On the coldest days we gathered around Flickr. The account wasn’t ours—my theory was it belonged to a teacher, almost certainly an expat—but its contents were: pictures of Kuwait, the country of my birth, taken in the 1980s, and a time before Canada and the frigid rake of the Atlantic Ocean stole the spark from my parents that once said, We are cosmopolitan thirty-somethings, proud stewards of the world. We were hypnotized. There was a bulky, beige monitor not 10 centimetres from us, but it would break your heart to see it from our eyes. The account is long gone, or there but less relevant to Flickr’s search, so, gone.

This is a footnote in the continuum of the immigrant’s dilemma. To don the suit of a past life and know it is fully, utterly annihilated. Or worse, to see in your parents something you can’t quite figure out, despite your age being close to theirs, back then, in the country they left behind. Even by choice, it feels like a theft.

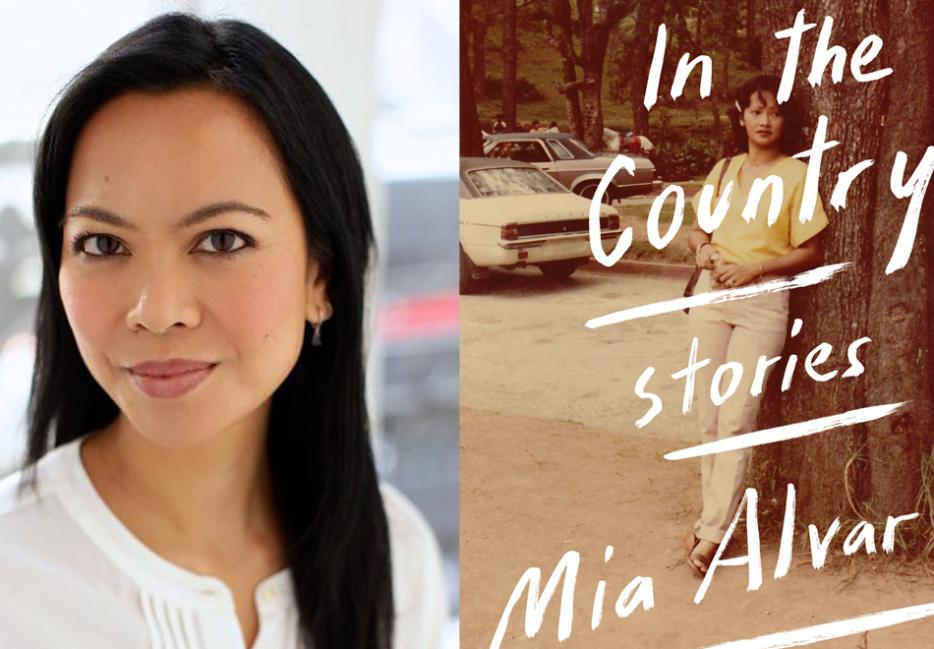

In the Country is Mia Alvar’s fiction debut, a collection of nine short stories exploring the weft and weave of the Filipino immigrant experience, as people across the nation attempt new lives in the Middle East, and, eventually, beyond.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of cherishing a book because the author shares aspects of your own story. Both Alvar and I lived in the region at roughly the same time, Alvar having moved to Bahrain at a very early age, a few years before I was born. Both of us lived comfortably as part of an emerging middle-class. Both of us, while ethnically divergent as possible, were, in the eyes of the Arab majority, simply “brown” and treated as such. I could string the dots for hours, but the similarities do nothing to dull Alvar’s prose; the way she inhabits characters much like my parents, if slightly different; the observations that laid bare the politics of a country with infinity money, and its effects on the guest workers making a go at it.

Truth be told, In the Country was the first time a book spoke to my own lived experience, in ways the words of other Indian immigrants hadn’t. The first time anything reminded me of that damn Flickr.

Alvar visited me at the offices of Penguin Random House Canada where we discussed Filipino customs of death, family obligations, and interior decorating, of a kind.

*

Anshuman Iddamsetty: I understand fiction was the last thing on your mind.

Mia Alvar: I didn’t know I wanted to write fiction until my senior year in college. Before that, I really thought I was going to be a poet. It’s funny, I took poetry workshops with a lot of people who said that they came to poetry in the opposite way: They were fiction writers and over the years their thinking became less linear, less narrative. It was the opposite for me.

So your thoughts were more … snapping into place?

Yes. I visited the Philippines for the first time in 1998, after being away for ten years. My grandmother was sick and dying, and I didn’t intend to make fiction out of that experience, but I had a notebook with me and found myself recording the images that were so arresting after being away for so long.

What kinds of images?

Death and preparing for death, and dealing with the rituals afterwards. So on the one hand, I had all these experiences that I didn’t know what to do with yet, but they wouldn’t leave me alone. I started to think of my family experiences and childhood memories as material for the first time. In some ways fiction provided some protection as well. It felt a little too raw, too personal to say, “This is what happened to me.”

Right, especially when death is the entire reason you return. Curiosity, I find, is a good cover for grief.

Yeah. Yeah. When I went back for my grandmother, I was really interested with what happened immediately after she officially passed away. There’s this avenue in the Philippines that’s essentially a business district for the business of … death. So all of your funeral needs, from flowers to cremation to urns to headstones, can be serviced in this one avenue. I was kind of like, “I can’t not use that somewhere!” Also, just how much of the process of getting her ready for burial was open to us. We were down in the basement of the funeral home when the mortician was doing her make-up. I think an editor flagged this for fact-checking: “I’m pretty sure you wouldn’t be allowed down there.” [Laughs] And yet we were, and I don’t know if that was some sort of privileged thing—my mother flashed her American dollars and they said, “Okay”—or if that was just normal. All of that was hard to forget.

Did you ever feel obligated to police your observations? To keep yourself from recording everything?

I didn’t feel obligated to leave things out or not use certain experiences. I mean, certain people in my family would recognize the inspiration and what would be fictionalized in the intervening years. My family is also … they’re a very cheerful people without self-esteem problems. They read everything through this lens that allows them to see In The Country as a tribute, no matter what. Oh, it’s a story about family! And having a party and karaoke and food! We do that! Therefore it’s a celebration of that and of us!

Almost the opposite of what many memoir writers struggle with.

Yeah, even when they change all sorts of details they still make people angry.

I imagine it’s kind of affirming, to see themselves there, on the page, in full.

I hope that that’s part of it. Obviously, one of the most powerful reasons to read fiction is to read about an experience that’s completely different from yours. Probably the most important reason—among many. There was a time when I was really looking for myself in fiction and sometimes having to do a lot of digging to find short stories about young girls who grew up Filipino and Catholic contending with American influences in a new country. And yeah, I think it’s powerful and affirming to see someone who looks like “you,” on the page. The way it is to encounter that same person in real life.

“Encounter.” I like that word. It reminds me how talking about the immigrant experience—to a stranger, at least—is not unlike science fiction.

I think in some ways that’s the perfect analogy. Obviously not the genre I’m writing in, for sure, but science fiction is dramatizing so many of the same things. Being dropped in completely unfamiliar worlds, having to learn all sorts of new codes and languages and behaviours, and just having to figure out this brand new terrain. I enjoy it when writers are able to do that. I saw this awesome edition of This is How You Lose Her on my way to the bathroom. Of course, Junot Diaz did it so beautifully and intelligently with The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

I think that’s why I took to In the Country. The resonance I felt with you dramatizing life of non-white, non-European immigrants. Your Bahrain could’ve been my Kuwait.

I was six years old, so that would’ve been ’84. I remember it so much more vividly than the Philippines because I was so young when I lived there. My memory of the place is this multicultural utopia because I knew I was playing with kids from all different countries and hearing all kinds of languages around me, even though we went to an all American school. It was a very kind of idyllically international experience in some ways, but kind of compartmentalized in other ways.

Your parents …

… only socialized with other Filipinos, yeah. We were not required to learn Arabic, which I regret all these many years later. There was a lot of intercultural dialogue and mixing, but also a lot of separation, and a very different—I think this is very true of overseas Filipino workers and contract workers who go there now—a very different kind of experience from immigration to the U.S. or to Canada, I think.

Yeah, none of the adults talked about Kuwait being it, either.

There’s a very solid concept of, like, “I’m coming here and I put down roots here and become a Canadian and become an American.” I’ve never heard a Filipino say, I’m going to become a Bahraini or a Saudi. It’s this idea, this kind of waystation—where people are biding their time and saving their money before they return home, sometimes after many decades in some cases. Or sort of hanging out until the next permanent place.

For many immigrants—not all—there’s the sense that once you’re “here,” that’s it. There’s no going home.

Isn’t that fascinating to you? Of course there are practical reasons; It’s a much longer trip, much more expensive. But I do think without some sort of mental conceptual shift that wouldn’t be true. I’m so interested in why one place was home and the other place wasn’t.

Any theories on that shift?

I think it has to do with the concept of there being an American identity you can at least, theoretically, legally, adopt.

You could be naturalized.

There’s no history of that in the Middle East. I think it probably has to do with, at least in our case, Americans and our relationship with work. Like, there’s no such thing as a three-month visit back home. Work is so much a part of your identity, to leave it—to kind of cultivate this other part of your identity—is unthinkable. Certainly was to my mother, once we moved to the States.

Many of your stories explore the unspoken class divisions in the Bahraini workforce. It was the same in Kuwait: First came the Arabs, then white people, and below it all, us—black and brown people, lumped together. I couldn’t shake the weirdness of being part of a brown family living comfortably among the Arabs because my dad happened to study chemical engineering. We were protected, sort of.

Oh, there’s so much there, and part of the reason I wrote the story “Shadow Families,” was to articulate that distinction. When I mention that my family is Filipino and we lived in the Middle East, those who have a tiny bit of experience will say something like, “Oh yes, there are so many Filipinos in the Middle East,” and their minds will immediately go to the person who takes care of their elderly grandmother, or a domestic worker that they knew. Like you said, my family was sort of protected from a lot of those blue-collar experiences by my father working a white-collar profession. I’m fascinated by how those two groups become socially one group in the Middle East, to some extent. The Bahraini were considered the true upper class. Filipina women who would’ve employed certain other Filipina women back in Manila would be mutually homesick friends in Bahrain. “Shadow Families” was my way of looking at that bonding experience and the differences and tensions that can’t be elided by the two experiences.

I also remember the comical opulence of life as a white-collar, middle-class expat. Black and gold. Wall-to-wall marble.

[Laughs] Right?! I love that phrase “comical opulence” because it really is this aesthetic that’s very specific to the company-provided house. Also, the experience of moving into a house that has been outfitted for you and will look the same for the next family that moves in … it’s just fascinating to me. I don’t even know what to do with that experience other than describe it. These are certainly not things my parents would’ve chosen for themselves. It was an alien aesthetic from what came before and would come after.

Another aspect that resonated with me was the care packages your family would send back home to the Philippines, the balikbayan. My parents still send money to relatives I haven’t seen for almost two decades.

I’m still amazed we took apples in a suitcase. It’s strange. You think you’re providing these amazing things to the people back home, and in some cases it’s not quite in the form of what they most want or need.

How do you mean?

I remember my mother going through her personal effects, trying to decide what would go to whom and talking about how she would send my grandmother so much jewelry. But after her death, she couldn’t find any of it. She concluded that her mother must’ve pawned it all—when she needed to. It was funny. It also made a ton of sense: When you couldn’t meet a basic bill, why would you need a 24-carat gold crucifix around your neck?

Sending things back also felt like a reminder of our status as immigrants. Family was just another thing we lost.

There’s also language. I’ve improved my Tagalog over the years because I actually made a point to study it formally. Unless you have it around you all day, every day, there are still conversations with the family that go too fast and go over my head. There are idiomatic expressions that don’t roll off my tongue, there’s a lot of wordplay between Tagalog and English because there was a strong American presence for so long. And I cherish it, all the punning and the raw fun they have mixing the two languages, but I know 75 percent goes over my head. That’s a big hole migration created, and impossible to recover. No matter how much I study, or visit.

You sound envious.

I do think there’s a certain… not envy, but wistfulness I feel for the kind of skills and sense my parents grew up with that I didn’t have because they protected me from having to need them! [Laughs] The survival instinct in my parents and the generation before them. There are times when I feel ill-equipped for everyday life in comparison to how equipped they had to be at such a young age.