Growing up with four sisters, and no brothers, I often felt misunderstood. When I was four, I dealt with my frustration by shrieking and tearing all my clothes off in front of them. Perhaps it was my way of saying, “See, I’m different.” As a teenager, I kept my clothes on and attempted humour, trying to impress the women I fancied by saying supposedly witty things like, “I have four sisters, so I don’t understand girls at all.” But that was in the 1970s, when our ideas about gender were as unsophisticated as they were rigid. What I didn’t realize then was those ideas—and our strict adherence to them—were part of the problem. When one gender believes it can’t possibly understand another, people are less likely to try to empathize. That lack of understanding and empathy were preconditions for the way some men have treated women.

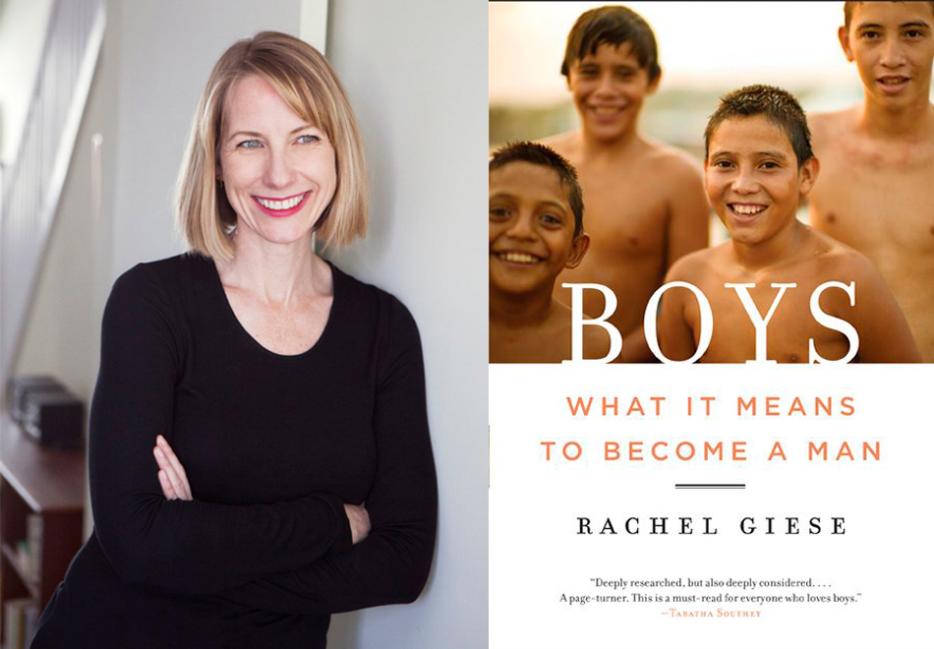

With her new book, Boys: What It Means to Become a Man (HarperCollins), Rachel Giese offers young men more compassion than most of them have shown women over the years. For the respected Toronto writer and editor, the subject of manhood, which had long been of intellectual interest, became personally compelling after she and her wife adopted an Anishinaabe boy. They brought their son up without a former boy around the house to explain what it was like to be a male of the species at a particular age, or help decipher what certain behaviour means. “Which was incredibly liberating because there were no rules in the household about what he should be like,” she admitted. “But there also wasn't a road map.”

So, despite the rule-less liberation, she had lots of questions, including: How do I raise this boy? How do I comprehend what the world holds for him? And how do I help him be good and thoughtful? Of course, lots of mothers and fathers have the same questions (and the parents who don’t should).

And while she knew she might face accusations of womansplaining masculinity, she wasn’t about to cede the ground to MRAs or anyone else who might challenge her right to talk about guys. She set out to figure out what was going on with boys and how to help them grow into good men. Her timing was genius. Although she started working on the book in 2014, when her son was ten, it comes out in the midst of the #MeToo movement, when just about everyone agrees boys and men have to be better people. The result is a thoughtful and surprisingly generous look at a problem that has a lot of people worried or outraged or defensive.

Although spending a few years delving into any subject can lead a writer to some unexpected discoveries, she downplays learning anything too shocking. “I could say I was surprised at how sweet boys are,” she told me when we met at a coffee shop in Toronto’s now mostly gentrified Leslieville neighbourhood, “but why would I be surprised by how sweet boys are?”

How much people cling to the myths of biology was something she found odd, though. In the nature versus nurture debate, she leans to the latter side but realizes there might be some more intrinsic aspects to the way boys are. But it’s so hard to know because we don't exist in a cultural vacuum and there’s no way to do a pure study. The connection between boys and sports, for example, may seem preordained to those on the nature side, but there was actually a great push to get boys into sports in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century because of concerns that masculinity was under threat due to urbanization and industrialization. And girls were not welcome. The Boy Scout movement was part of the same social engineering. So at least some of what many think of as traditional masculinity may owe more to Victorian ideology than to biology.

The prevailing boy narrative today, particularly around the teenage ones, is that they’re not just boisterous but dangerous. As one kid tells her, “Sometimes it feels like adults think that teenage guys are nothing but trouble.” He’s not wrong. And he’s white—the moral panic teenage boys face is much worse when they are Black or Indigenous.

Rather than nothing but trouble, Giese found boys with a broad swath of temperaments and personalities and with a full range of interests and activities and strengths. “Every boy I met was way bigger than the stereotype,” she said. “More complicated, more nuanced.” So, she hopes her book presents a range of maleness that doesn't say there's one right way to be a guy. More than that, though, she argues that the boy stereotype is hugely limiting—and not just bad for women, but for men, too.

If boys are complicated, so is boy culture. The book covers the role of video games and popular culture, schools and sports in the lives of boys. Giese faces her own concerns about video games—she won’t let her son play Grand Theft Auto, for example—and admits that there’s much about sports that she doesn’t like so she lets people talk about what's good about them. Both her wife and her son love hockey. “I don't love hockey, but I love that my son loves it,” she told me. “I love that he has found camaraderie. He's found a sense of mastery. I love that it's a really hard thing that he learned how to be good at. I love that he's physically active. I think competition is not necessarily a bad thing. I think if it's win at all costs, that's a bad thing but I think competitiveness is normal.”

Boys builds to the subject of sex. Giese argues that we’ve long held “basement level expectations” for boys and that the narrative of masculinity is one that says boys are sexually aggressive and that sex is about male pleasure, not female pleasure. We also still have a sniggering attitude towards boys’ sexuality. Making the consent conversation about the 15 minutes before sex isn’t nearly good enough. “We don't just need to say to them, ‘No means no,’” she said. “We actually need them to see girls differently.”

Sex education’s focus on biology rather than relationships isn’t helping. “We don't say to lots of young men that sex can be really beautiful and it can be really meaningful and can be a really powerful way to connect with somebody and it really should be about girls’ pleasure and it should be about mutual enjoyment,” she said. And yet lots of young men and boys would like to hear that message. They want to know how to have a good relationship.

Inevitably, Giese’s fresh perspective is shaped by who she is: a progressive woman who did a minor in gender studies at university in the 1990s. And while she’s certainly not about to indulge any bad behaviour—and knows “certain rules about being a man have led men to do really shitty things”—she’s concerned about and sympathetic toward boys. Giese successfully avoids the lazy generalizations and overused buzzwords that mar much of the discussion on the internet. “If I wrote this book and I went in thinking boy culture, male culture was just sexist and awful across the board, I wouldn't have discovered the things that I discovered.”

But she doesn’t spend a lot of time on what’s good about masculinity. When I suggested that to her, she bristled a bit, and seemed surprised. She then ran through a number of the men she wrote about who are doing great things to help boys and shape the men they will become.I asked her if there are any attributes of traditional masculinity worth keeping. “I think that bravery is a great quality. I think strength is a great quality. I think assertiveness is really useful. I think being tough can be useful at certain points,” she said, but those qualities are worth keeping only if they’re good for men and women. When we tell girls to be assertive and strong and brave, the traits identified with masculinity become the celebrated and enviable ones. Meanwhile, when we don’t encourage boys to strive for the ones—such as tenderness, vulnerability and nurturing—associated with femininity, we denigrate them and they become undesirable. “For me, the problem isn't the attributes,” she said, “it's separating the attributes.”

I don’t envy parents trying to navigate all this. If, as Giese allows, it’s hard to be a boy, raising a boy is even harder. Although she knows there are lots of reasons to be pessimistic, Giese isn’t; she considers herself realistically optimistic or an optimistic realist. “It would be a very hard way of being in the world to be raising the son that I'm raising and feel change is impossible,” she said. “I want him to thrive in the world and unless the world changes, it will limit his ability to thrive.”

Fortunately, her research introduced her to people who are working to help boys be better and who aren’t about to give up. These include men running workshops, after-school programs and other projects. After being thrown out of class in a Baltimore elementary school, for example, kids go to a yoga room, called the Mindful Moment Room, to talk about what they did wrong and do some breathing exercises to calm down. This has led to a dramatic reduction in suspensions at the school. “The whole book is me talking to people who are concerned about young men and who want them to thrive, want them to be emotionally healthy and also want them to recognize the power that they have and use it in ways that are positive,” she said. “I also spent time with a lot of really lovely young guys who wanted to be good and to behave in ways that are decent.”

One scene that stuck with me was the story, in the preface, about her son, then ten or eleven, at an out-of-town tournament with his hockey team. A bunch of the boys were hanging out in his and Giese’s room, giving her a chance to be a fly on the wall as she tidied up unobtrusively. Her son had brought along the teddy bear that had comforted him since he left his foster family. When he pulled it out and gave it a snuggle, she worried his friends would make fun of him for still having one. Instead, they started talking about their own stuffed animals, past or present. For Giese, the male supportiveness was a revelation. It filled her with hope.