Sandy Island does not exist; this we now know for sure. Sandy Island died—it has an obituary.

Sandy Island lived for more than two hundred years, appearing first on a 1908 British admiralty map at 19°S, 160°E. In 1876, the whaling ship Velocity reported a fifteen-mile long sliver of land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, about five hundred kilometres northwest of the French colony of New Caledonia. The captain named it Sandy Island.

Scientists now suspect it was a giant, floating pumice bobbing in the Pacific fog. Recent studies have determined that the coordinates of “Sandy Island” bordered an oceanic “pumice superhighway,” clogged with the byproduct of volcanic explosions. But no one knew any better then. For more than a century, no one had thought to question the wobbly paper marks of a whaling captain on choppy seas. Sandy made its way from nautical charts to the World Vector Shoreline Database and eventually, inevitably, into Google Earth, where, if you went looking, it appeared as a black pentagonal square.

It took a pair of amateur radio enthusiasts, on an expedition in 2000, to suggest, in whispers, that the island might not exist at all. In 2012, a scientific exploration investigating the eastern Coral Sea aboard the R/V Southern Surveyor passed through Sandy Island’s coordinates multiple times. There was nothing there, and the water was too shallow for the land to have sunk—they had officially “unfound” Sandy Island.

In his new book, The Un-Discovered Islands: An Archipelago of Myths and Mysteries, Phantoms and Fakes, Scottish author Malachy Tallack asks: “How could an island have slipped through the net of satellite technology for so long?” The answer is remarkably simple: Sandy Island had been placed in ink on a fallible nineteenth century map, and believed in until proven otherwise.

Tallack grew up on Scotland’s remote Shetland Islands. His school’s motto pledged allegiance to an unfound island thought in Roman times to be the most northerly point of the western world: “Thule.” Dispecta est Thule curled in wrought iron on his school’s gate—Thule was seen. So, too, was Sandy. “Many were drawn to this episode by the idea that what are taken as baseline truths—world maps—may not actually be true,” Sandy Island’s obit in EOS, Transactions, American Geophysical Union magazine concluded.

Historically, many unfound islands have been in the Pacific Ocean. Dougherty Island, off the coast of New Zealand, took its name from the captain who spotted it, though he never stepped foot on land. Some historians suspect that his fishermen mistook an iceberg through the fog for land itself. Emerald Island, thought to be located by a sealing vessel between Antarctica and Australia, wasn’t unfound until the 1980s.

Theories are varied as to why “phantom islands” persist. There is considerable debate in the realms of philosophy and science as to how and why a concept—or place—is eliminated. The “unfinding” of Sandy Island, says a recent study, is the perfect example of the modern confluence of technological truth and mythological attachment. There is proof of the fallibility of our institutions but only if you go looking for it.

In the late nineteenth century, the British decided to “clean” the world’s maps of superfluous islands, particularly around the Arctic and Antarctica. Tallack writes that we are now in an age of “undiscovery” that is experienced, confusingly, as human loss alongside enlightened progress. “We are paying for cartographical completeness with a feeling that something, somewhere, is missing,” he writes.

*

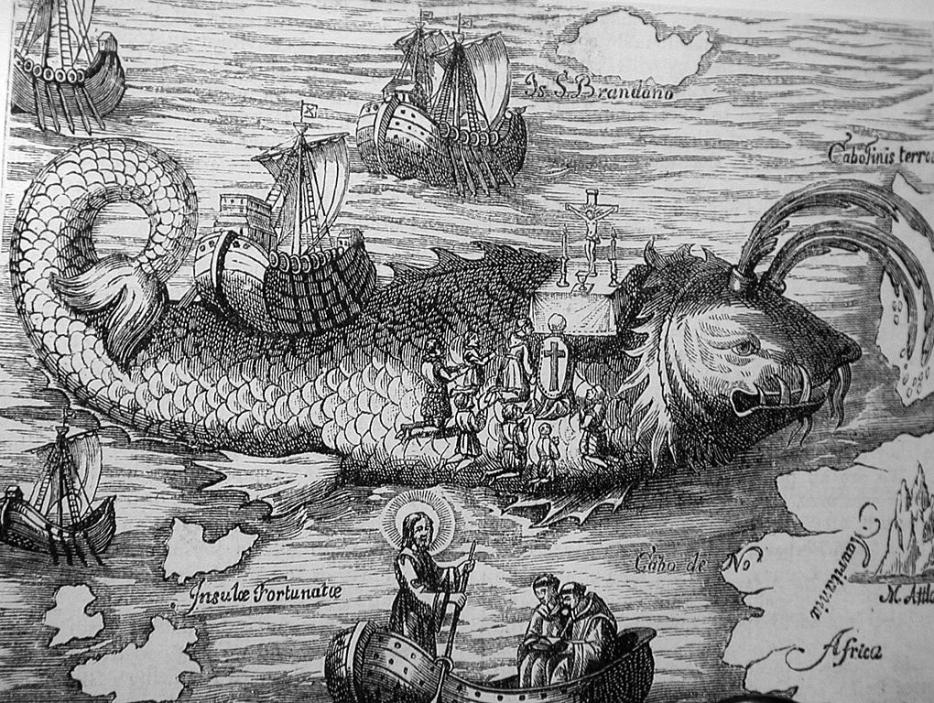

In the Middle Ages, an Irish monk sketched an island on a map and named it the Island of San Brandan. The island, it was said, had the power to emerge from, or submerge entirely within, the sea at the whim of the fates. It was illustrated next to St. Brandan himself, standing arms outstretched towards his namesake.

But the island did not exist. It was a work of fiction inspired by the fantastical stories of Johan de Mandeville, who wrote of griffins and cyclopes, headless figures whose faces peered out from their trunks, dog-men, of apples that fattened women just at the smell. And, it so happens, of disappearing islands in the middle of seas.

These prophecies influenced geographers, who drew connections between the literary and the physical. They placed those magnificent worlds on maps without question. Their fantasies would dissolve in the shadow of the Enlightenment a few hundred years later, but the basis of cartography—springing from realms just beyond reach—would continue to be rooted in these tales. Wild worlds existed until they were disproved. The Island of San Brandan rested just to the west of the Canary Islands, halfway between there and the Azores, on maps and globes well into the 1500s.

Historians of science believe the first attempt to translate mythical land into concrete geography took place in the seventeenth century, by Scandinavians interested in Viking mythology. Soon, islands of the mind would be usurped by an explosion of geographical research, those pieces of land tracked on the trails of celestial navigators at the end of the nineteenth-century. But even they were tricked.

*

I once lived on an island that was in danger, twice in six months, of being flooded. Haida Gwaii is low-lying and an eight-hour ferry ride from the coast of British Columbia. Two large earthquakes had instigated the risk there of tsunami washing up on shore from Alaska, just to the north. I thought a few times about how tsunami survivors in the Philippines held onto the tops of trees as the tide swept them up.

The futile precaution against this cold and watery death was to follow a tsunami evacuation route along the only major highway to the highest point on the island and wait out the warning with the rest of the residents. It was very apparent that the tallest part of the island was not tall enough. We were standing on the future ocean floor.

Would Haida Gwaii become unfound, erased by a surging wave? Would it be wiped off the map? An island can disappear in less than ten minutes, I learned. We’d all be dead in our cabins or on the road to safety.

In the end, the shaking served only to disconnect the hot springs in a national park. The ground shifted again, about a year later, and they sprung back.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts that, by the end of this century, various low-lying island states within the South Pacific and Indian Oceans could become totally immersed by rising waters. One day, the Republic of the Maldives could be just as “unfound” as San Brandan or Sandy Island.

The disappearance of an island is a kaleidoscopic dissolving. When a chunk of land disappears, does it take with it its culture, language and history? Some have suggested that money be poured into a reconnaissance mission that would construct artificial islands to replace the sinking land. But does a state exist if its land is entirely built, not naturally appearing? Likewise, some international migration lawyers have suggested appropriating or accepting donations of land from other countries, plots onto which nationhood could be transferred. In this instance, because these countries are home to people, the Maldives can only truly be unfound on paper: its identity and statehood will live on above water.

*

“Not only is it easy to lie with maps, it is essential,” writes Mark Monmonier in the first pages of his treatise How to Lie with Maps. “To portray meaningful relationships for a complex, three-dimensional world on a flat sheet of paper or a video screen, a map must distort reality.” When we look at maps, most of us, he argues have suspended disbelief for a moment, have trusted that the mapmaker knew their coordinates and their borderlines. “Because of personal computers and electronic publishing,” he wrote in 1996, “map users can now easily lie to themselves—and be unaware of it.” Our digital lines look sanctioned, but they are essentially our folk maps, etched by hand, snapped to a grid.

In 2016, according to Google, a “bug” accidentally removed the labels for the West Bank and Gaza on Google Maps. When activist groups noticed, outrage ensued—a hashtag, #PalestineIsHere, was deployed and a petition was circulated to get Palestine “back.” “The move is designed to falsify history, geography as well as Palestinian people’s rights to their homeland,” read a statement from the Forum of Palestinian Journalists. Five months before the Forum had mounted their scathing criticism, a Change.org petition asked for 500,000 signatures to petition Google to put Palestine on the map. Now, it’s demarcated with light dotted grey lines but remains un-labelled. Microsoft’s Bing maps label Palestine as a country.

Google Maps, globally our most ubiquitous cartographer, is—dangerously and admirably—partly crowdsourced, and so not immune to the ideological whims of political and social upheaval. Aiming to dispassionately track the world’s borders, Google Maps instead is a living and breathing document that’s easily altered in real-time. “This is not an issue that’s easily resolved,” says David Bodenhamer, a scholar of cartographical history and philosophy, of the political power behind the creation and maintenance of maps. “But Google has a commercial interest for everything that it does, and its main purpose is not so much to avoid doing evil… the imperative is pushing up against any interest that national governments might have in protecting certain things.” Google’s reliance on users to report shuttered restaurants and new contact information brings with it the enormous power to find or un-find a place.

*

"For years, archaeologists believed that the Arginusae islands in the Aegean Sea were the product of myth and storytelling. The Arginusae (now called the Garip) are located off the shore of Turkey, close to where the ancient Greek historian Xenophon pinpointed a sea battle between Athens and Sparta. His words pointed to three islands, but until 2014 one had been missing. On that island would have been the city of Kane—small but important along a Black Sea maritime trading route. In 2014, archaeologists drilled into the earth, finding in the depths the third. Once an island, it eventually became a peninsula, attached to the shore by a land bridge formed by erosion and earthquake debris.

And so, the unfound had returned. “The notion of discovery is now a notion of re-discovery, things we thought had once existed and were then lost are now found again,” says Bodenhamer. He wonders if finding a once-lost island brings with it a stronger connection to Greek history and identity for the Greek people. The battle that took place from the port of Kane, for instance, was won by the Athenians who were then socked-in by storms and unable to save surviving soldiers whose ship had been damaged. Kane, home to bittersweet victory and defeat.

“Maps may be flawed, but at least they are familiar,” writes the philosopher of science Larry Dossey. “And because they are familiar they make us confident.” The digital age is no different—Google Maps is a fallible god, the first place we turn for answers, our backbone on familiar and unfamiliar terrain. And yet, and yet: “We all had a giggle at Google,” said a scientist on board the Southern Surveyor, “as we sailed through the island.”