What were we obsessed with, invested in, and beset by in 2020? Hazlitt’s writers reflect on the issues, big and small. Keep up with this year's series here.

January: Disco Elysium

The first video game I play in 2020 is so transcendentally good that it makes me want to spout wild claims about Art and Meaning, which normally only happens to me after two glasses of wine. Disco Elysium is a game about a detective who has lost his memory. It's also a game about a failed revolution and a failed marriage, about communism and fascism, about ideals and loss and earning the respect of the impeccably voice-acted Kim Kitsuragi. Also, cryptids!

It's so good. I won't spoil the ending but it had the effect of making me jump up from my chair and pace wildly up and down saying things like “eucatastrophe” and “sublimity” and other unspeakable bits of litcrit wank. The game is a very smart, very powerful exploration of identity under pressure.

Playing Disco Elysium gives me the feeling of standing outside the world looking in, which is backwards from my usual experience of video games. Normally burying myself in a game is about standing inside the world and beating frantically on the doors and windows, let me out.

I am going to play a lot of games this year.

February: The Witcher 3

Since its release in 2015 I have played The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt for an unconscionable length of time. I then wrote and published two books about how much I like the idea of a gruff old monster hunter with a heart of gold. However, I have not played the downloadable content where our gruff hero goes to fantasy France; this I have only experienced via a French friend sending me strings of texts screaming about the accents (Touissant, pronounced too-SON).

I decide it's time. Obviously, I have to replay the whole game first in order to get to the fantasy France DLC. (I don't.) This takes me three weeks, after which I no longer want to play The Witcher 3. It turns out it is possible to play your favourite game to death. Touissant remains a mystery.

March: Two Point Hospital

In March, per government advice for people in at-risk categories, I start working remotely. And when I'm not working, I play Two Point Hospital.

This is the kind of game my brothers used to make fun of me for: you don't actually like playing video games, you like optimising a spreadsheet with a soundtrack. In Two Point Hospital you are a hospital administrator aiming to squeeze as much money as possible out of your patients as you diagnose and cure their jokey diseases (Freudian Lips, Jest Infection, Mood Poisoning). The trick is to invest in training up specialist staff.

I get as far as the level where you have to manage a series of virulent epidemic outbreaks, and abruptly stop playing.

April: Sunless Skies

Everyone else is playing Animal Crossing this month, so perversely I start something dark. I have been dipping in and out of Failbetter Games' Fallen London universe since it was just a rather good browser game back in 2010. It has the dubious honour of being possibly the only steampunk fantasy I like. (No, that's not true, there's also Girl Genius.) Otherwise I tend to have killjoy opinions on most fantasies of this type, including but not limited to, “You get most people were poor, right?,” “What are these twenty-first century Americans doing in Victorian London?,” and, “I don't expect perfect prose pastiche but please for the love of God read one book that was actually written in the nineteenth century.”

The prose in Sunless Skies—a game where you drive your flying steam engine from port to aerial port pursuing wealth, fame, and secrets—is remarkably good: not a flat Dickensian pastiche, not jarringly modern, but satisfyingly intentional in how it builds its late-Victorian atmosphere. I entertain a brief feverish fantasy of applying for a writing job with the studio and learning all their tricks.

This is also a very good game for escaping from current events. I get a solid seventy hours of distraction out of it.

May: Final Fantasy X

Final Fantasy X was my very first video game. It was 2002 and I had no frame of reference for the Final Fantasy series, so I had no idea what I was getting into. It features some very bad voice acting, a handful of beautifully animated FMVs which in 2002 were unlike anything I'd ever seen, several infuriating minigames, and a completely bonkers plot which, the first time I played, made me cry. Downsides of being thirteen: you are thirteen. Upsides: you are able to experience profound emotions about how tragic it is that your video game dad has turned into an evil eldritch whale being mind-controlled by God.

It's been remastered for the Switch, so it's time for my first replay in nearly twenty years (oh god the passage of time!). The art direction holds up—this twenty-year-old game looks a lot better than some modern releases, and the final trip through the ruined city full of ghostly demon soul-sparkles (don't ask) is as beautiful as I remember. The score is excellent, the plot is still bonkers, and the minigames are unbearable. I get as far as the last dungeon and realise I left my motivation to grind through boring fights for hours somewhere between here and 2002. I do not defeat my eldritch whale deity-dad in battle, or save the world from an endless cycle of destruction.

Wouldn't it be nice if you could change the world by just doing battle with a whale, who is your dad, and also God? This is the real enticement of an RPG: imagine being able to do something.

June: Starbound

Starbound is Minecraft for people who find 3D gameplay stressful (me). It's very cute and the soundtrack is nice. I fully upgrade and decorate my spaceship and then lose interest.

July: Picross Luna 2

Picross Luna 2 is a free iOS game, poorly translated from Japanese, where you solve puzzles by counting squares on a grid. The soundtrack is about ninety seconds long, and loops. Every time I complete a puzzle, the game shows me an advert for a tool to remove earwax.

I play it for two hundred hours. I see fifteen by fifteen grids when I am trying to fall asleep. My hand hurts from the motion of tapping and dragging to fill in squares.

The doctor doubles my antidepressant dosage.

I stop playing Picross Luna 2.

August: Mass Effect

At this point I decide it's time for something I know is good. I wish I had realised back in August that they were about to announce a remaster of the Mass Effect trilogy, the best thing Bioware has ever done, because then I would have waited to do this replay of the slightly-clunky but wildly effective first game from 2007.

While I am playing the first section on the Citadel I muse on how much has changed since 2007, when somebody okayed the plotline where the first thing that happens when you go to the Space UN is you get involved in the affairs of a sexy alien courtesan who finds you fascinating for no reason and is never relevant again. It's not that I object to sexy aliens; it just seems very clear, as I watch this character embracing my Commander Shepard, that no one involved in writing this story thought seriously about the possibility of a female player. It's not bad, but it's very… male gaze.

The big Act Three villain reveal still absolutely rules, though.

September: Crusader Kings 3

Nothing better encapsulates the Crusader Kings 3 experience than this: my first character, in the course of becoming High King of Ireland, develops the Lunatic trait. His wife dies, so he decides to stuff her corpse and keep it with him always. This gives him a penalty to his diplomacy score (the corpsewife makes people uncomfortable for some reason) but prevents him going insane with grief. Later, his great-grandson unfortunately has both the Sadistic and the Just traits: he loves to torture people, but he feels terrible about it afterwards. He quickly develops depression. “This is you,” the game tells me under his character portrait, “though you don't always feel like yourself.” By the end of his reign he has banished his entire court except for a couple of daughters and does not have enough people left even to fill the key positions on the royal council. I feel a terrible pity for this awful monarch, presiding over an empty palace, brooding on his self-loathing.

N.B. that at this point I have barely left the house in six months.

October: Hades

In October, in a move critics are describing as “a bit on the nose,” I start playing a game about being trapped eternally in hell.

Hades is set in the Underworld of Greek myth, and so it faces the usual challenge of Greek-myth-modern-audience, which is what do we do about all the, you know… The incest issue is dealt with by making some key Olympians foster siblings rather than actual siblings (nice dodge!). The sexual violence is dealt with by either a) never mentioning it or b) rewriting it into a consensual love story. Fair enough: who wants to play a game where nearly every male character is an unrepentant rapist?

The uncomfortable bits of Greek mythology still lurk in the background, just offscreen. The plot of Hades is all about second-chance love stories—Hades and Persephone, Orpheus and Eurydice, Achilles and Patroclus. I find Achilles the most compelling of the lot, but it is fascinating to watch the dialogue tie itself into knots around his story—rage, loss, grief, death—without even once mentioning the whole “temper tantrum because of the status implications of my commander kidnapping my sex slave” issue. This is a flattened-out Achilles, straightforwardly sympathetic. Being a ghost seems to have calmed him down. Or maybe he's just depressed.

I spend a lot of time thinking about katabasis stories, descents-to-the-Underworld; you go into the dark, and you find dreadful answers there. The model is the Odyssey, where Odysseus visits the Underworld and learns from the shade of the prophet Tiresias, you will never be done journeying; from the king Agamemnon, even home is not safe; from the hero Achilles, the glory we fought for was a terrible lie.

Hades is a katabasis in reverse, with the mood reversed too: the answers it tries to give you are happy ones. Its best moments are the handful of times you manage to escape to the surface and walk through a snowbound landscape as the music changes and the sun slowly rises. Once I complete the main plotline I realise with outrage that the game is not going to show me this sequence anymore. Instead I just get a black screen and few words from the narrator each time I beat the final boss. The loss hurts. I stop playing.

November: Monster Prom

Apparently, it is possible to play games with other people as a social activity, and not just fixate on them by yourself as a coping mechanism?

Monster Prom is a dating sim set in a high school for monsters. It's cute and funny and it has a surprisingly good collaborative multiplayer mode (help your friends win their ideal monstrous date!). I play it with three friends whom I haven't seen in months and it's… super nice actually? Friends are good! Especially when you have spent 2020 slowly losing your mind!

December: RingFit Adventure

In the spirit of “doing comparatively healthy things with video games,” I round out the year with a lot of Ringfit Adventure. This game cunningly weaponises the mechanics of an RPG (increase your level! unlock new outfits!) to force me to do an unholy number of squats. The plot is weirdly compelling despite consisting mostly of exercise puns. I grow genuinely invested in the totally PG but somehow deeply uncomfortable (sexual?) tension between my animatronic resistance ring genie and the large sweaty dragon we are fighting.

It turns out every single person who told me that regular exercise would improve my mental health was right. Infuriating.

***

I wish I had something pat to say about my year of playing video games. For most of 2020 I could not focus on a page for long enough to read a book, or sit still for long enough to take in an episode of a TV show. Games were my only escape.

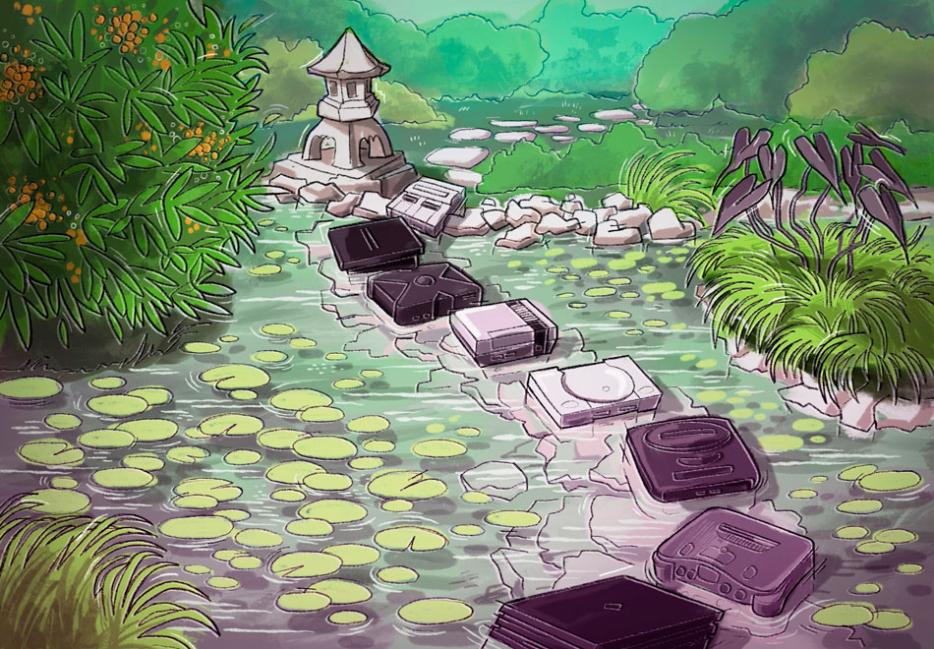

I think about how broad the medium is, and how many things it can do—from the undeniable high art of Disco Elysium to the impressive-in-a-horrible-way power of Picross Luna 2 to make me willingly watch approximately seven hundred repetitions of a short video about earwax. All media—all art—aims to have an effect on its audience, but the video game is unique in the way that controlling and directing human behaviour is built into the form. The player is complicit. Whatever happens (eucatastrophe, earwax, etc.) we have only ourselves to blame.

Depression gaming—and let's face it, this was a year of mostly depression gaming—can turn these illusions of control and agency into a lifeline. Still, every so often the words of an old friend I no longer speak to come to mind: are you actually having fun?