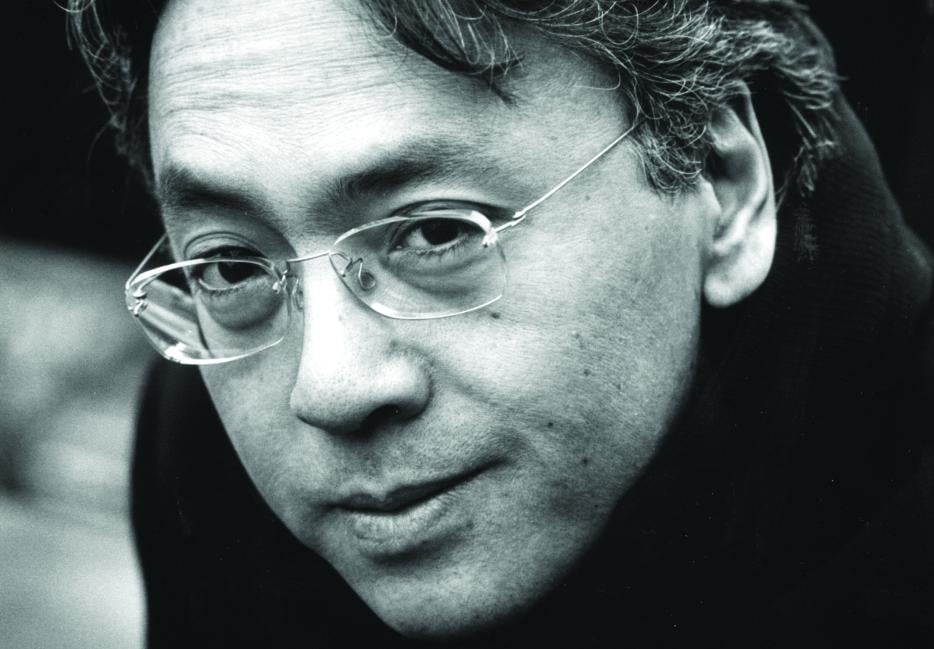

Being a fan of Kazuo Ishiguro is as much an act of faith as an expression of taste. We the devout can’t imagine what we’ll get when we take an unread volume down from the shelf, or click to commit to a pre-order. I’ve read nearly everything he’s published—all the novels and stories together run to only a couple thousand pages—but I’ve never used the phrase, “Ishiguro-esque,” and I’m not sure what I’d mean by that if I did. I doubt BuzzFeed will ever publish, “21 Ways To Tell If You’re In A Kazuo Ishiguro Novel.”

A few weeks ago I was listening to a podcast on which Ishiguro was the guest. The premise was a public book club. In the introduction, the host referred to him as “the Japanese novelist Kazuo Ishiguro.” It’s accurate as far as country of origin goes, but it still inspired me to bellow at my little Bluetooth speaker, “He’s lived in Britain for ninety percent of his life and won the Man Booker Prize for a novel about an emotionally stunted butler, you provincial Thatcherite turd! What does he have to do to be called a British novelist?”

But as I spat it out, the phrase “British novelist” didn’t feel right, either. (And obviously I instantly regretted “provincial Thatcherite turd.”) Was “British” any less lazy a word to use to describe him as a writer than “Japanese?” British like who? Nick Hornby? Hilary Mantel? Zadie Smith? Julian Barnes? I was suddenly sympathetic to the podcast host and imagined her experiencing a similar struggle. The eventual mistake wasn’t using the word “Japanese,” but giving in to the impulse to modify the word “novelist” at all.

Marketers have arrived at a different scheme for categorizing the indefinable. Current covers for all of Ishiguro’s books (including The Buried Giant, published this month) bear a variation on this blurb: “By the author of The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go.” These two novels were adapted into successful movies and, owing to the box office’s unparalleled ability to promote books on a massive scale, they’re the ones you’re most likely to have already read or at least heard of. You can’t fault the marketing department for beating back obscurity by playing the short odds. But as enjoyable as they both are, these are the wrong books to start with if you want to make sense of anything else Ishiguro’s written.

His Buried Giant

The first Ishiguro novel you read should be The Unconsoled. At more than 500 pages, it’s nearly as long as his first three novels combined, which is kind of the point. It was published in 1995, six years after Ishiguro won the Booker Prize for The Remains of the Day and two years after that book’s movie adaptation pulled over half a dozen Oscar nominations: expectations couldn’t have been higher. The world awaited a repeat, another E. M. Forster-esque story of regret, possibly set in post-war Japan, as his first two novels were. What they got instead was an endless, anxious dream about a touring musician. It’s aged well and, 20 years later, is widely accepted in critical circles as a kind of masterpiece, but according to Goodreads it’s still his least-read and least popular book.

The plot is simple. Ryder, a renowned concert pianist, is visiting a European city where he’s scheduled to give an eagerly anticipated performance. But in the days leading up to the concert, he experiences dozens of semi-absurd distractions and tenuous obligations. Time doesn’t seem to be working the way it’s supposed to, and he makes foolhardy decisions like getting into a car to go across town to meet the mayor’s mother even though he should already be at the venue warming up. By then, it turns out, nobody’s coming anyway—the tickets were marked with the wrong day. That last part might not actually happen in The Unconsoled quite as I describe it (or at all); it’s probably a dream I had during the week I spent reading it. That’s one of the things I love about this book: there’s no truer representation of the anxiety and capricious logic of dreams, and it’s stayed with me for years as a not-quite-remembered nightmare.

Where reading normally requires a fairly robust memory as you carry details (with the author’s help) and reflect on them at different points in the narrative, memory isn’t that important in The Unconsoled. Countless contemporary novels are described as “lyrical” and “musical,” but the experience of reading The Unconsoled really does resemble what it’s like to listen to music. Enjoyment of the prose occurs in the moment with no obligation to remember what happened before: it’s sufficient to engage with the waves of tension and release during a single sitting.

“These last months. I saw the caterpillars, but I went on, I went on, I made myself ready. It will be for nothing if you don’t come back.”

On the page where this conversation takes place, it makes perfect sense. I have no idea what happens to the caterpillars and it doesn’t matter. You probably don’t want to spend a lifetime reading books like this, but you’d be missing a reading experience unlike any other if you skipped this one.

The Unconsoled was the first Ishiguro novel I read. While this wasn’t a deliberate path (hooray for the remainder bin!), it’s been key to enjoying his other work. After following Ryder through his surreal week, I was primed to see everything by Ishiguro through a lens of anxiety, obligation, and an obsession with memory or, to be precise, despairing forgetfulness. These themes are everywhere in Ishiguro’s work, but only two of Ishiguro’s books put them in the foreground, and one of them is The Unconsoled.

Never Letting Go

To get a handle on why everyone’s so worked up over Ishiguro’s new book, the right one to read next is Never Let Me Go. It’s really, really hard to talk about this novel without giving away the fun of it. It reminds me of some of Margaret Atwood’s later work, and there, I’ve already said too much. But I will also say this: it’s as close to a bona fide page-turner as Ishiguro’s ever written, even if what keeps you turning the pages is the desire to find out exactly what these young men and women aren’t quite saying about their career plans.

Which brings us to the other of Ishiguro’s “blurb books.”

Probably because of the film adaptation (or just the movie tie-in paperback edition), many readers seem to come at The Remains of the Day expecting a work of delicate, lace-handkerchief-gripping emotion. And that’s a shame, because taken on its own terms it’s a brilliant, tightly controlled comic novel with a deeply misguided narrator, not unlike Ignatius Reilly of John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces. In The Remains of the Day, the butler Stevens philosophizes endlessly on his high-minded personal code of conduct, and yet his most athletic moral and intellectual contortions can’t hide from the reader the witlessness and anti-Semitism of his employer, Lord Darlington. Meanwhile, despite his much-professed humility as one devoted to a life in service, Stevens is all too happy to be mistaken for a gentleman by townsfolk when he’s out for a drive in his employer’s car. Yes, it’s also a story of unspoken love, between Stevens and his colleague Miss Kenton, but he goes to comical lengths to maintain his emotional distance.

Catching Up

The momentum of Ishiguro’s two most accessible, blurb-worthy books is exactly what you’ll need to propel you into 2015’s The Buried Giant. The New Republic called it “his riskiest yet,” and for good reason. Ishiguro appears to be setting a pattern of meeting elevated expectations (Never Let Me Go, released a decade ago, precedes his latest) with a challenging, peculiar book, just as he did when The Unconsoled followed The Remains of the Day. If there’s a critic alive who expected that we’d ever see a novel by Kazuo Ishiguro featuring pixies, ogres, Merlin, Sir Gawain, sword fights, or a dragon, they have yet to speak up in a public forum.

The Buried Giant centres on an elderly couple in 6th century Britain, Axl and Beatrice. As a fog descends on the land, inducing a kind of forgetfulness, Axl and Beatrice pick at memories, their own and each other’s, trying to piece together the details of an offence committed against them in their village (something about the confiscation of a candle) and on what terms their son left years ago, as well as how they might be received if they were to go to stay with him for a while.

In the opening chapters of The Buried Giant, I thought Ishiguro had mashed up The Unconsoled and The Canterbury Tales. But as The Buried Giant explores the conflict of Anglo-Saxon Britain alongside Arthurian legend, it starts to feel like an allegory for the west’s military presence in the Middle East, or the tensions in multiculturalism, or one of the 20th century’s genocides. Or, perhaps, something else I haven’t pieced together yet. I finished the book over a week ago but there’s a part of me still reading it, still journeying through the fog with Axl and Beatrice.

Whether The Buried Giant will find a place in Ishiguro’s cover blurbs before we see another book from him is hard to say (and who knows if the likelihood grows over time?) but if there’s one thing you learn as an Ishiguro fan, it’s that there are good things coming to those of us prepared to embrace the unexpected.