It’s the afternoon of Thursday, March 12, 2020, and I’m in bed in my Brooklyn apartment. The bus releases air pressure just below my second story window several times an hour 24/7; after ten years in New York, the city of my dreams, this whoooosh is as soothing as crashing waves to me. I’m talking to Joseph Osmundson on speaker phone because I have tickets to the Tina Turner musical on Broadway tonight. And I want to go. And I’ve been doing a great job ignoring the reasons I shouldn’t. Inside me, an ethical seesaw is turning sideways, morphing into a nightmare carousel: Well, I reason, if we’re about to give things up for a while (a while being a few weeks, I reason), then let me have one last hurrah! I saved and budgeted and gave things up over the winter so I could afford these tickets. I work hard in this city, and my tradeoff is cultural entertainment. I deserve public fun in a room where professional bodies rhythmically inhale and exhale. So, I’m bargaining.

Joe, who in addition to being part of my queer nonfiction writing cohort is also a molecular biophysicist who specializes in viruses, says to me over the phone, “It’s time for us to care for the collective body.”

I met Joe in 2014 at a Los Angeles LAMBDA writing retreat (lambda, another variant of SARS-CoV-2). Our teacher was Randall Kenan, a gregarious man full of wisdom and sarcasm who had us write ekphrastic essays and called us his possums, and who would pass away early in the pandemic. Joe and I are almost the same age, two small town west coast weirdos lusting after the queer raunch and subcultural promise of the city, coming of age inside of an institutional metaphor of virus as punishment for hedonism. As adults, we have gorged ourselves on enough community and friendship and literature and movement action to understand that viruses are not vindictive. HIV doesn’t care about sodomy just as COVID-19 doesn’t care about elections or birthday parties or grandparents holding babies. Back home in New York, I got to know Joe the professor, the scientist, the podcaster, the Twitter scold, the cyclist who should really wear a helmet, and most of all, the writer. Joe is someone who organizes his life around being able to write, who just can’t not write, even after working, and biking, and drinking, and dancing.

Joe’s advice about the Tina Turner show was the first COVID moment that broke me: a moment at once global and highly personal, the moment when my floodgates of denial could no longer hold. I sobbed in bed, which was good, because Joe is famously a Pisces and it’s more than okay to cry to him; he might actually be annoyed if you didn’t cry. The intensity of emotion was about missing out on the fun I’d looked forward to, yes. What is grief if not disappointment about the way you expected things to go? But it was something else, too: it was the catharsis that comes from having people in your life who will tell you exactly what you need to hear so you can make your own decision to do the right thing.

Around 3 p.m., I accepted that I was going to give up my tickets. A few hours later, Broadway went dark. I wouldn’t have been able to go even if I’d chosen to ignore the gathering dread and take what I selfishly thought I deserved.

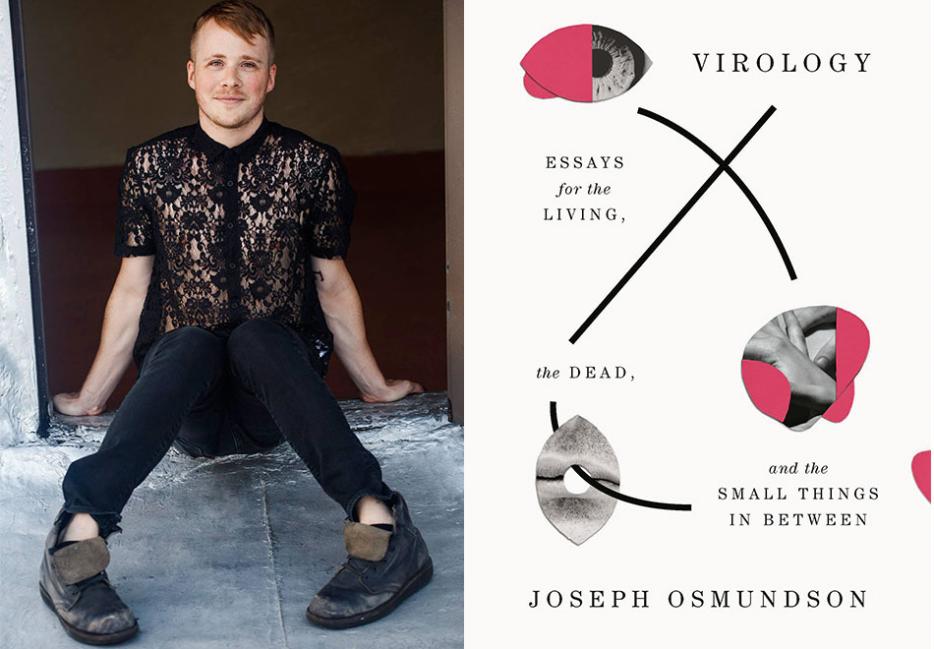

There’s a reason I haven’t written about this moment yet, or any of my pandemic moments, privately in a journal or publicly in print. And Joe puts his finger on why in his new book Virology (W. W. Norton), as he himself publishes journal entries from 2020: “We were making (too much) meaning in real time.” I found it tedious somehow to write from within the hyperobject. It’s only now, in summer 2022, as I can reflect on summer 2020 as history being archived, that I feel ready to read a book about the era we’re still living through.

The Broadway disappointment wasn’t the last time I would turn to Joe for virology therapy. I had been planning a move to California for a year. I had already uprooted myself, but didn’t know if it was safe or ethical to transplant considering how the world had changed seemingly overnight. I didn’t want to abandon New York. Then he told me: “This pandemic isn’t ending tomorrow or the next day. We have to live our lives.”

It sounds like the opposite of the “care for the collective body” guidance, but it wasn’t. This is what it means to queer advice. Queer advice isn’t about rules. It’s not a binary of hedonism versus selflessness, self-care versus political warfare. Queer advice is risk aware assessments and reprogramming, adaptation and design. So, I masked up, and moved across the country.

Two years and counting into the waves of emotion and variants and political geekshows of this pandemic, Joe has written the book of essays he was born to write. Reading it is like being at the club with Joe in the middle of the night, screaming over the bass about Sontag and quantum mechanics and poppers. It’s sensitive and rigorous, less a book about science than the humming mind of a scientist who happens to be a gay slut who reads too much. Joe’s prose reaches for both the grandest scale of humanity and the literal molecular levels of who we are. In it, he makes his queer advice canon, writing, “Quarantine is a social act, not a personal sacrifice.”

In April 2022 I got COVID for the first time. My feverish brain wanted to make rueful meaning of that moment in real time. But Joe and other activists have taught me to examine the ways we talk about viruses. To not treat it like the enemy, to not attribute agency to it. The meaning of that infection was that I got sick for a while, I stayed inside, and I survived. A month later, just as the advance review copy of his book arrived in the mailbox of my new apartment in Los Angeles, Joe got COVID, too. I interviewed him over text and shared docs while he recovered in his Brooklyn apartment with his partner, Devon, and their dog, MAX! We talked about science fiction metaphors, what PrEP has and hasn’t changed, and the fascism of wellness culture.

Tina Horn: At the risk (aware assessment) of acting in bad taste, I’m weirdly thrilled to be reading your virus book knowing your body is across the country literally infected with a virus right now. I’m a slut for a stunt, I guess. My brazenness is probably influenced by the fact that I, myself, got the novel coronavirus COVID-19 for the first time a month ago, and my cough is still rattling around, too.

Joe Osmundson: “Novel” coronavirus in that it likes conventional narrative structures and believes sometimes fiction is truer than journalism. Our relationships to viruses, whether we’re infected or not, are intimate. The virus can literally get inside us. This virus needs us. It gets stuck to us. It uses us. We initially let it inside and then try to push it out. It eventually will leave us, either to die in thin air (a true wish I have for all my exes) or to move on to another “host.” I wrote an essay in Virology about how we treat viruses as invading enemies in a war of sickness and health, but it’s just as easy to use metaphors of intimate relations, which can of course be either joyous or benign or deadly as well. SARS-CoV-2 is inside me right now, replicating, speaking to my immune system, which is activating itself to respond. There is of course a danger in this—a danger of losing my breath, or of never fully recovering. But there’s nothing more human than being infected with a virus.

Before I got sick, my partner had COVID, and we were isolating in our tiny New York one bedroom. When I tested positive and got to open the door to his room and check on him and hug him and bring him food, when I stopped worrying about infection but just had an infection, it was both frightening but also an immense relief. So little about viral infection is simple.

Many of us are in this newest, freshest hell: a triple vaxxxed, post-omicron surges, mask mandates lifting, everyone will probably get it and that’s fine or is it?! era. It feels disrespectful to those who have suffered and died—and those who still will and those who are grieving—to be excited about the literary/dramatic possibility of this conversation, you speaking about having COVID while we discuss your COVID book … but then again, your book is, among many things, about making meaning from tragedy. So, paint us a word picture, Dr. Joe. What is happening in the body and home of someone who is experiencing the symptoms of a virus he’s been educating the world about for two years of a generation-defining global pandemic? How are you and your queer family?

I have to admit that I am deeply saddened by this moment in our public life. It was our great hope, in 2020, that the fractures made more clear by COVID-19 would lead to change, and that we would do simple things to care for one another instead of racing back to a false normalcy that was already deadly. And here I am, May 2022, cases once again spiking, and our political leadership rolling back even simple things—mask mandates, vax checks—as more and more people get sick.

It is unavoidably true that our biomedical interventions—vaccines and drugs like Paxlovid—help many avoid the worst outcomes of this virus. It is also true that, as ever, biomedicine isn’t enough. We saw this with the HIV crisis: Who does biomedicine leave behind? Even with good HIV drugs for treatment and prevention, cases in the rural south—for example—are still rising yearly. We need more than drugs. My book is a case for mutual care for one another at all levels, including, not limited to, drugs.

Me? I’m a little sad about the fact that it seems like, if we want to live a faggot life in the world, going to bars or restaurants with friends, going to clubs or concerts, COVID-19 is something we are almost certainly going to face (and, frankly, even if we don’t). I said in 2020 that this virus could change what it means to be human; I think, in a way, it already has.

There’s someone in my life with whom I share, let’s say, some preferences for holistic healing modalities. A year ago, she told me to my face she would never let the government vaccinate her, and she doesn’t need to, because she “won’t give the virus permission to enter my body” (said with a little crossing of the arms over the chest). What I find most disturbing about this is how closely she and I think, in some ways, about health. And then the link between this kind of thinking about public health and the warped close-but-no-cigar ideology about trusting the government and the right to bodily autonomy. Especially in this fucking moment of federal reproductive injustice. Which laws do we want off our bodies?

I would LOVE to rant about the fascism/wellness overlap in the 2020s Venn diagram. This bizarro horseshoe theory overlap is centered on a belief in freedom as entirely individual, in responsibility for health as fully our own (as if everyone can eat organic and do yoga!) and a (healthy) skepticism of government perverted into what I call a “freedom” defined as the ability to harm others with our “personal” choices. When holistic wellness is centred only on the self, what is it but another non-scientific fascism? Another way to make oneself the perfect body. But, of course, no body can be perfect; all bodies will fall ill. This is just another attempt to look away from the world as it really is.

Right, and you explore “the freedom to harm others” in your essay “On Whiteness,” which is deeply relevant to both the Black Lives Matter civil uprising and to the commodification of self care. So this is something anti-establishment white queers like ourselves should be committed to interrogating.

The anti-vaccine “wellness” community turned a (often) healthy skepticism of science into raising a non-scientific epistemology (the vaccines are the virus) to the level of religion: the religion of one’s agency over one’s own body and health, which is obviously a lie.

“I can’t trust doctors (maybe fair), so I can heal my cancer with crystals.”

“I don’t believe the government actually wants to care for me and my health (fair), so I reject that government’s vaccine.”

I've been thinking a lot about where healthy skepticism bleeds into dogmatic reactionary thinking because, in part, of those on the left still hanging onto desperate idiot ideas about the USSR being … good? And Cuba today being … socialist? I’ve seen this around “leftist” vaccine skepticism and “leftist” tacit support of Russia in Ukraine because the “west” and “NATO” “provoked” this violent, deadly, and expansionist war.

All of this, I think, speaks to the abject failure of 20th century political frameworks to deal with the world as it is today. Humans on the margins, and most of us are in this context, are subject to an ongoing and life-threatening attack. We need a new politics. For me, this starts with close community and mutual care and will build itself up from there.

Close community and mutual care and dismantling white supremacy: this is how we build queer futures! So, what it is about this pandemic specifically that inspires magical thinking, from Q-ANON conspiracies to the myth that the police protect us from harm?

Facing the truth would require too much of us. It would require disruptions of the very frameworks of capitalism that let our lives hum along. Plagues force us to look closely at ourselves and one another when we have a whole late-capitalist society built on looking away from violence. I’m typing this on an iPhone made from mineral extraction and child labour. But in my day-to-day life I use my phone to look at porn more often than think about where this technology comes from.

We are desperate for a world in which COVID-19 doesn’t exist. I am desperate for that world. Remember going to The Eagle and kissing and dancing and not being afraid of getting a virus that could kill you? I do! And that freedom to be in public, to dance, to kiss, was precious and valuable and nothing to be ashamed of.

But this is the world we live in. It has COVID-19 in it. And rising fascism and climate disaster and geopolitical threats, and also BO and stubbed toes and hangovers and broken hearts. I think (white) Americans are uniquely bad at accepting that the world isn’t a Disney movie and that no one is coming to save us. I spent so long waiting for my own prince to arrive and *snap* make everything better. But we are the grown-ups now, Tina. It’s horrifying. We have to save ourselves, which we can’t do until we can see the world as it truly is.

Speaking of seeing the world as it truly is, I’m famously a fan of supernatural allegories for social problems. But in the early stages of the pandemic, I found the idea of entertainment as a response to what we were going through such a tedious prospect: the idea that basically all stories will be defined by this moment for the rest of my life. You talk in the book about some genre fiction metaphors: The Hot Zone and I Am Legend, the military response to disease, and viruses that make us zombies because of our hubris. Popular fiction is a place for us to work through our existential anxieties: nuclear fallout in the fifties, cold war paranoia in the seventies, and so on. Do you think the speculative fiction and big budget summer flicks of the 2020s will be more about plagues or more about social distancing? Or is the biggest horror that has emerged from this era the collision of the personal and political in the arena of public health?

My partner and I started watching the new Russian Doll last night, seven days into our COVID isolation. Idiot move. Too depressing. But it made me think about one thing, specifically, that’s been on my mind. That show is set specifically in the year 2022; it names the year. And yet it’s set in a world as if the panny never happened: no masks, no changes to life’s routines. We have had some incredible pandemic essays, we are now getting some essential pandemic books, but it seems to me that even art-minded mass entertainment like movies and TV is largely … looking away?

For movies, it kind of makes sense to me: they’re literally asking us to come back into movie theaters where we share air with strangers. Makes sense that they might not want to remind us of the respiratory pandemic we’re currently still in.

But I wonder about art (which can confront our most profound ills) and entertainment (which usually cannot) and the grey area between (which I believe does exist). Escaping our current and ongoing pandemic hell is important; we deserve pleasure and dumb superhero movies. I’m just not sure what type of art and entertainment will help us process, help us heal, and help us, as I say, not just face but rise to this, our one, but ongoing, precious moment in history.

I do believe it’s precious. Queer and trans people are under attack. The world is warming. The -isms are -ism-ing. Abortion is being rolled back, and abortion is awesome. We’re seeing a rise in moral and sexual panic. Fascism isn’t just rising here. This is our moment to dig in. What will we do with it?

I had the same thought watching Russian Doll! The reason it’s so striking is that, as an intergenerational trauma time travel story that is also very New York, it makes specific material of the exact date and space: the Astor Place Uptown 6 train platform in 2022. And in behind the scenes promotional photos, you see the crew on location in masks. So, what does it mean for us to have this parallel universe of stories where 2022 is not defined by N95s on people’s faces and littering the streets? When the time loop movie Palm Springs came out on Hulu in the summer of 2020 (when we were in dire need of some fun new content to stream from our couches) there was some commentary about how it became unexpectedly resonant: we all felt like we were living the same day over and over again. Do stories help us relive the past without being doomed to repeat it?

I love stories! But stories, like science, are a tool; they are not inherently good (or inherently evil). You have to consider what the story is, who’s telling it, and whether it reifies the status quo (which I would define as evil since the status quo is quite deadly) or challenges it (good, because this may help more people survive). I say this about science in my book, as well: so many view science as inherently good! “Follow the science!” they say. But this is, of course, not borne out by history, as I describe in great detail in the collection, particularly in the essay “On Whiteness,” which is about viruses and the deadly ways of whiteness.

But stories do have great potential, and they are necessary in our political work. One example that comes to front of mind is the FX TV show Reservation Dogs. Full disclosure is that my good friend Tommy Pico writes for the show, but it would come to mind regardless. It’s an all-Indigenous American sitcom, with everyone touching the show coming from Indigenous communities, from the showrunner to the grips and extras. The first season fried my narrative brain. It was otherworldly and spiritual but literal and grounded in this world. It looked directly at the manifestations of grief and loss but included the ridiculous and funny in addition to the expected sobs. It has a vision of policing—policing!—rooted in community and justice. It was funny. Like really funny. Nothing like it has ever been made before. That’s the kind of storytelling that makes new worlds possible.

Can you talk about the process of updating your 2016 Village Voice piece for the book? I’m interested in the craft of adaptation, but as a follow-up: does it feel different to have that piece archived in book form in the context of the other essays, as opposed to just living on the Voice’s webpage, especially since that legendary publication has since shuttered?

Oh! I am so glad you asked this! Adapting or updating published or older essays is such an essential part of collection making, and I’ve talked about it with some writing friends, but I don’t see it discussed much out in the world.

A few of the essays are updated for our current world, with the Voice article being one that needed a significant shift in thinking. I was writing that piece in late 2016, when PrEP for HIV was starting to shift the world profoundly; the book was written largely in 2020 and 2021, in the world shifted by PrEP and U=U (the notion that HIV positive people are the safest to fuck in terms of HIV risk) but now on a planet forever changed by SARS-CoV-2. What could that essay possibly say about this moment?

Well, I decided, a couple of things. One, it memorialized that moment in time, so I wanted to keep its perspective as one from that year. But a new lens of analysis was necessary: Biomedicine (namely PrEP and U=U) had profoundly and forever shifted the meaning of the HIV virus (at least for those with access to these interventions). So, the thinking became about how viruses shift over time, which added a layer to that essay.

The first essay from the book (“On Risk”) is also cobbled together from three pieces written and published in a hurry in early 2020. I tried my best to keep the urgency and feeling of that moment but to add —again—deeper thinking that wouldn’t have been possible in real time.

And then, in terms of the narrative of the book, I added something that was very difficult for me. The emotional weight of editing these old pieces, of looking back at the plot points of our own lives (so many of which are traumatic or horrible, as plot points often are) was heavy. In the essay, I don’t take PrEP, but manage my extra-relationship sex risk with condoms. Shortly after the essay came out, my partner at that time dumped me, and I had to start to make sex safer as a single person, my nightmare. So, I started PrEP myself. That last paragraph of that essay took months to write, not because the sentences are, like, so perfect and beautiful, but because I had to sit, and face the page, and write that moment—probably the hardest moment of my life— there for everyone to see.

I’m feeling a distinct tension right now between, on one hand, relief that I can do the joyful things I missed during two years of public health restriction (like kissing at The Eagle, or going to Broadway shows!), and on the other disappointment, fear, and judgment about other people’s increased risk-taking. For example, I went to see Bikini Kill at the Greek Theater a few weeks back: it’s an amphitheater, live music is important to my mental health, it feels like the right moment to reintroduce life-giving activities like this. On the way in, staff were checking vax cards. Great! But my friend had forgotten theirs and I had a moment of dread: oh no, is my friend going to be turned away from a show they bought tickets to? But the staff person waved them in with a little conspiratorial shhh. Now, I happen to know for a fact my friend is vaccinated. But if the staff of this venue were being lax in that moment, have vax cards become a TSA-like theater of inconvenience assuring us of the feeling of safety without creating actual conditions of safety? One more note: at the end of the show, a strange man approached my friends and me to ask us basic questions about the band, quickly launching into a rant about his right to be there even though he didn’t have his vax card. We’re all punks with good boundaries so we just got the fuck outta there, but it was a disturbing mystery moment: what is motivating people to infiltrate spaces of entertainment to attempt ideological persuasion?

This tension is the tension of living, I would say. For those of us who've been fags since the '80s, we know this tension: sex feels amazing! Oh, by the way, it can give you a deadly virus and there's no way to have sex without risk! HAVE FUN OUT THERE BABY GAYS!

I think the tension is a good thing: It means you give a shit. That pleasure is important to you (because you're a person and people should be able to feel pleasure), but that you aren't willing to sacrifice or harm others to get it. We all want COVID not to be a thing, but it still is, and so we hold the tension as a positive marker of care and interconnection on this planet, until we can have simple and pure pleasure again. Like with HIV: for those with access to PrEP, sex got to take on a new meaning in a post-PrEP world. Sex truly (nearly) without risk! What joy! But, with COVID, we aren't there yet. And so: tension. How beautiful! Because it means we give a shit.

And here's the other thing: Humans always fuck up! All of us! And so we need systems with robust protections. Like a concert outside with vaccine checks! Because, when one thing fails (oh, they didn't properly check your vaccine status), you're still at an outdoor venue which is way lower risk! My public health brain (very much not my formal training but very much my faggot-sex-brain training) is about systems robust to failure. You assume a human failure will happen at some point; when that happens, what other interventions will catch it to keep people safe? Because you can't rely on perfection, and you can't trust that nutty people won't act in bad faith (they will). So nerdy bureaucratic shit like public health systems robust to individual failures become actually a queer ethic of care!

“Systems robust to failure” is also a great way to describe BDSM! So, in some ways, you have made it your mission to guide people towards a more precise, careful, and accurate way of using language to understand viruses. I’ve seen you on Twitter calling people out for describing COVID’s desire, or its morality. The book contains an entire essay, “On War,” exploring the horror, not to mention futility, of “fighting” a virus using the language of war. Paradoxically, your entire writing career, from Capsid on, is about using poetry and metaphor to experiment with how humans think and feel about viruses. And earlier in this interview, you said, “this virus needs us.” Which is it, Joe?!

Susan Sontag asked us—in Illness as Metaphor—to remove metaphors entirely from our thinking about bodies and illness. She called being ill with a disease like cancer so thick with metaphorical thinking attached (at the time, a disease of “repressed feelings”), a “double illness,” the sickness, and the metaphors.

I argue, in the book, that pathogens, bacteria, viruses, and fungi, are so small that they’re impossible to talk about without metaphor. When you think about staph bacteria, do you think about a single-celled gram-positive bacterium, or a wound? And even the word staph relates to the shapes of grapes on a vine, a metaphor for how the bacteria look under a powerful microscope.

Coronavirus? Because, under an even more powerful microscope, it looks like a crown. This is metaphor baked into the language at such a profound level it cannot be removed, as Sontag might ask.

So, it becomes not about a language devoid of metaphor, but which metaphors we choose. For HIV, in Capsid, I had to understand that virus (one I’d grown up terrified of) as something … almost like a lover. My life had given me the circumstances of many people I know who seroconverted. And I needed to love myself as HIV negative, or positive, both; to love the virus that might have already been in me, because when HIV infects you, it does become a part of your DNA.

In this collection, the main undergirding metaphor I asked us to infuse in our thinking all the way to the level of our language is care. If so much language around pandemic, plague, and viral infection is driven by war (as we show), how can we change that language to be built from care, connection, and community, even in the face of unprecedented and risk-filled times? Because, whether it’s pandemic or climate change or fascism, we live in risk-filled times, and living well in them means resisting together and insisting on the right to care for every living person.