There’s writing that’s keen to demonstrate what it knows, and writing that’s eager to show you how it thinks. I don’t mean this as a binary, just as two big presences in my reading life, and it took me entirely too long to discover the singular joy of the latter. How expansive it is, and at its best and most singular how knowingly vulnerable.

Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, a 2014 collection of essays personal and reported, is a deeply affecting example of this type of writing not only because of its theme of understanding the pain of others, but because Jamison makes such stories of pain at once individually significant and part of a set of stories many of us tell ourselves about hurt. It raises new questions about precisely who hurts, how, and offers refreshing suggestions about how who is hurt by the assumptions we make about either question.

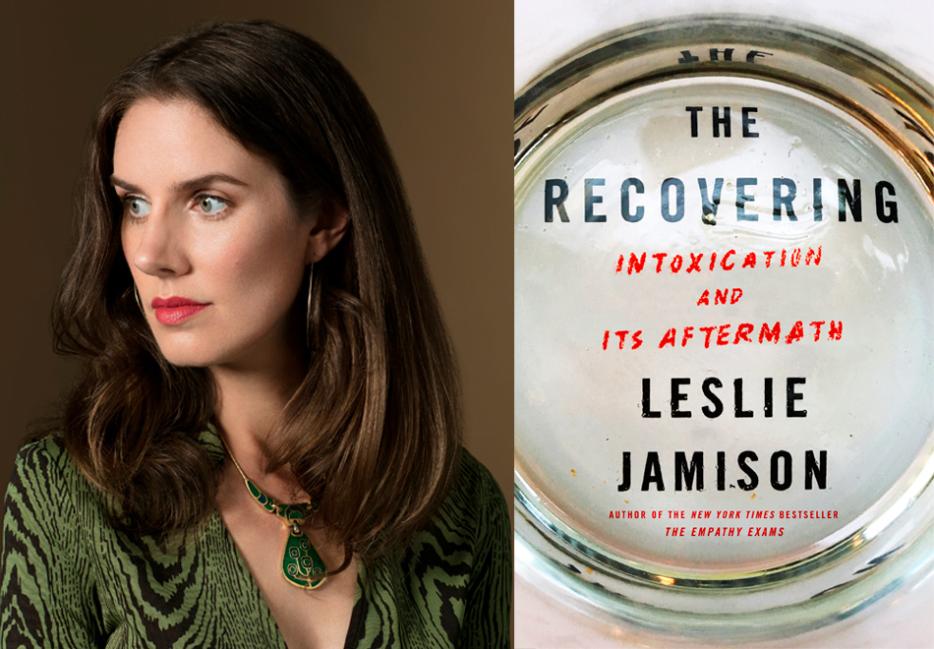

It’s this pretext that makes her latest book, The Recovering (Little, Brown and Company), the compelling addiction anti-memoir that it is. It carries you through her own experience with alcohol dependence in her mid-twenties; her hard-fought-struggle to reckon with it; and, as I would imagine she’d suggest, the harmful limits that accompany seeing addiction filtered through the lens of just one person’s experience. The 400-page book pulls from the lives of people famous and obscure; dead and alive; successful and spectacularly not so in the daily project of sobriety.

Chantal Braganza: You mention in the book that your first novel, The Gin Closet, was a way of writing about your addiction, if not directly.

Leslie Jamison: The Gin Closet was the first time I wrote about any kind of substance dependence. There was a division of labour among the characters. There was one whose life, externally, more neatly lined up with my own, and she had a certain relationship to drinking.

But I gave the dependant relationship with drinking to this other woman who looked nothing like me. She was older, lived in a trailer in the desert, and was drinking herself to death. She had this closet where she would go to get drunk.

It wasn’t that her drinking didn’t look exactly like mine. It was more that there was some part of me that could sense that the way I wanted to drink—if I followed it as far as it would go—would take me to some place like that, that fully and that destructively. I mapped that speculative self onto a character, who was explicitly more dysfunctional than I was at that moment.

Part of The Recovering came from a PhD dissertation you did. Did the book itself have another original form?

I think of the genesis of the book as the confluence of a few different rivers of writing. One of was my dissertation, and all of the research going into it: it was an exploration of writers who had lived through addictions—in some cases died of them—who’d turned their addictions into art, and some who created art from a state of sobriety and recovery. It looked at how the narrative of addiction and recovery is shaped, and what their sober creativity looked like.

But from pretty early on I knew the form I ultimately wanted all of that work to take wasn’t a scholarly monograph. I wanted it to be this hybrid work that would bring my story into conversation with many.

How did you describe this book to people while writing it? Did you feel the need to put qualifiers on what might otherwise be seen as “just another addiction memoir?"

I’d say it’s a book about addiction and recovery that tells my story, and the stories of many other people, but also interrogates the genre of the addiction story and how it’s structured. What we ask from it. What we want from it. That idea of doing the act of storytelling—whether it’s mine or someone else’s—and interrogating whether that act of storytelling works, really feels like kind of two core elements of the book that I would try to find some concise way to approach.

I remember a job interview where they asked what kind of project I was working on. I remember this guy saying several times, “I just don’t get it. I just don’t understand the book that you’re describing.” It was one of those Chinese finger-trap things where the more aggressively bewildered he was, the less capable I felt in describing the book in any kind of meaningful way.

How about the original name, Archive Lush?

I filed it under Archive Lush really even before I’d written much of it. Much of that time I was writing it with The Recovering in mind. I loved that title from the beginning. It evoked something expansive, and a little strange. A little like a horror movie, like The Shining. And it evoked both the idea of recovery as this ongoing process.

I also wanted it to bring up this idea of recovering stories from the margins. For example, George Cain’s book, Blueschild Baby, had largely been forgotten.

Cain is one way that you point to racialized addiction narratives, and how the world has tried to shape them. Specific to Cain’s story, how did you position yourself in relation to this?

I really responded to his book. It acknowledges the ways that addiction has been constructed as part of a really toxic political rhetoric that was really just a way of dressing up racial persecution—and at the same time still a deeply destructive, difficult experience.

I was also moved by the fact that he had chronicled addiction so artfully, with such subtlety and acuteness, but he hadn’t managed to transcend addiction in his own life. Self-awareness can be profound and create really meaningful art, but can’t necessarily save you. And telling the story of addiction doesn’t always save you from the experience of it, either. His story felt like an important part of illuminating that.

You spent so much time in archives to write about authors’ lives. Is there a document that sticks out in your mind as piercing?

It isn’t a specific document, but a pattern. When I first plunged into Charles Jackson’s archives, I thought I’d find accounts of his drinking, or traces of his drinking in his personal letters. And there are some. But what I was really struck by, and this made more sense once I realized what was going on, was that his drinking was largely absent from his correspondence, but it was all over his wife’s. You would read letters that Jackson and his wife had each written from a similar set of months, and he’d be going on about how he just couldn’t get going on this new book, how it was really hard for him to write, he didn’t know what he was going to write next—just this kind of stymying megalomania. All of the letters from his wife at this same time would be like, “Charlie had a terrible relapse, I don’t think this is ever going to get better.”

And once you notice the pattern, it was like, of course: he’s not able to confront this or articulate it. But his wife, who actually had to deal with cleaning up a lot of his messes, she’s writing about it more openly and candidly. That kind of simultaneity and divergence.

Why is it so hard to write recovery well?

When you’re writing recovery, you’re surrendering that primal vehicle of narrative—of things being wrong and broken.

There’s something about happiness or wellness or positive states that is more aesthetically challenging than states of difficulty, and I think part of it is the danger of flattening positive states into something bland or boilerplate or Tolstoy’s idea that all happy families are alike.

I actually think the Tolstoy line false. It’s not so simple. It takes more effort to excavate how things got better; it’s really hard to show consciousness and all those subtle gradations, even when overall what you’re portraying is a more positive state.

Addiction runs in your family. Have other members of your family read this?

Everyone in my family has. I definitely gave them the chance to read it. if I’m writing about anyone, I try to give them the opportunity to read it. Not that I give people veto power, but I want to give them the opportunity to talk about about it.

My brother said that it really helped him understand the fact that he wasn’t addicted to anything. It clarified what the experience of addiction was like by putting his own relationship to booze into sharper relief. He likes single malt scotch and has a huge collection, but he told me the book helped him understand my relationship to this daily obsessive state. It was interesting to me that someone could relate to it in an opposite way—that someone could read an account of addiction and find it a tool of illumination rather than resonance.

This is definitely more a comment than a question, but food feels like such a huge presence in this book. I haven’t stopped thinking about the sweets, breakfasts, and what you call the “odd flavour pairings of recovery” since.

I always find myself obsessed with bodily experience and sensory experience and food is a really core part of that. Food often shows up in my work as this stage on which a lot of things play out. What does pleasure feel like? What does indulgence feel like? What does self-restraint feel like? What does self-punishment feel like? Food becomes one of the ways I ask those questions.

I had a job at a bakery when I was in early sobriety, so a lot of my memories of that time have to do with showing up to work, the landscape of that little shop, and the ways I found that work saving.

When you give up booze—and booze is what you’re trained to understand as your source of release in this world—you’re on a desperate quest to find it in other places. I’m not the only sober alcoholic who has a really intense relationship to sugar. I think sugar really does have a role to play in early sobriety. I happened to be working in a temple of sugar at the time, so it only brought it out more fully.