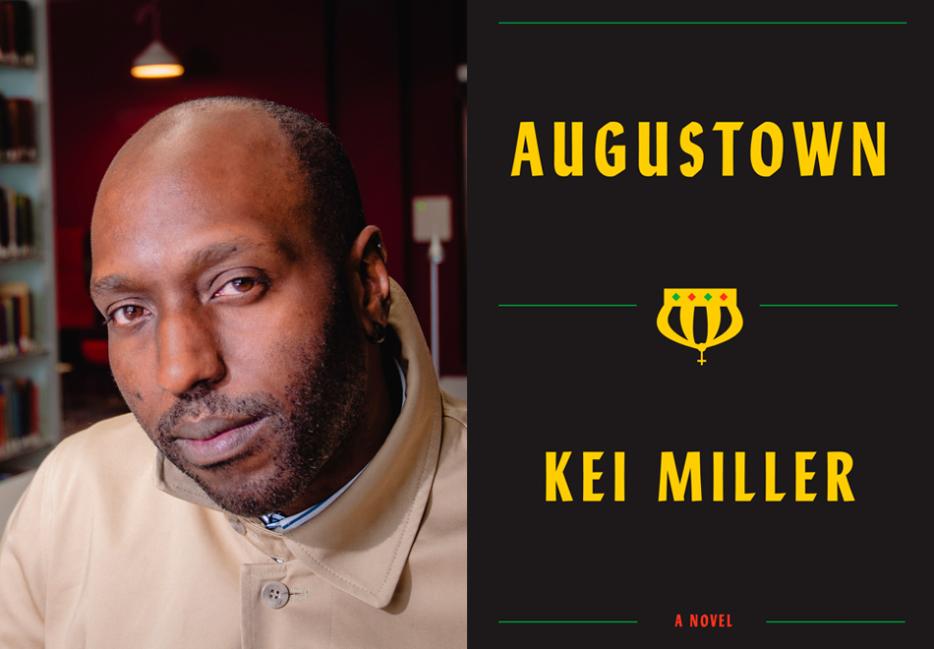

Augustown (Pantheon), Kei Miller’s novel about Jamaica, history, belief, race, and class, touches on a collective human desire to think about why we believe certain things. As Jamaica turns 55 this year, while also marking 179 years since emancipation from slavery, the book considers ideas and conceptions of freedom.

The context of the novel is the story of religious leader Alexander Bedward, a legendary Revivalist active in the early years of the twentieth century. He resisted oppression, called for what might now be considered Black power and preached to his many followers that they would all fly back to Africa. He was eventually sent to a mental asylum, but he supported Marcus Garvey and his ideas informed both Garveyism and the movement that became Rastafari.

With this historical background, the story centres around the story of Kaia, a young boy who is punished by having his dreadlocks cut off (a moment that is also based on a true story). All of the characters that make up the community of August Town react to this according to their beliefs. But as is often said in Jamaica, “Belief can cure; Belief can kill.” These beliefs are not so much connected to truths as they are connected to the stories we are told and tell ourselves.

Erin MacLeod: What to you makes the story of Alexander Bedward important?

Kei Miller: I think for me the appeal of Bedward is the appeal of many things that occur to me when writing. It’s always that kind of story that’s both right there but hidden. In a Jamaican context, I’ve always heard about Bedward, but always that story is told in a kind of derogatory way. My grandmother always told me about him. She would cackle, just laughing at what an idiot this was. I grew up with this idea: fascinated by Bedward because he was such an idiot. And very much inheriting that story that comes from the class that I guess my grandmother represents: educated, middle class Jamaica who want to rise out of that kind of ignorance that traps the folk.

I guess, probably later on, realizing what a big movement Bedwardism was. I suddenly thought that the people who followed him would have had a very different story and of course with that kind of story always, this massive amount of people who believed weren’t the people who wrote things down, who got a chance to tell their stories. They weren’t in possession of narrative. They didn’t have agency. And so it is just fascinating how to me this wide story of belief and the necessity of belief was hidden. And the other thing I thought—which might be slightly overblown—is that Rastafari would have been impossible without Bedward. Which probably is not quite accurate, but certainly I think Rastafari as it looks today is impossible without him. And I think that’s fair enough. Garvey gets all the credit of being the forerunner of Rastafari when it seems to me that the stream of Garvey had to meet the stream of Bedwardism for Rastafari to look the way it does.

I always think of Rastafari as a product of a perfect storm of influences. There was no one person or element that can be pointed to that created Rastafari, but it grew and continues to grow as a result of a range of factors, individuals and ideas.

That’s certainly how I feel. And Bedward just offers so much to Rastafari. The language of “zion” to me certainly comes out of Zion Revivalism, which is of course what Bedward is. So all of that discourse about Zion, about Babylon, about mysticism, the drum beat, which ends up as a Rastafari drum beat—doot doot do do do do doot doot—that is coming out of Revival, which means coming out of Bedward. The robes, the tying of the head. Bedward gives so much to what we know of Rastafari today and yet Garvey gets all the credit.

And then I was at a lecture with [Barbadian poet and academic] Kamau Brathwaite years ago when he was giving some key note lecture at the University of the West Indies. In that lecture he paused halfway through and said “It’s time to write about Bedward.” And that just struck me. It was off script, it was a heartfelt “why haven’t we talked about this man?” and that simple instruction stayed in my mind for years and years. I always thought was true.

One interesting thing about Bedward and Rastafari is, in both cases, the kind of derision of the belief systems that went along with both of them from a different class of individuals looking down on them. This derision is evident in the book. And obviously in recent times there's been a repetition of that very story, the very thing that happens to Kaia in the text. Can you talk a little bit about that? Maybe it is time to talk about Bedward—not to try to retell history, but to try to understand the derision directed at people who believe or think something different, perhaps something African?

Right. Well, I guess there is a broader thing that I wanted to do in the book. To me in some way it is a book written to middle class Jamaica. It’s a book written to where I very much am from. And I have always thought—and you know I think that Jamaica is a deeply, deeply racist society. It always amazes me that Jamaica never owns up to this—they never admit it. And part of it I get—the whole Jamaican discourse: no, we don’t have a problem with racism, we have a problem with classism. To me it’s just that our racism has gotten sophisticated. Values coming from colonialism basically suggested “be white” or “act white” or “speak white.” These were no longer, with the Black consciousness of the 1970s and the changing of the colour of the Jamaican middle class, perpetuated by a white upper class. The nice, Black stewards took up all those values and began to perform that same thing and the rhetoric of it changed. It was never directly said as “speak like a white person,” rather “speak well.” It is not “have hair like a white person,” it is “groom your hair well.” Obviously a lot of these values we have are about what is desireable or what is polite—I guess that whole idea of British politeness gets subsumed into Jamaican society. It seemed to me that all of those conservative values that we have are fundamentally based on race. And why don’t we talk about this? So a situation like that which happens to Kaia, to me, is obviously fundamentally racist.

I wanted to tell a story about class in Jamaica. In Kingston, August Town is in the valley. Mona is middle class and right above it and Beverly Hills is upper class and just above Mona—so there are physical elevations that reflect social stratification. I wanted to tell a story about how class operates, but how classism is never just classism. That the roots of Jamaican classism are based on race. And so when we say that we are being classist, we really are being racist.

The story of Bedward has him and his followers moving out from August Town. Your book has two separate situations in which the reader is taken back towards August Town. You make it clear exactly how you get there and what you pass to get to that space. Is there a sense that we all have to return to the past and follow that path backwards to understand where we are now?

That’s a lovely way of thinking about it. I’m stealing that—I didn’t think that at the time. Quote me as saying that because that sounds great! But that makes complete sense. One of the things I wanted to say about August Town is that thinking about what I imagine as that first march towards August Town, which I do talk about in the book. It is that [August 1838] moment of emancipation coming and August Town is the destination. Its very name says that it is the goal: this is freedom, the literal manifestation of this thing that we have been hoping for, wanting, so the place becomes celebratory. It itself becomes a monument.

It becomes a Zion of a type.

Yes. It is the freedom that they wanted. It is the August date, the August morning. And how that fails monumentally. It is a failure, but the freedom that they feel they have achieved is revealed as being shallow. They don’t have the tools to enact that freedom. They are not getting compensated for 400 years, they are getting nothing. So August Town was always bound to fail, was always bound to reveal that they are trapped in Babylon and this isn’t Zion at all. And it seems like that story keeps on repeating itself. So who journeys to August Town as a place of Zion and how does it constantly reveal itself? There is the system around it, that system incapable of making August Town a place of freedom or incapable of releasing its citizens, its residents from all the shit that it puts on them. I wanted that movement—thinking about the first march, but also how all these people keep marching back towards August Town, as if they are marching towards something, but as the book says, they never ever reach that destination.

This year’s anniversary of emancipation coincides with Jamaica’s fifty-fifth year of independence. How do you feel that a story like this resonates? I’m thinking in terms of communicating history or the way that history is told—the way that history creates stories that shape a sense of identity.

Obviously there is a kind of sadness that this type of story is still relevant. You know, probably more than anything, I am grateful that it resonates and yet sad that it has to resonate. But again, it’s just exposing the shortcomings of our emancipation, what was never achieved. It seems to me that emancipation is a time to be so much more reflective than celebratory because so many of the things that we wanted to achieve haven’t been achieved. And then again it becomes so complicated because of race. Because the middle class looks so different now. Because of the people who have become Babylon. It is not saying that no one has escaped, but that people who have escaped end up being invested in maintaining the system and continuing that oppression.

What surprises me again, and this is what you hinted at before: how this story keeps on playing out. Specifically, how many people recently have had their hair cut off or demanded changed? And this story of hair is not just recent. Of course Augustown is based on [Jamaican poet] Ishion Hutchinson’s story [of having his dreadlocks cut by a teacher when a child], but I also think of when Beverley Manley was first lady of Jamaica. One of the big stories that catapulted her into fame was that a school had disallowed a Rastafari child from attending. And this was a huge story at the time: she had to intervene and take him out and put him in another school. This was a part of the whole Black consciousness movement. You would think that a move like this by a Black woman, the prime minister’s wife, would say something about how we saw ourselves as an African descended people, but it didn’t really amount to much, because in the 1990s when Joan Andrea Hutchinson went to present the news wearing Nubian knots, that became such a huge fucking issue in all of Jamaica. And the rhetoric around it! Just how nasty of her, no grooming, no broughtupsy, “how she can put herself on the TV like that?”

This issue about hair hasn’t been resolved at all. Coming right down to last year, when this little boy is not allowed to go to the school. But what is surprising is the discourse that emerges in the midst of all of these instances. Always nasty, disgusting and, of course, people have no shame saying these things. Not hearing what’s behind it. It’s like [Jamaican pop star Sean Paul’s wife] Jinx saying to Usain Bolt the actual words “I wish he would go back to where he came from.” And not understanding where that rhetoric has been used before, where did she mobilize it from, what does it mean. The ways in which we always participate in racism and therefore how we continue what we are supposed to be emancipated from are always really surprising to me.

You have a character who is attempting to emancipate herself and she is cut down for reacting violently against the very racism that you are speaking about.

It couldn’t be a success story. She couldn’t escape at the end. Some way the system had to get to her, prevent her from rising. Obviously I’m suggesting that she is the Bedward figure. She is the person that is trying to rise and, in another way, she is going to be pulled down in exactly the way that I suggest Bedward is pulled down. This happens despite having the ability—and in a somewhat magic realist way in the book I do also suggest that Bedward actually does the ability to fly. It is never just about people picking themselves up by their bootstraps and having everything within their own capabilities to rise. There is always something around that pulls them back down.

It is interesting. The number of people who have written me angry about the ending is surprising. I mean in a good way—I think that really affected them. But reading and going “oh no, oh no,” praying that she doesn’t die, which is all very weird because I tell the reader that she gon die. It’s almost like people think this is a trick.

We consistently want to hear stories that deny what we know to be the case. But by telling stories, by looking at what creates narratives, that’s what creates change. It’s not about pretending—or forcing.

Hopefully. That is certainly what I wanted. You have to realize that these people are the kind of people who should be able to do good things and there are reasons why that just doesn’t happen.