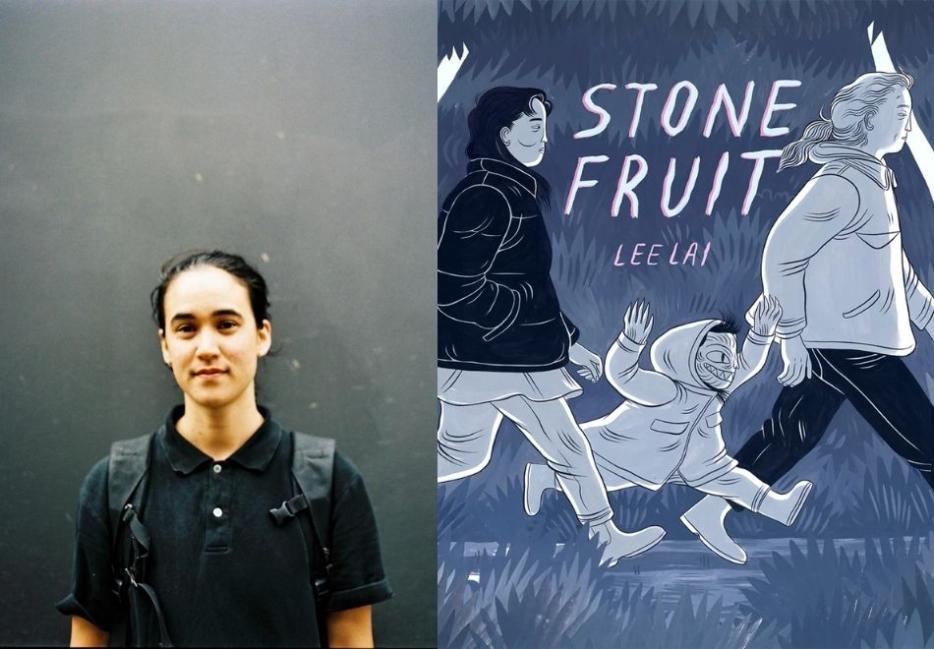

Our relationships are different now. They’re careful, scheduled, six feet apart, and nothing like the ones in the opening scene of Stone Fruit (Diamond Comic Distributors). Three monsters—two adults and a child—tear through dense forest, chasing a white dog with wild, dangerous glee. Nothing holds them back as they roar and sing, covered in mud and grinning. There is much to love in this graphic novel but—if for no other reason than that it reminds its readers of a time less troubled, less full of worry—these first moments of Stone Fruit are a gift.

But the two adult monsters, Ray and Bron, are on the verge of breaking up. The only thing keeping them together is their biweekly play date with Ray’s niece Nessie. When the situation becomes untenable—not helped by Ray’s sister Amanda’s hostility—Bron leaves to reconnect with her family. Beautiful blue-gray tones give life to the relationships Ray and Bron hold dear, even as they change, or grow, or end.

Immediate and melancholy, it’s those relationships that form the heart of the story. They are undoubtedly messy, but they are real and whole and—after many months of quarantine—they have been missed. What a joy, then, to get to meet with Lee in person, perched on a sun-warmed fire escape. Meeting someone new, talking and laughing in a moment of shared companionship: that, too, is a gift.

Alyssa Favreau: A big part of the story is this idea of queer family, of chosen family, and how it plays out in Ray and Bron’s relationship. Why was this the story you wanted to tell?

Lee Lai: Well, I am a homosexual in my twenties [laughs]. Something most of us tend to talk about a lot is the idea of chosen family: the idea that bio families tend to reject queer and trans people and so they go and find their own. But, at least in the stage of life that I’m in, people talk about it idealistically and with a lot of vigour and energy, and then end up struggling with what that actually looks like in practice. Ray particularly is very energized by the idea of hustling forth from what wasn’t satisfying about her biological family and creating that with Bron. I wanted to do [chosen family] in a way that doesn’t just shoot it to shit, because I don’t think it’s a useless idea, but I think it’s more complicated and difficult than me or my friends initially thought it was.

The book focuses so perfectly on all the different relationships: Bron and Ray, each of their relationships with Nessie and with Amanda, Bron with her parents and with her sister Gracie. They’re all complicated, regardless of whether they’re biological or chosen, and I’m interested to know more about why you never privileged one type of relationship over another and refused the easy answers.

I don’t think I’ve found easy answers yet. Maybe when I become an old person—if I’m so lucky—I’ll have some easy answers. Five or ten years ago I would have been more interested in the answer as a means of getting to where I want to be, but ultimately I make comics and I’m surrounded by homos and I’m so pleased with that. I’m essentially where I wanted to be. It’s more complicated than I ever could have imagined in terms of creating and maintaining healthy community and healthy relationships, and I imagine it only gets more complicated, but hopefully we get more skilled.

I don’t know how you manage to be both bleak and hopeful.

I feel very hopeful! I really believe in all these things, and the mess is part of what makes me believe in it. I have a rule for when I’m writing characters, which is “no villains, only messes.” No one can actually be a full villain and, if we’re willing to focus in enough, everyone’s bullshit and everyone’s mess is something that can be empathized with.

It’s a bold move to have the central couple of your story spend most of the book apart. Is that always how you imagined it?

Yes. I wanted to write a story about a breakup. Initially, it only followed Ray after that part, but I showed the first two chapters to Eli [Tareq El Bechelany-Lynch] and they were like, “What happens to Bron? I’m interested. It’s weird that you just drop this character off into the suburban WASP-y wilderness and we don’t see her until she comes back.” The structure that became this split, parallel situation didn’t happen until later. And it became much more satisfying when it did. For me to write, anyway.

And to read. The way the two narratives work together is one of my favourite parts.

It was a challenge [laughs].

I often find that, when I’m thrown into a couple’s story at a point where they’re having problems, there’s not enough there to make me invested. I end up thinking, “All I’ve seen is the problem. You should just break up.” But, with Bron and Ray, I immediately believed that they had been good for each other and that I should be rooting for them. I’m not sure how you did that, but maybe you can reveal some of your magician’s secrets. How did you decide how much of their relationship to show?

I did, for my own purposes of what I wanted to figure out emotionally, want to show a breakup in which both people really care about each other—that’s not a question. They really love each other, and that’s not enough for them to figure out their problems and stay together. I’m also a big supporter of breakups. For the sake of growth and for the sake of people changing and thriving. Breakups can be really important. I wanted to show a breakup that isn’t about the relief of getting rid of someone. That people aren’t dispensable after the romance is gone but that sometimes, especially when people are bringing a lot of trauma to the table, things can’t work out in that way. But I feel like I’m rooting for those two. They both really care and I want them to both be okay. But that comes first before the relationship does.

Fine. I mean you’re right [laughs]. At one point it’s Ray’s sister Amanda who says that it’s “foolish to put all your belonging into any one person.” Who do you think is most guilty of that?

It depends what timeline you’re looking at. In my understanding, Amanda did it very intensely in her relationship with [her ex-husband] Dave, who’s not in the story but his presence is felt.

It definitely comes through in the way she reacts to Ray and Bron’s relationship.

Yeah, her prickliness, her assumptions about the other relationship. And she does it in a way that is less relatable to me: the very heteronormative, nuclear, two-parents-and-a-child vibe. But I think everyone has their own separate reasons for putting a lot of hopes into one other person. I think that’s also Nessie. She’s bearing some of that weight between Bron and Ray—the ways in which they’re kind of relying on those play dates to feel something, to feel some levity. I think they’re kind of all leaning on each other in different ways because they all have completely different needs for it. I don’t think they’re comparable.

The intergenerational relationship with Nessie is a real highlight. She is such a beautiful presence in these characters’ lives and, because of that, it was so frustrating to see Amanda’s queerphobia manifest in such a “What about the children?” kind of way. How did that find its way into the story?

Amanda, at the beginning of the story, when I started writing it, was more detestable than she became. I think I started liking her much more as I got into the later chapters and she and Ray started spending more time together. The fact that she’s somewhat jealous of the magic and the fun that Bron and Ray can have together was not what I wrote into the story initially. My friend Tommi [Parrish] gave that suggestion, [that] as a burnt-out single mom, it would be a kind of obvious step from there, and that that would be informing some of the ways in which she’s bitter and nasty.

It felt very realistic.

It helped to soften the character a bit and make her less of a villain. I was more interested in having her go from hateful and judgmental, and somewhat homophobic, to having more empathy and understanding for Bron. But I didn’t understand what her motivations were until they broke up. I don’t love showing homophobia and transphobia in stories. I don’t want that to be what it’s about, and I don’t plan on doing that much in the future, but I think I did want to show the softer side of what that can look like when it still is wearing someone down. There’s the more extreme version of Bron’s family, which I tried to show less even though it’s implied, but I think the ways it plays out in someone like Amanda is more familiar to my life, and harder to argue with. Or it’s got its claws more tangled up in interpersonal difficulty rather than it being about homophobia in a more flat way.

And even though there’s a lot of concern about Nessie and how she’s dealing with the turmoil around her, she had a little cameo in a New Yorker comic that you drew, and she seems fine.

Full of life and questions. That was the first version of those characters, actually. That was just when I wanted to write about aunties and a gay kid. Or a weird kid, I guess. Maybe she’s gay. I’m pretty sure she’s gay.

She’s got good influences.

But I wanted to write her because I wanted to show queers hanging out with kids more. Some serious wish fulfillment.

I want to talk about the characters’ monster personas. They’re such a visceral, visual element of the story when Nessie, Bron, and Ray go to this “feral and screamy” place. Was that an element you had in mind from the beginning?

Yeah, that was my effort to try and draw more freely and have a bit more fun while drawing. I found it really hard to draw the monsters and make it feel natural in my hand, but I didn’t know how to draw those play scenes without doing that, without creating monsters.

It would have been so easy to have this couple bonding over a child in a way that’s nurturing in a settled, domestic way, but instead, you see Bron and Ray become wilder, access less controlled parts of themselves. Where does that come from? Why does Nessie in particular make them freer?

I forget how to be a child. I think I was a very fun kid, but I grew into much more of a serious adult. And I miss that. Queers in general are really good at accessing play as a way of pushing out of the parts of their lives that are heavier. I think queers tend to make great carers for children, because they’re often able to interact with children in a way that isn’t condescending, by thinking about the ways they would want to be interacted with if they were a child, remembering what it was like to be a strange beast of a child. Children are fucking weird.

[Laughs.]

They’re so weird! I think it helps to have mindsets in which you’re not projecting assumptions onto children. And I think folks who don’t want to have assumptions projected onto them tend to be better at handling and encouraging the strangeness of children, and also enjoying that.

Imaginative play is pretty consistently present throughout. You have it in the play dates but you also see it in Amanda and Ray adopting happier personas to help process grief. And queer family-making also is this act of radical imagination, a way of manifesting something that didn’t previously exist. It seems like that line between the real and the imagined is always in flux. Was that kind of magic realism something that particularly spoke to you?

I tend towards wanting to make work in order to process feelings. I was just chewing on these heavy ideas of trauma and conflict in relationships. Those things are interesting and meaty and therapeutic to figure out in comics, but I want there to be some levity. I want the story to have energy and momentum, for there to be play. I think back on some of the heaviest points of my life and those were also times in which I was laughing so hard I was crying. I think there’s a point where, when someone’s under pressure, everything becomes hilarious and ridiculous. I want those two things to be blurry in stories because they are in real life.

I initially read this as a self-published first chapter. What was it like to see the project cross the finish line?

I got really lucky because the first version was just a script. I’ve never done that before. I’ve mostly just written bursts of dialogue and pencilled them out in tandem. This was the first time I’d planned it quite laboriously beforehand. It still did not go to plan. It never does apparently.

I wrote it in a scriptwriting class, and it was horrifying because it was the first time I’ve not had pictures to support the writing. There were a bunch of people workshopping the script, reading it, and telling me that all these characters sound the same, and they don’t know what’s actually happening, and maybe this bit is boring. Which is great! It’s so helpful getting edits. I need a lot of eyes on a project and so it was really great throughout the process to have people weighing in.

Mostly I just want people to feel whatever they want to feel for this book. As long as they’re feeling something and they get from the first page to the last page, then it’s done its job. One thing that was kind of a breakthrough was seeing every single project as enabling the next. As a practice for the next thing. What allowed me to finish this was to not think about it as a product. It’s very cool that it’s being published and I’m very excited. Now I have an agent! But if I had known that from the beginning, I never would have finished it. It would have psyched me out intensely. It was a really good experiment and exercise in long-form, and it’s taught me enough to do it again.

What more can you ask for?

It’s very exciting.

I don’t have a sister, so I’m curious to know why you chose to foreground that type of relationship.

I have a sister; we’re very close. We shared a room our entire childhood and were completely at war the entire time, but grew into very close friends. I did not realize the book was going to be about the characters going off and connecting with their own siblings, but when it did it gained a lot of momentum, because it was something that I started realizing I could write a lot about and had a lot of feelings about. I know this isn’t everyone’s experience, but it’s been cool having this example of someone you haven’t chosen who is just automatically there and will always be there, regardless of how much shit you have between you. It’s an interesting way of thinking about indispensability.

It seems like a type of relationship that can be so close but also so fraught. It’s interesting to see Ray rebuilding with her sibling whereas, with Bron, that relationship just isn’t quite there yet. But you do feel that there’s potential for it.

I hope that the book ends in a place where there’s lots of potential for all the different kinds of relationships. I think [Ray and Bron] would be friends, and I think there’s an effort to try and project that a little bit in the conversation they have around whether Bron can still be an auntie at the end. Ray needs some time, but I’d be surprised if not.

Bron and Gracie are the most ambiguous. They end on a bit of a sour point, but I just can’t see any of those relationships actually falling flat at that point. I want to show relationships in which people are having a messy time and just continuously trying, and picking up again, and trying it from a different angle. And not having a rosy time about it, the entire time. [Laughs.] I really appreciate effort.

It’s hard when, for Ray and Bron, there is that concerted effort at communication, but it doesn’t work. Which is true to life: it doesn’t always work. Do you agree with Ray when she says that there’s “no amount of storytelling or sharing or talking that would close the gap”?

I don’t know if it’s as simple as there being a gap to close. It’s maybe rethinking the gap. One of the things that I wanted to show in their relationship is this idea that Ray is a bit scared of Bron, or fears the things that might not serve the relationship. And then those things bubble over anyway. If there’s going to be any kind of sustainability, those short-term efforts to create compatibility just won’t work. You can’t cut it to make it fit. Maybe the gap needs to exist.

Bron in particular really struggles with being not just looked at, but seen. Why is that kind of recognition so important to her?

It’s painful and alienating to be just looked at. I don’t think people can get much done, in terms of thriving, from that place. But I also think that, if someone has not felt seen, it becomes hard to know how to get seen. If someone has always been othered, it becomes hard to create relationships where you can trust that you can open yourself up enough to feel something. That’s definitely and obviously a very real thing for trans folks, and there’s also the thing of growing up thinking you don’t exist. That is a very difficult way to become an adult. Being seen is just being in connection [in a way] that is real and whole, and I don’t think anyone has an easy time with that part, regardless of who they are. But it’s essential for survival. I think she’s just an example of how difficult it can be for someone.

Final question: Why have the peach as a metaphor? Is it just go-to queer symbolism in a post-Call Me by Your Name world?

I forgot about the fucking of the peach! Oh god, it probably is, yeah. Like most people, I just love a good metaphor. I don’t like binaries or categories but use them just as much as everybody else to play with ideas. We all seem to love horoscopes even though they are definitive in ways that are not particularly helpful.

[Laughs] Agreed.

I still love talking about them.

I’m the most Taurus.

I’m a Taurus moon!

I’m a Scorpio moon, I feel a lot of feelings inside.

I love that for you. One of the metaphors that I was enjoying talking about with friends while I was writing—as a way of nerding out about feelings and modes of connection—was this idea of the peach and the walnut as different ways of doing vulnerability. The idea that someone has this Cancer crab outer shell where they’re really spiky and impenetrable, but then they’re just this fucking ocean of soft feelings and vulnerability inside once someone has proven themselves to be trustworthy. And then there’s the peach person whose defences and coping mechanisms look like being really agreeable and friendly and soft on the outside, but then if someone actually starts connecting with them, they realize that there’s quite an inner wall. I think it can actually be kind of disastrous when two people connect without realizing that they’re different in that way. And so they’re bringing preconceived ideas around trust into that way of connecting. It can be hazardous.

Well, I’m down for that being the next astrology, or the next love languages.

[Laughs] The peach and the walnut! I’m definitely a peach.