“Choose life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family.” These are profoundly ordinary phrases on their own. They are not clever or directive enough to be fashioned into word art for a Pinterest board, not sweet enough for a refrigerator magnet. But these basic commands have taken on meaning greater than the sum of their parts since they opened 1996’s film adaptation of Irvine Welsh’s novel, Trainspotting, the instant classic telling the story of a young man named Mark Renton’s attempts to escape the crippling monotony of both heroin addiction and his own tedious collection of friends.

Most people familiar with the monologue that opens the film are only able to recite these four sentences before the rest of the directives become a hazy litany of things one ought to choose for a full life. The less-remembered choices include consumer items such as “electrical tin can openers,” “leisure wear and matching luggage,” and “a fucking big television,” alongside the more grim expectations to surrender to junk food and mortality as your children outgrow interest and empathy in you. If one is at all inclined to consider alternatives to massive consumption as its own good end, Trainspotting is as much about an economic counter-culture as a drug counter-culture. But this and many of the more revolutionary aspects of Trainspotting hide in plain sight, overlooked by even the film’s most effusive critics and not often dwelled on by its creators. The monologue actually makes a great case for heroin from the get-go: Before anyone has had a chance to describe the drug’s euphoric effects, audiences are already rooting against the rotten core of the consumer society that rejects these affable junkies.

The novel was set solidly in the 1980s Thatcher administration but the fashion and décor of the film blend ‘70s glam, ‘80s punk, and ‘90s Britpop for a stylized effect that suggests that they occupy the country of Cool, a nation that does not recognize the rule of our tiresome Roman calendars.

In our cultural memory, the monologue became a stand-in for all of the joys Renton opted out of after choosing to use heroin instead. But a closer examination of these words twenty years after the film’s debut make it clear that, in his own way, Renton was choosing life—it was just a life that many film critics and a morally panicked public were unable to see as anything but degenerate and filthy. Degenerate filth beautifully executed for cinema, of course, but degeneracy and filth nonetheless.

*

The outcast status of Renton’s crew is made more pointed by how Trainspotting exists somewhere just outside of time. The novel was set solidly in the 1980s Thatcher administration, but the fashion and décor of the film blend ‘70s glam, ‘80s punk, and ‘90s Britpop for a stylized effect that suggests they occupy the country of Cool, a nation that does not recognize the rule of our tiresome Roman calendars. Fifteen years after the film’s release, star Ewan McGregor told Clash Music, “In the book, you didn’t want to put it down because you wanted to be in amongst these people—when in actual fact if you met these people it’d be a nightmare—and I think that’s kind of what we achieved with the film.” For loads of young people, McGregor and co. were an enviable squad of ne’er-do-wells.

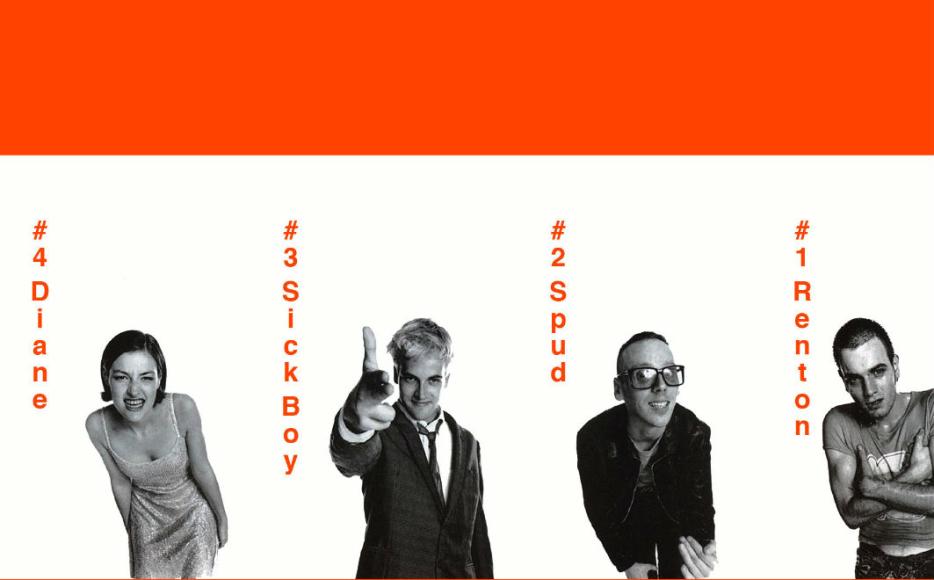

Trainspotting’s gleefully degenerate cast of characters were designed to be admired from the beginning: the advertising campaigns for the film showed cast members photographed in black and white standing on white backdrops with names like “Renton,” “Sick Boy,” and “Spud” in orange text. The result was more boy band than bad boy, a slick way of marketing these characters so that girls might pick their favorites the way they did the Spice Girl to whom they most related. They had interests well beyond the supposedly toxic biomes of their drug basecamps. The flat in which they shoot up is not especially filthy and is even vibrantly painted. They casually worship Iggy Pop, hit on girls at clubs, and keep company with morally bankrupt friends because it is often easier to tolerate sociopaths than to escape them. These were not just people, they were people with attitude, moxie, a swagger loaned to them by poverty, bored masculinity, and intravenous opiate doses.

*

Even the most glowing reviews of Trainspotting read like the critical equivalent of a parent scolding a child for misbehavior that’s ended in comic results: they want to remain firm in their moral point but can’t help laughing at the delight of the scene. “The perversely irresistible ‘Trainspotting’ is itself geared to the tourist trade, since it keeps a safely voyeuristic distance from the real dangers that go with its subject matter,” wrote Janet Maslin in the New York Times review. Anticipating the slew of pieces that would wag a finger at the lack of moralizing or dreary ends, director Danny Boyle told Fiona Russell-Powell in Dazed and Confused’s March 1996 issue, “All you can ever do is tell the truth and you should say the reason why people do heroin is because, actually, it makes you feel fucking wonderful." Roger Ebert gave the most reliably nuanced review of the film, calling it “pragmatic” because, “It knows that addiction leads to an unmanageable, exhausting, intensely uncomfortable daily routine, and it knows that only two things make it bearable: a supply of the drug of choice, and the understanding of fellow addicts.” But this assessment too flattens the dimensions of these characters and the lived realities of those on whom the film is based.

One can reliably assume that in any work of art portraying heroin use, the introduction of an innocent will function as a sort of Chekhov’s gun: if an animal or infant is alive and accounted for in the first act, it will reliably be killed by the heroin users before the credits roll.

In all the literature about Trainspotting’s portrayal of heroin use, there is a blinding absence of actual heroin users offering their expertise on what it means to make the choice at the core of the film. I found that expertise in Caty Simon, the editor of sex worker-owned and operated website Tits & Sass, who writes candidly about the portrayal of heroin use in media in contrast to her own heroin use and that of those around her. She recalls relating to the monologue then and now, saying, “The long-term rewards of buying into capitalism and a straight life, it is just so absurd when you actually see it that way. Sure, we are paying through the nose for our survival and pleasure, and the constant, tiresome routine of the dope world, that sucks too. But their world looks so alien to me. How do people kid themselves into believing this is worth it? Looking at what other people do, looking at what we are supposed to choose instead, I can’t imagine choosing it.” But in the public imagination, heroin users are rarely humans making choices—they're one-dimensional avatars for irredeemably selfish vice.

Deficits in their own earning power and sexual prowess render these characters idle, but the exchanges we witness disclose enduring friendships that have more to them than shared addiction. “There is an idea that we have a monomaniacal fixation on the dope, but it really is a boring quotidian afternoon with anybody else. People are going to be shooting speedballs and talking about their favorite movies,” Simon told me. “We are usually navigating the mainstream world with everyone else.”

On the subject of disgust, despite the slick marketing of the film, Trainspotting has its fair share of absolutely repulsive, cringe-inducing moments, particularly for a movie that gained such mainstream acclaim. A baby named Dawn dies and then rots for a while and, if that wasn’t enough, reappears in the third act to crawl across a ceiling, turn its head complete around a la The Exorcist to terrorize Renton in the thick of heroin withdrawal. (One can reliably assume that in any work of art portraying heroin use, the introduction of an innocent will function as a sort of Chekhov’s gun: if an animal or infant is alive and accounted for in the first act, it will reliably be killed by the heroin users before the credits roll.) Renton dives deep into a heap of diarrhea and likely more unspeakable sludge in what is cheekily referred to in an on-screen caption as “The Worst Toilet in Scotland.” His lovable compatriot, Spud, shits himself at his girlfriend’s house and, in a mishap that nightmares are made of, accidentally sprays his accident all over her family at the breakfast table. But beyond the shock value of the more putrid elements of doing heroin, the depictions are an objectifying and othering tactic that dehumanized heroin users. “I didn’t appreciate having our bodies reduced to these dirty vessels that excrete shit and vomit whenever we’re not shooting up,” said Simon.

Trainspotting has been identified on more than one occasion as the cinematic representative of Cool Brittania or Britpop, the phenomenon of post-Thatcher Britain being shook alive by music and cinema that originated in the working class and ascending quickly to Supernova Heights. Much like the ethic and ethos of Cool Brittania, this stylish little film about a bored group of friends who happen to be junkies outgrew itself when it was designated as heir to the throne of Cool. The media’s penchant for looking for holes in moral narrative arcs averted our eyes from the more subtle tragedies the film portrayed perfectly. In particular, the grisly decision by Renton to choose that simulacrum of the good life at the film’s end, abandoning his friends for consumer culture and an opportunity to purchase distractions to mortality until death comes for him—a degenerate way of life if there ever was one.