Sam Wiebe’s Invisible Dead is tagged with many of the adjectives you’d associate with a new urban private-detective story: noir, gritty, hard-boiled—and the book deserves them all. But it also accomplishes what Richard Price’s novels and David Simon’s television shows do: it presents a city as it is, with the kind of detail and depth that become possible when you follow a crime through many urban layers of class, race, and society.

Price’s Lush Life built a precise portrait of Bloomberg’s gentrifying New York out of a mugging–gone-wrong that leaves a cocky bartender dead outside the upscale and projects-adjacent restaurant where he works. Wiebe’s city portrait touches on gentrification, but the crime at the center of Invisible Dead is grimmer, less accidental, and speaks of a social toxicity that goes deeper than economics.

In this case, the city is Vancouver, and the crime is the unexplained disappearance of Chelsea Loam, a First Nations woman who works in the sex trade. Dave Wakeland, 29-year-old ex-cop and current partner in a detective agency that allows him to spend time on his own cases in exchange for his assistance in corporate bodyguard and security commissions, pursues the vanished woman through his own past and into Vancouver’s worst places and moments.

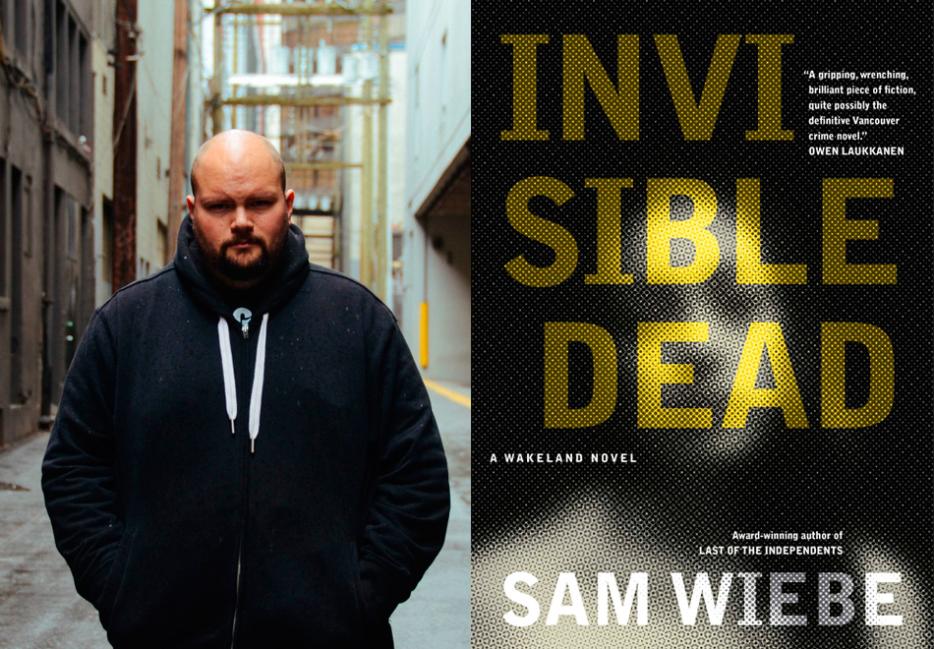

Sam Wiebe has deep Vancouver roots, and has been writing and teaching college in and around the city for years. He took the Kobo Emerging Writers prize for his first, standalone mystery, Last of the Independents, generating interest in this, his first series character, before he’d completed his final draft. Wiebe starts his new book with a phrase that combines despair and a disclaimer: “I don’t know why this city sees fit to kill its women. Answers won’t be forthcoming.”

Naben Ruthnum: You're writing about a vanished First Nations sex worker in a Vancouver setting, which sets off a lot of associations all at once: you’re in the territory of real, distressing, recent and ongoing crimes. Did you consider shifting locations? Or having your disappeared victim character have a less charged identity?

Sam Wiebe: I never considered moving the story from Vancouver—I think it had to be set here. Likewise, it had to deal with First Nations and our colonial legacy.

I started writing the book during the Oppal Commission hearings [The 2010–2012 Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, led by former BC Supreme Court Judge Wally Oppal, called the police investigations into the disappearances of Downtown Eastside women during serial killer Robert Pickton’s years of murder “blatant failures” with “recurring patterns of error”] and everyone I interviewed, from sex trade workers to prison guards, said the real story wasn't coming out—that there was a narrative being formed of, "Well, it took us a while, and the system sure isn't perfect, but in the end we caught our man."

So it was important to me to start with the assertion that we don't know. That not only do we not know the answers, we haven't even started asking the right questions.

You're writing about different kinds of poor people and people who got wealthy in different ways. We meet both biker-gang and real estate millionaires in these pages. I guess this type of class and wealth mix just happens when you're writing about modern adults, but did you have a particularly Vancouver-specific lens on class that you were working with here?

Vancouver is in upheaval right now due to the real estate crisis—though really there are real estate crises. The housing shortage for young educated professionals in their 20s and 30s isn't the same as what affects homeless or low income people.

So that shapes my depiction of the city. The neighborhood where I grew up, where my grandparents bought their home, now every house has been subdivided into suites, and there're a lot fewer families. Parts of the city, like False Creek, are unrecognizable.

It's no surprise to me to learn that you have generational roots in Vancouver, because there’s a depth to your depiction that is pretty rare in books about the city. I lived there for years and end up explaining to people out east that the West Coast student life or tech-guy angle that represents Vancouver on the internet isn't nearly the whole story, nor is what they read about real estate or crime out there. One thing that I think Vancouver has, in a big way, is an expertise in looking-away, particularly in the Downtown Eastside.

"An expertise in looking away" is an excellent way of putting it. Vancouver has some of the most diligent social workers and volunteers in the world, but there's a precariousness to their work because of that looking away—the Insite facility [a safe-injection site in the Downtown Eastside] always seems one political shift away from being shut down.

There are very complicated ways that business, addiction, the sex trade and colonialism [in Vancouver] intersect, and I'm not the best person to speak to that. But I think it starts with education. As a product of the BC school system, I didn't learn anything about indigenous cultures until third year of college. So if that ignorance holds true for others, what else are we ignorant of?

This book is so crammed with real Vancouver locations that I had to wonder why you changed names of venues when you did. Why, for example, is the Cambie the Cambridge in here, when bars and restaurants such as Malone's and Peckinpah's go by their real names?

I changed venue names when the venue was used in the story for criminal or disreputable activity, or insinuated to be owned by a criminal organization. Basically I didn't want to get sued.

The point in the novel when your detective, Dave Wakeland, buys a gun gave me pause. Is it really this easy to buy a handgun in BC?

Buying a gun is pretty straightforward once you have your PAL [firearms license]. For a pistol you need to wait for an ATT [authorization to transport], which can be approved in twenty minutes or a couple weeks depending on how busy the office is. Getting a license in Canada is difficult, but buying a gun is easy.

You have Dave Wakeland observe that William Gibson gave us a more realistic depiction of Vancouver with the "Japanese sprawls" in his early novels than any other author did. I couldn't help seeing this observation as a challenge to yourself: what kind of justice did you want to do to the city?

What makes Vancouver so fascinating is that its future is so uncertain. We're a colonial outpost on unceded First Nations territory with one of the largest Asian populations in North America. It can be hard to wrap your head around it, but it's also very liberating for a writer.

My favorite Gibson story, by the way, is "Winter Market," one of the few things he wrote set in Vancouver. He really captures the feeling of being overloaded by culture and technology.

I caught some of Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep in Wakeland's initial meeting with the vanished Chelsea Loam's mother, his client. Wakeland's knight-errant ethos is reminiscent of John D. MacDonald’s series character Travis McGee. And your prose here and there, as well as some of Wakeland’s morning routines, reminded me of the books featuring Dave Robicheaux, James Lee Burke's detective. Of course, it's no coincidence that those are the detectives I've been reading the most of in the past little while. Who are the series characters that you took a cue from?

I haven't read as much of Burke's work as I should. Peggy Blair recently told me I have to read him, so he's on my TBR pile. Right now I'm a big fan of Peter Temple's Jack Irish series, the Dublin Murder Squad novels by Tana French, and Qiu Xiaolong's Inspector Chen series—my students loved his novels set in Shanghai.

What do you want to resist in your writing, as you continue the Wakeland series? Are there pitfalls, traps, that series detective writers face?

So many series characters are author wish fulfillment. I think that's something I wanted to avoid. Dave isn't invincible and he's not always right. He definitely doesn't have a big tough crazy best friend to bail him out of situations.

I've been rereading Ross MacDonald's Lew Archer novels, and what I like about them is that they're less about resolution than revelation. Archer loses more fistfights and gun battles than he wins, and if he's heroic it's because he's willing to pay the psychic cost to get to the truth. I think that's a better definition of heroism than just making someone the toughest and strongest and the best at violence.