Leonard Cohen has always had a reputation for making sad music. It’s easy to picture the well-worn cliché of the college student laying crestfallen in bed with Songs of Love and Hate wafting from their speakers—such is the power of Cohen’s writing that he’s become synonymous with longing and desire. But this characterization strikes me still as an oversimplification: Cohen’s music always exhibited a curiosity for words and their elasticity that was frequently playful. Life contains peaks and valleys (don't we know it here in 2016) and so should songs.

Upon hearing of his death at the age of eighty-two, sadness wasn't the primary emotion that struck me—instead, his passing has elicited something like a joyful wistfulness. Of all people on this planet, Cohen behaved as someone clearly in on the cosmic joke of life. After casually declaring in the New Yorker in October that he was “ready to die,” he responded to that statement in Billboard by stating “I intend to live forever.” He was our man, a guy who joked about eternal life and died a month later.

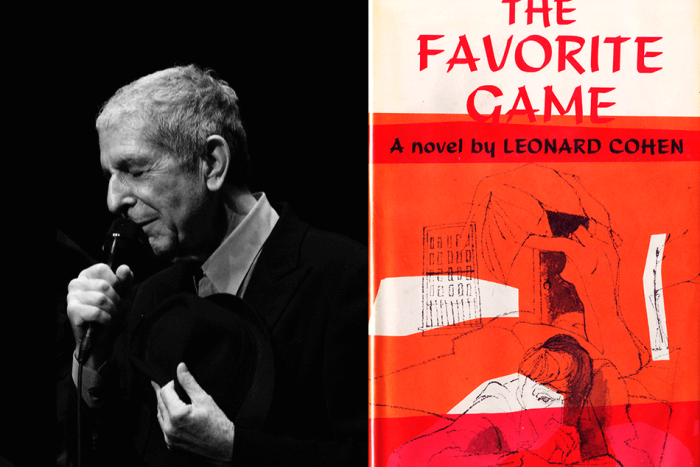

His writing frequently skirted the lines between life and death, pleasure and pain, physical passion and spiritual awakening, in a way that was artful but not showy. Cohen demonstrated that there is no one singular path for an artist over the span of their career. He released his first album in 1967 at thirty-three, an age when most pop musicians are already starting to go downhill. Commercial success was not consistent. He spent his twenties doing acid, making love and writing poems on Greek islands, living the life of a genuine literary celebrity whenever he would return to his native Montreal. He was swindled out of millions by his former manager, Kelley Lynch, and went back on tour in 2008 after a fifteen-year hiatus to repair his finances.

In both his music and poetry, Cohen’s writing was louche without being lascivious. He helped liven up the then-dry world of folk music with his occasional sprinkle of sensuality. “Don't Go Home With Your Hard-On” from the Phil Spector-produced career diversion Death of a Ladies’ Man is a more overt example. But despite the fact that his appreciation for the opposite sex was ever-present in his career, it never felt like a carnal obsession. To Leonard, it was simply an aspect of life worth elucidating.

One of his signature songs, “Famous Blue Raincoat,” is written in the form of a letter. It concludes with "Sincerely, L. Cohen," a sign-off both emotionally powerful in terms of content and knowingly humorous in how it is deployed (yes, we know who wrote this letter, as if it could be anyone else). He never really received enough appreciation for the subtle skill in his songwriting, occasionally criticized by rock publications of his time for his gravelly voice and limited vocal range (his sarcastic response: “I was born like this, I had no choice / I was born with the gift of a golden voice” on 1988’s “Tower of Song”). Some of the best music writing I've read this year is Bob Dylan describing what makes Leonard Cohen's music special in the previously mentioned New Yorker profile about him:

“‘Sisters of Mercy’ is verse after verse of four distinctive lines, in perfect meter, with no chorus, quivering with drama. The first line begins in a minor key. The second line goes from minor to major and steps up, and changes melody and variation. The third line steps up even higher than that to a different degree, and then the fourth line comes back to the beginning. This is a deceptively unusual musical theme, with or without lyrics. But it’s so subtle a listener doesn’t realize he’s been taken on a musical journey and dropped off somewhere, with or without lyrics.”

It's hard to get Bob to respond to anything these days, but look at him go when the subject is Leonard Cohen. He had that effect on artists of all stripes, the songwriter’s songwriter, a man who applied a monastic dedication to the power of song. He reportedly worked on “Hallelujah” for five years; that song starts with his classic discussion of the so-called secret chord being immediately cancelled out by a disinterested listener: “But you don't really care for music, do you?” How ironic that this typically Cohen-like inversion happens in a thirty-two-year-old song that feels as ancient as music itself and seems as much a part of our natural environment as the side of a cliff or leaves falling in autumn. This is how he intended to live forever.

Like so many people around the world, Leonard Cohen influenced my writing and my love of poetry. But particularly as a citizen of the north country, he changed the way we perceived ourselves. He helped develop the urbane, cosmopolitan profile that so many of us proudly cling to as our cultural identity. But most importantly, he helped make being Canadian romantic. And for that, I will always love Leonard.