Cara Jeiven was at a drop-in session at a kids’ gymnastics gym in Brooklyn, watching as the manager taught Jeiven’s daughter, Hannah,* how to do a flip on the uneven bars. The woman had the intensity of a reality TV dance mom. “Show Mommy how you do it,” she repeated as Hannah practiced. “Show Mommy how you do it.” Hannah looked around, confused. Her mommy wasn’t there.

Jeiven approached the manager and explained that while she is Hannah’s parent, she goes by a different term. Her wife is “mommy,” and Jeiven is “baba.” The woman laughed and called her own daughter over. “You're never gonna believe this,” she told her. “This kid's mom is called ‘baba.’ Isn't that weird? You call my breasts ‘babas.’”

She persisted in calling Jeiven “mommy.”

Jeiven is one of a growing number of genderqueer, butch, two-spirit, and trans parents who are raising children outside of the rigid binary of “mother” and “father.” In North America, in just the last few years, a more nuanced and complex set of gender identities have achieved mainstream visibility, through fights for legal protection and access to medical care, and growing media acceptance of public figures like Janet Mock, Laverne Cox, and Chelsea Manning. The difference between the reception of Chaz Bono, who came out in 2009, and Caitlyn Jenner, who came out in 2015, speaks volumes—questions and assumptions that would have been a matter of course six years ago are, today, recognized as invasive and besides the point (even as they are still asked and made—lookin’ at you, Katie Couric).

In progressive circles and on university campuses, it’s becoming increasingly common to ask individuals for their preferred pronoun as part of an introduction; conversely, parents—even queer and same sex ones—are routinely read as “mom” or “dad,” with all of the attendant expectations of femininity and masculinity. For decades, queer activists and gender studies scholars have worked to divorce gender and sexual identity. Now, interest has turned to divorcing parenting roles from gender and placing them on their own independent axis—gender, sexuality, and parenting intersect and affect one another, but have no essential, deterministic relationships.

The invisibility and dysphoria of masculine pregnancy has cultural, not physical roots. We’ve conflated sexed reproduction with gendered cultural attitudes towards pregnancy and lactation, reducing pregnant and breastfeeding bodies to feminized “goddesses”—to be judged, revered, and not materially supported (as seen in the pushback against public child care, subsidized food programs, and parental leave). These attitudes are injurious to feminine gestational parents and wholly exclusionary of masculine ones.

Thankfully, the meanings we’ve attached to the pregnant body aren’t fixed. It takes a sperm and an egg to create an embryo, but it doesn’t necessarily take a masculine man and a feminine woman, or a man and a woman at all.

*

Karl Surkan, a women and gender studies researcher, identifies on the transmasculine spectrum while “floating between different social identities.” Surkan was the gestational parent of his son—he carried and gave birth to him—and he goes by “papa.”

For Surkan, the health care system is often the site of the kind of confusion Jeiven experienced at the kids’ gym. Surkan and his partner were read as a lesbian couple at their Massachusetts fertility clinic. Same-sex marriage had just been legalized state-wide, so he felt like their appearance made a sort of basic sense to the nurses and other patients. Surkan’s feminine partner was often wrongly assumed to be the patient. He finds that people particularly struggle with the idea of referring to gestational parents by masculine terms. “When my children were very young and I was breastfeeding, the idea that I was papa was not understood by anyone, in particular by caregivers or pediatricians. I would take my son to the doctor for a check-up and they would say, ‘You can sit on your mom’s lap.’ And my son’s looking all around, and thinking, ‘She’s not even here. How can I sit on her lap?’ Because I, of course, am not the mom.”

Pregnancy, Surkan points out, transforms the body in ways diametrically opposed to our society’s very narrow view of what a woman should look like, and how much space she should take up. Because of this, “There’s a huge need to shore up women’s sense of femininity. And so the way to do that, culturally, is to say: this is quintessentially the most feminine thing one can ever do.” This often results in the misconception that one can be pregnant or masculine but not both, rendering the pregnancies of butch women and trans men invisible. Surkan wrote a paper titled “That Fat Man is Giving Birth” about this false dichotomy. While pregnant, he opted for overalls, button-downs and oversized men’s shirts—the maternity section carried “nothing [he] would be caught dead wearing.” He adds, “You would think it just needs to be cut to accommodate this growing belly that you have, but they have to slap a bunch of lace or feathers on it, or this weird shelf thing so that it highlights your breasts. I’m not going to wear anything like this. This is probably what happens to a lot of people.”

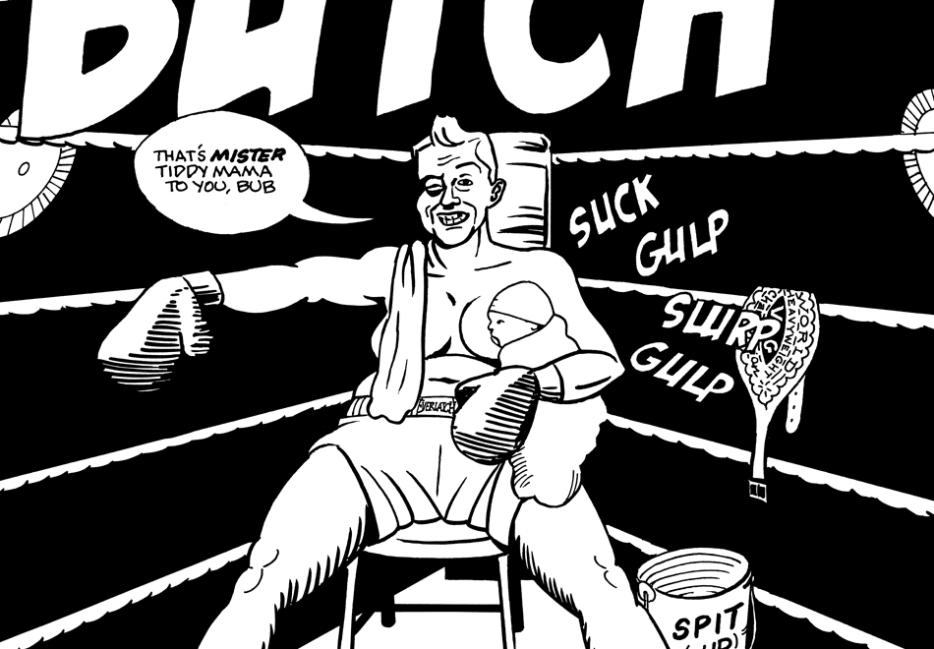

For those of us who’ve experienced gender dysphoria, and spent time carving out an identity and presentation in the world that allows us to be comfortable—and, hopefully, recognized for who we are—pregnancy can feel especially fraught and alien. A.K. Summers subtitled her graphic memoir Pregnant Butch “Nine Long Months Spent in Drag.” In an interview, Summers told us that throughout her pregnancy, “I was really concerned about losing myself, losing my gender identity, my sexual identity.”

Pregnant Butch opens with Summers on the New York City subway in a short-sleeved, button-up T-shirt, standing against a pole between two seated men. “New York is not known for its gallantry where pregnant women are concerned,” she explains. “So imagine how often you’re offered a seat when most people take you for just another fat guy on the subway.” On the next page, Summers draws her pre-pregnancy fantasies: maybe her pregnant belly will resemble a dude’s hardened beer gut, and she’ll be able to pull off period Western garb, berets with trench coats, and suspenders. Pregnancy, however, does not bestow the “broad shoulders, slender hips, and titlessness” of her imagination; she gets her suspenders, but they’re holding up billowing “clown pants.”

Summers’ candid, corporeal depiction of pregnancy resonated with a wide swath of readers. “Quite a few straight women,” Summers says, “responded to [Pregnant Butch] with, ‘I am so sick of yoga-mommy-bliss prescriptions, and how this is supposed to be this amazing, apex of femininity experience, and that’s not how I feel.’”

Pregnant Butch was initially serialized as a web comic. Before the completed memoir was published in 2014, Summers rejected the suggestion that she should consider other titles. She was proved right: “pregnant butch” turned out to be a popular search term, as more and more people sought alternative models for pregnancy.

In gender and culture theorist Jack Halberstam’s book Gaga Feminism, he points out that children are more accepting and often simply care less than adults about how others identify. This flies in the face of the conservative argument that non-binary and genderqueer people are “confusing,” or even somehow threatening, to children. With his partner’s children and their friends, he says, “There would often be a short conversation: Are you a boy or a girl? Oh, you’re a boy. Can I call you ‘he’? Yes. But you kind of look like a girl, right? Yeah, kind of, sometimes, but I’m a sort of in-betweener. Oh, okay. And then onward. Not tons of curiosity. No judgment.”

*

Andrea Lawlor, another baba, never had any interest in carrying a child. “Even though I know plenty of butch or even transmasculine parents who had, that was something completely dysphoric and weird and not interesting to me.” If her partner hadn’t been able to conceive, they would have adopted.

Lawlor had been thinking about transitioning for at least twenty years, but parenthood brought the decision to the forefront. “I thought about it a little more seriously. Would it just be easier to really inhabit a dad role, visibly, in the world? And have that be more simple-seeming? Obviously not actually more simple.”

Many prospective parents who were comfortable existing in an in-between space, with fluid or nonspecific labels, feel like it’s necessary to “pick a side” when facing parenthood. Before settling on baba, Cara Jeiven, like Lawlor, felt pressured to solidify her gender identity. “I knew I didn’t feel like a ‘mother’ and didn’t necessarily want to be a ‘dad,’” she says. “I suddenly felt like I had to choose.”

“When you’re looking to egalitarianize things across gender, or race, or culture, or whatever, the experiences of the non-privileged group tend to get flattened out or erased.”

Lee (who requested we not use his last name), a transman and adoptive single father by choice, said planning for parenthood was one of several factors that led to simplifying the more complex identity he had in college. “I see a lot of awesome people, a lot of whom are younger than me, in environments like Tumblr, exploring gender in a really exciting way, but also a really exhausting way.” When Lee was twenty and non-binary identified, he met a trans guy who was thirty. “I’d been using lots of different pronouns,” he recalls, “and all that type of stuff. And he was like, ‘You’ll get older and this will become too much.’ And I was like, ‘No! Never!’”

While Lee doesn’t want to invalidate his past or the experiences of others, he eventually felt the need to free up the mental bandwidth he’d once allotted for questions of gender performance in order to worry about his kid, his job, and his rent. “Particularly with parenthood,” he says, “there’s a decentering of self in a really profound way. We end up getting to be more simplified versions of ourselves, for better and for worse.”

According to Halberstam, this pressure to stabilize and normalize is not unique to queer and gender non-conforming parents. “All people become more normative when they parent,” he says. “And they do so under the pressure and the scrutiny of schools on the one hand and other parents on the other. Children are not the vectors of normalization. They are just the occasion for it.”

*

People who have rejected heteronormative gender roles in their individual lives and relationships necessarily consider the gendered workload of parenting with greater scrutiny and awareness. Many raised the issue of how masculine parents—cisgender men, transmen, butch women—still aren’t expected to take as active a role in parenting as feminine parents.

While Lee was riding a city bus in Boston with his son, a stranger once sat down beside them and said, “Oh, isn’t it great that you’re having a daddy day?”

Lee replied, “Well, every day is daddy day. I’m a single parent.” The woman responded effusively, telling Lee that what he was doing was “wonderful.” Noting that Lee is a transracial adoptive parent, the woman congratulated Lee on “saving” his son.

“I can look into his eyes and see that he's come from a hard situation,” she said.

Lee responded politely but was inwardly eager to reach his stop. “It was kind of two things piled on top of each other,” he says. “The adoption saviour thing, and the ridiculous kudos you get for doing basic parenting when you're male-presenting."

Andrea Lawlor agrees. “I hear from a lot of dads I know,” she says, “and I’ve experienced it to some extent—that thing where a dad will walk around with a kid and get all this praise and also unsolicited advice that’s really condescending. ‘Oh my god, you’re a hero,’ for walking down the street with your kid.”

Just as pregnancy is regarded as inherently tied to womanhood, so is the daily nurturing that raising small children requires. Lee points out, “Being a primary caregiver and being male identified, even for straight dudes, even if you are in a heterosexual partnership—there is a queerness to that in our culture.”

“You have to be really secure in where you’re coming from,” says Lee. “That can be much harder for transmasculine people than for people who have had their gender identity be stable. You have to let go of, ‘Oh god, someone’s going to see through. I must really be a girl because I’m doing these feminine things.’”

Furthermore, low expectations for fathers have persisted for so long that it’s often difficult to find involved, masculine role models for parenting. Other babas and butch parents on the Internet helped Lawlor find the language to articulate her role, and helped her feel less alone, but she also looked to the men who surrounded her to establish her parenting style. “Older, straight, cis guys I know who are artists, or progressive, guys who’ve had a lot of therapy, poet dads. Who are the weird parents? Who are both weird and have boundaries? Those are the people I’m trying to find and do what they do.”

Cara Jeiven looked to her own father as a role model: “What I love about my dad is he’s not this manly, manly man. He loves gardening. He loves opera, and he’s just a sweet, gentle guy. And I think to myself, that’s the kind of guy I’d like to be.”

More egalitarian parenting expectations seem like an obvious good, and a natural achievement of long-held feminist goals. But Lee raises a caveat to this blind push for equality. Pregnancy and nursing, he says, are singular experiences, and it’s important to acknowledge the different needs of gestational and non-gestational parents. “When you’re looking to egalitarianize things across gender, or race, or culture, or whatever, the experiences of the non-privileged group tend to get flattened out or erased. ‘We’ll just treat everybody the same, as though they’re like the privileged group.’ I feel like egalitarianizing a lot of parenting stuff ends up erasing women more than it does benefiting them.”

When asked what they’d like to see change, the parents we spoke to echoed the sentiments of most progressive parents, what Lawlor referred to as “basic tenets of feminism”: more independence for children, less helicopter parenting, more structural and economic support for childcare and parental leave, a Scandinavian approach to cross-generational relationships— where parents are less squicky and more realistic about teenagers being teenagers—and, finally, better media representation and more social support options for gender non-conforming parents.

In Pregnant Butch, after A.K. Summers relates an experience with a particularly frustrating, gender-reductive birth education class, she illustrates her “dream class” as a rollicking, supportive, cheerleading pyramid of parents: “There’d be at least one other pregnant butch. And some femme-on-femme, butch-on-butch action. A hot single, bearded lady, some highly idiosyncratic classifications. At least one threesome… reinforcements.”

*

In 1971, the National Organization for Women passed a conference resolution that officially expanded its policies to include lesbian rights. In 1975, they raised $1,000 for the legal fees of Mary Jo Risher. Risher and her female partner both had children from earlier marriages and lived together as a blended family. Risher’s ex-husband had their custody case re-opened when he learned Risher’s sexual orientation. She ultimately lost custody of her nine-year-old son, largely due to the testimony of her seventeen-year-old, who said he was "ashamed of the way she is."

Forty years later, as queer relationships and identities gain greater social acceptance and legal recognition, and representations become more common in mainstream America—both on the screen and in the apartment next door—the discussion has broadened to include queer families of all stripes. For the parents we spoke to, gender identity was one of many interconnected, complicating factors of family life, including transracial parenting, co-parenting with an ex, parenting a child with physical disabilities, and breastfeeding under the spectre of cancer.

Family structures beyond the two-parent nuclear household—for queer and straight families alike—have become the norm. Divorced, single-parent, unmarried, adoptive, multi-parent, and multi-generational families compose the majority of today’s child-rearing experiences.

Yet even those of us who’ve lived rebellious, marginalized lives as individuals may find hidden, unwanted reserves of conservatism when it comes to parenting. Many parents admitted to internalizing the paranoia surrounding children and sexuality, for example. Maybe you go from being enthusiastically leather-clad on a float to worrying about whether or not to “expose” your child to the Pride march. Maybe, like A.K. Summers, you feel wary that a focus on childhood gender may be obfuscating conversations about childhood sexuality; at the same time, you realize you have become “one of those people, making movie choices [with her son], who are like, violence: okay, sexuality: no.”

Halberstam insists that parenting cannot be isolated from other forms of social change. We need, he says, to confront our reluctance to move beyond “traditional,” prescriptive parenting values that are neither reflective of current family structures nor what is truly best for children.

“I think you’ll see a bunch of books coming out in the next couple years saying, ‘This is genderqueer parenting, these are the ABCs of genderqueer parenting.’ You can already see it, right? The thing is, I don’t think the introduction of genderqueer parents into parenting systems should be the occasion to instruct those parents on how to parent. The challenge here is not just to fold gay, lesbian, and trans parents into current parenting norms. The challenge is to transform parenting.” In fact, Halberstam continues, parenting is already in another phase.

“It’s just that we just haven’t really named it or classified it or talked it through.”

*Name has been changed to protect privacy.