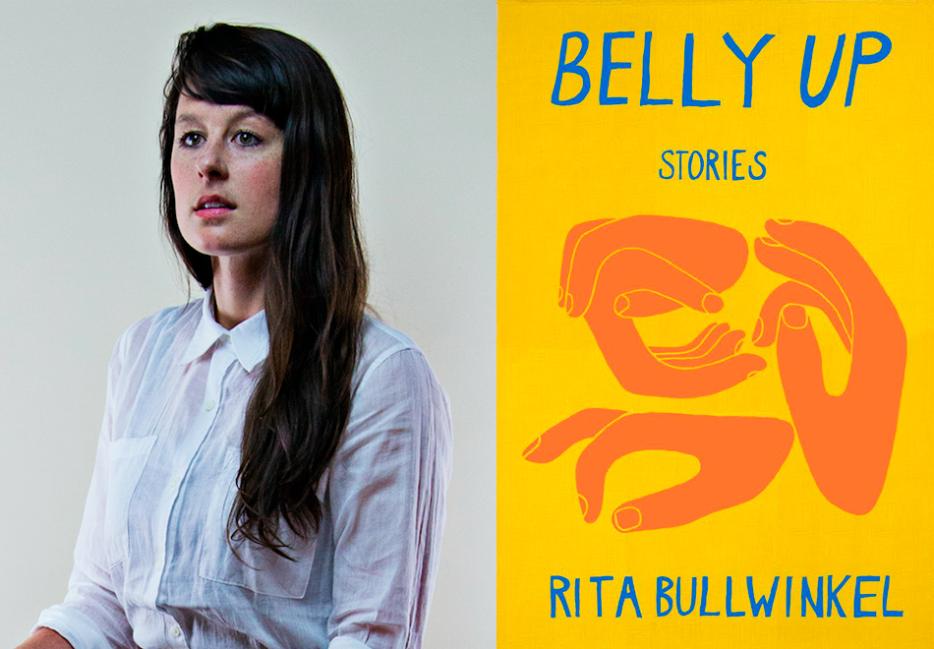

In her debut short-story collection Belly Up (A Strange Object), Rita Bullwinkel traces the fault lines in intimate relationships, and maps meaning onto small exchanges and chance encounters. Characters stick their tongues into electrical outlets, hide food under church floorboards, consider cannibalism, and commune with the dead, among other delightfully odd pursuits. In experimental, surreal-feeling stories that range from two to twenty-seven pages, time is measured in haircuts had, meals consumed, houses constructed, and paintings finished. Bullwinkel dares to build terrifically offbeat, imagistic worlds in quiet, often rural places (a double-wide trailer in an Oregonian park, an “Easter-blue” house in Florida, and an algae-coated pool in rural Texas).

The most compelling stories center a conspiratorial narrator and highlight darkly funny details (in a scene that takes place in a prison infirmary, a surgeon almost grafts a left thumb onto a prisoner missing his right). Weaving pithy bits of dialogue into economic sentences, Bullwinkel captures subjects on the brink of collapse or calamity or fugue state—lending the collection a degree of emotional intensity.

*

Anna Furman: Odd jobs crop up a lot in these stories—a medium, a breast-holder, a furniture saleswoman. What sort of odd jobs have you had?

Rita Bullwinkel: All jobs are odd, in their own way. One of the strangest jobs I’ve had is working the graveyard shift at the Chelsea Market Anthropologie store in New York City, where management made employees memorize narratives of five fictional women for which specific parts of the store were designed. These fictional women were supposed to embody the main categories of Anthropologie shoppers. Some had real names, like Claire, and some had fake names like Nomad. Nomad was a little crunchy and went to Paris for the weekend with her boyfriend and loved shopping at the Brooklyn Flea. One day a month there was even a staff wide costume contest to see who could best embody the essence of one of these fictional women invented by corporate. Sometimes my manager would give us pop quizzes about what the women did over the weekend. We got updates on their lives via weekly emails. The winner of these contests always got a $25 Anthropologie gift certificate. I really hated that job.

Does anyone in your family work in publishing?

No one in my family works in publishing or reads much fiction. Everyone in my family has read the book, which I think they find eccentric. But, I think they find that writing books, in general, is eccentric. It’s not my specific book they find strange. My father had the best response to the collection. He is a methodical man, so his response was methodical. He documented his reactions to each story, and then sent me a document with notes like: “Concerned Humans: Identity confusion. Consumption confusion. Poison or safe confusion. Satisfaction confusion. Life is complex!”

In some stories the characters have specific names, and in others they are generic, as in “What Girl Built.” Why didn’t you give Girl a name?

Partly for the sound of it. I like the way Girl sounds in the mouth. There can be a special power that comes with not naming your characters, or giving them an archetypal name. A master of this is Yuri Herrera, especially in his brilliant novel Kingdom Cons.

“Mouth Full of Fish” takes place in Balmorhea State Park in Texas. Have you traveled there? How did your visit inform the story?

I went to Balmorhea the summer after I graduated from college. My partner and I drove a really shit car across the country and then sold it when we got to California. We took three months to drive from Providence to Tampa, Florida, where he’s from, and then from Florida to San Francisco, where I’m from. We stopped in Marfa, which I really hated. It felt like a bunch of very rich, beautiful New Yorkers transplanted into the middle of Texas. Everybody seemed like they were from Chelsea. It really disappointed me. The Chinati foundation is very beautiful—I won’t deny that. But the rest of Marfa is total garbage. We stayed in a yurt that was very expensive. When I asked the woman who managed the yurts how to get to the Prada store, she said: “There’s no store. There’s only art here.” And I was like: “OK. Can’t you just give us directions to this place?” We never found it.

After Marfa we drove to these hot springs in Balmorhea, and it was everything I wished Marfa had been. The sides of the spring looked like a pool, which is very disarming because the bottom is uneven and rocky and has algae on it. We stayed at a motel near the springs and there were these beautiful sky-blue benches and sun-bleached, dead animal bones hung everywhere as decorative pieces. I spent sixteen hours there.

I was unclear what the narrator’s gender was in the story. And several other stories are written in this way, centering a narrator whose gender is somewhat ambiguous. Was that intentional?

Yes. While I was writing “Mouth of Fish,” I decided that fundamentally the gender didn’t matter. There was never a draft in which the character had a specified gender.

The last story, “Clamor,” is roving and expansive; it’s told from the perspective of a third person omniscient narrator. This wide-reaching vantage point affords the reader a degree of access to several characters’ psyches, which makes it unique from the other stories in the collection. Is it based on a real event?

My grandmother, who is recently deceased, did take my sister and I to visit a medium in Oregon with the hopes of connecting with her dead husband, my dead grandfather. But she was always doing things like that, so it’s not like that story, “Clamor”, is about a specific time when we went to go see a medium. She frequently would try to get my sister and I to connect with our grandfather through a medium, either over the phone or in person. I had a lot of forced experiences with mediums when I was a child. I was always skeptical of them and felt very resentful of them. I thought it was ridiculous that a stranger might know more about my grandfather than me, or have access to him in some way I didn’t. But my grandmother believed in it.

Did your grandmother read the story?

No, she died in her sleep three months ago. I was planning on sending her a galley but she died before the galleys were printed. I don't know if she would’ve recognized herself, though. I wrote a story, once, where I verbatim used language that she had used to give me advice about plastic surgery, if I ever decided to get some. She read the story and said, “This is all such excellent advice! So practical. How nice of you to share it.” She didn’t see any of herself in it. You never know how someone is going to read something. I wasn't scared that she was going to be offended or anything like that.

Can you tell me a bit about your decision to apply for MFA programs?

When I was applying to graduate school, I told almost no one I was applying, because I thought that the likelihood of me being accepted into a program was basically zero. It was something I wanted so badly that I felt I couldn't talk about it. So much so that when I was admitted to a few programs, some of my family members and friends felt like I had lied to them, or purposefully kept my writing life from them. Many of them hadn’t any idea that I had any interest in writing at all, and felt that I had been writing in secret, covertly, which is not how I was thinking of it.

I was very surprised when I got into programs. I only applied to programs that gave full funding to everyone that was admitted because I knew that’s what I would require to go. I am very grateful to Vanderbilt. They accept three fiction writers a year, and their funding is very generous. I made more money going to graduate school than I ever did working in New York City.

It’s very rare to be in a place where you are being paid to make art and an institution is telling you that that is what you’re there to do. And that is something that Vanderbilt made very clear. It’s something that no one in my life had previously given me the license to do. More than the money, it was not something that I would’ve been able to convince myself of on my own, that making stories was something that I should be doing. I needed someone else to tell me that it was something that I should be doing. Vanderbilt gave me the ability to say out loud what I’m doing: trying to write something.

Do you have a person in mind that you’re writing to?

The brilliant poet, Tiana Clark, says that her ideal reader is a waitress at PF Chang’s reading her poems on their five-minute break, which is how Tiana fell in love with poetry.

Perhaps every writer desires a reader to feel about their work like they felt about words the first time literature lit them on fire? I didn’t read fiction at all until fairly late in college. I thought I didn’t like reading because I had been given very boring things to read. The common core of the California state public education system is full of banal literature that is either so old it’s irrelevant—no one’s debating that Macbeth isn’t important—or you have to re-read the same thing a bunch of times in different grades. I was assigned To Kill a Mockingbird six times and The Catcher in the Rye two times, and I kind of thought, well, I guess these are all the books that exist, and they’re kind of boring.

What I’m trying to say is that I wasn’t some super well-read literary reader. I’m terribly read. I’m always playing catch up. I am still trying to make up for all the years I spent growing up not reading the right books.

So I wouldn’t want my “ideal” reader to be especially literary, whatever that means. Books get labels like “literary fiction,” which implies that they’re meant for a certain type of person that isn’t the type of person I am, or ever will be. I would be much more excited to be read by the waitress who has no idea where Vanderbilt is or what literary fiction means. Maybe my ideal reader is a poet? That would be a compliment for me. I try to make sentences that sound pretty.

What do you think can be accomplished in a short story that might not be as possible in another form?

I think that short stories have the ability to be read in one reasonable sitting, and that that gives them a special power. I often think about how the time that one spends in consuming a piece—whether it be music or a painting—is very involved in the emotions it elicits. Time is a strange thing in writing, because compared to other works, it takes a great deal of time to consume and it’s an all-encompassing consumption.

The time it takes one to read thirty pages, perhaps the length of the “typical” short story, is a potentially resonant time to spend with something, which is like forty-five minutes or an hour, similar to something like a movie. I think that is unique with the story.

However, whether it be a poem or an essay or a novel, genre isn’t really an important grouping, writing is still the most effective art form we have to inhabit the consciousness of another. I think that’s why I’m more moved by writing than any other art form. It seems so amazing that one can sit in the thoughts of another so thoroughly that one begins to question if they are thinking these thoughts. It’s like the opposite of voyeurism. That’s what I love about reading.