He was a freaky something else, a gift from another world. Prince Rogers Nelson was the blueprint for shady Black femmeness: a master of weaponized side-eye for any occasion, quick with the seeming compliment that morphs into a slow-detonating insult. He taught me these things.

It’s easy to take the liberty of assuming that he—“not a woman, not a man”—was deeply queer, and not just in the way his public persona was deployed. In truth, there wasn’t much distinction between Prince’s “public” and “private” selves. That’s radical. His experiences became the fuel driving his music. For us, it was the reverse: our experiences were driven by his music and his creative genius. It feels as though everything anyone could say about Prince has already been said. In the wake of his death, the world has revealed—via a critical mass of thinkpieces—just how much love we had for him.

In the interstitial spaces of my life, Prince has kept me company. In the volatile moment, full of change—in the moment that would give me pause in my sureness and sense of self—he was there as if to say, “Relax, baby you got it.” In the time between middle and high school, my great girlhood becoming, Prince was there.

*

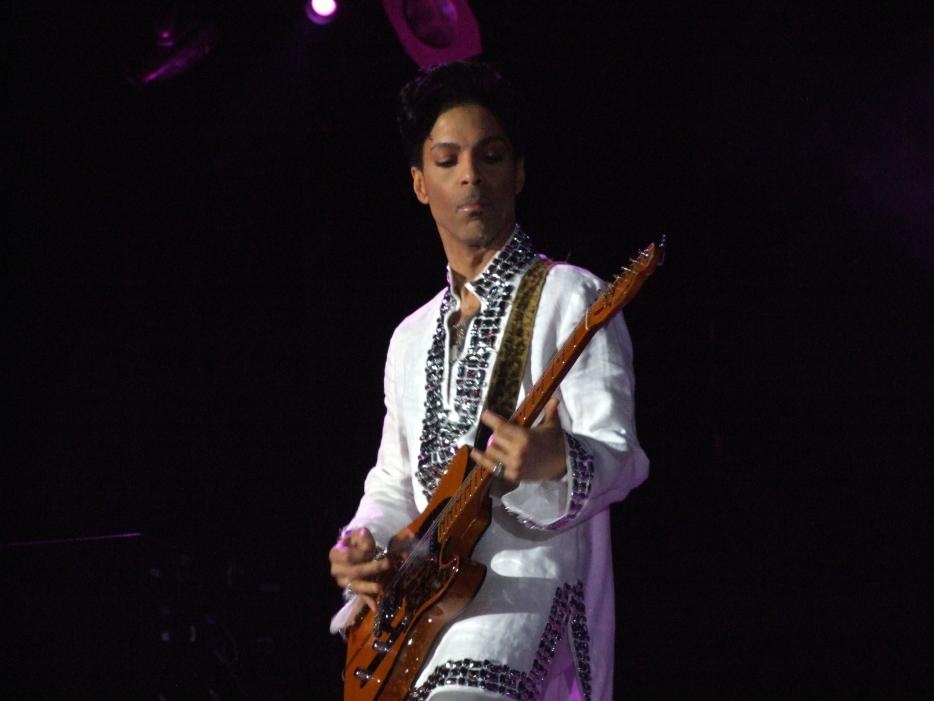

What was it about the way he fingered the guitar? His sexy-as-fuck stage presence indicated that he enjoyed a virtuoso status beyond music. To be clear: he really, really, seemed like he was good at sex.

A virtuoso must possess a certain flexibility of both body and mind. The degree of facility—maybe intimacy is a better word—with different instruments and musical genres that Prince attained in his lifetime required finesse. Just think how well he knew the contours of not only his own sound, but the sound of artists like The Bangles, Sinead O’Connor, Madonna, Kate Bush all of whom he crafted definitive hits for. So many of our beloved female pop stars from the 1980s touched up against Prince’s sound. There’s something so sexy about the range of conceptual movement that marks a career of prolific collaboration.

Born a black boy from Minnesota, Prince understood that for some of us, a certain flexibility in the face of rigid structures is necessary to survive. But he had a fire inside of him too, something that burned too hot to be contained by industry executives or aesthetic stasis. He was a perfectionist, an anxious control freak in only the way a virtuoso can be (the way someone is when they actually are better at every aspect of creating music than everyone around them).

*

When I came out and had to then figure out who I was trying to be, Prince helped me make a self, something else he was very good at. He made and remade himself. He gave birth to himself; he was his own mother. When I think of the question lingering in the pop culture imaginary when it comes to Prince, I think of his notorious name change. Here, a transformation from a name that could be uttered to an unspeakable symbol. Why did Prince try to escape his name, the one signification of self that is cursorily recognized? Was it an attempt to buck categories and definition altogether? His attempt to push his own artistry beyond the confines of an established brand? A PR stunt? Was he fed up with his slave name and the history behind it? Was it an attempt to escape legibility altogether? As if to say: “You think you know me, but you don’t?”

People watched him, and they thought they knew him because they loved to watch him. He was always aware of the cameras, making dramatic eye contact and inviting the lens seductively into the party. Tiny, elegant, adorned, and too full of feeling and genius not to let it come gushing out, he was, as my friend and poet Jasmine Gibson says, “a femme root” and a way to ground ourselves in a world of constant upheaval as queer black people. He let us know that though we were not virtuosos, we too could finesse our way to where we needed to be.