William T. Vollmann’s Rising Up and Rising Down, an essay on the human impulse to violence, runs seven volumes and 3,352 pages. I haven’t read it. I don’t know anyone who has. I assume Vollmann has read it, but where would he find the time, between working on a five-volume novel cycle on the history of North America called Seven Dreams, or the 1,200-page study of a small town on the Mexican border that no one has heard of, and the book about Japanese Noh theatre? Plus, he paints.

Like Thomas Piketty’s Capital or the Knausgaard My Struggle series, Vollmann’s books are the ones you will get around to, eventually, one summer or long winter, maybe next year, if only to see at what all the fuss is about, or to reward the man for his diligence. All you need is a nudge, some kind of hook. This is your hook: Vollmann claims he’s done writing books.

“This is my final book,” he says in the preface to a new volume of short stories (short?) called Last Stories and Other Stories. “Any subsequent productions bearing my name will have been completed by a ghost.” It sounds like a ruse, coming as it does from a man who, when he’s not sleeping or undergoing dental surgery, is assumed to be writing. It might be a metaphor: from now on I’m a different writer (after all, he still owes Penguin the last installments of Seven Dreams). But whatever he’s up to, it’s worth using the pause to take a peek, finally, at his work up to this point, if “peek” is the right verb, which it isn’t.

The Vollmann library calls for stamina, but that’s not quite right either: the novels and non-fiction alike are fluid, and fluent. At 300 or 700 pages in, you wonder if they’ll fall apart under their own weight, but they don’t. Like Herman Melville, Vollmann has a simple storyteller’s instinct for the impossibly long adventure tale. Even the boring parts grow on you. What carries a Vollmann book is the author’s attention and sincerity: whatever’s happening on the page, you believe that he believes it’s important and true. It’s what David Foster Wallace most admired about him, besides the crazy output.

But where to start? First we might as well get a complicated and idiosyncratic biography out of the way. Vollmann was born in 1959 and lives in Sacramento, California, with his wife (an oncologist) and a teenage daughter. Like Kafka, who also aspired to truth on the page in its strangest, dream-like forms, Vollmann once worked for an insurance company. In his 20s he went to Afghanistan to write about the mujahideen and fought alongside them against the Soviets, until he came down with dysentery. He wanted to help them by telling their story, as Orwell had done for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War. He covered the war in Bosnia as a freelance journalist, and saw two of his friends killed by snipers. In neither case was he in pursuit of some cowboy thrill. In The Paris Review, he was asked about the appeal, for a writer, of going to war zones. “There’s no appeal in it,” he said. “It’s not fun. If it were I would be shallow, or else a monster.”

On assignment in Thailand for Spin magazine in the early ’80s, Vollmann met a teenage prostitute, bought her out of servitude and rushed her to Bangkok, where he enrolled her in school. “I want to take some responsibility and act as well as write,” he told the Review. “I don’t mean to be an actor, but rather to accomplish things… do things that will help people somehow… things like kidnapping the sex slave.” He is known for his fondness of (or obsession with) sex workers, has written about them in his stories, and has promised, if he ever wins the Nobel Prize (he often turns up on the yearly long list) that he will give the prize money to prostitutes. Also, the FBI thought he might be the Unabomber. (Punchline: he wasn’t, but his file—which runs a Vollmannesque 785 pages—claims “anti-growth and anti-progress themes persist throughout each VOLLMANN work,” a fascinating bit of literary criticism from a spy agency.)

Vollmann crosses and muddies the lines between candor, idealism, naivete, and creepiness enough for some readers to justify ignoring his work. But in any case he can never be accused of hiding behind a sterilized, authorial invention: “It’s always easier for people to characterize the writer rather than the work,” he has said. “Because the work they would actually have to read.” And it’s true that in reading Vollmann you encounter a hyper-vigilant weirdo on the page, and that’s part of the appeal: he’s not trying to snow you, to make himself look good. What he thinks is what he writes, a gap that so many writers find so hard to bridge. So to read Vollmann, the point is just to start, but maybe not at random. There are a few traps out there.

The Vollmann Gateway Drug

The best place to begin is with the 2005 novel Europe Central, which is actually his 12th work of fiction and the first (so far) to win the National Book Award in the U.S. It’s a war story in the way that the Iliad is a war story, which is to say that it’s really about how men and women make choices in impossible circumstances, how they betray each other and their principles, how they love before they die, if given a shred of a chance.

Formally, Europe Central is challenging until you get the hang of it. It is a series of short stories set in Germany and the Soviet Union before, during, and after the Second World War, but at its heart it is a doomed loved story involving Dmitri Shostakovich, the Soviet composer who spent a career under Stalin’s thumb, and Elena Konstantinovskaya, a translator who is married to another man. The composer, too, is married, and must decide whether to follow his heart or his conscience.

There are scores of other characters, from history and from Vollmann’s imagination, including the German artist Katha Kollwitz, the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, Stalin, and an opera-obsessed Hitler whom Vollmann calls the “sleepwalker.” Early on we find Hitler in Beyreuth, at the opera house built exclusively for the work of Wagner, his hero. “He gazes down across the empty seats,” writes Vollmann, “which resemble the keyboard of an immense typewriter upon which he might compose any musical score he pleases.” The score he composes, of course, is the war in Europe and Russia, a work of art which will rival Wagner’s Ring cycle, in Hitler’s mad estimation. For Stalin, too, art is a weapon, and this is where Shostakovich comes in: as the Soviet Union’s most famous composer, it is the Kremlin’s expectation that he will write music to serve the cause, to advance history. In other words, socialist realism, or propaganda. The love story in Europe Central is shadowed by Shostakovich’s artistic dilemma: will he write from the heart, or write what’s expected, in order to survive?

From time to time the author himself shows a hand, and reveals his purpose. “Most literary critics agree that fiction cannot be reduced to mere falsehood,” he writes in one of the opening chapters. “Well-crafted protagonists come to life, pornography causes orgasms, and the pretence that life is what we want it to be may conceivably bring about the desired condition. Hence religious parables, socialist realism, Nazi propaganda. And if this story likewise crawls with reactionary supernaturalism, that might be because its author longs to see letters scuttling across ceilings, cautiously beginning to reify themselves into angels. For if they could do that, then why not us?”

This is the Vollmann style: call him post-modern but really he’s a 19th-century Romantic, tied to his desk chair with a rope like Balzac, swearing he won’t finish until he has 800 pages soaked in candle wax. If you’re not in the mood it’s too much: rich food, indigestion. But if you are, it’s a banquet, even if some of the dishes are deliberately overcooked.

Seven Dreams

There are four novels in the series so far. The first, The Ice-Shirt (1990) is practically a novella at only 345 pages before glossaries and footnotes. It is a work of historical fiction centering on the arrival of Norse Greenlanders in North America, and their encounters with First Nations, modelled on the Icelandic sagas. The narrator is a Vollmann surrogate called William the Blind, who is ageless and holds a long view on human history, and who acts as a Virgilian guide.

The second volume, and the best in the series so far, is Fathers and Crows, about the French presence in Canada in the 17th century, in particular the Jesuit missionaries who made it their business to “civilize” the natives with tragic results. It was Fathers and Crows (1992) that first twigged the FBI to the possibility that Vollmann might be the Unabomber. Their assessment was that his book favoured the Iroquois (an uncooperative, occupied nation of anti-government terrorists) over Champlain and the Jesuits, who represented stable, governmental order over chaos. As Vollmann has made clear since writing about his FBI file in Harper’s, he holds no grudges, save the fact that they’re surveilling citizens without due process, and the fact that the FBI clearly didn’t read Fathers and Crows.

It is an unsentimental novel without heroes. In an interview for Hazlitt, Joseph Boyden said that Fathers and Crows “had a big influence on me” in the writing of The Orenda, which is a more tightly focussed and elegantly imagined story about the Iroqouis, the Huron, and the Jesuits in that time. Vollmann’s massive volume wants to be about that and everything else, including a few dozen hold-that-thought pages on the founding of the Jesuit movement by Ignatius of Loyola. “This book,” says William the Blind, “is the story of how the Black Gowns and the Iroquois between them conquered the Huron people. With its weight of antecedents and obscurities, as I admit, the tale is an ungainly one, like the patent letter in 1639 by the Grand Roy of France, Louis XIII…” and so on. And yet it works, as if concision would risk minimizing the high stakes of the story. It has the same appeal as watching a DVD box set in one sleepless sitting.

The Dream novels are tightly researched. Vollmann spent time in the Canadian arctic, living with Inuit families while working on The Ice-Shirt and Rifles, the fourth installment. He almost froze to death and at one point set his sleeping bag on fire in an I’m-from-Sacramento effort to dry it out. The book includes scenes from the modern North (William the Blind, as I say, holds the long view) and in Fathers and Crows we see Champlain’s travels against Vollmann’s own visits to 20th-century Montreal where, of course, he meets prostitutes. It’s hardly slapdash: for many First Nations people, he says, not much has changed in 500 years except the scenery. Like David Foster Wallace, the man likes his footnotes, and with Fathers and Crows they amount to a kind of narrative sidecar, as historians send him frantic memos about his handling of the facts, which he happily prints.

If all goes to plan, there will be books to come on the Plains Indians in America, and the battles between Navajo natives and the oil companies. The problem: these baroque and detailed books reward re-reading, and with sleep and dental appointments I don’t see how I can fit it in.

The Non-Fiction

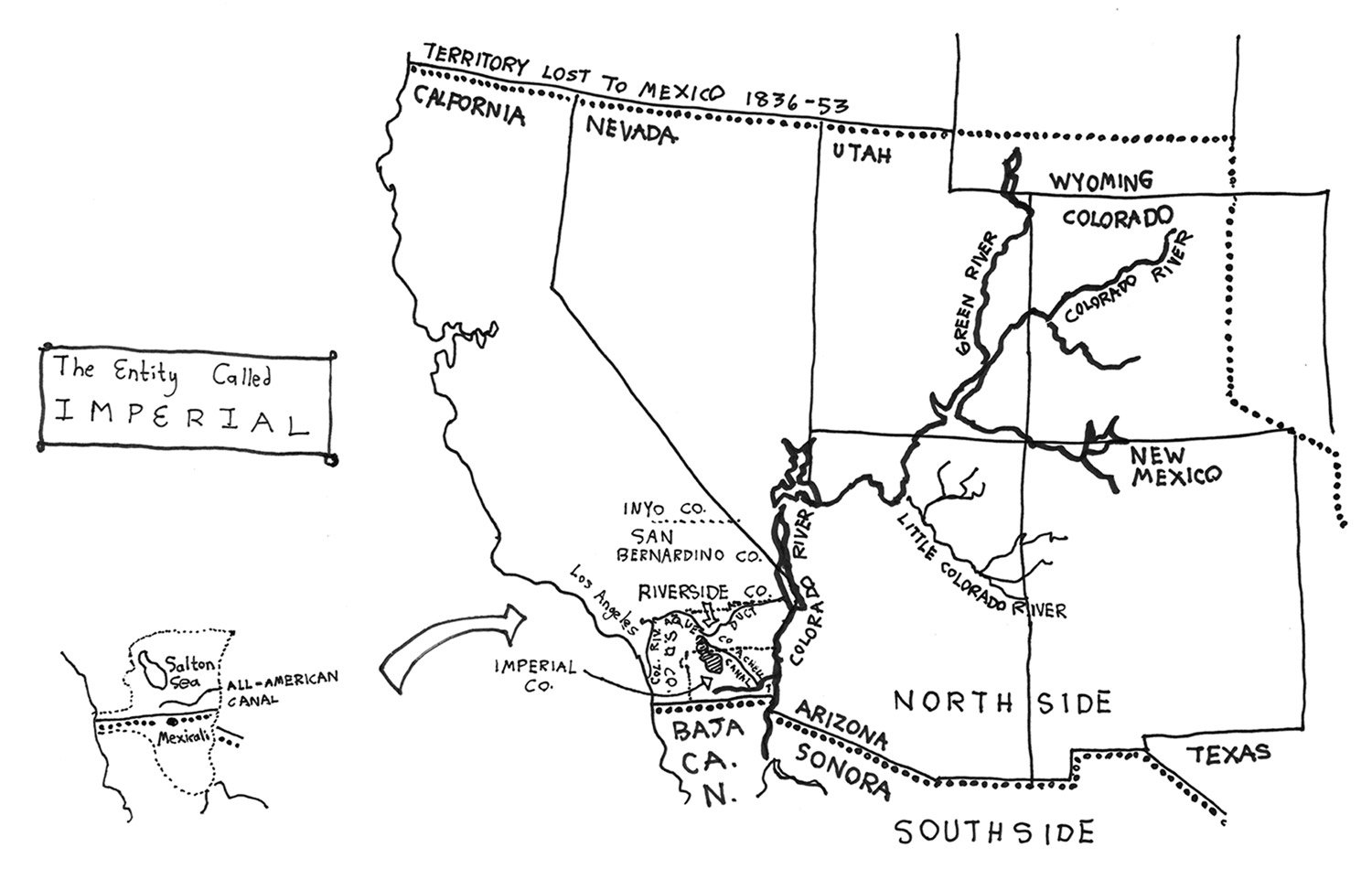

One risk in starting Vollmann at random is to pick up Imperial as an introduction. This one requires a two-month commitment to get halfway through, after which you’ll need certain evenings over a year. But it may be Vollmann’s masterpiece. Imperial fits Vollmann’s great theme of grand ideas that fail due to human hubris, but unlike in his novels, this failure is real and ongoing.

The book is the extensive (no surprise) biography of a place called Imperial County, in southern California, at the Mexican border. It is a place of illegal migrants, hardscrabble farming, boneheaded capitalism, and a version of the American dream that’s been shuttered until further notice. The place is dry and polluted. Much of the book’s beginning (meaning several hundred pages) has Vollmann charting the filthy waters of the New River up to the Salton Sea, an inland body of salt water that was created accidentally just over 100 years ago by an overzealous irrigation project. Dead fish, sewage, caustic chemicals, typhus, and rumours of dead bodies follow him and his good sport of a river guide in an adventure undertaken for the sake of verisimilitude and whatever it is in his character that previously led him to Bosnia and the Arctic: not quite gonzo, not quite journalistic arrogance, but something more genuine and likable. Vollmann takes on projects with a shrug because no one else is going to.

Consider the pitch to the publisher: Imperial is an exhaustive 1,200-page study of a small, exhausted square of America that nobody has heard of or cares about, with hand-drawn maps. Whatever the commercial considerations (Vollmann does sell books, to more than a cult following) the result is fearless. “Non fiction can sometimes go deeper,” he said of Imperial, “by eschewing the sometimes dangerous luxury of ‘readability,’” which describes the work in spirit but not in fact: it’s actually a page-turner, despite all readerly instincts. “Imperial is a boarded-up billiard arcade, white and tan; Imperial is Calexico’s rows of palms, flat tan sand, oleanders and squarish buildings, namely the Golden Dragon restaurant, Yum Yum Chinese Food, McDonald’s, Mexican insurance; Imperial contains a photograph of a charred building and a heap of dirt… Imperial is a map of the way to wealth.”

You think you know long-form non-fiction, and then you come across this addictive monster. The closest comparison, in the category of epic, subjective journalism, may be Rebecca West’s 1941 Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia, which similarly purports to tell everything it knows about a place on a map, and succeeds as a human chronicle of how we’re programmed to blow it, blow everything. “Only part of us is sane,” writes West, “[t]he other half of us is nearly mad… and wants to die in a catastrophe that will set back life to its beginnings and leave nothing of our house save its blackened foundations.” Imperial has a similar moral, but is told in a more homespun, tender, even cheerful American fashion. The two books would make cozy companions, if you have two years (Black Lamb is 1,100 pages).

Of the rest…

Expelled From Eden is billed as a William T. Vollmann “reader” and carries excerpts from a number of the novels and non-fiction pieces, plus a reading list of modern books he likes (he is a fan of Sigrid Undset’s Kristen Lavransdatter, set in 14th-century Norway), but forget it. There are CDs of excerpts from Wagner operas, but unless you’re willing to face five hours of Tristan und Isolde like a man, the best-of disc will be meaningless noise. Read the novels.

The Atlas is what it sounds like, a collection of short stories, travel reports, and prose sketches that describe, in some detail, the world according to William T. Vollmann. “Too much contemplation of any object, however unwilling the gaze,” he writes, “may reveal a secret.” This could pass as the man’s mission statement. Many fans say The Atlas is the place to start. I haven’t read it.

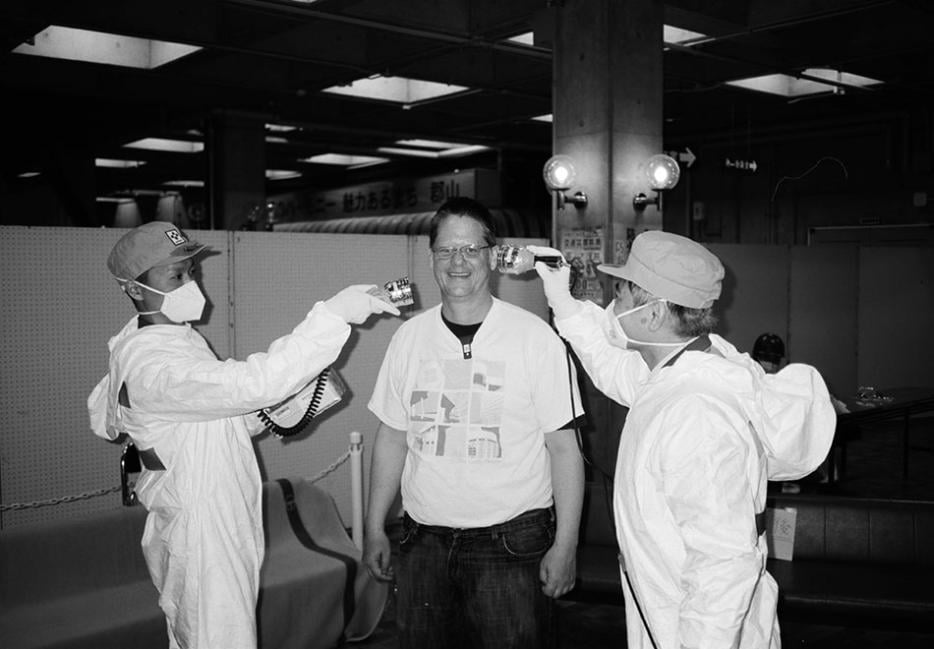

Kissing the Mask: Beauty, Understatement and Femininity in Japanese Noh Theater With Some Thoughts on Muses (Especially Helga Testorf), Transgender Women, Kabuki Goddesses, Porn Queens, Poets, Housewives, Makeup Artists, Geishas, Valkyries and Venus Figurines, from 2010, I haven’t read either but feel, from the subtitle, that I have.

Last Stories and Other Stories. Vollmann as he is now, thinking about death. Imperial is a book about borders, manmade and otherwise, and so, in its chilling way, is Last Stories, where, in some of the more startling and Poe-like stories, the dead and the living fall in love. They reach to each other over barriers that they’re not supposed to cross. In “The Forgetful Ghost,” he writes, “I’d wanted to learn to die, but instead was condemned to try unavailingly to teach a ghost to live. Did it follow that perhaps I could help him forget that he was dead if he in turn taught me to forget that I lived?”

The best are the first two stories: realist heartbreaking tales from the war in Bosnia, told by a writer who still mourns.

What I’m waiting for and would buy from my bookseller...

Anything else he writes, up to and including a volume of his grocery lists, which I assume would include the colonial history of arugula.