Mom always told us that our yellow dishes came from dog food. The plates were sturdy, easy to stack—perfect for grapes, cookies, pizza slices with the babysitter. We used proper plates for dinner, but still put our milk in the plastic tumblers, picking fights over who got the one with a handle. A few chipped or broke over the years. Three kids put dinnerware through a lot of spills. But that was the appeal of these dishes: even if they did break, they were free. Sort of.

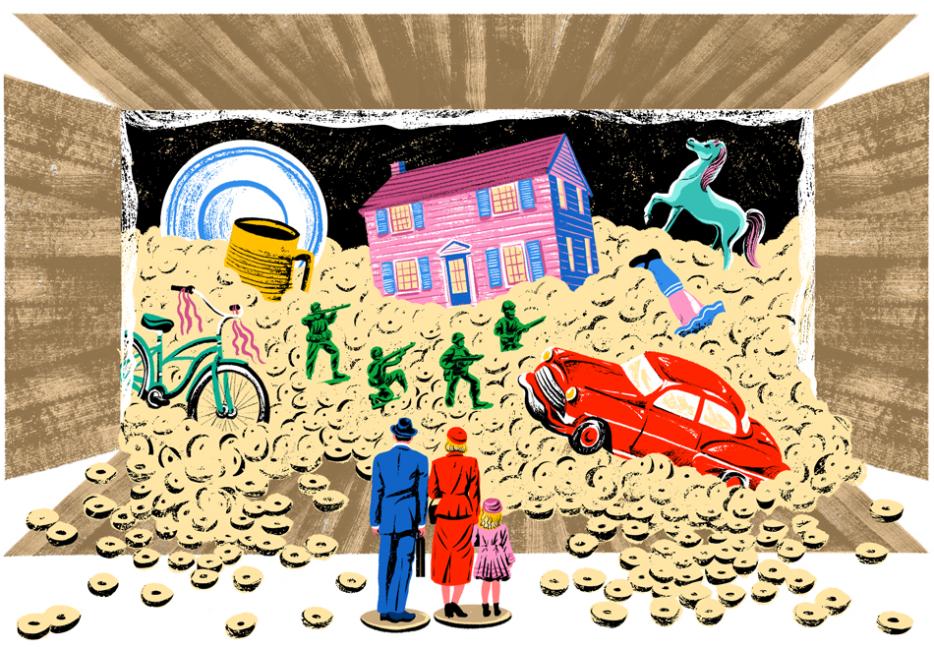

The school bus-colored dishware residing in my mother's cupboards to this day are free premiums: material items offered as incentives by retailers in exchange for making a purchase or completing another action. Sometimes these premiums are packed in with the item, like the cards of racist baseball legends, acrobatic toothpick-and-paper clowns, and plastic dogs and wolves found in Cracker Jack boxes of yesteryear that collectors will now pay hundreds for. But more often, consumers have to put in a little effort to get their reward: open an account, buy a certain amount of a product, sign up for a rewards program, or save up and send in packaging. These extras aren't actually free—you always have to buy something to get them — but they seem free, thus increasing the perceived value of the original purchase. Plus, the time you spend engaged in pursuit of the premium deepens your relationship to the company. Mom had to buy a lot of Purina dog food to get that dinnerware. The plates long outlasted the collies fed by the dog food, and when I got pets of my own, I started buying Purina cat food instinctively.

But, after their peak in the 1980s and 1990s, material premiums have become an increasingly rare advertising tactic. Marlboro doesn't give out miles to be redeemed for cowboy hats and cargo pants anymore. Marketing is as motivated by trends as any other industry, and this tactic got tired around the turn of the century. The quality of manufactured goods has declined, so they don't seem as worth it; besides, with more and more sales taking place online, physical rewards seem less appealing than, say, free shipping. Discounts, coupons, and rebates abound, as do virtual rewards.

Even Cracker Jacks have eschewed their iconic prizes. Instead of digging through caramel popcorn for a sticker, temporary tattoo, or other ephemeral piece of precious junk, kids will find a code for an augmented-reality mobile game. An app does seem like less of a treasure. But it's still an incentive, both for the bored customer at a baseball game, and for the advertiser who gets something perhaps more valuable than loyalty: their data.

*

Benjamin T. Babbitt and Phineas T. Barnum were good friends back in the 1850s, each the other's only peer in advertising. I like to imagine them as characters on a hangout sitcom, coming up with wacky half-hour schemes to lure the burgeoning class of American consumers into a renaissance of suckers. For as it was circus man Barnum who paved the path of relentless self-promotion that so many Kardashians follow today, it was Babbitt who figured out the power of a promise of something free (in this case, a lithograph) to get customers to buy soap from him and not someone else.

Premiums—usually called gifts, presents, or prizes in the 19th century—caught on quick. By the 1860s, gift book enterprises11Not to be confused with gift books, an industry of coffee-table-esque books that thrived from the 1820s through the 1850s. were common fixtures in urban centers, a sort of lottery whereby the purchaser of a book would get a random gift, according to Dr. Wendy Woloson's "Wishful Thinking: Retail Premiums in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America." These stores were finely furnished, but the books were mostly unsold remainders, otherwise unsellable, and the gifts were usually very cheap—twenty-five cents at the low end. The tantalizing prospect of a $100 watch almost never materialized, but it was there, bringing customers back to the thimbles and toiletries they actually won again and again. It wasn't the prize that was really the appeal. It was the anticipation, the excitement of what might be, what might transform them into something new, better, shiny too.

These early premiums schemes were largely composed of "marginal, slightly shady independent operators," said Dr. Woloson, who is an assistant professor of history at Rutgers. Gift book exchanges weren't exactly ethical, manipulating consumer emotions to get them to buy two things they wouldn't have wanted in the first place, but at least they didn't defraud war widows, as would other free premiums of the era.

Prize packages were sealed envelopes filled with "writing notions," basically scraps of paper unsuitable for printing elsewhere, and a cheap pin like you might find today in a gumball machine capsule. They were sold around the country, a sort of premium cum lottery cum multi-level-marketing scheme wherein agents (often soldiers, and later, their widows) were led to believe that they could make $15 a week22$240 in today’s economy selling prize packages (they did not). Even more exploitative were gift distributions, a complicated scheme in which con men leveraged people's #FOMO to sell tickets to lotteries that never actually existed. They were still effective: as many as 2,000 of these schemes circulated in the 1860s, taking advantage of a consumer market that was both avid and naive. "[R]etail premium schemes played on people's deep-seated emotions—hope, anticipation, desire, fear, and anxiety—and in doing so, encouraged and shaped a new consuming audience on a mass scale," Dr. Woloson wrote in "Wishful Thinking."

"Free is the most powerful word in the history of marketing," said Dr. Jason Chambers, Associate Professor of Advertising at the University of Illinois. The prospect of getting something for nothing made consumers "itchy with desire," to quote Dr. Woloson. Even after gift distributions collapsed as all cons do, premiums continued to evolve as a tactic. Adolph Busch was especially fond of giving loyal customers hat pins, watch fobs, and jack knives branded with his logo; one iconic Busch premium was a print of Custer's Last Stand, given away first to promote what was then the new "draught beer for connoisseurs," Michelob.

If you're like me and you're lucky enough to still have your grandma around, she probably remembers the next big moment in free premiums: S&H Green Stamps. Though the practice of giving tokens for loyalty goes back to Condor coins of the late 18th century, it wasn't until the late 19th century that these programs really began in earnest. They took their cues from the success of programs in which women received rewards for selling soap to their friends (in practice, closer to Avon than Younique). "Trading stamps were first issued in 1892 by the Milwaukee-based Schuster's department store, and were originally called the blue trading stamp system. Shoppers received a certain number of stamps with each product purchase, which they then pasted into booklets designed for the purpose," writes Dr. Woloson in a chapter on premiums in her upcoming book, The History of Crap. "Each booklet [represented] $50 in retail purchases, and could be redeemed for one dollar in merchandise [for a] two percent discount." The measly discount wasn't the appeal: it was the enjoyment of collecting, and the attendant anticipation it built.

These booklets recalled another popular pastime of the Victorian age: scrapbooking. It was a sentimental era, and people were already inclined to hold onto stuff; Sperry and Hutchinson just monetized that notion. The many consumers who were incentivized by the prospect of stamps but never actually redeemed them only increased the profit margin. And for those who did redeem their stamps, it was still a good way to get rid of merchandise that was not high quality. As the country entered the Depression, the word "free" was more powerful than ever—with a new focus on practicalities. In the booming economy of the jazz age, rewards were what Dr. Woloson called "petty luxuries, [such as] decorated china vases, or a gold-tipped writing pen, or something that you didn't need but something that you might want." But when budgets got tight, utility won out over shininess, and decoration took a backseat to durability. Depression glassware was everywhere in the 1930s retail landscape, packaged with cereal, handed out to moviegoers, and included with tanks of gas—increasing sales in the worst economy for a number of different industries. "[It was] an opportunity for different manufacturers to support one another in different ways," said Dr. Chambers. And though they aren't top quality (air bubbles were common) the patterns and colors of the translucent bowls, plates, and other dinnerware are still sought after today.

Another Depression-era premium had a more substantive and even spiritual impact on our cultural fabric. Under ancient Kosher dietary regulations, coffee, considered a legume, had been forbidden during Passover since its emergence in the 10th century. "Jewish grocery stores would put away coffee with the chametz under the incorrect assumption that coffee beans were kitniyot when in fact they are technically a fruit not a bean in that sense,” explained Elie Rosenfeld, CEO of Joseph Jacobs Advertising, in this Forward piece by Anne Cohen. But then, Joseph Jacobs entered the scene. In the 1920s, Jacobs convinced a Manhattan rabbi to spread the word that coffee beans were Kosher while talking Maxwell House into targeting this demographic. A decade later, Maxwell began printing a lovely blue and white haggadah (the text read at Passover seder services) to Jewish customers who bought a can of Maxwell House. Maxwell has printed 50 million copies of the Maxwell Haggadah, and it was even used by President Obama at White House seders.

With the advent of World War II, America's advertising and manufacturing efforts were consumed with the fighting overseas. "A lot of the cheap giveaways were imported from other places, like Japan and Germany, and we're of course not getting those products from those places," said Dr. Chambers. "[American] manufacturers were contributing to the war effort. They're not making TV trays." Instead, they were making tanks.

The attentions of the women, primary redeemers of premiums, were elsewhere too. "Women [were] thinking about stamps and coupons and things, but not to get free stuff, it's because that's what they needed to do to get their butter for the week," said Dr. Woloson. Whereas green stamps added value and an element of anticipation to the chore of grocery shopping, rationing elevated the collecting of coupons to a necessity.

But once the war was over, America's consumer spirit was back and hungrier than ever before. The baby boom brought focus to children as a major market; unhardened by the difficulties of the Depression and war, these kids were ready to hoard cheap toys. This wasn't a new tactic, exactly: the first premium targeted at children were Kellogg's Jungleland moving picture books, included as a part of its packaging in 1908, and bubblegum came with baseball cards starting in the 1940s. But it was Sam Gold, of Gold Premiums of New York and Gold Manufacturing Corporation, who really believed that catching the attention of children was the best way to sell to their parents. His companies made toys, cutouts, gum, and other kid-friendly products for cereals, pioneering the Saturday morning cartoon tie-in; the first premium Gold sold was a Rin-Tin-Tin telegraph key with Nabisco cereal. In a plot twist straight out of Mad Men, Gold died during a 1965 premium presentation to Cracker Jack.

While they were indoctrinating children through cereal box prizes, marketers were slowly realizing that another major market could be targeted through premiums. Advertisers had long misused images of black Americans as grotesque stereotypes to appeal to white consumers, and to be sure, this continued after WWII; one online collection of Sam Gold premiums includes Aunt Jemima paper dolls from the 1940s. But some advertisers were beginning to integrate, especially with the launch of major black magazines like Ebony and Jet as powerful vehicles to reach black consumers.

"The main advertising manufacturers that were specifically interested in the African-American consumer market [were interested] in ways that were different from the general consumer market," said Dr. Chambers. "In those cases, you still would have seen the same kind of things that you'd see in the general market—they just had a different focus. Coke and Pepsi in particular [in the '40s through the '60s] utilized aspects of African-American history as a free premium or pack-in or send-away." Tobacco and beverage companies in particular launched premium programs focused on African-American history lasting for decades; for one example, Dr. Chambers recalled busts of black innovators by famed sculptor Ruth Inge Hardison in a series called "Ingenious Americans" as a premium for Old Taylor whiskey.

Though the market was specializing to target different demographics, white women at home were still as much a target as ever. Housewares were a hot market in 1950s premiums. Boxes of detergent came with dish towels, knives, and flatware right in the carton. Decorated jars of jelly and peanut butter and decanters of maple syrup to be kept and reused after their contents were spent were often the premiums themselves, capitalizing on the Depression mentality of repurposing everything. While premiums were often right inside the packaging (or existed as the packaging itself), consumers were also willing to put in more effort and send away for their prizes. After all, housewives were expected to put their homes and children before themselves. They were used to giving away their own valuable time. Trading stamp programs, which required more effort, flourished among housewives until the gas crisis of the 1970s, when pinched gas stations stopped accepting stamps.

*

As trading stamps faded, premium programs grew. Cereal box premiums were so successful in targeting children that their advertisement on television was banned in 1974. Cigarette companies, reeling from similar restrictions in 1972, competed with each other to attract customers through rewards programs. Dr. Chambers remembered his father switching back and forth between different brands based on who had the gifts he wanted. This new wave of prizes were more likely to be branded, increasing the advertising value for corporations looking for a new foothold in the cultural consciousness. For some, the premiums were as habit-forming as nicotine.

"[In] the 1980s and 1990s, I [was] addicted to getting free things," wrote Mary Potter Kenyon in her 2013 book Coupon Crazy: The Science, the Savings, and the Stories Behind America's Extreme Obsession. Kenyon acquired a wide variety of products from these giveaways—a fancy umbrella from Gloria Vanderbilt perfume boxes, a coffee maker from coffee lids for her mom, Christmas lights from M&M bags. And especially toys and branded T-shirts for her six children. Until her teenage daughter told her that she didn't want a denim jacket with the Energizer Bunny on it, the Kenyon kids were walking billboards.

"Growing up poor, to give my kids this magic Christmas was an amazing thing for me, and it was all with company premiums," Kenyon said.

Kenyon put a lot of her time and effort into getting premiums by sending in packaging, receipts, and proofs of purchase. When she ran low on her own meticulously organized store of flattened boxes and saved wrappers, she turned to her family, friends, and neighbors—and their trash. She rooted through just about every garbage can she came across at the public pool or park for Hershey's wrappers to redeem for T-shirts. "We went to the swimming pool just as much for the swimming as for the candy wrappers in the trash bin," she said.

Kenyon's deal-hunting mindset was typical of the refunders in the 1970s through 1990s; there were magazines and conventions devoted to this community of consumers who sought out coupons, premiums, and rebates from companies. But while Kenyon stayed inside the law, others did not. Some refunders were way beyond simply using a neighbor's legally purchased discards: they were buying cash registers to create fake receipts, pooling their resources at conventions, and renting PO Boxes under false names to avoid the one-per-household requirement. In one case, the town of Rock Valley, Iowa was reprimanded by the USPS investigators in 1992 for a cash-for-trash scheme that involved half of the town's 2540 residents, netting a local fundamentalist religious school half a million dollars over two decades.

As savvy early advertisers exploited credulous 19th century consumers, coupon queens and rebate gamers exploited advertising executives who underestimated the savvy of dedicated deal-seekers. This contributed to a tightening of these programs in the late 1990s. Before long, premiums were becoming rarer and rarer; even boxes of cereal aren't packaged with toys anymore.

Fraud wasn't the only factor that doomed the free premium frenzy. Pepsi and Coke and Marlboro and Camel and other retailers were constantly one-upping each other, escalating their goods to attract new customers. Pepsi found themselves in a costly lawsuit when they advertised a Harrier jump jet for seven million points and someone called their bluff.33It was also mocked in an B-plot on a seventh season episode of 30 Rock (the one with Liz Lemon's wedding), in which Jenna was herself a free premium in a 1990s Surge commercial. Pepsi won, but the case itself was representative of the arms race premium programs found themselves in in the late 1990s.

Premiums could be a nuisance for corporations outside of the courtroom, too. "Manufacturers found the opportunity to transition to other things that had fewer logistical headaches," said Dr. Chambers, noting the possibility of breakage and all the other costs that come with transporting physical goods.

Advertisers are always trying to trick you a little bit—you know this, even though they try to make you forget. And when you wise up, they change their tactics. Consumers were more and more used to these inducements, which no longer held the power they did 100 years before. The quality of cheap goods were not improving. Carcinogens like soda pop and cigarettes—two of the most premium-friendly industries—fell out of fashion as minimalism came back into style. A new generation of advertisers were similarly bored with the advertising tactics that had fascinated their mothers. Both sides of the equation were getting more sophisticated, outgrowing the tactic. Everyone was ready to move on to the next thing.

The next thing was the Internet. The rise of the World Wide Web changed the landscape of retail and advertising as much as it did everything else. Premium programs were difficult to transact online; virtual rewards are way easier. Gasoline points aren't going to break in delivery. Discounts and free shipping are much more popular with online shoppers, as are rebates (which may explain why they survived while their cousin the premium grew frail). The premiums of yore didn't collect increasingly valuable customer data, and they're not as targeted as the ads you're probably blocking right now.

*

Premiums are not dead, exactly. The beauty industry still loves its gifts with purchase. Tote bags offered as inducements to donate to NPR or subscribe to The New Yorker are intellectual status symbols. When I bought some axe earrings from Etsy recently, I was pleased but not surprised to find a little axe pendant included as a freebie. Pepsi tries to restart PepsiStuff every so often, and Purina still advertises its rewards program on the back of the bags of food I buy for my cat, though I'm nowhere near organized enough to take advantage of it. A friend with young children recently received a number of tiny Marvel figurines for buying participating products at Kroger; she plans on making it into her own rewards program to encourage her young children to do summer reading.

Children are still motivated by toys, and Happy Meals will always come with a pack-in premium. "McDonalds is different," said Dr. Chambers. "There's nobody that's done anything as effective as Happy Meals." It is their point of entry for future customers, and it offers its own opportunities to create revenue through advertising tie-ins. Because of their reach and their ubiquity, they become that wonderful partner for the Olympics or Disney." Though there have been some occasional hits from other fast food chains—Hardee's had the California Raisins in the 1980s, and a friend on Facebook recalled asking for Land Before Time puppets from Burger King for Christmas one year—no one else can consistently compete. "It is their continued point of difference, especially in that young person's space," Dr. Chambers said. Happy Meal toys are not going away until McDonald's goes away.

Business gifts are also thriving, especially the arena of inducements to big events like baseball games. But there are signs of fatigue even there. While swag is still a major prong in marketing pharmaceuticals, even they have seen better days: OxyContin doesn't make pedometers anymore.

Sometimes getting a reward isn't just about the item—it's about the feeling of getting a little control back from a capitalist structure we cannot opt out of. Not long after the 2008 recession, there was a brief craze for couponing, chronicled in the 2010-2012 TLC show Extreme Couponing. "We were screwed by the system, and we want to screw them back," Dr. Woloson said of the post-recession surge in couponing. "It's a form of empowerment." The idea of empowerment is one way to build loyalty, even if it feels like revenge. The political can build a personal connection to a brand, too. Last summer, Penzeys Spices gave away Mexican vanilla with purchase as a fuck-you to President Trump, a political, memorable, and effective free premium that caused sales to spike and transformed the company's brand, earning goodwill from liberals everywhere. "The old methods of marketing are coming to an end," Bill Penzey bragged of his giveaways in Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, "and this is the new marketing." But it really isn't that new.

You won't see banks giving away toasters unless you're watching 1990s period piece Fresh Off The Boat, but banks do sometimes use premiums to induce new customers; I walked by a grill offered as an incentive by the Walmart bank while editing the second draft of this piece. My husband, a mailman, reported from his route one day to tell me about a display of dog accessories, wine corks, and backpacks advertised to new customers at Landmark Bank in Lawrence, Kansas. When I called Becky Tourtillott, Landmark's vice president of marketing, she confirmed that the days of "one-size-fits-all" rewards are long gone, and even among the rewards they do offer, premiums aren't the real draw. "Of our top ten most redeemed items, eight of them are gift cards," Tourtillott said. Even S&H Green Stamps have transitioned to virtual rewards in a bid for continued survival. When you can buy anything you want easily online, money is often more enticing than a hunk of plastic. But the thing about money is that it's cold and unfeeling; as on any big occasion, a gift is more fun to unwrap than a check.

"They're trying to make an appeal on an emotional rather than an economic register," said Dr. Woloson. In "Wishful Thinking," she quoted early twentieth century writer Henry S. Bunting, noting that premiums worked because they appealed “not to reason, but to the heart, to the emotions, to sentiment, to good will on the basis of implied acquaintanceship.”

But while they're fondly remembered, premiums are only sporadically relevant in the 2018 marketplace. Some of the tactics remain; Dr. Woloson pointed out that virtual rewards programs use the language of inclusion (e.g. clubs, membership) even though "you're just customer, you're just a data point." The retro appeal of free trinkets can't compete with corporate thirst for your personal information to better target you. "There's always the possibility of nostalgia marketing, if you want to utilize that," Dr. Chambers said, but he's skeptical that premiums will ever come back in a big way.

But the sentimental residue they always sought to leave remains. We still have a relationship with these companies. My aunt attributes her lifelong love of swans to a soap-related free premium her older sisters ordered for her as a baby. My grandma recalls the bike she got my uncle Tom from green stamps. My dad's obsession with baseball was launched in part by baseball cards on the back of Post cereal. My mom got animated and nostalgic talking about a particular premium: a director’s chair emblazoned with my name, which I adored as a child.

Mary Potter Kenyon once had a dedicated room with shelves and cabinets full of old receipts and flattened boxes and empty bags. When she moved in 1998, it prompted a realization: the era of free stuff was over, and she needed space for her six children more than she needed space for trash. "There was no point to saving all my garbage anymore," she said. She made a bonfire and burned all the scraps she'd spent so long collecting, incinerating her dreams of all the things she once hoped to get for free, or something like it.