of mine because that's actually got aerial shots of East Berlin divided by the wall. I taught writing at the Royal College of Art in London the animation department for some years, and I think that I write very visually and think cinematically. You can see that at the top of all my books is sort of a filmic device. If you turn to the book here... [reading] "Abbey Road, London, September 1988." That's something a film would do. I do it in my novel Swimming Home, "A mountain road, south of France, midnight." I do it in my novel Hot Milk. There are a quite a few devices from film that I use in my book.

With something so subtly plotted, how much of that revealed itself during edits and rewrites?

A lot of rewrites. It really takes me a long time, any novel I'm writing, to create the beginning, like the first twelve pages, because I put a lot of information into the first fifteen pages. That's going to develop and unfold a bit like a photograph later on. But The Man Who Saw Everything didn't take me quite as long as Swimming Home. With Swimming Home, I introduce something like eight characters to readers in the first twelve pages. If one of my writing students talked to me about writing that, I'd say, "Why don't you try three?" But I knew it was very important. I had to do it. This book, I did very long writing sessions on it because I had to know, as you can imagine, what was happening on page seventeen when I was writing page twenty-seven, and on page 193 what was happening on page three, because everything is reflecting and mirroring everything else. There's a Jaguar on Abbey Road, the car, and there's a jaguar, a cat, in East Berlin. They're both important. The cat is inside Luna Müller's head because she's got a phobia about cats. But also the Jaguar is inside Saul's head, because the car mirror exploded and shards of that mirror are inside his too. So they're thought experiments, or extended ideas like that. You will find that there is nothing in my books really that is there as a gimmick. There's a reason for everything to be there. That requires quite a lot of plotting and quite a lot of rewrites.

I've read that you're attracted to modernist writers. As a writer with such an apparent style, with what you're doing with form, how do you handle that formal tension against a narrative, and not let one overwhelm the other? It feels like a modernist sensibility.

I guess that the modernism that I'm influenced by is a very spare and economic sort of prose. Quite simple. Quite apparently simple, with a real depth underneath it. The writers that I love are Virginia Woolf, Marguerite Duras, the French writer. Her novel The Lover is one of my favourites. I learned so much about writing and how to structure time from Marguerite Duras. Kafka is good. Katherine Mansfield. Virginia Woolf is so beloved to me, because she's so subversive in this delicate way, you know? Actually, I think modernist novels, or the ones that I'm thinking about, do tend to be quite short. I'm thinking about the British-Scottish writer Muriel Spark as well. I love her prose style. But it's not just modernism. I like novels for all sorts of reasons. My favourite British writer is J.G. Ballard, and he's just a novelist of ideas. He writes terrible dialogue. They all sound like 1950s BBC broadcasts, but I've sort of even become fond of that. It's always like a real intellectual rollercoaster of a ride with J.G. Ballard, and an entertainment because in my view novels have to be a work of art, and they have to be an entertainment. You have to put in the hours to reach that sort of desire in one's self to make that kind of thing.

What about the novel specifically do you love?

Which novel?

Just, the novel.

Which one do I love?

No, the novel as a form. What draws you to it?

Oh! Because you can do inner space, and you can do outer space. You can embody ideas, you can unfold arguments via the avatars of characters. You can go to any place and sort of stroll around, and you can take people at the margins of society and walk them right into the centre of your book. You can make them the centre of the world. When I first started writing, my female narrators who I walked into the centres of the fictional worlds that I was creating didn't have those rights in society, but you can give it to them in a book. You can put words into people's mouths. You can have a go at reaching impossible ideas, and see if you can land them. And most of all, the novel is a very good home for the reach of the human mind, and the mind can go anywhere.

Does it make you feel powerful?

It does make me feel powerful to write. When I started writing, I was a playwright. As a playwright, you're quite literally putting words into characters' mouths, and I learned to edit very quickly as a playwright, because if you write a bad line, that line sort of dies in their mouth, you quickly rewrite it and it begins to work. The pleasure of the novel is really the pleasure and entertainment of ideas and language.