Birds are having a real moment right now—bird-identification apps, newly converted birders, repurposed Instagram accounts. And even if it’s brought on by all that birdsong we can finally hear, this moment is well overdue. But it’s also terribly fragile.

In the last three decades, over a third of North America’s birds have vanished—that’s three billion birds. In India, where I live, the first nationwide study found that 80 percent of observed species were declining. In the UK, where I used to live, nearly a quarter of bird populations face extinction or steep decline.

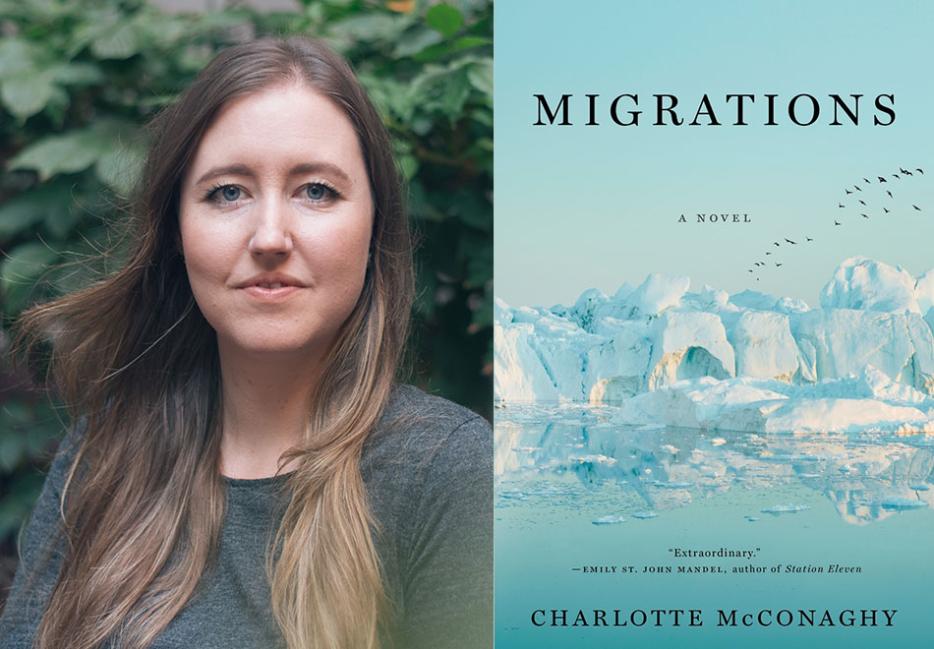

In Migrations (Flatiron Books), the moment of the birds has passed. Along with that of the bears, deer, wolves, fish, bees, and trees. Set against a landscape of immense loss, Charlotte McConaghy’s evocative new novel charts the story of Franny, who attempts to follow the last flock of Arctic terns as they fly from one end of the earth to the other.

Together with the wary crew of a fishing boat, Franny finds herself immersed in terrain that’s as unstable and precarious as her interior world. As McConaghy writes: “There is hardly anything wild left, and this is a fate we are, all of us, intimately aware of.” And if we have any hope of salvaging the natural world, Migrations suggests that we may have to uncover our own wildness first.

Richa Kaul Padte: There’s a moment when your narrator Franny is explaining the immense journey of the Arctic terns—from the North to the South Pole and back again, all in a single year. She says, “I think of the courage of this and I could cry.” What, in turn, is the sort of courage required by humans to face the world of Migrations—one in which practically all the animals, birds, and insects that once populated the earth have died?

Charlotte McConaghy: Great question! I like to think of the courage of the terns’ journey as a metaphor for the courage that Franny—and all humans—need in facing the looming animal extinctions. It’s so hard not to be overwhelmed by the magnitude of this crisis, and to feel hopeless or apathetic in the face of it. It seems too big for any one of us to be able to stop, but I wanted the book to be a battle cry of sorts. To say no, we can make a difference, we can take up this fight, and in fact we have an individual responsibility to do so. Franny’s journey (without giving too much away) is one of hopelessness to a reclaiming of hope, and it requires a lot of courage from her to reach that point; this is what we will need in order to reclaim our own hope—and not only hope, but the energy required to take on a journey as vast as the flight of the terns.

Do you think this hope and energy partly comes from noticing—and in the case of Migrations, remembering—the remaining wildness in the world? There’s this moment when Franny sees the terns and thinks: “Easy to forget how many there once were, how common they seemed. Easy to forget how lovely they are.” Is paying attention a way to energize ourselves in the face of despair?

Absolutely! The more we notice these beautiful creatures the more we will value them. And we don’t have to look far. Go for a walk and really look at the trees you see, study their leaves and try to spot the birds that hide among them. Find some water and sit beside it, it won’t take long for water birds to come and sit on its surface or dive below for fish. Sit quietly and listen to the sound of the wind. Spot the little bugs that find their way into your home and instead of squishing them, help them on their way. Everything has an important role to play. Take pleasure from all of these living creatures; every one of them is a wonder. We have the capacity to take such joy from the natural world, and I think you’re absolutely right that this helps to stave off the despair we feel when we think it’s all gone. It hasn’t gone yet. There’s still time to save it.

Woven through your book is a “nameless sadness, the fading away of the birds...of the animals.” Franny remarks: “How lonely it will be here, when it’s just us.” This reminds me of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s concept of “species loneliness”—a “deep, unnamed sadness” arising from human estrangement with other species. Both Franny and Kimmerer describe this loss as unnamed; what, if anything, shifts when we try to name it?

Perhaps the attempt to name it is what separates us from other species—the need for language to define and understand how we feel and what we yearn for. For animals there is only instinct. One of the things I wanted Franny to be, while thoughtful and contemplative, was more instinctive than most people, wilder, maybe, or more in touch with her wildness. This allows her to connect more deeply with the natural world, but also means she feels the loss of it keenly. I think we all must strive to connect more deeply with the world if we have any wish to salvage it and perhaps lessen some of that unnamed sadness. Whether we have the ability to identify it or not, it’s something that lives in us as deeply as instinct does, and maybe it’s a sign of our creatureliness, and hints that reconnection has the potential to nourish us all.

Oh, now that makes me wonder if it’s actually reductive to try and name this sadness! In the sense that maybe our constant need to name, classify and categorize everything—including our feelings—prevents us from forming the sorts of connections we need the most?

Yeah, I sometimes think that might be the case too. Overanalyzing and overthinking can feel like the occupation of a writer, which is why it was such a bone-deep relief to write about a character who doesn’t try to analyze what things mean, but instead tries to experience each moment, to really feel them. Franny is guided by emotion and I tried to let the writing process be that way. It’s a difficult thing when your job is to put language to emotion, because you must also know when language has its limitations and try to allow something deeper to shine through on the page.

Something you resist a lot in your text is the idea of human centrality—for example conservation efforts being focused on what benefits us the most. In Migrations, the work to save bees, butterflies, hummingbirds and other pollinators is well underway, while “no-hopers” are allowed to “fade into extinction.” But, as Franny asks, “wasn’t this attitude the problem to begin with?”

Yes, it really upsets me to think about the extinction crisis only in terms of how it will affect us humans. Sometimes it seems like the only argument that ever gets through to people is how damaged our food supply will be when there are no more pollinators to help us grow that food, or the thought of our homes being destroyed by flood or drought or fires or rising sea levels. It distresses me because we are not the only living creatures on this planet, nor the only ones with a right to safety. We are sharing this world; if anything, we are its caretakers. So I didn’t want this book to become a dystopian look at how our lives will be affected, I wanted it to be an existential exploration of how it will feel to be the only living things left here. I think it will be devastating. The thought of a world with only humans is a horrifying thought. The animals deserve to be here as much as we do, and not to serve any purpose, but to exist in their own right.

There is a growing tension in your book between climate activists and fishing communities, with the latter often positioned as enemies of the sea. Franny, for example, is shocked when the captain of the The Saghani—the only fishing vessel that agrees to take her aboard—releases a large catch to free a sea turtle caught in its net. I think the only thing that shocked me, though, was her shock. I’ve lived near fishing communities for a long time, and in fact just last month, fishermen in my home state of Goa, India, freed several Olive Ridley turtles.

Is there a truth in the terrible way some conservationists view fishing communities—a truth other than activists’ own privilege?

I think there is huge division between people on this subject, and unfortunately a lot of that stems from a lack of understanding of the other party. I’m a vegetarian, while my father is a beef and lamb farmer. There could be division between us but instead we have enough knowledge to understand each other. For Franny, in the world of Migrations, the seas have been even further ravaged than they are now (although we are headed that way swiftly), so she is aware only of a certain greed on the part of those who continue to fish despite the terrible state of the oceans. She just doesn’t understand why they carry on. For Ennis and his crew, there is even more desperation than there is for fishermen today—fish are so scarce they aren’t really able to make a living from it anymore, and this journey is a kind of last chance for them all, which is perhaps why Franny assumes that their need will outweigh their compassion. What she must learn is that there are complexities to us all; it is the systems that have been put in place that need to change.

I’m really interested in how knowledge operates in your book. Franny says of her scientist husband: “Niall has always wanted me to study the things I love, to learn them...in facts. But I’ve always been content to know them in other ways….the touch and feel of them.”

This makes me think of the biologist who refuses to believe that a flock of crows befriended Franny in her childhood. At the same time, we see that Franny’s instinctive love of birds and the sea is deepened by Niall’s research, too. Are these two ways of knowing contradictory, or can they compliment each other—even when what we are trying to know is wildness itself?

I think part of Franny’s journey is to understand that they can complement each other. There is certainly a sense of contradiction to her—she is hungry for knowledge of birds, sitting in on classes she’s not enrolled in just to learn more about them, while at the same time resisting the thought of making this learning official by committing to any kind of study. She’s frightened, I think, that the science of things might tarnish the magic she sees and feels in the wild. It’s her creatureliness that makes her disinterested in normal societal values—career ambition, wealth, etc.—but she comes to slowly understand that committing to learning about her passion doesn’t have to take the magic from it, and I think this is one of the gifts she gets from her husband. Just as he learns a kind of optimism from her about our potential impact on the natural world—and as we are all inevitably enriched in some way by our partners’ views.

“Creatureliness” is a word you’ve mentioned a couple times now, and it makes me think of Franny “reach[ing]…for poetry, for Mary Oliver and her wild geese and her animal bodies loving what they love.” What is creatureliness, and is it linked to how “we don’t always have to be a poison, a plague on the world…[how] we can nurture it too?”

Yes, I think so. I’ve always taken a great deal of inspiration from Mary Oliver’s poetry and her extraordinary ability to recognize how our connection to the natural world can feed and sustain us. I read recently that it’s our separation from nature that makes us harmful to it. That as we advanced technologically, we lost our ability to be harmonious with the rest of the world. I think there are those with a more natural ability to connect with animals and wild spaces, and maybe it’s because they are able to remember their own animal natures. The quiet we are capable of. Perhaps it’s only by reconnecting with our animal sides, or our “creatureliness,” that we will remember what it means not just to exist for our own sakes, but as part of a greater, vibrant, interconnected whole. Our place here can be nurturing and gentle, instead of destructive. This is a very important theme in the book and in Franny’s life. The realization that she, and all of us, can help instead of hinder, gives meaning and purpose to her life, and I hope readers can take a little of this from the novel.