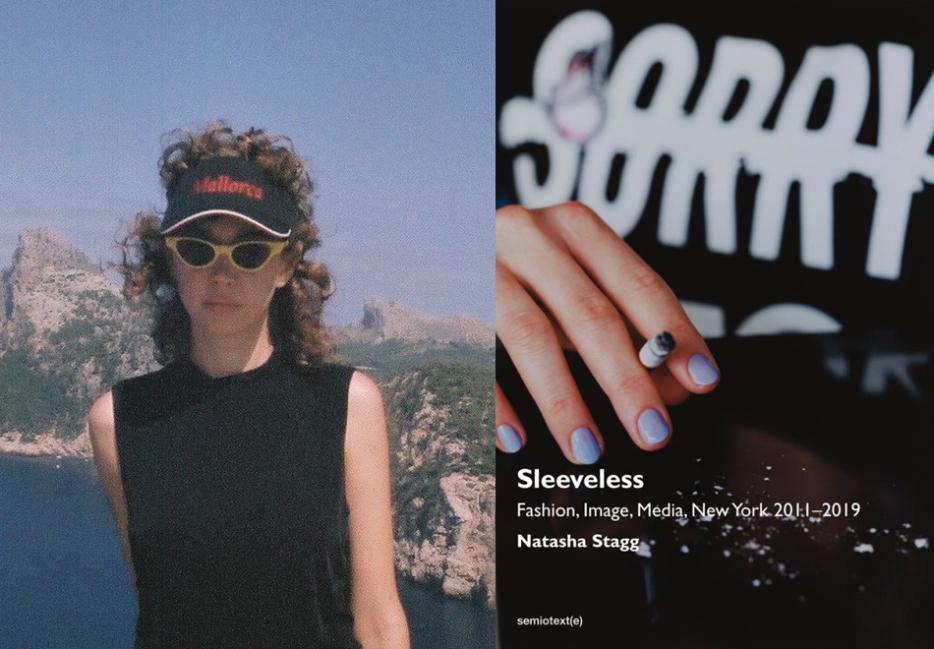

In her book of critical essays on artists Forty-One False Starts, Janet Malcolm writes, “There are places in New York where the city’s anarchic, accommodating spirit, its fundamental irrepressible aimlessness and heedlessness have found especially firm footholds.” Opening a copy of Natasha Stagg’s Sleeveless (Semiotext(e)) is like entering one of those footholds, be it the red glow of China Chalet at 3 a.m., a corporate warehouse party where everyone is beautiful and no one talks to each other, or a downtown coffee shop buzzing with nervous, striving energy where the person at the next table happens to be Coco Gordon Moore.

Sleeveless covers the glittering void of 2010s New York, which Stagg chronicled first as a contributor for the underground art magazine DIS, then as a senior editor at fashion glossy V, and now from the aerial view of a copywriter shilling for the brands she used to cover. It’s an endless parade of free cocktails and vacuous conversations where Stagg serves as both participant and observer; a bit like Andy Warhol’s diaries if they were written by a millennial, populated by shiny happy people until an unflattering zoom reveals the rot festering inside. Stagg writes, “I love expensive things but I hate being around people who can afford them,” which may well serve as a metaphor for the entire book.

Stagg’s New York is nearly fifty years past the decadent heyday chronicled in Patti Smith’s Just Kids, David Wojnarowicz’s Close to Knives and fictional texts like Slaves of New York and Bright Lights, Big City. But instead of complaining about missing out on all the good times, Stagg ventures into the fraught territory of chronicling her own era, which is still ripe with the turmoil, angst, and ennui that make New York both unbearable and the greatest place in the world.

Isabel Slone: It occurred to me while reading Sleeveless that you’ve managed to capture and preserve a specific era of New York in amber, specifically the intertwined fashion and literary scenes of the 2010s. Did you set out to write a quintessential New York book?

Natasha Stagg: I had been trying to write another novel—I wrote a novel a few years ago—and was pretty stuck trying to write another one for a bunch of different reasons, then realized the whole world is too bizarre to write something fictional right now. Most of this work was not done in preparation for a book, but on assignment. The intention of editing all of these stories together was to capture a moment and to kind of challenge myself to not be afraid of doing that. I think a lot of writers are afraid of sounding dated when they just write about one particular time period.

I guess I was just thinking, "If I’m not writing a novel, what do I have? What am I doing? Am I going to be able to write something ever again?" Then I try to motivate myself by looking at things I wrote for some other reason. I have all these folders on my computer and looking through them, I realized there was enough for two books and all I had to do was figure out how to make them feel cohesive. I ended up just sending a big folder of work to Chris Kraus, she’s my editor, and she was like, "Basically don’t change the format here, this is just chapters."

When you were going through the folders on your computer, was there a reason for selecting the pieces you chose to single out and rework for the book?

I started seeing a theme of articles that were questioning personal image, personal brands and the way one sees oneself in this era, which is shifting a lot every day. Whatever I wrote ten years ago, I would probably write differently now, but it’s interesting to see what I was imagining would happen in the future back then. Most of the articles I chose weren’t about a typical celebrity. They’re about a person that is in a very precarious place in terms of their status and visibility. That added to this longer narrative I had in my mind of what is going on with the way people view themselves in this age, whatever you want to call it, and all the changes that have occurred in the past 10 years in terms of media.

The precariousness you mention also applies to the way the book is narrated; it often feels as if you’re this dual character, playing the role of participant and observer at the same time. I’m curious, how did you end up working in fashion in the first place?

When I moved to New York, the first job I got was at Beacon’s Closet. To me, it was the best job ever, because I met so many interesting people. It’s this unique place that attracts really interesting people like stylists, fashion journalists, drag queens and all these other kinds of performers. Before I moved to New York, I was writing a column for DIS magazine, so I met a lot of people through them, and Beacon’s Closet, and just living here. Very quickly, within a year of living here, I got the job at V magazine. I worked with Patrik Sandberg who has become a very close friend of mine over the years. After that, I took all these other writing jobs and now I work for a few different brands through a design firm and do my own freelance stuff writing press copy and articles for magazines whenever I want to.

In the book, you refer to fashion as “the most insecure of any art form,” and I’d like to discuss that statement specifically in regards to fashion writing. Often I’ll see someone on Twitter asking for a recommendation for "good fashion writing," as if it’s this excruciatingly rare thing that’s impossible to find. It almost seems like people choose to actively ignore all of the good fashion writing getting published in order to preserve the idea that its difficult to be a rigorous thinker on the subject of fashion. What do you think about that?

This happened to me yesterday. I was at a talk and somebody asked for a recommendation for good fashion writing, and the panel’s response was to seek out participants in call-out culture, like Diet Prada. You know, the kind of Instagram accounts responding to culture and saying, "This is what you should know about this collection that the critics won’t tell you because they’re getting paid and I’m not." I think there is really good critical fashion writing out there and what’s stopping people from finding it is they’re looking at fashion magazines for it. Those magazines can’t afford to be critical of their advertisers.

What is unique about fashion is that there’s this exclusive component. With art writing, anybody can go to a gallery opening, you don’t have to be on the list. You do have to become a networker to get exclusives on artists, it’s the same with any type of journalism, but there isn’t this exalted status of fashion journalist where you get to show up and borrow clothes and be in this inner circle. It all looks very rich and exciting and they basically become a brand ambassador when they’re invited to be a critic at the same time. There is something unique about fashion criticism: it kills itself eventually. Anybody who is looking to become a good fashion journalist is easily brought into the fold, which means they can’t be a good fashion journalist because they’re too biased.

One of the main themes in the book is jealousy: romantic, professional and otherwise. You write, “Jealousy is the most poisonous emotion and admiration is always laced with it.” What drives you to explore jealousy and get cozy with that sick feeling?

I experience it a lot. People lie to themselves if they say they don’t. Most of the time, if they’re participating in social media, they’re participating in an endless trap of jealousy. That’s the reason why all these apps are so addictive, probably; this sick jealousy that we all have needs to feed itself. Then it drives us to project our own actions just to make sure everyone knows that we’re not jealous or doing something people could also be jealous of. Everyone is super jealous of everybody’s lives no matter who they are. It’s the way that jealousy has shaped the media I find interesting. I’ve always been obsessed with celebrities throughout my life, but then we all discovered that you could also be obsessed with a non-celebrity, and that is the idea behind influencers. Technically everybody is an influencer and therefore everybody can be influenced.

That you can actually put numbers on the level of jealousy we experience daily is so interesting to me. Imagine living 100 years ago, when there were no numbers behind any of these emotions and now its quantifiable. Well, except that it’s not. All those numbers are phony in their own way. But I think the impulse to make everything into a chart and a graph is a fascinating one.

Your novel Surveys is essentially written about an influencer before the term became ubiquitous. Now people are having conversations about whether or not the influencer bubble is going to burst. Do you have a perspective on that?

My instinct tells me that it will burst. In its current form, the influencer marketing strategy will become defunct in some way. Like all advertising, people get wise to a certain strategy and then they don’t trust it, so advertisers need to find a new way to capture their attention or their trust. I don’t think that will ever end. There’s no way advertisers will stop being super creative in ways to manipulate their audience into thinking someone they know or admire uses a product. At least I notice that everything getting sent to my feed is more and more appropriate. I think, "Oh that is an interesting new brand, and it’s sustainable and I can buy it right now." The algorithm that produces the content is directly doing its job. I don’t see someone’s face and think, "Because she uses it, I should use it," but it’s the same kind of shit. Somebody has found out what I look at, suggested that if I look at that, then I should look at this. It’s not that different. I’m still being fed a lifestyle that should influence me.

I really liked when you wrote, "I could always sway people in a conversation by using the phrase 'out of touch.’” Who do you think is out of touch right now?

Sometimes I say that about myself, you know? "Well, don’t ask me, I’m out of touch." It’s just this perfect way of getting out of something. Most of the time when I say that in meetings it’s not even accurate, I just don’t want to keep talking about a certain person. It’s so bizarre to me. Remember a few years ago, when every single fashion brand wanted A$AP Rocky to be their mascot? In hindsight, that makes so much sense. They wanted to check a lot of boxes; he was very safe in a lot of ways but also dangerous in the right ways and interested in fashion, whatever.

I feel like that person for right now is Billie Eilish.

Oh totally. She checks so many boxes of what a quintessential person of today should look like and behave like. Whenever this happens, I get so sick of hearing their name, it makes me feel their time is almost up. So I have to say, "I think that’s kind of out of touch," or, "I think that’s kind of over." But nobody listens to me anyways. I’m not like some bigshot in any advertising meetings ever, I’m just kind of there.