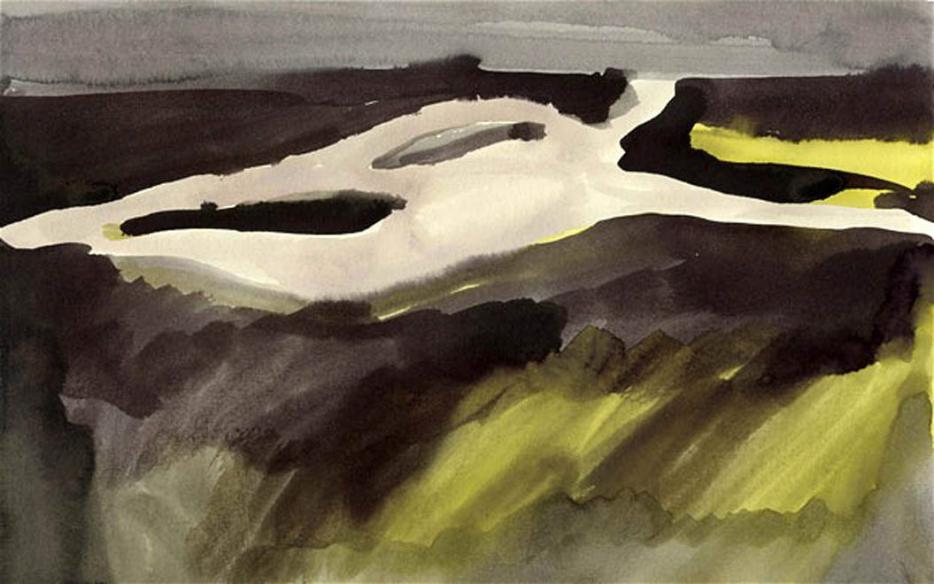

Reading Leanne Shapton’s Swimming Studies feels like meditation. The artist-writers’s account of her early career as a competitive swimmer at the near Olympic level magnifies the anxieties attendant to working very hard at something one’s very good at. And those that accompany the murky waters of adolescence.

Shapton quit swimming when she was 17, and the memoir deals with the dissolution of that earlier self. The serious athlete lives a life of routinized desire, of extreme physical and cognitive repetition designed to prepare her for extraordinary performances; to break with that specific kind of life, defined so readily by practices, coaches, and trackable goals is like a suicide the body might survive. The woman goes on to be an acclaimed art director, designer, and painter, but the athlete dies. I met with Shapton very early on a drizzly Sunday morning after her reading at the recent International Festival of Authors in the lobby of her hotel. She was hoping to be on a flight for New York shortly, but the approach of Hurricane Sandy threatened to scuttle her plans. We drank coffee and looked out the large windows of the hotel lobby, where we could see the rain pummeling the last few golden leaves out of a tree.

Your illustrative work seems very organic and spontaneous, there isn’t a sense of editing, of things being taken out. Whereas your prose seems very intimate and tight, and like a lot has been taken out. It’s very minimalist.

Well, with the illustration work, as it relates to my swimming, I realized I do it like laps—that’s my practice. I’ll just sort of do a hundred repetitions of that view from my window, or painting the same vase, or something like that. But with prose, the prose that I like reading is very pared down, is very edited. The nice thing about illustration is that even if you look at three drawings of the same thing your imagination is still working, and with prose if you write the same thing three different ways your imagination will not work. You just go, “I know, you already said that!”

So I really wanted to leave space for the reader to go, “Okay, I get it, she didn’t have to nail that too hard.” With drawings—I don’t think you can do with writing—you can show a different kind of reading each time. Morandi drew the same kind of still life over and over again. I mean, I guess you could compare that to a writer that finds the same subject matter, and yet we never tire of it, but since I don’t write as much, I really can’t do that. It was also my first attempt at writing so I didn’t really know what my style was. I just wanted to make it as clear and minimal as possible.

There are those two references to Alice Munro—

Which are the two? I remember the one...

At one point in the book you are going to bed, reading Alice Munro stories, I think you’re in a hotel. And there’s another earlier one, too.

Oh, yeah.

I noticed it because you talk a lot about artists in the book, but she was the only writer. And I was like, is this a clue?

Yeah, I love her! Jo Ann Beard, too. But while writing the book I was looking at graphic novels and how people like Seth, Gabrielle Bell, and Vanessa Davis write comics. It’s unstructured, it goes back and forth in time. Even besides the fact that it’s accompanied by drawings, it’s much looser. It’s memoir, but it’s not Memoir—y’know, like “I was abandoned”—it has this wonderful, light touch. And I kind of looked to those writers, graphic novelists, because they were very confident putting their own personal stories out there without going “why is this worth it?” Because a lot of memoirs that are out there something big and grave and momentous happens and in mine... I try not to call it a memoir, but nothing really tragic happens at all. I was like, well graphic novelists do it all the time, and that was hugely liberating.

Did you decided consciously in the beginning that you were going to write the whole book in collaged scenes in the present tense, or did that come out of the process?

That came out of the process. I had all the scenes and then it was a case of, “What am I gonna do? What’s my structure?” You know, “what’s the centre of it?” And then I was on a kayak, and I reached into the relatively still water and it all broke up. And I realized I wanted that to be my structure. Because structure can be anything!

I read Blood Horses by John Jerimiah Sullivan a few months later and it made me feel even better that you could have a very unconventional structure, with weaving. Me and my editor from London, Helen Concord, talked a lot about weaving. And so that relaxed me into deciding, okay, so the structure’s going to be like this kaleidoscopic shifting focus. Because, you know, in water you get magnification, you get all that stuff, and I thought, I’ll just make it that. And if people ask, that’s the structure. Because it made sense to me that it would be watery.

Would you say that you still have a competitive urge?

No, it’s ebbed since then. And even when I was swimming, I wasn’t thinking, “I gotta be the best!” I was good, so it was like, the only way to go is to get better and beat people. And so that weirdly sort of conditioned my female friendships. It really wasn’t good, because I didn’t really have strong female friendships until I was in my late 20s. But am I competitive now? Not really. I’d say it’s probably mellowed into ambition, if it can mellow into ambition. But yeah, I don’t really set anyone in my sights the way when you’re swimming, you’re like, “Oh, I have to beat that girl, Stephanie.” That said, I get really upset if I lose a backgammon game. I still kinda want to win. I play competitive charades with a group of people in New York, and I try not to look at the score.

Charades is very important, though.

The stakes are high.

One thing that I definitely noticed when I read the book is that you didn’t really have any female friends. But I didn’t think about it in terms of competition. You may have, and just not put them in the book?

Well, I was looking up to my brother, and there was not that much time for friendship with the friends who I did feel simpatico with, the kids at my arts high school, because I couldn’t stay after school. Until I quit. Then I’d bicycle over to my friend Chris’s house, but then again my best friend was a guy. And then there was my friend who I went to England with, who I was really close to. She’s called Jane in the book. But, yeah in those early days there wasn’t much bonding. It was funny, because I was trying to fit into a really specific world. In the chapter “Other Swimmers,” I really wanted to try to subtly explain how afraid I was of other kids. These kids were aliens to me! Like, what’s with the moisturizer and the licking of the arms? And I would see them as so exotic, and I don’t know why I wouldn’t—like I was so anxious, and I just wasn’t a relaxed kid. I mean, I was fine, I was well liked, it’s not like people treated me like an outcast. I didn’t lack for friends, but there wasn’t any close bosom buddy.

In the memoir you dance kind of delicately around the idea of depression. Both as a swimmer and later as an artist you appear to be very driven. But both pursuits are accompanied by this loneliness and sadness. Do you think those feelings are somehow important when you’re going after something? Or for the development of a talent?

I think it might just be me. I have clinical depression; I was diagnosed when I was 28, I guess. And I was always just a moody kid. I mean, I got depressed after I quit [swimming] the first time, which is totally understandable. It was like a complete loss of identity, I was on this track, training with an excellent Canadian team...

I was lucky enough to find, through a friend, a doctor who recommended Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for me, because he said I would “understand that it’s just work.” There is a lot of “what happened here?” and childhood and family stuff, but at the same time it’s more like “let’s try to strengthen your mental health,” and so from learning how to strengthen my physical health for so long I could get it, and he was right. That, along with medication, did pull me out.

Now I am happiest when I am in those zones of work. I don’t know that it’s necessary for good work, it’s just sort of... I either stave it off or funnel it. It’s actually kind of interesting to talk about, because I treat it so lightly. It’s just such a part of my thing, and it’s so interesting how many people are, like, a little bit depressed. It’s like, everyone I know! And I was so ashamed of being called clinically depressed for so long, and now it’s like, whatever.

It’s a pretty high number of people that live in cities that suffer from depression.

It’s a thing, and it has to be looked at in the face. I don’t know, it’s an interesting thing because you can really ruminate and really stew, and I guess the repetition is sort of a version of the rumination. But yeah, 2002 was a bad, dark year. I would never want to go back there again, but I’m not really afraid of it. Again, it’s not, like, a deep, deep—it’s a mild clinical depression. I haven’t had to up my dose since 2003, so…

I think it’s great that the book doesn’t treat your depression as this necessarily horrible, dark thing. Because for you, it isn’t really like a horrible dark thing--

It’s not, yeah.

—It’s just part of life.

I didn’t even think about putting it in [Swimming Studies] until I realized that I kind of had to bridge those years a little, and then I was like, “Oh yeah, that happened.” It was a funny incidence. I like when people are really frank about what’s going on with them. I admire that in other writers, I admire that in people in general. Everyone has a dark side, everyone has this... I’d rather people be super cheerful and then very forthcoming with their dark side, you know what I mean? I love when people are self-aware.