What were we obsessed with, invested in, and beset by in 2020? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the issues, big and small. Keep up with this year's series here.

About twice every week, since the summer of last year, I’ve been taking French lessons with a friend of mine who lives and teaches the language at a private institution in New York. She used to teach at the college level but finds children and the pay for teaching the children of rich people more agreeable, and it has more security than what she did before.

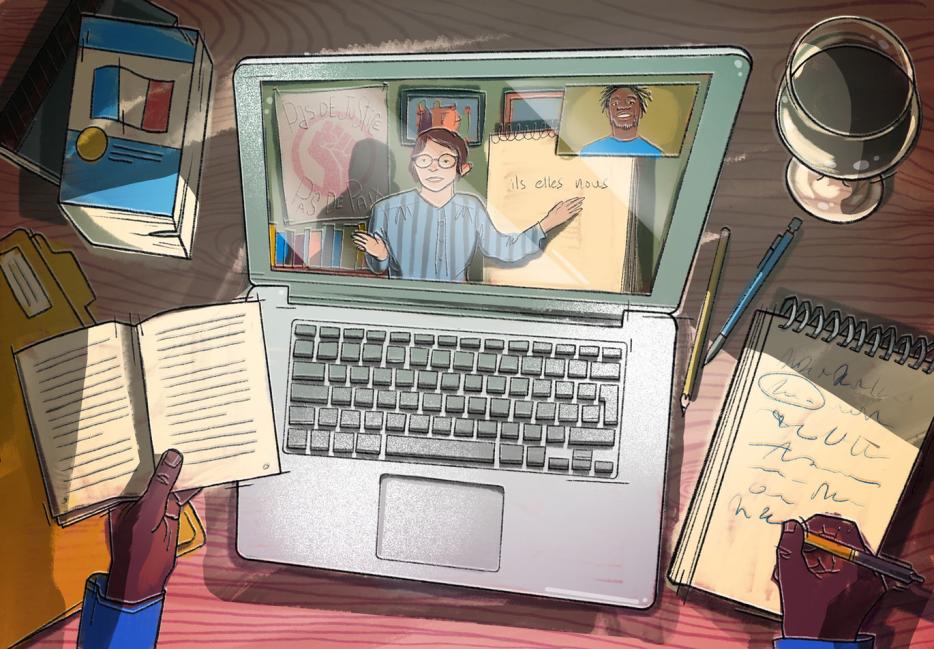

Before Zoom meetings began to totally dominate the lives of people lucky enough to work from home during the pandemic, the two of us were showing up on Mondays and Thursdays, and then Tuesdays and Thursdays, often exhausted from work, sometimes drinking wine, so that she could go over one or two of the lessons that she did with her elementary students and I would struggle and feel like a complete fool over the simple goal of constructing a sentence such as “il fait chaud.”

My drive to learn French began when I went to the Women’s World Cup with some friends that summer. We were mostly in Lyon, but I snuck off to Marseille in the lull between the semifinals and the final. Marseille has pulled on me since I first became aware of it, and that has consistently gotten stronger over the years—strange, maybe, for a city I had only been to once before a few years ago, but thinking of Marseille gives me the same longing I have when I think of the village I came from in Nigeria. It’s not wanting to go there as an outsider, but to return somewhere I belong.

Marseille is a beautiful city, as most cities by the sea and with ancient architecture, large churches and cathedrals tend to be (not to mention Le Corbusier’s city within the city). It seems like a place built for pictures, and it’s no surprise that there is an infinite number of pictures of it online from the prescribed tourist vantage points. Being in the city, though, I still felt the urge to document what I saw and add to that ever-growing collection of images depicting the city from an outsider’s perspective. I walked from Saint Charles station to Old Port, across Le Panier, through Cite Radieuse, to the Velodrome stadium, and then to the Notre-Dame de la Garde, taking all the necessary photos along the way.

The city is also known for its crime—people who heard I was going there offered advice not just on where to visit, but where to avoid. I walked around for days and looked at all those spectacles and spots engineered for a tourist to be amazed at, but I also went to those places that I was told not to go. It wasn’t so much an act of rebellion or thrill-seeking—Marseille is a city of immigrants, proudly so, and I figured that the people in those shunned places were probably people like me, only separated by luck and the cruelty of Western borders. It felt incorrect to think of a city as beautiful without seeing the people who make it possible, those who are often hidden away from the bubble of tourism.

I was right. Walking through those narrow streets in my black tracksuit, I fit the image of many of the people there. The problem was that I couldn’t speak to anyone. So I declared that I would learn French, because I wanted to live there, and I wanted to be with those people, to talk to, learn from, help, and suffer with them.

I made the declaration to myself, but also thankfully tweeted it out. That’s when the person who would become my teacher and friend replied that she would teach me, and when we went on to plan the classes privately, and I asked about the payment, she said that she would do it for free. Naturally, I was suspicious, but it has not come up since, and she seems to enjoy teaching the lessons as much as I enjoy learning from them.

One of the things that makes our French lessons wonderful to me is that they’re built on friendship and kindness. We have a schedule of days, but we hardly ever stick to it. She works full-time and sometimes is just tired from the job. And the same for me. When that’s the case, one of us sends a message to the other asking if we can reschedule, and we do so whenever it's convenient.

Exhaustion isn’t always the reason for missing a lesson. A few times she’s been with friends, or out canoeing; I tend to simply forget the day and time until she texts me about the lesson, a habit that’s only gotten worse with the pandemic. Never has there been any anger or hurt in the changing of schedules.

Kindness and friendship also provide a great foundation when learning a new language, as I have come to find out. I’d taken a few other languages when I was younger, but the last I actually learned was English, and that was as a child. The difference in adulthood seems to be that with less time to simply be around and absorb the language, learning a language like French means learning its rules, solving it in a sense, in order to then be able to thrive within it. That also means confronting some of the absurdities of a language, such as the fact that conjugated verbs in French have different spellings depending on the number of subjects, but when spoken, all sound the same.

Absurdities like that are one challenge, but learning a language just generally makes me realize how difficult constructing a sentence is; as someone who thinks of himself as intelligent, that difficulty can sometimes be frustrating. And I know it would be more frustrating and maybe an excuse to stop if I didn’t have a teacher who laughed at the absurdities and was patient with my struggles. I imagine that the effort to learn a new language is much tougher in an environment that’s not as forgiving as the one we have.

Our friendship deepened after 2019 ended and we began the worst year that many of us have ever lived through. I was in Europe at the turn of the year for my birthday, but came back in early March before travel to other countries was banned. With most of the country going into lockdown soon after, the French lessons suddenly became one of the only times I was able to see and hold a sustained conversation with someone other than my parents.

The world got steadily more exhausting and terrible. Time seemed to move simultaneously at breakneck speed and in slow motion. The longest March of all time turned to June in the blink of an eye, and within that period infections from the virus rose to the point that thousands of people were dying each day. Like millions of other people, I lost my job; I also got involved in the protests and movement against police brutality and racism after the murder of George Floyd, which pushed me to the brink of despair. But only to the brink.

My friend and teacher lived through the horror of New York being the worst-hit area in those early months, and then saw how inefficient and unprepared schools were in moving away from in-person classes and coming up with a plan for remote learning. She also participated in the protests.

Through all of this we kept our lessons going as best as we could. Sometimes we never made it to the French and simply reflected on the disaster of the world that was unfolding—not as a way to understand, but to talk about the impossibility of understanding, the pure chaos of the events, and the truths that were being revealed about the cruelty of the world’s design, and those who shaped and were still shaping it. People were dying, but they were dying because those in power had decided to sacrifice them.

The pandemic and the protests deepened things I knew about the world—intellectually, and from lived experience as a Black man and a person who was poor. None of the evil was surprising, though it was shocking. It is one thing to know something, but quite another to see it played out at a grand scale. Though I could no longer believe in so many myths about the country and its people, the evil of the time also showed me how much effort was needed to fight against it. Still, at the brink of despair, I could never fall completely in—there are too many vulnerable people in this world, too much goodness and joy, to completely abandon it. Our societies may be designed in a cruel and inhumane manner, but it doesn’t necessarily have to remain so forever.

My friend and teacher, as a white French woman, was as rattled by the pandemic as I and so many were, but related to the protests in different ways than I did. Though she was aware of racism, and had written about and researched the history and violence of colonization, there was again a big difference between having a concept of something and witnessing and experiencing it personally. She was swept up in the movement and felt that as a conscious and caring person, she had to participate.

It was a wonder to see her radicalization during our lessons. She went from asking questions about racism and talking in amazement about the stamina of the protests, to joining in with a group of bikers, and then quoting and referencing prison abolitionists. It was a journey that I’m sure she would have made on her own, as an intelligent and accomplished woman, but I also tried to repay her kindness by explaining any concepts and answering questions she had through her transformation.

We continued our lessons until around the election. By then I was exhausted. I had taken on a temporary job as well as a few freelance opportunities, which meant I was working until 9 p.m. every day while still trying to sneak in an hour of French. That, plus the frenzy of the election cycle, was making it so that I couldn’t concentrate, so we paused and decided to pick up after the drama died down. Of course, as has become a given with this year and the Trump administration, despite his loss, the drama did not, in fact, die down.

While our lessons were on hold, I asked myself why I was still learning French—my progress was going slowly, and besides that, the world was exploding every other day. But I enjoyed the time with my friend, and though the lessons weren’t an end to the troubles of the world around us, they were time away from the chaos. At least for two hours a week.

What those hours really provide, though, is the possibility of a future. During our French lessons, I can imagine a different me. I can imagine a me who knows French and can walk through the streets of Marseille talking to the people. I can imagine a world that isn’t this one—not a world before, not a dream to return to the previous state of things, but of salvaging the good for a better tomorrow.

This year has been filled with so much violence and death, so much evil and grief as a consequence of it. Some days it was damn near unbearable. But I have changed—I’ve grown stronger in my convictions about the sanctity of life and the need to protect the most vulnerable, and I’ve seen my friend and teacher change in the same direction. I’ve been grateful for the possibility of learning French, for the little spaces of time each week where I can get on camera and fail at basic sentences and rant about the ridiculousness of so many words sounding the same. Because within all of that failure, in a year unlike any other, is the chance of becoming something new.