At the age of twenty, Christopher Knight walked away from civilization and set up camp in the woods of central Maine. There he remained, near North Pond, undetected, for twenty-seven years. He survived on stolen provisions and a determination to live in solitude.

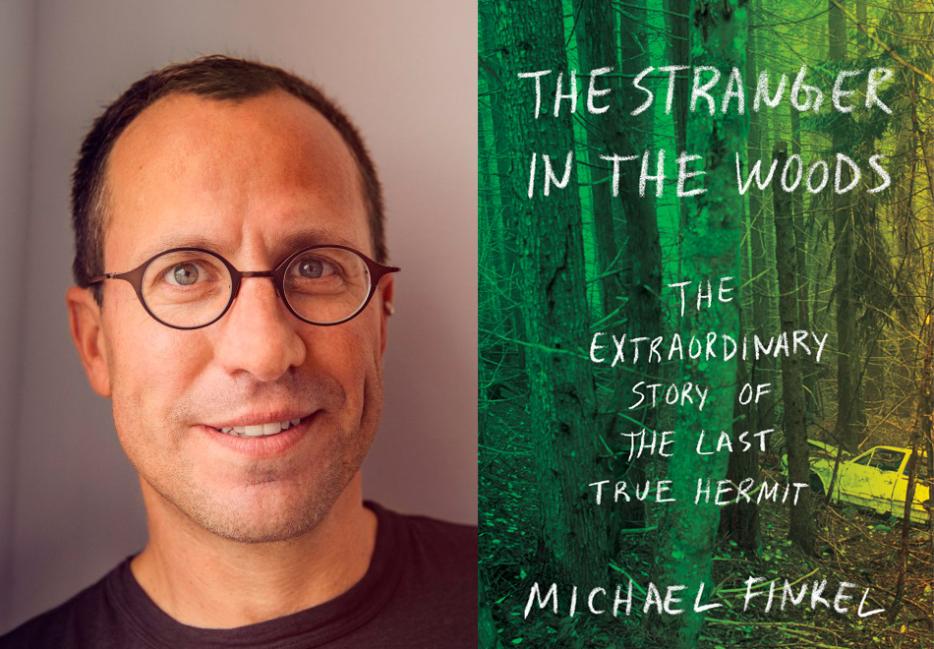

In The Stranger in the Woods: The Extraordinary Story of the Last True Hermit (Knopf), Michael Finkel tackles the story of the famed North Pond hermit. He portrays a man who, without a shred of formal outdoor training, survived through ingenuity and remarkable self-discipline.

Many readers know Finkel as the author of True Story: Murder, Memoir, Mea Culpa (2005)—later made into a movie—which chronicles his torturous relationship with an alleged murderer who stole his identity. The tale is all the more bizarre because it began just after Finkel was fired from The New York Times for fabricating part of a story.

Here, Finkel approaches the North Pond hermit with genuine humility and writes about him with insight and compassion—perhaps because of his own flawed past. He examines the fascinating tradition of hermits throughout history, and describes the allure, and the very real dangers, of long-term isolation. And he poignantly chronicles his own efforts—never entirely successful—to build a relationship with this inscrutable man.

*

Tucker Coombe: How did you initially become interested in the North Pond hermit?

Michael Finkel: I’m an avid outdoorsman, and I love to read. One day I came across a small article about a man who was arrested for stealing food from a summer camp. The article told a fantastical story: the man had apparently spent twenty-seven years alone. In all those years he had never lit a fire, had a conversation with another human, or even been sick. My curiosity started ratcheting up. The last thing the article mentioned was that this man had stolen books—hundreds, perhaps thousands, of them. My curiosity turned to compulsion, and I decided to write him a letter. I doubted that I’d hear back from him, but to my surprise, he wrote back.

From the first paragraph of his first note to me—which was witty and extraordinarily well written, and intelligent and sad at the same time—I was hooked. I wanted to know Christopher Knight’s story.

Knight had no survivalist training, and in fact had never spent a night in a tent when he decided to move to the woods. How did he manage to survive?

If you read about hermits throughout history—people who wanted to separate themselves from all other people—an extremely high percentage of those people have been bright. I think Chris Knight was brilliant.

He was also an amazing student. He understood aspects of physics and thermodynamics. He could change the oil and repair electric things and do the plumbing. He could recall details from every book he’d ever read. He could fix an engine and quote Shakespeare.

He was also committed to being alone in a way that’s hard to get your head around. He didn’t want to light a fire, for example, because the smoke could give away his location. In Maine, snow persists on the ground for half a year, and there were times when he’d stay in his small camp for six whole months—coming to the brink of starving or freezing to death—because he refused to walk through the snow and risk leaving a footprint.

How did he do it? He figured it out.

Your book opens with a vivid description of the woods where Knight lived for twenty-seven years. Tell me a bit about those woods, and about the camp he built there.

You might think Knight would choose a site up in the North Woods, but he didn’t. He actually lived in an area where there were about 200 cottages situated nearby. The camp he built for himself was a three-minute walk from the closest cabin.

But the woods themselves! If you imagine a Brillo pad the size of a football stadium—well, that’s how dense those woods are.

I’m a fairly decent woodsman, and I can’t overemphasize how challenging, how difficult and crazy it was to walk through those woods. I cut my hand open and ripped my shoe. The trees are skinny and closely packed. Lots of them are fallen, so it’s as if you’re walking through a giant game of Pick-Up Sticks. It’s chock full of boulders, and there are no trails. The undergrowth is full of ferns, mushrooms, and tree branches. It’s claustrophobic and disorienting. Even deer don’t go there very often. But Chris Knight could move through these woods—without making a sound—in the middle of the night.

There are two distinct-looking boulders next to each other, and if you pass between them, you enter what feels almost like a room in the woods. Tree branches link overhead, and the space is ringed in a natural Stonehenge of large rocks.

I’ve had the opportunity to travel the world, but here in Maine, inside this little patch of forest, is one of the most enchanting spots I’ve ever seen. I can understand why someone like Knight, who’s highly sensitive to noises and disruptions, found the spot to be an oasis of calm.

You describe spending a night in this camp, and being awed by what Knight had created.

As a camper myself, I wondered how Chris had built this camp. It was as if he’d invented a world for himself in this spot. He had a tiny kitchen, which consisted of a stove that he had stolen. He cooked with propane—he stole propane tanks as well—instead of a fire.

He had bound together old National Geographic magazines with electrical tape, creating bricks of a sort, which he used to build a floor. It was perfectly flat, which prevented water from pooling in his tent.

Everything was neatly and precisely organized. There were some touching things about the camp, as well. He had only one chair. And he had tons of books.

He didn’t care about the year or the decade. But he cared very much about knowing what time it was, so that on raids, he could get back before sunrise. He had a little weather station. He listened to the radio. He didn’t believe in sharing anything, so he never wrote anything down. He thought he would die out in those woods. Other people have tried to live in the wild, and many have died in a very short time: somehow, he made it work. It was semi-miraculous.

How did he survive the Maine winters?

Maine winters are brutal—cold, windy, and unbearably wet. You could spend one night outside in a Maine winter and probably never forget it and probably never do it again. I wondered what Chris did in winter. He used the propane stove to melt snow, for drinking water, but wouldn’t use it for heat because the fumes would have killed him. When we spoke about the winters, I said to him, “You must have gone into a sort of human hibernation––cocooning yourself in every stolen sleeping bag you had.”

“You’re absolutely wrong,” he said. The human body breathes, he reminded me, which creates vapor. Chris didn’t want to find himself covered in frozen condensation, and risk dying of hypothermia. So he’d wake up at 2:30 in the morning, which is the coldest time of the night. He‘d unwrap himself from his layers of blankets. And he would begin pacing. He knew that if he were to stay still, the cold would march from his fingers and his toes right to his heart, and stop it. He would just walk in circles. And you know, he never lost a finger or a toe to frostbite.

To me, it sounds like torture beyond torture. But for some reason—in his suffering, and in that sort of extreme state—he found fulfillment. I will never encounter another human being that lived life on the edge the way he did.

He found contentment for himself. But he survived by stealing from others. Did he feel conflicted about this?

Yes, he was conflicted. He had been raised in a family where education, learning, and self-sufficiency were all considered important. And he was taught that you do not steal. But he made the decision that he would have to steal if he were to survive. And to assuage his guilt, he created a set of rules for himself: he never broke a pane of glass. He never kicked in a door. He never stole anything of great monetary value. Only once was a person in the home when he broke in, and Chris felt terrible for having frightened that person.

He would enter a house by very carefully picking a lock. He wouldn’t touch the jewelry, the television, or the computer. He’d take what he needed, and when he left he’d lock the door behind him because, well, there were real thieves out there!

Chris would be the first to say that he’s not a saint. There are lots of gray areas, lots of moral complications, in this story.

People in Maine seem to have had strong reactions toward Knight.

Personally, I feel warmly toward Chris. But let’s not forget this: the man broke into people’s homes. Repeatedly. In some states, you can legally shoot to death a person who enters your house uninvited. That’s how sacred a home is considered. And what he stole was people’s sense of safety and security. I’ll say this as well: if you steal my laptop, I can get another one. But if you steal my sense of safety and security, that can’t be replaced. It’s more valuable than diamonds or jewelry. So, to some people, what he did was terrible.

Other people thought he was no more trouble than the seasonal houseflies. And on one level, the list of what he stole is almost laughable: hamburgers, steaks, and paperback books. Magazines and flashlights. Some people, even after the second break-in, just shrugged. “I can buy another flashlight,” they reasoned. “I throw away that amount of food every week. And I’d already read that Stephen King novel.”

On this planet, we don’t know what to do with people who don’t belong. I don’t mean murderers, or people who are, clearly, mentally insane. I’m talking about someone like Chris Knight, who was a gentle person but who didn’t fit in with the rest of us. It’s heartbreaking. We don’t have a spot for him. There were a significant number of people in Maine, victims of his crimes, who intuitively realized there was someone living in the woods who just didn’t want to be part of society, and they were very sweet about it.

It turned out that the woods where he lived for all those years was private property, owned by a woman who lived alone. I thought she might have been horrified when she learned that a strange man had been living on her land for twenty-seven years. Do you know what her response was? “So what,” she said. “If I had found him, I might have just let him stay.”

If your reaction to Chris Knight is that you hate him, then that’s totally valid. If your reaction is that he’s your hero, that’s equally valid. He provokes very disparate feelings in people. I’m not saying anyone’s reaction was right or wrong. But the way people reacted to Chris Knight spoke less to who Chris was, and more to who they were.

You spend a lot of time discussing human isolation in this book.

Strangely, across all of human history and going back thousands of years, there have existed a tiny handful of people who’ve simply wanted to be alone. What’s fascinating is that many of them have had profound effects on the world. Think of Jesus, Mohammed, and Buddha: they all spent very long periods of time alone before introducing their religions.

Chris Knight had no interest in anyone else. He wanted to be by himself in the most extreme way. It’s hard for most of us—the 99.9 percent of humans who don’t want to live like that—to get our head around this concept.

I found him to be a singular human being. He certainly confessed to his crimes. He never said he shouldn’t be put in jail. But he also had an idea for how he wanted to live. And despite the fact that it was radically different from the way anybody else lived, he ignored all the pressure of society and went to live exactly as he wanted.

Chris told me that he found contentment in his isolation. And I could just tell, from the way he described it, and the way his face changed, that he had been happy out in the woods. I think he found more fulfillment than most of us will ever find in our own lives. He found something deeper and richer.

Your discussions with Knight seem to have shifted your own perspective on humans and happiness.

Encountering a person like Chris affected me profoundly. Sometimes I find myself in my car, stuck in traffic. Texts are coming in on my phone. I’m stressed. I’m late for an appointment. And I think: maybe it’s not Chris Knight who’s crazy, maybe it’s the rest of us. Maybe he got something right, and we’re the ones who got it all wrong.

What did Chris Knight do? He made me take a step back, think about the choices I’ve made personally and the choices we’ve made as a species. Look at the political climate now, and the craziness that’s going on. We don’t even know what truth is anymore. It makes me want to run to Chris’s spot in the woods.

More than a decade ago, you wrote True Story. You developed a relationship with a pathological liar—an alleged murderer—at a time when you were struggling with your own issues of honesty. For this book, you developed a relationship with Knight. Is there some aspect of his story that resonates with you at this juncture of your life?

As a journalist, I try to understand other people and their stories. But the truth is, each of us can only really and truly know one person––our own self.

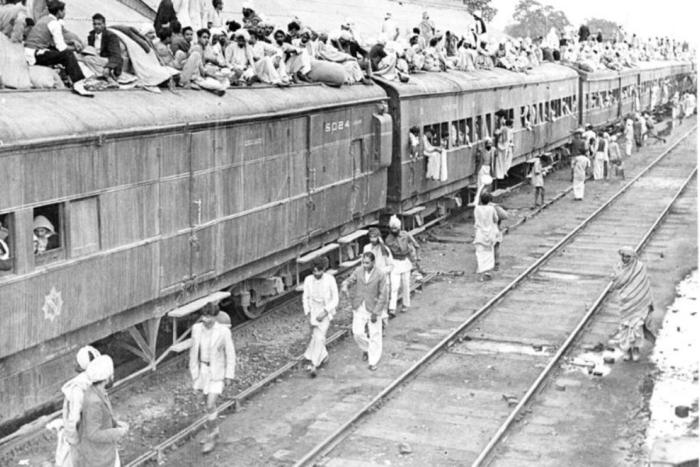

Years ago, I went to India for a ten-day, silent retreat. I wanted to make myself go where I was afraid to go—deep down, inside my own head. I found it terrifying. Why don’t we want to be alone? Because the stuff that’s down there is stuff you don’t want to see.

Chris Knight is a guy who went all the way down to the bottom. He saw the whole thing. He did something that I was frightened to do. What did he see? What did he learn about himself? What does it all mean? I couldn’t do it myself. I wasn’t a strong enough person, and he was. That’s what attracted me to this story.