June 1963

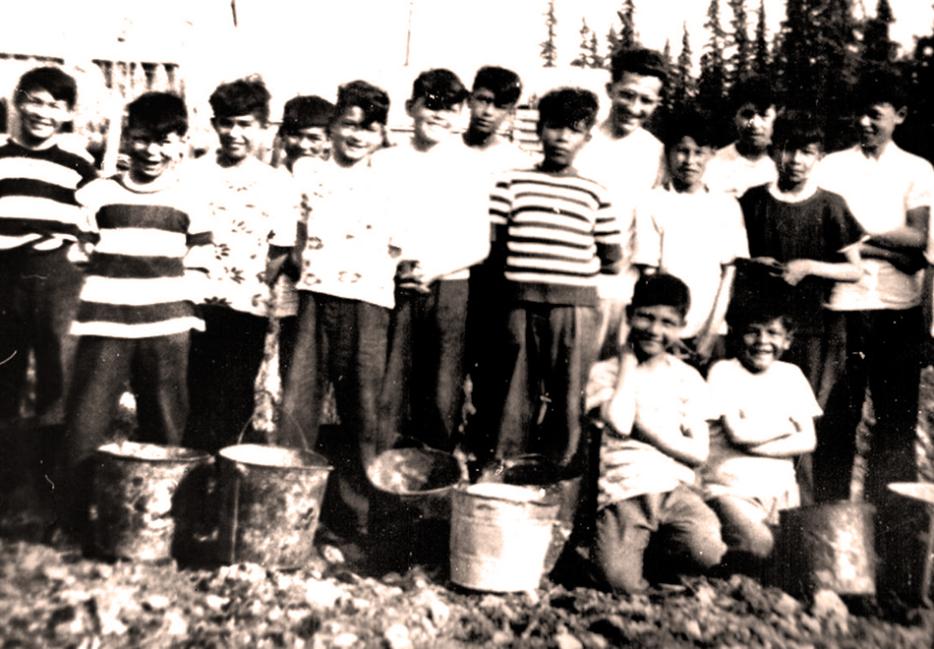

We made it. Twelve kids from my class of thirty graduated from Grade 8. Nine boys and three girls, including Amocheesh, Erick, Nicholas, Fred, Joe and Brandon. Some kids were held back, and others, like Tony, gone back to the bush to be with their parents, who had to hide them from the priests, Hudson’s Bay managers and the Indian Agents.

The day of our graduation, the school was a little noisier. At chapel, a few boys sang their own words to the songs. “Christ we never have to be here again, Praise be to God,” “Come Let Us Be Gone Forever,” stuff like that. After the service, Father Lavois stood next to Brother Jutras and they shook our hands on the way out. Some of the boys waited until they were out of the church, then wiped their hands on the grass or on their pants. No one said anything. We didn’t need to.

At breakfast, a couple of seniors started a food fight. Sister Wesley ran over and began shouting, but they just laughed as if nothing she could do would harm them anymore. It was like the spell had been broken and we were coming back to life. We all wore dark suits and mortarboards, which was lucky because some of the boys behind me started flicking ink in our last lesson. I looked at my hand on the black cloth. I’m still here, I thought. I didn’t die. For a long time, I had watched my body, as if everything was happening to someone else. I had listened to conversations as if I was in another room, and everything was happening from far away. As I stared at my fingers, I thought, This is me. I’m here again. I didn’t quite believe it.

My parents had arranged to meet me during the end-of-year concert. I thought about going home before the concert to say hello, but part of me didn’t really care that they were back in town: we had grown more distant during the eight years I was at St. Anne’s. I didn’t write as much anymore. Not that it mattered; my letters didn’t contain much except bland descriptions of anything positive I was allowed to explain—the school censors removed the rest—which meant that they were pretty thin.

So after the final bell rang, I hung about the playroom. Brandon was playing checkers. I was still angry at him, but suddenly I realized it didn’t matter. He’ll never be mean to me again, I thought. I’ll never be whipped or be made to eat my own vomit. I survived the electric chair and the daily bed-wetting exams. There would be no more annual “medical exams” by Brother Jutras. I was alive. Life had to get better now.

*

I was standing by myself next to my beauty the Albany. It was a sunny day. Ahead was sky-blue water, and above the rocky grey ledges, deep green spruces jutted like spears against the sky. I came here to get away. Our family had continued to grow rapidly since the birth of Mary-Louise, so now we had Chris who was six, Leo who was five, Jane who was four and Denise who was two.

“You all right?” Alex said. He must have approached while I was lost in thought. I shrugged. I felt bad that I hadn’t been much of a brother to him while I was at school, but it was hard with all the rules. We weren’t allowed to do things like stroke each other’s hair or hug. They’d get you a sharp word or slap. And we weren’t supposed to talk much either. Not too loudly, and only at playtimes. We had drifted.

“You’re leaving,” he said. “I’m jealous.”

“You’ll be out soon enough,” I said.

“I’m going to miss you.”

“Yeah, well . . .” I said. He looked hurt. “Me too.”

*

“Be good, Ed,” Mama said. Mama, Papa and Chris were seeing me off at the Fort Albany airport, which was a one-room wooden shack. Alex was at home minding the rest of my brothers and sisters. Four other St. Anne’s students were flying with me—Fred, Erick, Nicholas and Angela—and their parents crowded around them, our elbows touching. The rest of the graduates would meet us in Timmins, and we would take the train together to Cochrane. From there, the girls would go on to their new homes in North Bay. We would take a bus to meet our new foster families in Swastika, then drive to Kirkland Lake.

“Yeah, okay, Mama.”

“We love you, Ed,” Papa said.

“You too.” I picked up my suitcase and walked to the plane. I didn’t look back.

We were loading our luggage onto a school bus in Cochrane. It was the first time I had seen something so big and yellow, actually it was the first time I’d seen any vehicle except in newspapers and magazines. In real life they were so fast. They whipped past, or swerved at the last minute. And the roads. They were smooth and hard. No grass or weeds anywhere. Down the street were tall posts with funny metal hats. I racked my brain trying to remember what I knew about them. I turned to Erick, who was had just finished stacking his bag.

“Erick. What are they?”

“What?”

“Those poles.”

“Oh yeah. I saw them in a magazine once. They’re lamp posts.”

No one could stop looking out the window all the way to Swastika. It wasn’t just the lamp posts. It was the metal signs sticking out from poles. And the white lines on the roads. And the building where we stopped to fill up the tank. No one knew where the gas came from, but the driver said it was piped in underground. Then we were back on the road again, heading toward the train station. We lined up and were given squares of paper with numbers on them, which Erick said were tickets. Once we got on board, we found seats, and everything whipped past, the grass and the rivers and the trees, which had stopped being still, and were flying faster than a pike slipping through my fingers.

*

In Swastika, we were herded into church pews with some St. Anne’s students from higher years, and other teens I didn’t recognize, flown in from northern residential schools.

At the front, a thirty-something man asked for silence and began talking.

“Hello, boys! I’m Douglas Cooper.” It was our foster home supervisor. “I’m here to manage the transition from residential to high school. Fortunately, the Indian Affairs Branch of the Department of Citizenship and Immigration is very generous. It pays your foster parents to look after you and feed you. It provides funding for all your school supplies and clothes. It isn’t an excessive amount, so please try to be careful. We don’t have enough to pay for torn clothes or ripped jeans or other stupidity. And we give each of you a ten-dollar monthly allowance so you have something to spend on candy and movies and the like. Now in return for this generosity, we have set a few ground rules. The first is that there is no smoking or drinking. No going out after school, except for school activities. You are to come straight home as soon as school is out. Weekend curfew is eleven p.m. And please try to be as nice as you can to your foster parents. They try to do their best to be good caretakers.”

Mr. Cooper began matching us with foster parents. At my name, a tall man named Joseph Ryan stood up and waved. I scrutinized his face. He had greying hair, black bushy eyebrows and deep creases around his eyes. He seemed kind, like someone who might give you more food, if you asked nicely.

On the way to the Ryans’ house, Joseph turned around to the five of us—Fred, Erick, Amocheesh, Nicholas and myself—who were crammed into the station wagon. There would be ten of us staying with him, but we couldn’t all squeeze into the car, so we were taking two trips.

“It’s three to a room,” he said. “That okay?”

“What about one hundred and ten to a room?” Nicholas asked. They crammed us in tight at St. Anne’s dormitory, and the rest of us laughed.

“Huh?” Joseph asked.

“Forget it,” Nicholas said.

“What’s so funny?”

“Nothing, Mr. Ryan. Sorry.”

“Why were you all laughing?”

“No reason.”

“Tell me.”

“It was just ...” Nicholas looked scared. “We had to share with about a hundred other boys at St. Anne’s. That’s all.”

“Oh I see,” Mr. Ryan said. “Okay then.” He shook his head. “Good. Here you’ll be a lot more comfortable.”

The Ryans’ house was huge, bigger than any of the houses in Fort Albany—three storeys—with window shutters and a front porch. Mr. Ryan told us to quickly unpack, as dinner would be in an hour.

Everything was so different from St. Anne’s. No one deloused us, shaved our heads and confiscated our possessions. No one gave us new uniforms. Instead, Joseph’s wife, Irene, asked us our names, and said she would do her best to remember them, and then led us upstairs.

“I made up the beds for you,” she said. “Each boy has two drawers each.”

An hour later, we came down to a dinner table full of meat and other goodies. It was like the nuns’ table. There was roasted beef, gravy, mashed potatoes, peas, carrots, and afterwards chocolate mousse. Irene said we could eat as much as we liked, so I heaped more and more onto my plate.

“You’re hungry!” Joseph said.

“Yeah.” I was full already, but I didn’t know how much longer the food was going to last. “Is it okay?”

“Sure!”

“Thank you, Mr. Ryan.” I kept eating until my stomach hurt.

We weren’t allowed to watch TV or go out during the week, so after dinner we all went to our rooms. Erick opened his drawer and took out a needle that he’d brought with him from home. He wanted to play the pin game. Lots of boys played it at St. Anne’s, especially the older years. The rules were pretty easy. You scored a stroke on your arm until it bled. Then you passed the pin to the next person. He did the same. The winner was the person who could cut the most lines. We used to have to wait a few weeks until the scabs healed and then we could play again. I had done it once. It didn’t hurt that much. It felt more like a release.

Erick sliced his forearm, then gave the pin to me.

“Your turn,” he said.

“I don’t want to,” I said.

“Do it.”

“No. I don’t want to.”

“Wuss.” He looked about the room. “Who’s next?” No one said anything. “Chickens. The lot of you.” He cut a few more lines on his own arm and put down the pin. I turned away. He was in a dark mood, and I didn’t want to be part of it.

Excerpted from Up Ghost River (Knopf Canada) by Edmund Metatawabin, with Alexandra Shimo.