“John has a theory that everyone is either a squid or an eel,” writes Elisa Gabbert in the final essay of Any Person Is the Only Self (FSG Originals). Baby squids are born entirely formed, “teeny versions of their later selves,” while eels, on the other hand, go through radical changes, and are hardly recognizable from their beginnings. “In part to test my squidness,” Gabbert takes up rereading the novels of her youth—Updike, Salinger, the works. Satisfyingly, most of them hold up—more or less. (I read with relish as a fellow squid who also felt that Rabbit, Run was my favourite book at eighteen and have since stared warily at it on the shelf.) It’s reassuring to find that, at least sometimes, the version of myself who “only knew what she knew” wasn’t wrong. Rabbit really was kind of interesting, if flawed. Convictions can hold, loves can persist; we have always been, largely, ourselves. This note of relative stability, with space granted for a Russian doll–like layering of experience, offers a serene conclusion to a book that takes up the fundamental shiftiness of the self.

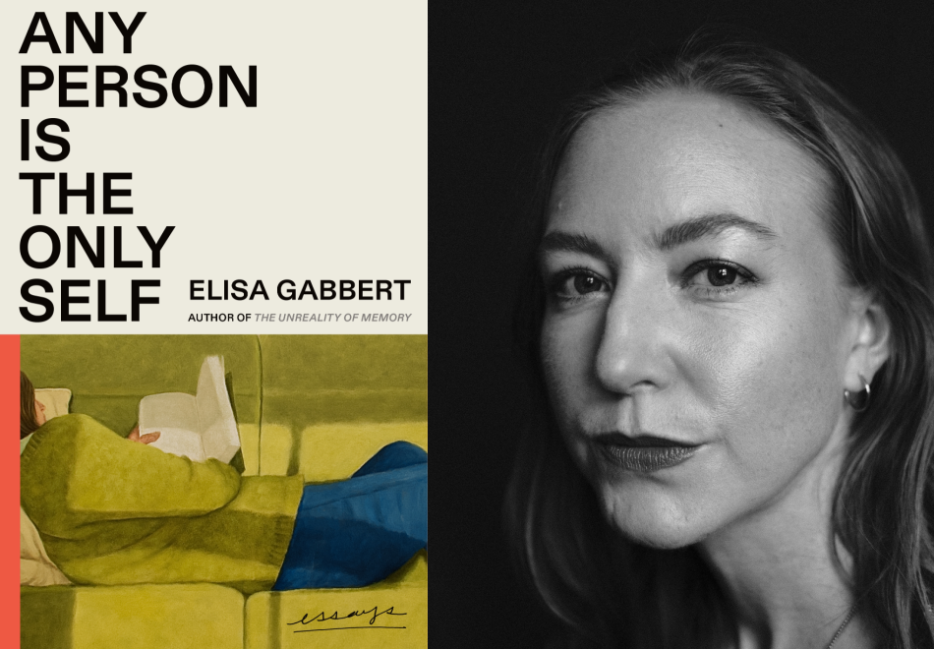

Internal disunity is a core obsession. An essayist as well as a poet, Gabbert has published two previous essay collections, The Unreality of Memory and The Word Pretty, as well as four books of poetry that include Normal Distance and The Self Unstable. Each tussles with our porousness, our penchant to self-create and self-forget, and the impossible-to-pin-down-ness of inner life. They relish the way evolving contexts and encounters can shake one’s stability—poke the squid, if you will.

Any Person’s sixteen essays about a life lived with books point to the several selves and verisimilitudes that exist within any one person. Throughout, Gabbert considers the selves that appear both in her writing and in contact with other people’s; the ones who emerge in isolation, in proximity to others, in childhood, in one’s time, in certain rooms, across the thresholds of memory and mood, at the height of an experience, and in its aftermath. Such selves exist in harmonious mutual denial, if not chummy collusion.

It’s no coincidence then that Gabbert’s essays are so often concerned with the work of reading. Flipping through her oeuvre, it is clear that there is no better way to disrupt the self than to immerse it in the life-worlds of books. Any Person theorizes on reading and offers snatches of Gabbert’s mind in action, preoccupied with the worlds of writers like Rainer Maria Rilke, Sylvia Plath, and Leonora Carrington. In her signature prose style—analytic, unpretentious, humorous in a knowing way (aware, as in Terry Castle’s quip, that “Pathos could be turned into Bathos”)—we experience her mind bending, conceding, rearranging, complexifying. We step into the room with her.

In the end, it seems our commitment to any one self or vantage point is akin to our investment in the reality of any one novel. Still, “I love when a piece of fiction insists that it’s true,” says Gabbert. “Inside itself, it always is.”

I corresponded with Gabbert in late May, shortly before the book’s release. We spoke lots about reading, among other things.

~

Rachel Gerry: When you’re a big reader, it’s not uncommon to be asked if you’re a writer too—the subtext being: it would be strange to devote so much time to reading for its own sake. Any Person Is the Only Self takes reading incredibly seriously. You’ve written on reading before—every December, you publish a list entitled “Every book I read in [x year], with commentary.” How did you come to write an essay collection on the subject?

Elisa Gabbert: It was somewhat a return to a comfort zone. My first book of essays, The Word Pretty, was in a similar mode, lots of personal writing about writing and reading with other life stuff mixed in—dreaming, crying—a kind of writing that comes very naturally to me. The Unreality of Memory was more “serious” work, and more difficult work, because I wanted to be taken very seriously. I remember telling my friend Catherine that, in those exact words. “I want to be taken very seriously.” I’d forgotten about that specific desire, until this moment. It was exhausting as a project, soul-depleting. Always after I finish a book, I’m sick of that mode, sick of myself in that mode, and I want to do the opposite, partly as a way of moving past and away from it. So now I find I’m itchy for more immersive research-driven work again, or maybe something formally unfamiliar and thus uncomfortable. Discomfort and comfort can both serve as good distractions, I suppose, from the default self.

There’s a passage in one of Any Person’s essays, “Second Selves,” where you note, “When Sontag read Gide’s journals, she identified so deeply with his thinking, she wrote, ‘I am not only reading this book, but creating it myself.’” Reading can offer an experience of communion: a synthesis can occur when the thinking self, or internal monologue, merges with the author’s. Is this an experience you chase? What would you say you’re looking for in a book as you travel through sixty or so a year?

“Communion” is exactly the word I would use. I love finding a writer who thinks enough like me that I feel fast fondness and kinship—but not so much like me that I feel…threatened, I guess? It’s a bit like real-life friendship that way. You want to agree with your friends a lot but not all the time; you want to learn something from them and be surprised. There are times when I’m reading and think, of some move, a first sentence, or a certain transition, That’s exactly what I would have done. I like it most when that happens with the dead. This sense of recognition isn’t really a requirement, though. I love starting a book and having instant trust in the author, in their total authority over the text. (Authority—my god, the word comes from author!) I love the sense of a writer having thought about anything really deeply.

The dead! So Rilkean. There is death in life, etc., etc. It’s interesting to think of the novel as a kind of meeting place for that exchange.

When I’m reading my contemporaries and the writing sounds like me, I can feel kind of trapped, like we’ve all just been brainwashed by the same web pages. But when it happens with the dead, I know it’s not just some zeitgeist thing. It makes you realize there’s real continuity in human consciousness. And yes, it’s supremely Rilkean to think so: the dead live on in us. Maybe reading is always a little bit occult.

Back to this idea of communion. The union between self and text is not always purely pleasant. In “On Jealousy,” you lament the way your re-obsession with Plath emerged alongside others, as though out of “some manifestation of collective consciousness.” It seems you’ve been spooked off writing on Plath, fearing redundancy. It’s surprising, then, to arrive at the next essay, a meditation on Plath via Red Comet, Heather Clark’s 2020 biography. It felt like a humorous nod: So what, who cares, I’ll write about Plath anyways. But it also felt like a different self was speaking here, maybe a more earnest self, one who couldn’t help but see the value in working it out for herself. I wonder if you see an essay collection as a kind of tension-space between selves, each essay a door—the way you describe Malte Laurids Brigge’s wardrobes—“portals to the other self, the mask or the costume that permits transformation.” Essays as footnotes to other essays.

A “tension-space between selves” is so good. And footnotes to other essays, yes. They live in the same book because they’re interconnected. But also—I think we’ve gotten kind of weird about reading books like reviewers, in the age of the internet. I saw a bit of a video once where this aspiring book influencer delivered this pained, extended apologia for not finishing an essay collection, like it hurt him so much not to finish the book but he just couldn’t. And I thought…most people don’t finish most books? This is not a crime—it’s not news in any way. People don’t even need to know about it. We own many books that I’ve only read parts of, and I love them just the same. I certainly don’t hold anything against a book because it didn’t demand to be finished quickly. And I don’t expect most people to read Any Person cover to cover, in order, in full, etc., unless they want to. I tried to make it work that way because I do often read books that way, of course, lots of people do, but I also think the essays stand alone, and I also am not trying to hide that I sometimes return to the same subjects with different perspectives or new ideas or more knowledge. I wrote these essays over five years, and they’re not arranged chronologically. They’re arranged by mood.

Mood leaves room for a kind of spontaneity. It feels consistent with Any Person’s appreciation of anti-curation, the recently returned shelf at the library. Randomness emerges as the missing ingredient, the defence against superfluity, the guarantor that any person is, in fact, the only self. Is it in finding the flukes that the real work of writing a book or mapping a collection happens?

You know, whenever there’s something I want to talk about with [my husband] John or my friends all the time and none of them seem very interested, I usually end up writing about it. If you find yourself fascinated by something objectively “boring” or trivial on the surface, there’s probably something useful, something animating there. The last time I clearly remember this happening was with a YouTube video where this guy with a professed phobia of the ocean (“thalassophobia”) filmed his own reactions to various photos and video clips of scary underwater stuff. I watched it several times. And I ended up writing an essay about fear—about, in particular, the ways we intentionally provoke our own fear—because nobody wanted to talk about it as much as I wanted to think about it. But you’re getting at something more than subject matter, I think. I’m not entirely sure how we recognize, as writers, which of our thoughts are interesting. Or how we can make them interesting to anyone else. But without some kind of intuitive sensibility here, some way of sensing what’s worth saying in public, there’s no voice, no authority, no charisma.

Meaningful adjacencies are all over Any Person: the journal as paratext to the life, the energy in being physically near other people, the reality and unreality of fiction. Does the best thinking arise between texts, between worlds?

Comparisons and pattern recognition are part of what the brain naturally does when you’re really awake and alive, I think—that’s how I feel when I’m writing, on a good day, like I’m fully alert and everything is activated. Old memories surface; strange, unexpected connections make themselves known. I used to know someone with epilepsy who told me that sometimes, after a seizure, he felt like everyone he saw looked familiar. I find that fascinating. It suggests that “meaningful adjacencies” might be a kind of error, a useful error. When I’m starting an essay, if it seems to only be about one thing, there’s often a kind of inertness to it. But if I bring two or a few things together, in a circle of heightened attention, the ideas start to do things to each other—they start to get more complicated and interesting. Just putting things into proximity creates the conditions to generate meaning.

You are a poet as well as an essayist. As a young reader I once understood poems to be sort of like tiny non-fictions, and it helped me ease into poetry, a form I’d previously found challenging. Is there a kernel of truth here? A kinship between the poem and the essay?

It might depend on the poet—I’ve always found poems to be closer to tiny fictions. Even if the content is “true” and from my life, the poem is a fictive, performative way of saying it, a formal guise that nullifies the question of whether it’s “true.” That question just doesn’t pertain. So what is the overlap? In either case, there’s usually something I want to say. I may not even know what the thing I want to say is until I’m in the process of writing. But I know that it can’t stand alone as a thought, so I have to Trojan-horse it into some larger structure. It needs some kind of context, an apparatus that surrounds it and supports its meaning. As the architect Robert Venturi says, “contrast supports meaning.” Somehow the thing becomes the most important part of the essay or the poem, even if it feels quite surprising that it’s there. There’s usually a stark kind of undeniability in the language of this thing, like it couldn’t be said in any other way, and the context makes the way of saying it possible.

You refer to the way poets’ novels are often “messy and strange transmutations of life,” a little disproportional, a little “wrong”—in a good way. Is there such thing as a poet’s essay?

I want to say it’s not as easy to generalize, because essays are so much easier to write than novels. If I’m brutally honest, most of the time I wouldn’t want someone to read one of my essays and think, “A poet wrote this.” Why is that?! I am a poet! But I’m equally an essayist. I guess I don’t want people to think of my essays as some kind of side project. But putting that aside, there’s a genre I like that we could maybe call the poet’s essay: a book-length project in fragmented prose, which might be packaged as essay or memoir or fiction, that engages in a meaningful way with breaks or other poem-ish formal gestures and structures. (I just said essays are easier than novels, but I also think fragments are harder than they look.)

Is there a novel that’s taken you so far out of yourself, been so engrossing, that it’s been strange to return to yourself, to reality?

I think it was easier to get that engrossed in a novel when I was younger. I remember absolutely falling into the world of The Secret History, but I was only twenty-three when I read it; I don’t know if it could have the same effect now, like these annoying, overly developed critical faculties are getting in the way, like I’m always comparing books to other books and introducing this descriptive distance. I really crave that envelopment effect though, which is a way of wanting to be young again.

There is always the problem of what to read next—and what to read when. Like you write in the final essay, “You can’t wait to read everything till you’re wiser, nor can you already have read everything once.” There’s the ill-fated experience of continuously picking up the wrong book. And there’s the seeming urgency of all the books that need to be read, both new and old—an inkling that one’s self couldn’t possibly be complete until they are. Do you have a system, an ethos? Would you leave us with any readerly advice?

I think we need tension between freedom and structure, or freedom and obligation, to be happy. I mean happy in the fuller sense—over days and years, a life well lived—not just entertained in the moment. So when I choose what to read, I’m always seeking balance, or correcting what feels like an imbalance. In an ideal world, every single book I read would be a mind-blowing experience, thoroughly delightful and enriching in every way. But that’s impossible, because some books have a tedious or unpleasant stretch to get through before they can blow your mind. Which means you have to stick with some tedious books to find out if they’re going to be great in the end, and a lot of them aren’t! You also can’t force yourself to finish every book you initially find tedious; you could waste years of your life that way. At the same time, if I read a novel that feels a bit cheap or breezy and doesn’t make me underline or think about anything, that’s a tick on the “less happy overall” side. I’m basically just listening to internal signals, very much like “am I full or not”—am I enjoying this enough to give it thirty or a hundred more pages or am I starting to fantasize about faking my own death? And if I read a few books in a row that are in any way similar (too many recently published books, too many Americans, etc.) I look to other categories. But none of this is strictly systematized. Loosely, I have a few books in mind that I want to read soon. I’m almost always reading some fiction, some nonfiction, and some poetry. I don’t plot anything out too carefully. Books can cut in line. If there’s something I’ve been wanting to read for years but the first couple of pages don’t strike me, I put it away to try again later. It’s better to wait until the book is ready for you.