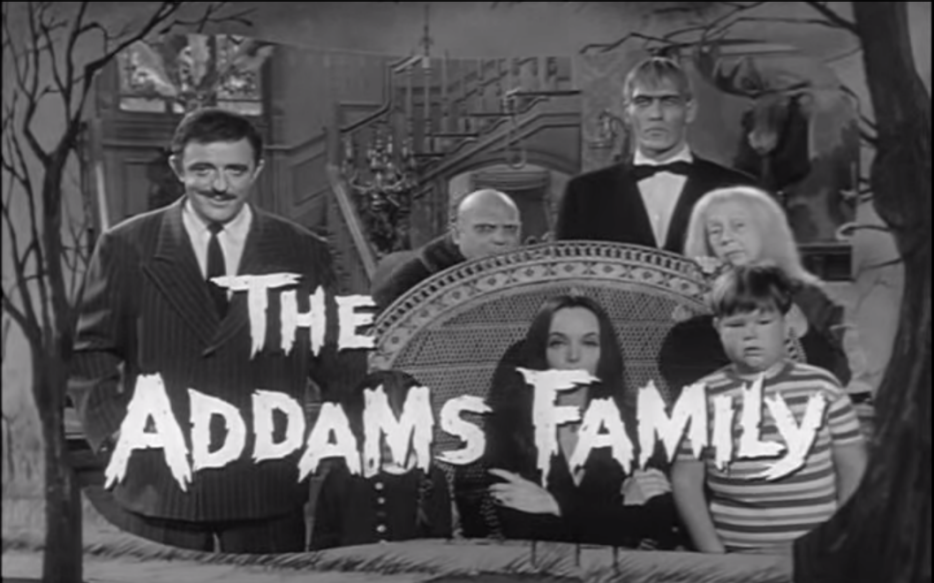

Were a suburban American family to find themselves at home on the evening of September 18, 1964, chances are decent that that they would be watching network television. Pickings were slimmer back then; perhaps they idly caught themselves flipping between The Great Adventure on CBS and Bob Hope Presents on NBC. Switching to ABC, however, they’d have caught the premiere of something unusual. On screen, a dark and gothic mansion stood out in its small town. Inside lived a family that inadvertently terrorized their neighbourhood. There was a vampy housewife named Morticia Addams. The family’s butler, Lurch, resembled Frankenstein’s monster. Their house pet, Kitty, was a barely-domesticated lion. They lived by their own rules, oblivious to how the rest of the world saw them. They were completely one of a kind.

Until, of course, the same American television audience watched CBS a week later on Thursday, September 24. Then, they would see a completely different gothic house that stood out from their completely different small town. Inside lived a family that inadvertently terrorized their neighbourhood. There was a vampy housewife named Lily Munster. The family’s patriarch, Herman, resembled Frankenstein’s monster. Their house pet, Spot, was a barely-domesticated dragon. They believed themselves to be living by society’s rules, completely oblivious to how the rest of the world saw them.

The Munsters and The Addams Family, two sitcoms, developed independently, about ghoulish suburban families, premiered within a week of each other. Both shows would last for exactly two seasons before being cancelled in the spring of 1966. And while neither show lasted long in its original incarnation, both would inspire massive cult followings, spawning tie-in merchandise, reboots and reunion specials, TV movies, feature films, Saturday morning cartoons, a Broadway musical. The two shows were built on the premise that these families were at odds with American society, and yet both struck chords with prime time audiences that, in between laughing at sight gags, recognized something in these ostracized characters who abided by a consistent set of values that made sense to them.

Generally, the question that I’m met with when I bring up my obsession with the Addams and the Munsters is, “Okay, so which show ripped off the other?” The short answer is: neither, at least not any more than every American sitcom is a rip-off in some way. Both shows were formulaic, half-hour, domestic comedies that included familiar plotlines of the era (including “out there” storylines like getting struck with amnesia, or brushes with pop stardom). At their core, though, they were wildly different. One family was the creation of a major movie studio repurposing some of their most famous characters, while the other was created by a lone artist sketching in his New York City apartment. The Munsters, though they had strange customs, ultimately behaved and lived like a traditional nuclear family, whereas the Addamses had no interest in fitting into an archetypal family structure. They were both outsider families, yet for completely different reasons. Besides, neither show could truly rip off the other in subject or spirit; they were both pop culture moments decades in the making.

*

American audiences’ obsessions with on-screen monsters started years before these families entered primetime. Universal Studios began releasing their iconic horror movies in the 1920s, with silent films such as 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and 1925’s The Phantom of the Opera (both starring Lon Chaney) terrorizing audiences. By the time talkies were being popularized in the early thirties, Universal was expanding their repertoire. In 1931, they would introduce the world to two of their most infamous creatures: Bela Lugosi starred in Tod Browning’s Dracula, and later that year Boris Karloff would play the monster in James Whale’s Frankenstein.

Universal didn’t invent Dracula and Frankenstein, of course. The source materials came from novels penned by Bram Stoker in 1897 and Mary Shelley in 1818, respectively. Nor were these films the first adaptations of either story. Both had been interpreted in multiple stage plays and silent films, most notably in 1922’s vampire movie Nosferatu. But the roles played by Lugosi and Karloff popularized the contemporary images we have of Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster today.

The monster in Mary Shelley’s book (the full of which was Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus) was eloquent and sensitive, having taught himself how to speak and read after being abandoned by his creator, Dr. Victor Frankenstein. According to the biography Boris Karloff: More Than a Monster by Stephen Jacobs, it was screenwriter Robert Florey who wanted to turn him into a “grunting, thuggish monster,” a more obvious outsider to polite American society than the literate creature in Shelley’s novel. Universal’s head makeup artist Jack P. Pierce, who had also worked on Dracula, spent four months creating the monster’s look, frequently working with Karloff late into the evening. The monster’s flat, square head came from Pierce deciding that Frankenstein (the scientist) had no official surgical background and would just squish the skull back on after inserting the brain. The bolts on the monster’s neck were inspired by the fact that he ran on electricity.

When the film was released in November of 1931, it broke records all over America. In Minneapolis, people fought to get into the screening. Women were reported coming out of theatres trembling. Critics warned audiences to keep children away from the movie; Frankenstein’s monster in all his grim glory was far too frightening to be seen by young eyes.

Meanwhile, across the country from Hollywood’s Universal Studios, a young cartoonist was beginning to launch his career. Charles Samuel Addams was born in Westfield, New Jersey, in 1912. He came from pedigree; his maternal grandmother was Emma Louise Tufts Spear (from the same family after whom Tufts University is named) and he was a distant relative of social reformer Jane Addams. He was popular in high school, where he contributed drawings to the student publication. In 1931, the same year Frankenstein and Dracula was released, he moved to New York City to attend art school. He began submitting artwork to a burgeoning literary magazine called The New Yorker.

The New Yorker published one of Addams’s small illustrations as a decorative spot in their February 6, 1932 issue, for which he was paid $7.50. He continued to submit his cartoons to them while working as a layout artist at the pulpy True Detective magazine (his jobs included diagramming crime scenes and touching up images of corpses). Throughout the 1930s, The New Yorker bought more and more of his cartoons. His work became increasingly popular as it became creepier; a combination of indulging his own macabre impulses and the magazine assigning him ideas they felt suited to his style. (Earlier New Yorker comics were frequently the result of collaboration, with writers submitting premises or jokes that would be drawn by staff artists.)

Addams’s strongest comics were ones that took the reader a minute to register why they were so unsettling. An early hit of his depicted a downhill skier whose tracks in the snow behind him pass on either side of a tree. My personal favourite includes a woman sitting in an armchair in conventional living room, speaking on the phone. The caption reads, “Nothing much, Agnes. What’s new with you?” The woman is holding a small pistol in her lap. On the bottom left hand corner, pushed mostly out of frame, are the lifeless legs of her victim (her husband?). “Addams’s comedy was never simply cruel, and always had strong Dadaist qualities,” writes Iain Topliss in The Comic Worlds of Peter Arno, William Steig, Charles Addams, and Saul Steinberg. “What permits the success of the joke against the crazy improbability of the idea is the extraordinary solidity and realism of Addams’s drawing.”

His work could also be wildly racist; favoured subjects of his include African witch doctors and cannibals, comics whose punchlines generally revolved around the same joke (“Who are we having for dinner?”). Later in his career, The New Yorker would stop printing these cartoons. For all his subversive humour and fascination with the weird, Addams was still very much part of the establishment. He was endorsed by the biggest names in New York publishing, drove a Bugatti, and in later years dated Greta Garbo and Jackie Kennedy. Part of the reason he could lampoon polite American society so well was because he was right in the middle of it.

In August 1938, Addams sold a cartoon that featured a lithe, witchy woman in a draping black dress standing with a tall, bearded companion in a dusty, decrepit, cobwebbed mansion. A salesman is at their door, promising a vacuum that is “Vibrationless, noiseless, and a great time and back saver. No well-appointed home should be without it!” According to Chas Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life by Linda H. Davis, the woman in the cartoon wasn’t modelled on anyone in particular, though she did carry elements of Gloria Swanson. Ultimately, she was Addams’s vision of his ideal woman.

The witchy woman made her way into more of Addams’s cartoons, much to the delight of The New Yorker’s readers. He gave her a tall, brooding butler that, according to Frankenstein: A Cultural History by Susan Tyler Hitchcock, was not inspired by the Universal monster (Addams had been drawing similar figures since childhood). Still, Addams found himself a fan in Boris Karloff, who wrote the introduction to Addams’s 1942 collection, Drawn and Quartered. That same year, Addams gave his witchy woman a new husband, replacing her earlier, bearded companion with a stout, short figure, hair parted in the middle like a toupee. “Addams, a Democrat, had based the young witch’s lover on a reasonably attractive man, Republican Thomas E. Dewey,” writes Davis, “but Dewey crossed with a pig.” The children were introduced in 1944. There was a girl, who was a smaller, glassy eyed version of her mother, and her blonde troublemaker of a brother, whose persona was inspired by comedian W.C. Fields. A bald, bulging-eyed man with an ambiguous relationship to the family debuted in 1946. It was clear he shared the rest of the family’s sensibilities: he is first seen in a movie theatre audience and, while the rest of the patrons stare up at the screen weeping, his face is one of sheer delight. Addams’s own celebrity soared. Fans couldn’t get enough of this mysterious Addams Family.

*

By the 1950s, Universal Studios’ stable of monsters had developed into a full-blown empire. There were more iconic characters introduced, including a portrayal of the Wolf Man by Lon Chaney Jr., Lon Chaney's son, in a 1941 movie of the same name. There were horror sequels (most famously 1935’s The Bride of Frankenstein) and multiple crossovers (such as 1943’s Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, with Lugosi playing the role made famous by Karloff). There were also comedies; in 1948, Universal released Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, with Glenn Strange playing Frankenstein’s monster, Bela Lugosi and Lon Chaney Jr. reprising their roles as Count Dracula and the Wolf Man, and Vincent Price voicing the Invisible Man. These actors played their roles straight, but the movie was pure slapstick. (Reports differ on whether Karloff abstained from the movie because he wasn’t interested in turning his character into a farce, or whether he was even offered a role in the movie in the first place, but he would go on to star in 1949’s Abbott and Costello Meet the Killer, Boris Karloff, and in 1953’s Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.) The monsters who were once considered too terrifying to be viewed by children were now starring alongside America’s most beloved comedy duo.

The biggest boon to the monster movie industry came with the popularization of television. In 1951, about a quarter of American households owned a television. By 1957, that number had risen to 78 percent. That year, Universal Studios released fifty-two titles from their horror back catalog, including Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Wolf Man, to local broadcasting stations. The programming marketed through Screen Gems as “Shock!,” though depending on what city you lived in, you might know it as Creature Feature or Chiller Theater. A new generation of children that wasn’t yet born when these movies were first in theatres would sneak downstairs late on Friday or Saturday nights hoping to catch the exciting thrill of a monster movie that was unlike any of the programming available to them the rest of the week.

Television stations leaned into the spectacle of it all, and had the films introduced by hosts dressed up in costumes, who became celebrities in their own right. Cleveland’s WJW TV had Pete Meyers playing the part of Mad Daddy. Los Angeles had bondage model and exotic dancer Maila Nurmi transform into Vampira. As campy as she was glamorous, many noticed similarities between Vampira’s look and the witchy woman of Charles Addams’s cartoons; she credits her whole persona as being inspired by his dark sensibilities. According to Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror by W. Scott Pool, Nurmi “borrowed heavily from Addams’s mordant and shocking humor. She owed a great deal of her inspiration to his mockery of bourgeois notions of family and respectability.”

In 1957, Addams’s career was going strong, and he had six cartoon anthologies to his name. His next book would take things in a different direction. Dear Dead Days, which was billed as “a family album,” did have a few of Addams’s illustrations of his notorious family heading the chapters. But the bulk of the book consisted of pictures that Addams had collected over the years of curiosities and natural phenomena: circus sideshow performers, medical anomalies, coffin advertisements, old surgical tools, anything and everything odd. The collection showed that Addams’s tastes in the unusual veered less towards the supernatural movie monsters of Universal Studios and more to phenomena that could be observed in real life. He was drawn to outsiders and weirdos, the marginalized and bizarre. One image, captioned “The Effigies of Barbara, the wife of John Michael, taken in the 27th year of her age, the daughter of Balthazar & Anne Ursler, Born in Ausburg in Upper Germany in the year 1929” featured a young woman whose face was completely covered in hair. Perhaps one could see in this image the influence this young woman would have on one of Addams’s own comics creations, originally known simply as “It.”

*

Reports differ on which show existed in development first. Rick Hull’s documentary The Munsters, America’s First Family of Fright, claims Universal quickly pushed forward a TV show to capitalize on their iconic characters after learning that ABC was creating two spooky primetime series of their own, Bewitched and The Addams Family. But years before, in 1945, Bugs Bunny animator Bob Clampett had pitched a family-friendly cartoon series named The Monster Family, and in 1947 playwright Wolcott Gibbs tried creating his own adaptation of the Addams Family. Addams met with producer David Levy during the development of the show and provided notes for each character, but ultimately had little creative involvement.

Merchandising tie-ins for the Addams Family had started in 1963, a year before any show was made. When Aboriginals, Ltd. began marketing cloth dolls, it was clear that these characters needed names. The doll company picked the name for the girl, calling her Wednesday after the line from the nursery rhyme, “Wednesday’s child is full of woe.” Addams named the mother and son Morticia and Pugsley. (He originally pitched “Pubert,” but the doll company said no. Later, that name would be used for for a third Addams child in 1993’s Addams Family Values.) The actor cast to play the father in the show, John Astin, picked the name “Gomez” from a list of options Addams gave him. The rest of the family became Uncle Fester, Grandma Frump, Lurch the Butler, Cousin Itt, and Thing, a disembodied hand that had been seen changing records on a record player in one of Addams’s cartoons.

Nat Perrin, who had worked with the Marx Brothers, was hired as head writer. The creepy creations would be played by beautiful celebrities palatable enough for primetime. Astin, a longtime fan of Addams’s work, was considerably more attractive than the Gomez of cartoons. Carolyn Jones would play Morticia, former child star Jackie Coogan (who had worked alongside Charlie Chaplin in The Kid) would be Fester, and Vaudeville star Blossom Rock was cast as Grandma Frump.

Though a range of child stars were auditioned, the children were played by nine-year-old Ken Weatherwax and six-year-old Lisa Loring, both of whom had bit roles in TV shows behind them. Today, many people associate Wednesday with Christina Ricci, who was several years older than Wednesday was when she was cast as the character in the feature films in the 1990s. But there is something inspired about the casting of someone as young as Loring to play Wednesday; her creepiness is accentuated by her age. Loring has none of Ricci’s tweenage sullenness as she plays with her headless Marie Antoinette doll; she is merely a child growing up with a completely different code of behaviour.

This was the major appeal of the Addams Family: though there were some supernatural elements in the show (the existence of Thing, doors that open and closed on their own as if by magic), the family themselves were, ultimately, human. There was no explanation for their otherness—they merely found conventional society to be uninspired, and preferred to do things their own way. The opening credits of the show, featuring Vic Mizzy’s iconic theme song that introduced the family as creepy, kooky, mysterious, and spooky, had the family standing together as if posing for a portrait. While Morticia and Gomez engage seductively with the camera, Gomez wearing an unsettling smirk, the rest stare off into the distance, glassy eyed and slack jawed, just looking slightly off.

The Munsters were social outcasts as well, but the reasoning behind their otherness was obvious: they were monsters. Harvard-educated Fred Gwynne, who previously starred in the sitcom Car 54, Where Are You? was cast as Herman Munster, a Frankenstein’s monster resembling Karloff’s depiction. Gwynne’s Car 54 co-star Al Lewis was cast as his father-in-law, Grandpa Munster, a vampire who went by the name of Dracula back in the “ol’ country,” Transylvania. A twelve-minute pilot was shot in colour with Joan Marshall playing Herman’s vampire wife, Phoebe, and Happy Derman playing their werewolf son, Eddie. The tone of the pilot felt too dark to the producers Joe Connelly and Bob Mosher, who had previously worked on The Amos ‘n’ Andy Show and were the creators Leave it to Beaver. Joan Marshall’s performance was sultry, not unlike Carolyn Jones’s depiction of Morticia Addams; the original Eddie was downright rabid. Connelly and Mosher wanted their monster family to be wholesome and relatable, a version of the Cleavers that happened to be undead. Herman’s wife, now called Lily, was recast with the glamorous but warm Yvonne DeCarlo, and Butch Patrick’s version of Eddie was much more buoyant. Though most sitcoms were being filmed in colour, filming for the Munsters switched to black and white (like the Addams) to save money on production costs. They would be using the same makeup artists and other resources that the Universal feature films had.

The final member of the Munster family was cousin Marilyn, a pretty, sunny, human blonde that, according to The Munsters: Television’s First Family of Fright by Stephen Cox, was named after blonde bombshell Monroe. Marilyn was never given much to do beyond existing as a punchline about her supposed ugly, abnormal appearance. She was played by Beverley Owen, who was eventually replaced by Pat Priest when Owen left her contract to move back to New York. There was never an explanation given as to how a human ended up in a family of monsters, though there was also no explanation as to how a Frankenstein’s monster and a vampire could give birth to a werewolf.

*

The August 21, 1964, cover of Life magazine featured the headline “AT VIETNAM BORDER GENERAL KHANH EYES THE ENEMY” against an image of the South Vietnamese premier. Inside the magazine, somewhere between a photo essay about the U.S.’s first direct action against North Vietnam and the second part in a series profiling President Lyndon B. Johnson, was a spread entitled “TV’s Year of the Monster.” Charles Addams’s cartoon family was pictured beside their television counterpart, followed by a full page image of Fred Gwynne’s smiling Herman Munster.

“Cowboys, surgeons, and hillbillies have had their day,” went the piece. “Now it’s the Year of the Ghoul, and the new fall season, which will burst upon us next month like a spray of lightning over Frankenstein’s castle, will be strictly from beyond the grave.”

The Munsters and the Addams couldn’t escape each other. In July 1964, a month before that Life Magazine feature came out, the shows were written up in a New York Times piece by Paul Gardner entitled “TV is Preparing a Monster Rally.” It included quotes from executive producers of both shows, explaining why their family was special. “They are contemporary people—good people,” said Joseph Connelly about The Munsters. “Their problem is the way they look.” About the Addamses, David Levy said, “Ours really isn’t a horror show. Our people have red blood. They’re—well, bizarre.”

The week that both shows premiered (the Munsters did significantly better in the ratings department, though both had respectable viewerships), the two found themselves back in the Times, in a review by Jack Gould entitled “TV: Horribly Engaging.” In it, Gould comes down firmly on the side of the Munsters:

“The creators of The Munsters have the right approach, the approach that was so completely missing from The Addams Family. Herman Munster, the head of the house; Lily, the vampire-looking spouse beset by household chores, and Grandpa Munster, an erstwhile Dracula who does not realize he has passed his prime, take their physical appearances for granted and see nothing unusual in the grotesque and macabre decor that distinguishes their home.”

It’s interesting that the elements that appealed to Gould are the parts of the Munsters that reveled in normalcy. After all, the Addams’ saw nothing unusual in their way of being either. Susan Sontag’s first major essay, “Notes on Camp,” was published the same year both shows premiered. In it, she writes, “Camp taste turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgement. Camp doesn’t reverse things. It doesn’t argue that the good is bad, or the bad is good. What it does is offer for art (and life) a different—a supplementary—set of standards.

In the first episode of the Addams Family, a truant officer visits the family to enroll the children in school. This was a common formula for the show, especially in its first season: someone from the “regular world,” like a politician or neighbour, would pay a visit to the Addams’ home only to be shocked by their way of doing things. (The show repeated a lot of gags, and no matter how many times Morticia cut the head off flowers or Lurch said “You rang?” in his baritone, the laugh track roared along.) Wednesday and Pugsley are sent to school, only to come home horrified by the stories they are forced to read in which a knight in shining armor kills a “poor, defenseless, dragon.”

“Grimm’s Fairy Tales,” says Morticia, reading off the title of the offending book. “What a lovely name, Grimm. How could he write such terrible stories?” It’s one of the inconsistencies of the show; Morticia and Gomez regularly quote Shakespeare, but are unaware of the original stories by the Brothers Grimm, whose gruesomeness would be right up their alley. These incongruities between their standards pop up depending on who is writing an episode or what the nature of the joke is. They’ll frequently use “gloomy” and “bleak” as compliments, but also use “cheery” as a positive when describing something like poison ivy as a decoration. Their campiness came not in a reversal of good and bad, but in throwing out notions of good and bad taste altogether for the sake of what amused them. In these moments, I’m reminded of playing “opposite day” as a kid. Occasionally when playing, we’d express opposites to entire sentiments—so the opposite of “I hate laughter” would be “I love laughter,” but occasionally become pedantic for the joke, finding the opposite for every single word, so that “I hate laughter” becomes “You love crying.”

There are important elements that remained consistent throughout the series. Gomez and Morticia were madly in love, Gomez especially taking every opportunity that came his way to express it. They rarely had petty squabbles or misunderstandings like couples in other domestic comedies; most of the show’s conflicts came up during interactions with a visitor. They were wealthy, but didn’t work. References were frequently made to Gomez’s stagnant law practice or investments, but he was notoriously terrible at both, a fact which amused him the same way crashing his model trains did. Morticia and Gomez spent their days with leisure activities, gardening, knitting, fencing, zen yogi [sic], and they had a full-time butler, Lurch, to take care of housekeeping. They were good-natured and exceedingly polite, completely oblivious to how they ruined the lives of most people who came their way; a frequent plot would be the Addams going out of their way to “help” an event like a political campaign or charity auction, only to have their meddling make things infinitely worse for whoever they were trying to help; they would come out unscathed.

The two strongest episodes from the show’s first season come when the Addams meet people who are cultural outsiders in their own right. In “The Addams Family Meets the VIPs,” a pair of foreign dignitaries are brought to the Addams home when they want to see a “normal American family.” They observe the Addams’s bizarre behaviours as typical American customs, and conclude that they belong to a more advanced society.

In “The Addams Family Meet a Beatnik,” a young rebel without a cause crashes his motorcycle into their front yard. They bring him inside after he falls unconscious, and as he comes to he looks around and says, “A couple of Aspirin and its gonesville for you spooks.” Gomez is delighted by his countercultural slang. “You certainly turn a colorful phrase,” he says. “Mrs. Addams and I are fascinated by the study of language and philology.” Rocky the beatnik stays with the Addams while he waits for his motorcycle to be fixed, and though he’s terrified of their pet lion and carnivorous house plant, the family starts copping his manner of speaking and admiring his skull-printed leather jacket. When Rocky’s tycoon father shows up at the end of the episode, Rockwell Sr. takes one look at the Addams Family and calls them kooks. “Well, they’re my kind of kooks and they dig me the way I am,” says Rocky.

Many of the early Munsters episodes follow a similar conceit: the well-meaning Munsters venture out into the world, only to be faced with terror by the townspeople. Usually this involves their hair standing on end or a hat flying off with a goofy sound effect as they run away in sped up motion. The Munsters had more room to play in their plots, however. Grandpa had a laboratory that he used for elaborate experiments that doubled as magic potions. He would mix up love potions to help with Marilyn's hopeless situation, or invent an “enlarging machine” to help Eddie grow. Mishaps would happen when his creations went awry.

Yet though the Munsters required a higher level of suspended disbelief, they were far more conventional in other ways. Herman had a job at the funeral home (doing what, it’s never specified), where his odd appearance goes unnoticed. Lily was a housewife who busied herself with cooking and cleaning. Money troubles served as a plot device in multiple episodes, with Herman or Lily taking up extra employment in order to pay the bills. (Gomez and Morticia occasionally worked, but almost always on passion projects that they then attempt to monetize. When Morticia takes up writing as a hobby, Gomez calls a publisher. When she is interested in sculpting, he invites an art critic over.) Herman frequently asserts himself as the man of the house, but like with many sitcoms of the era it’s done in a tongue and cheek way; every time he stands up to Lily he almost immediately backs down upon seeing her reaction, implying that she has more control in the relationship than is initially let on. They consumed middlebrow pop culture; as Gomez was quoting Shakespeare, Herman would reference Donna Reed.

Essentially, the Munsters were a typical American family, though they looked different, ate unusual foods, had a few unusual customs, and were born in a different country. In the show’s second episode, “My Fair Munster,” neighbour Yolanda Cribbins tells the mailman, “This was such a nice neighbourhood, until they moved in.” It’s not exactly subtle stuff, but midcentury sitcoms never really were. The Munsters lived in ignorant bliss about the ways others saw them. They strived for normalcy, but normal just happened to look a little different to them.

It quickly became apparent that Herman Munster was the star of the show. Six-foot-five Fred Gwynne played the role with a goofy sweetness, his rubbery face contorting itself until every reaction shot became a moment of physical comedy. He played well off Al Lewis’s coy and cunning Grandpa, and the show’s writers soon started writing plots that took advantage of the show’s larger-than-life premise to go for the truly absurd. Plotlines from the second season included Herman getting picked up by a Russian submarine while scuba diving and being mistaken for the missing link, and Grandpa using magic to turn himself into a horse after Eddie entered his father in a local bronco-riding contest.

The Herman-heavy episodes and busy production schedule (they produced seventy episodes in two years) proved brutal for Gwynne. While the entire principal cast (except Marilyn) required elaborate cosmetics, Gwynne had to spend two hours in the makeup chair every morning, and wore heavy padding under his costume that resulted in severe back and neck problems for years to come. He would also don full costume and makeup for public media appearances, of which there were many. People were fanatic over the Munsters; their fans included Marlon Brando, Liberace, and the Beatles. Their show had a broad, slapstick appeal that made them rock stars to children.

Still, the Addamses had their own champions. In The TV Book, writer Ellen Jaffe said about the Addams Family, “You had style, years ahead of your time. You had plants in your house back then that Californians are now growing in one room apartments. You had chairs that collectors kill for today. You were rich and pleasure-loving and romantic. You had a lot more class than your neighbors over at the other network, the Munsters, who always came off looking like poor relations. You did everything with a certain finesse, and hardly anyone in your family yelled.”

Part of the appeal of the Addamses came from the fact that, being so independently wealthy, they didn’t need to conform to the rest of society. Viewers watching could escape into the lives of rich eccentrics, with their exotic house pets and maze of a home. Yet the appeal slowly started to wear off later in the show’s run. In the second-season episode “Pugsley’s Allowance,” Gomez and Morticia are shocked and disgusted when they find out their son wants to find a job. “We Addams haven’t worked in three hundred years!” says Gomez. “You’d be the laughingstock of the whole family!” adds Morticia. Eventually, they give in and decide to encourage him. “Naturally, you’ll need a job keeping with your heritage and social status,” says Gomez, before suggesting that Pugsley become an astronaut. Somewhere along the way, the fun-loving weirdos of the Addams Family curdled into, well, bourgeois elitists.

There is no real story behind why the shows were cancelled; the ratings dropped during their second seasons, and the networks wanted to make room for newer fare. Few shows were being filmed in black and white anymore. Instead, kids were becoming obsessed with the candy-coloured Batman series, which premiered in January of 1966.

Still, the two ghoulish families had trouble staying dead. Most of the original Munsters cast reunited for two TV movies, 1981’s The Munster’s Revenge and 1996’s Munster, Go Home! (Marilyn was recast both times), and Al Lewis reprised his role for an animated special in 1973. The show underwent a complete recasting in 1988 with The Munsters Today, though this version was supposed to exist in-universe with the original series (they were all caught in Grandpa’s “sleeping machine” for twenty-two years). Two more straight-to-DVD releases came out in the 1990s, and several more reboots were attempted: the Wayans Brothers wrote a script in 2008 with Rose McGowan attached to star as Lily, Bryan Fuller’s 2012 attempt to create a darker and grittier television series Mockingbird Lane never made it past the pilot, and recently it was announced that writer Jill Kargman and comedian Seth Meyers were working on a new adaptation with NBC.

Even the biggest Addams Family fans might have trouble keeping track of all the adaptations and reboots. A short lived Hanna-Barbera cartoon (featuring a young Jodie Foster as Pugsley) aired in 1973, in which every episode had the family visit a different American city and hijinks ensued. A subpar TV movie called Halloween With The New Addams Family aired on NBC in 1977 with most of the original cast. There was Paramount Pictures’ well-received feature films, The Addams Family (1991) and Addams Family Values (1993), starring Anjelica Huston and Raul Julia, plus a second animated series in 1992 for which John Astin reprised his original role, a standalone TV movie Addams Family Reunion (1988), the 1998 YTV series The New Addams Family, and a musical by Andrew Lippa that made it to Broadway in 2010. In between writing drafts of this piece, it was announced that MGM will be producing a new animated feature, with Sausage Party’s Conrad Vernon directing. Though Charles Addams’s cartoons preceded the 1964 television program, every subsequent adaptation built on tropes introduced in the sitcom: Uncle Fester’s ability to conduct electricity, Gomez’s arousal at Morticia speaking French, Lurch’s monosyllabic way of speaking. Like The Munsters, The Addams Family has endured as a cultural shorthand for a type of all-American weirdness, with every subsequent generation wanting to reinvent them for their own.

The final episode of the original Munsters television program mirrored the premiere episode of The Addams Family, in which someone from the school visits the family out of concern for the children’s well-being. In “A Visit From the Teacher,” Eddie’s teacher visits the Munsters' home after she believes the boy made up his essay “My Parents: An Average American Family.” She is, of course, horrified. For all the overlap between the two shows, these episodes illustrate how they differ. In the episode that introduced television’s Addams Family to the world, Morticia and Gomez decide that the public school system is not up to their standards (in a later episode they would go so far as to purchase a private school). In the Munsters finale, Eddie has no problem completing his homework assignment, but the school takes issue with how he did it. Two families, one making the choice to extricate themselves from the banalities of American suburbia, the other trying to fit in but constantly finding themselves rejected. It’s a shame the two never got to meet.