In the 1986 John Hughes-penned film Pretty in Pink, Molly Ringwald plays Andie Walsh, a quick-witted, externally tough, yet entirely sympathetic fashion-savvy teenager with a preference for New Wave. In the way of teenage movie clichés, Andie is from the “wrong side of the tracks.” She lives with her unemployed, unmotivated, depressed father who can’t stop comparing Andie to his wife, who ditched the family before Andie hit her teenage years. Andie must take up the role of head of the household. She looks for job opportunities for her father and encourages him to finally toss the bathrobe for actual clothes. Yet Andie’s father is stubborn, comforted by the past and terrified of a future without his wife. Andie loves her father but as the movie progresses, she inches closer to her breaking point. This culminates in an emotional scene in which Andie directly confronts him, shouting, in reference to her mother, “SHE’S NEVER COMING BACK.”

Despite how much I sometimes longed for my life to resemble a John Hughes movie, the reality of my teenaged existence was very different from that of those All-American white kids in the suburbs. But Pretty in Pink is the exception. It’s one of the few beloved films from my teenage years that incorporated a narrative about the pains of a dysfunctional father-daughter relationship. Andie’s father shows his love for his daughter through unexpected acts of kindness, such as buying her a pink prom dress foraged from the thrift store. But his short bursts of thoughtfulness are outweighed by his ability to make Andie feel guilty, and his toxic, defeatist attitude.

*

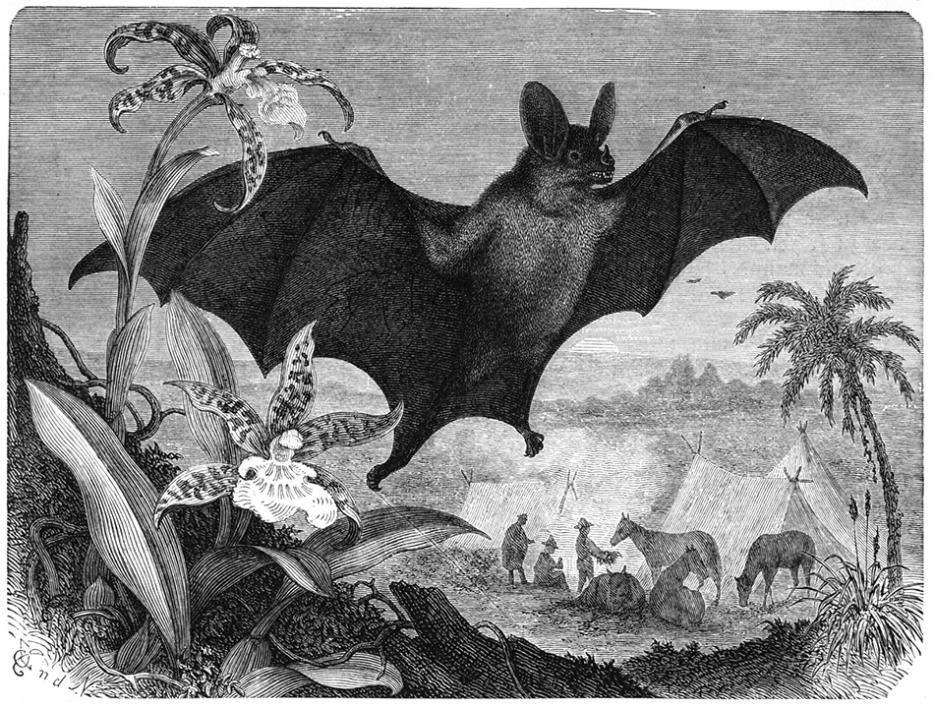

My dad has always been a horror movie fan. He says that he doesn’t get scared easily. The only two films to really have stunned and disturbed him were The Exorcist and Clive Barker’s Hellraiser. My dad, who hasn’t stepped foot into a church for mass in years, will be the first to tell you that the Devil is real and he suspects that he’s had a guardian angel or some kind of other worldly entity who saved him in near-death experiences. His faith is absolute, yet it does not extend to faith in treatment for mental health. The doctors and the prescriptions and the therapy are less real than his personalized Christianity, less real than the werewolves and masked men and vampires that populate his extensive movie collection.

One sunny weekend afternoon, he and I watched It, based on the Stephen King novel. Having never seen the movie, I was surprised to find Pennywise intimidatingly ghoulish. I’ve never been afraid of clowns, but Tim Curry’s performance effectively turns a childhood banality into a teeth-gnashing monster. At one point, I jumped, and my father laughed at me, a laugh so wide I saw a flash of silver from the fillings in his back teeth.

“These things don’t scare me. It’s not real,” he said.

*

Growing up, my dad made it a point to be my ally, the one who was skittish towards physical punishment. He was “always in my corner.” I wasn’t just his first-born and his only daughter, but his buddy. My dad was always telling me that I could do anything in the world, like I was the last princess in an important dynasty, kept away in squalor. My dad took me to Britney Spears concerts and to WWF matches when Dwayne Johnson was still only known as The Rock. I got him into reading again, and he showed me the brilliance of Wes Craven and Quentin Tarantino movies. I was a sidekick and a daughter and a jewel and as I got older, the pressure of each role exponentially increased.

A parent, with their innate authority, demands you look back.

When I was twenty-one, my parents’ marriage ended. Suddenly, I was my dad’s confidante, therapist, and liaison. Our conversations somehow always circled back to his frustrations about the divorce. We could be talking about a new movie and have it lead to an impassioned monologue about how my mother didn’t like to go out as a couple. Once, my mother had some extra food and decided to give the leftovers to my dad. Later, when I went to retrieve the Tupperware, he greeted me with a grim expression. “You know that food your mother made? I think she put something in it. I got real sick after I ate it.”

I felt like a double agent around him. I didn’t want to discourage my dad from his rants, because I thought he was supposed to share things like that with me. I tried to establish boundaries for us. When he ventured into the territory of badmouthing my mom and their marriage, I would insist he stop. Sometimes he listened. Sometimes he kept going, making excuses for the bile. If he couldn’t talk to his daughter, he said, whom was he supposed to talk to?

*

Dr. Al Bernstein, a clinical psychologist and author of Emotional Vampires: Dealing with People Who Drain You Dry, says that emotional vampires “look better than regular people... You like them, you trust them, you expect more from them than you do from other people. You expect more; you get less, and in the end you get taken." Writer Bethany Lamont, founder of the literary journal Doll Hospital, believes that it’s hard to identify emotional vampires. I should know how to pinpoint emotional vampires, though: some experts watching from armchairs would conclude that the first one I encountered was my dad.

When people use the term “daddy issues,” the implication is that the girl or woman in question is the one who bears the bulk of the responsibility for that relationship—that she is unstable and wild, that the Madwoman in the Attic lurks behind the facade and appears when you shut off the lights. Dealing with an emotionally vampiric parent provokes the same sort of low self-worth. Although she does not use the specific term, Dr. Karyl McBride, author of Will I Ever Be Good Enough: Healing the Daughters of Narcissistic Mothers, describes narcissism in a way that echoes it: “Many children of narcissists are put in what we call a ‘parentified child’ position where they are taking care of the parent,” she says. “This is not the job of the child and many are asked to do this before they have grown and matured themselves. It is an impossible task and causes an internalized message of ‘I will never be good enough,’ because they are too young to do it or do it well.”

"It’s a scary feeling to suddenly realise the people you surround yourself with are making you miserable."

My relationship with my dad rippled out to other aspects of my life. I fought more with my then-boyfriend, who didn’t understand why I couldn’t just talk to my father about what was bothering me. He didn’t believe that no matter how bluntly I told my dad that I didn’t want to talk about my mom, he would conveniently forget ten minutes later. It was difficult to do what my father was silently asking me to do: turn my back on my mother. I was stuck in the middle. No one had asked me to take sides, but it was obvious that I needed to choose.

According to Dr. McBride, setting up boundaries is “a process of accepting, grieving, psychologically gaining individuation, rebuilding their own sense of self.” I grieved for the dad who didn’t exist anymore, swallowed by the man he became post-divorce. Much to his dismay and confusion, I moved out and moved in with my mom. If I couldn’t create a mental barrier, then the next best thing was a physical one. The effort required to deal with my dad was backbreaking. As Dr. Bernstein says, “sometimes it’s better to run away.”

*

In an interview with the Sunday Times Magazine, the singer FKA twigs said, “If someone makes me feel weird about myself, then I just stop talking to them. I walk away all the time.” We’d all do well to follow this advice, but as evidenced by the interviewer’s shocked reaction to twigs’s statement, letting go of someone toxic requires more strength than you might believe. Some people pour their poison into your marrow until you no longer recognize it as fatal to your health.

Friendships with emotional vampires can be easier to escape than family bonds. The debt is not as morally daunting, the blood not as thick. A parent, with their innate authority, demands you look back. But the pain of self-preservation is necessary. Remaining faithful to an emotional vampire not only harms the host, but it sustains the vampire’s negativity. Learning how to free oneself can save two lives. Lamont acknowledges that it’s “a scary feeling to suddenly realise the people you surround yourself with are making you miserable.” Mindfulness is the ultimate weapon. The first step in battling these emotional vampires is to be aware of their sorcery.

When my brother turned 18, my dad viewed it as his ticket to get the hell out of dodge. He’d never been taken by his Connecticut hometown. He was forever yearning for a new place and new strangers, people who left him alone and stayed on their side of the fence. In a way, he blames his hometown for his unrealized dreams and missed opportunities, the tiny doors that open during youth and steadily shut as time passes. He left.

It seems that the absence of my father has strengthened our relationship, or at least begun to repair the damage, like nerves in the brain finding an alternative way to fire. I will always love him because he’s my father, but I know that in order to maintain a healthy relationship with him, I need breathing room. I am a better daughter from afar.