Trumpets riff over a haze of cigarette smoke. It’s more of a cellar than a club, so steamy we can see the beads of sweat on the musician’s cheeks. The band plays under a neon sign reading “Hot Jazz Vesuvio,” and the chatter of the bargoers clocks in a solid din. Dickie leads Tom through the crowd, promptly smooching with a Neapolitan brunette. Tom looks on, surprised.

Cut to the next song, and Dickie sings onstage with his friend Fausto. His saxophone strapped to his neck, he’s too busy singing to play “Tu vuò fa l’americano.” Stage lights flash red. Dickie and Fausto, in duet, face each other, jerking their heads animatedly from side to side. On an instrumental break, Dickie whispers in Fausto’s ear while Tom applauds uproariously. “Un’altro amico americano questa sera,” Fausto calls, “Tom Ripley, vieni qua.”

Dickie smiles deviously as he yells to Tom, “Get on up here.”

Sheepish, Tom slips between Dickie and Fausto. When they reach the final chorus, the men sling their arms around each other. Dickie plants a kiss on Tom’s cheek when the song ends.

Cut to a voiceover, Dickie typing a letter home: “I bumped into an old friend, Tom Ripley. He says he’s going to haunt me until I agree to come back to New York with him.” He slides the rider across his typewriter, and Tom sits up, half-awake on the couch. Dickie hands him his glasses with a suave “Good afternoon.” We can only imagine what they’ve been up to all night.

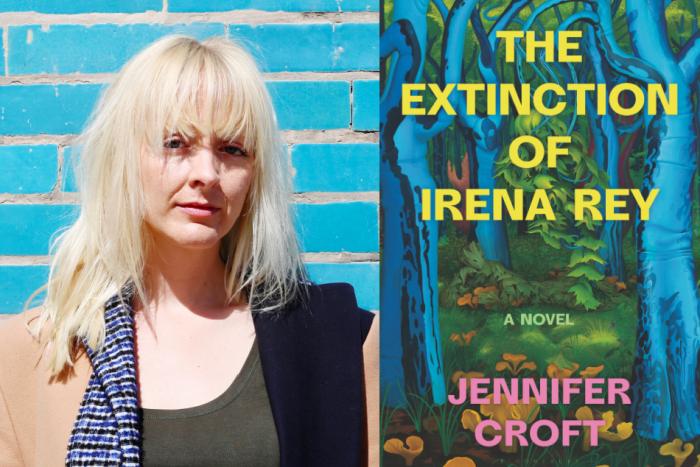

Anthony Minghella’s film adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley paints many lush scenes like these. Scenes where the stars—Matt Damon, Jude Law, Gwyneth Paltrow—wear billowing linen shirts while sailing off the coast of Naples. They enjoy late lunches on Dickie’s patio. They live in lustful luxury. They luxuriate.

After the spring gala, when the line for the photo booth stretched too long, my friends and I escaped the dance and sat down to watch the film, squeezing onto the couches of our common room where all year we had pregamed and debriefed our nights out.

Somehow, I’d never heard of The Talented Mr. Ripley. The title implies great physical or mental feats: a man who can forge signatures, impersonate voices, mix a stiff drink, and sing your fears away at the piano. Tom Ripley can do all of these things. There’s just more to the story.

Tom first meets Mr. and Mrs. Greenleaf while playing piano at a lavish function in Manhattan. They notice his Princeton jacket and ask if he knows their son, Dickie. The jacket’s borrowed but Tom goes along with their presumption nonetheless. Dickie Greenleaf lives in Mongibello, a hamlet outside Naples, hiding from his parents and their shipping business. They’ll pay Tom if he travels to Italy to bring Dickie home. Allowed entry into a new milieu, he assiduously studies Dickie before his departure, playing Chet Baker on vinyl and practising Mr. Greenleaf’s voice in the mirror. Upon his arrival in Mongibello, Tom quickly betrays Mr. Greenleaf, revealing the plot to bring Dickie home and unifying them against a common enemy.

I felt a kinship with Tom. Back in high school a friend had called me Matt Damon in the drawl of Team America, but the connection to Tom Ripley felt more psychic, fundamental. I liked to read. I liked to fade into the background. My glasses even looked like Tom’s. I even studied people to fit in. And then there was the matter of Tom’s feelings.

Tom wants Dickie’s light so badly. Marge does too. So does everyone. Every conversation Tom and Marge shared about Dickie’s influence and effervescence hummed on some deeper level for me. Their desire for his affection seemed to stretch past romance toward some platonic ideal, an all-consuming friendship with a maddening hold. I’d spent the entire semester on such a roller coaster of attention: the euphoria when he saw me; the sting of his indifference. I too shared these feelings for a man.

We didn’t get through the whole movie that night. It was too long, too late, and at some point we switched to The Big Chill. We’d turned off the movie before the plot twisted. I always fall asleep during late movies but that night I’d watched rapt. I was peeved that somebody had switched the movie without asking but didn’t feel I could say anything. From my secret spot in the circle, I knew I needed to watch the rest—that it might provide the manual I needed for my emotions.

Second semester, I decided to branch out. In my a cappella group, back from a semester abroad, was a Dickie—bright, ebullient, and endlessly attractive in a beanie, sweatshirt, khakis, orange-y boots. Two girls whispered at rehearsal, “He’s cute.” I watched as he reconnected with old friends, coaxing out their laughs with his. I looked away as I heard the girls whisper.

I’d only started drinking the first week of college and had never gotten drunk. Each night out, I counted my PBRs to calculate my control. Without articulating it to myself, I knew what might happen if I loosened my grip—it was why I hadn’t signed up for the hypnotist in high school. In the auditorium beside my friends at age fifteen, I’d watched as a closet case ogled the imaginary men in speedos the hypnotist had intended for the girls to enjoy. By nineteen, I’d burrowed deleteriously deep inside the closet. I hemmed in all my edges, my sense of humour and style repressed so I wouldn’t stick out.

Dickie’s hair had grown long during his semester in Dublin. He’d been mistaken for Harry Styles at a bar in rural Ireland. He had party tricks. His dad had trained him as a child oenophile. He talked tannins when we swigged Carlo Rossi at a cappella parties. He was everything I wanted to be. Dickie lived unabashedly. He was as attractive for his appearance as he was for his charms. I wanted to spin jokes like he did, wear clothing that indicated I’d thought about it for more than a nanosecond. So famished for recognition of who I was and who I wanted to be, I thought the full extent of my fascination with Dickie derived from how he’d already arrived at, what seemed to me, self-actualization. I didn’t plumb the depths of how I felt for him. New to a world he had access to, I called him a role model. I said I wanted to be his friend.

The hunger for this friendship was complete, consuming.

He said yes when I asked him to get dinner with me on campus. I looked forward to it for days. I asked other people in the group to meals too. I told myself the only reason I’d asked him to dinner was because I was asking everyone. In my journal, I wrote that I was making new friends. I’d cushion his name with all the others, but the others never came up in my journal unless I needed cushion. The other names never made me pay attention to each pen stroke as I wrote them—never made me smile when I saw them, really there, inscribed in my life.

And then the party. During a game of King’s Cup—a drinking game that on this February night had created a rule that exiled me to the porch—without hesitation, Dickie followed me outside. Bundled in his trademark fleece, as he asked me how I was enjoying our college experience and who I hung out with, I felt I had accessed him on some more authentic level, away from the spectacle of his friends. On campus, I’d worked so hard to claim space with him among the crowd. Now, out of everyone at the party, he’d come after me. He was quieter, intent, moony even (we all know who was really moony). Maybe, I thought, he’d wanted to see that side of me too. Whenever I felt ignored after that, I could conjure the warmth of that shared space. This was something to hold on to. He’d come after me.

After watching Mr. Ripley, I became obsessed the idea of magnetic people, that elusive category of person. They lived bigger, more fully. Insistent, expressive, self-assured, they had something I didn’t. Here was the root of my fascination. I needed to understand him to become better, so people might look at me like that, might love me like they loved him.

Dickie primed me for Mr. Ripley at the end of that semester.

You can imagine why I got scared when Tom Ripley smashed Dickie Greenleaf’s head in with an oar.

That summer, my family moved. Untethered from my hometown, no awkward encounters with high school classmates to avoid, I indulged in anonymity and nights alone. This brought me back to the movie in its entirety. I watched lazily, periodically checking Snapchat—my Dickie and I had a streak whose intricate weather I was attuned to. I hadn’t yet heard from him that day.

Tom and Marge stroll through Mongibello, and we hear a voice-over, Tom crooning Chet Baker’s “My Funny Valentine,” the song Dickie sang for her when they first met. They find him playing bocce with local men, and he winks, at Tom or Marge we can’t be sure. Tom’s singing pulls us back to the club. He sings directly to Dickie, who accompanies on the sax, stealing a glance at Tom over his mouthpiece. His notes soar when Tom sings for him to stay, little Valentine, stay. He watches Tom so intensely, we think that surely he’s feeling something too.

They come close to acknowledging what this something is. Against a backdrop of sexy jazz, they play chess, the board balanced over Dickie in the bathtub. Tom runs his fingers through the water and asks Dickie if he can get in, he’s cold. Stone-faced, Dickie contemplates before saying no. When Tom clarifies he didn’t mean he wanted to join with him in it, Dickie slides out and pads naked across the bathroom floor. While I know it’s not what the scene is suggesting—Dickie’s face is too stony, his intonation when he says, “I’m like a prune anyway” too peevish, bothered—I couldn’t help but read dejection in his naked stride, flirtation in him snapping his towel at Tom.

They had been inseparable. And now, Tom feels Dickie slipping away, magnetized instead to his old pal Freddie. Marge can commiserate. So many times, she has been pushed aside by Dickie’s friends (there’s Freddie and Fausto and Peter, and that’s just the boys).

“The thing with Dickie, it’s like the sun shines on you and it’s glorious, and then he forgets you and it’s very, very cold,” she says.

I went to sleep, checking for new Snapchats one more time, sighing my face into my pillow when the streak sputtered out.

Back on campus in the fall, I started going to counselling. Because he flaked on me more often. Because his real friends were back on campus and I felt him evaporating from my life. Because I didn’t know where to put these feelings and was afraid I would be stuck in them forever. Because maybe my whole vision of our friendship was naïve, ill-conceived.

In counselling, I made him plural. I talked about “these friends” who had me feeling so alone, who had me lusting for friendship when I already had plenty of friends I was neglecting for “them.”

It took weeks to shed the other names. Only when I knew my therapist wouldn’t push too much did I admit it was only ever about Dickie.

The Talented Mr. Ripley gave me the first words I would use to describe my feelings. I was weak to the charms of magnetic people. My desire to be seen, to attain this friendship had me glued to my phone. It sent me on dramatic runs where I’d exorcise the restlessness and pound pavement to the rhythms of my playlist, “Emo Run.” In Mr. Ripley, in my life, nothing romantic ever happens between the men. Everyone only wants validation. Everyone only wants to be friends. Yet I knew I didn’t only want to be friends.

In therapy we scanned my body, finding where the worry, where the hurt lived. My therapist asked about love and I spoke about the women I had been with on campus. I could feel the heat of where he was trying to go but neither of us went there. We talked about how it would feel for me to take control, to relinquish this desire. Maybe I could set myself free. I could find power in withholding my invitations and cope with the aftermath. If Dickie never rose to fill the gap I left behind, maybe I’d have my answer. I could move on.

Dickie stopped reaching out. Or rather, I didn’t hear from Dickie because I was no longer reaching out to him. I didn’t have any more texts to agonize over, or hours to wait for a response where I’d convince myself he hated me.

All of it was about Dickie. None of it was about Dickie. If it weren’t him, it would have been another man.

Tom doesn’t ever come out. Instead, he becomes.

It starts innocently. He tries on Dickie’s watch, tries on Dickie’s voice. Neglected one day while Dickie’s out with Freddie, Tom tries on his clothes, singing and dancing through his room. The narrative forks. He doesn’t want to be with Dickie. He wants to be Dickie. The “be or be with” question haunts many of us as we begin to question our sexuality, and for Tom Ripley, his desire is cannibalized by this vicious hunger to become his charismatic, affluent, attractive friend.

In an essay for CrimeReads, “Queer Friendship and the Psychological Thriller: Desire, Identity, and Violence in Classic Thrillers,” Tara Isabella Burton explores these obsessive queer friendships. The worst examples are blatantly homophobic, reducing queer love to narcissistic self-actualization or violence. The best create an ecosystem of desires that more fully engenders this desire to be: “sexual desire, social aspiration and personal identity all refract off one another.”

Tom takes up residence in Dickie’s life, furnishing it with Dorian Gray opulence and chintz that Freddie notices is categorically un-Dickie. “Access to Dickie’s possessions allows Tom to define himself in opposition to them, just as he defined himself in opposition to Dickie the human being during Dickie’s life,” writes Burton. Through this possession, Tom begins to learn what he might want.

Burton inspects the ur-narratives of queer possession, beginning with Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 vampire novella, Carmilla. When Laura’s family finds Carmilla in a carriage crash, they welcome her into their home. Their friendship thickens, and at night she stalks Laura’s bedside. Carmilla entices Laura into her undead world: “If your dear heart is wounded, my wild heart bleeds with yours. In the rapture of my enormous humiliation, I live in your warm life, and you shall die—die sweetly, die—into mine.”

The novella codes romantic seduction as consumption, a desire for total visibility and mirroring, complete reciprocity and monstrous possession instead of a romantic and sexual consummation of love. Burton writes, “Re-inventing himself as Dickie, Tom achieves not just erotic possession but, as in Carmilla, a kind of commingling. He and Dickie are, as Carmilla and Laura were, ‘one forever.’”

In my senior year of college, I took a horror film class. The course took us through a survey of the genre, from Psycho to It Follows, unpacking monster theories as we went. When we watched The Fly, David Cronenberg’s creature feature in which a mulleted Jeff Goldblum transforms into a human-bug, we discussed Julia Kristeva’s essay, “Approaching Abjection.” Instantly, I was obsessed.

“There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being,” writes Kristeva, “directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside, ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable. It lies there, quite close, but it cannot be assimilated. It beseeches, worries, and fascinates desire, which, nevertheless, does not let itself be seduced.”

Watching horror films gives us something to control. We exist in a fragile state, and we constantly need to establish boundaries between self and not-self. Horror films blur these boundaries. The abject reminds us of the facts of our bodies through excretion, secretion, expulsion. Our skin is cut open for us to see. We can only look from behind an afghan on our couch. Otherwise, Freddy Krueger could reach out his bladed fingers and slice our throats.

With horror, we reestablish a separation from earthly rot and the hand of nature. Stomaching what happens on screen, we reify a distinction between us and them, control over what will befall us. The people onscreen die, but we survive.

Gay sex upends expectations, reconfigures the framework of intimacy and demands new definitions. It queers. Tom Ripley never has sex with a man onscreen, never kisses one. Instead, he dares to the boundary—dons Dickie’s jacket, drags his fingers through the bath. I watched moments like these and forgot about them, ignored them, or else I used them to redefine my own separation from Tom. Because the film denies gay sexuality its full presence, it wasn’t so hard for me, scared of how my feelings might change my place in that circle of my friends, to delineate where Tom’s feelings for Dickie diverged from my own. That’s not how I feel. It’ll be over in a minute. The erotic will pass.

The abject manifests when Tom murders Dickie. He consummates desire with blood instead of sex. Assuming Dickie’s identity, he annihilates their boundaries even further. Though Mr. Ripley evades physical, sexual abjection, it dwells in this monstrous becoming.

I could watch Carrie and her pig blood, Pam on a hook in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. I didn’t mind Seth Brundle spouting wings and pus, Regan MacNeil going from twelve-year-old girl to devil spawn. But when Tom gets bolder, when he transforms, I found it hard to stomach. I didn’t watch the movie again for years. Conceiving of Tom as only a murderer—sociopathic, obsessed platonically—I could ignore how queer he really is.

It would take reading Call Me by Your Name three years later to label my feelings for Dickie as romantic—to see obsession as infatuation, a blossoming of desire.

I’d graduated and lost touch with Dickie. After seeing the trailer for Call Me by Your Name— another sumptuous gay drama, Italy, summer, James Ivory decadence—I downloaded the audiobook. I was living in Maine again, employed by our alma mater. At night, I killed time before a class I was auditing by powerwalking through the February night and listening. Mr. Ripley didn’t capture my feelings for my former friend. This did.

The Talented Mr. Ripley came out in 1999. There was only so gay it could be. It mines psychology and sidesteps gay love. My wilful misreading of the film’s sexuality aside, though the film reflected my feelings back to me, I could evade the logical conclusion of the comparison between me and Tom—that I was infatuated with Dickie, romantically—because Tom goes berserk. My closet logic was impeccable.

The Talented Mr. Ripley got me to engage with my feelings about this man in my life, but its blurriness also let me hide. Saying the film was a character study in the effects of “magnetism,” I sought to understand magnetic attraction—not gay love—as the operative force of my life. I looked for stories of bromances manifested. I read about homosocial friendships, listened to podcasts about their importance. Every time I placed particularly high stock in one of my male friendships, I could say it was a yearning for connection my female friendships couldn’t provide. It would take seeing more accounts of queer love—and overcoming the fear of actually touching it—to come to my own understanding. Mr. Ripley, and Dickie, would never get me there. I needed to see magnetization beget sex, not monstrosity. Only once I’d sought out romance did I have something to guide me forward in my own life.

*

I took one step across the line and then wanted to erase the border.

It was during my MFA program. That night, I’d been planning on crashing on his couch so I could go out without worrying about driving home.

He had snuck home from the bar for time alone. I flopped on his floor. In a crossfade, I dictated a story about Carmilla, and under the glow of his string lights I asked if what I felt was real. He took my face in his hands and we kissed.

The couch went untouched after all.

“We may call it a border; abjection is above all ambiguity,” Kristeva writes. “Because, while releasing a hold, it does not radically cut off the subject from what threatens it—on the contrary, abjection acknowledges it to be in perpetual danger. But also because abjection itself is a composite of judgment and affect, of condemnation and yearning, of signs and drives.” So maybe watching these films, we’re bearing witness. We’re remembering how porous our boundaries really are.

*

I revisited The Talented Mr. Ripley a few months into dating my first boyfriend. And this time, Dickie bored me. He likes how Tom clamours for his attention. He takes advantage of it until it gets romantic. It’s the story we know so well, of a gay man falling for a straight man who leads him on for kicks, who gets off on being doted on.

On this viewing, I cared about Peter Smith-Kingsley. Initially eager to superimpose my story with my friend onto the film, I’d completely forgotten about Peter. Tom meets him after murdering Dickie. Peter sees Tom, assumes he lives astride the closet threshold too, and they quickly begin spending more time together. After coming to his rescue during a police interrogation in Venice, Peter speaks with Tom about the gravity of murder, and Tom asks Peter, in the most metaphorical of language, if he too takes the past and puts it in the basement, locks the door, and never goes in. He calls out to Peter, saying, “And then you meet someone special and all you want to do is toss them the key. Say, ‘Open up. Step inside.’ But you can’t because it’s dark and there are demons.” Yet Peter draws closer to Tom. If Tom’s early days with Dickie flicker with the energy of a dynamo pulling him into his orbit, his time with Peter is tender, a moment of grace. In spite of the violence, the film throbs with the potential of them sharing something reciprocal.

Mr. Ripley could never have coaxed out my own realization. It conceals and codes and makes monstrous Tom’s relationship with Dickie, just enough to allow viewers to ignore what’s there. But this time, while I watched, the movie felt so much gayer. In looking for a codex on homosocial magnetism, I’d missed the film’s overt homosexuality. This time, I wanted nothing more than for Peter to get out of this story okay, for Tom to weather acknowledging his attraction so they could be together.

But we’re still in Patricia Highsmith’s world.

On a boat bound for Greece, Peter watches Tom kiss Meredith Logue—a kiss he has to give to sustain his lie that he’s Dickie Greenleaf—and confronts him. But Tom’s too mired in his web, “stuck in the basement,” alone in the dark, to be honest. He lies about who he is. He doesn’t talk about being gay but about being nobody. With tears in his eyes, he asks Peter to tell him “some good things about Tom Ripley.” He stalks to bed, playing with a necktie, while Peter speaks. Resting his head on the pillow, Peter says, “Tom is talented. Tom is tender. Tom is beautiful.” The scene cuts to Tom alone in the cabin, and in voice-over, Peter continues. He assumes Tom’s secrets. Tom has nightmares. Tom has someone to love him. “Mmm. Tom is crushing me,” he sighs once before repeating it in a loving whisper, and for a moment we might imagine the lovers off-screen, Tom turned to Peter, whose delight at this new intimacy is absolute. We’ve reached the precipice for Tom and this border that could be erased. But Tom starts sobbing and Peter chokes, “Tom. Tom, you’re crush—” And Tom’s alone again, in a hall of mirrors. He’s on his ship but will not cross, will not arrive.