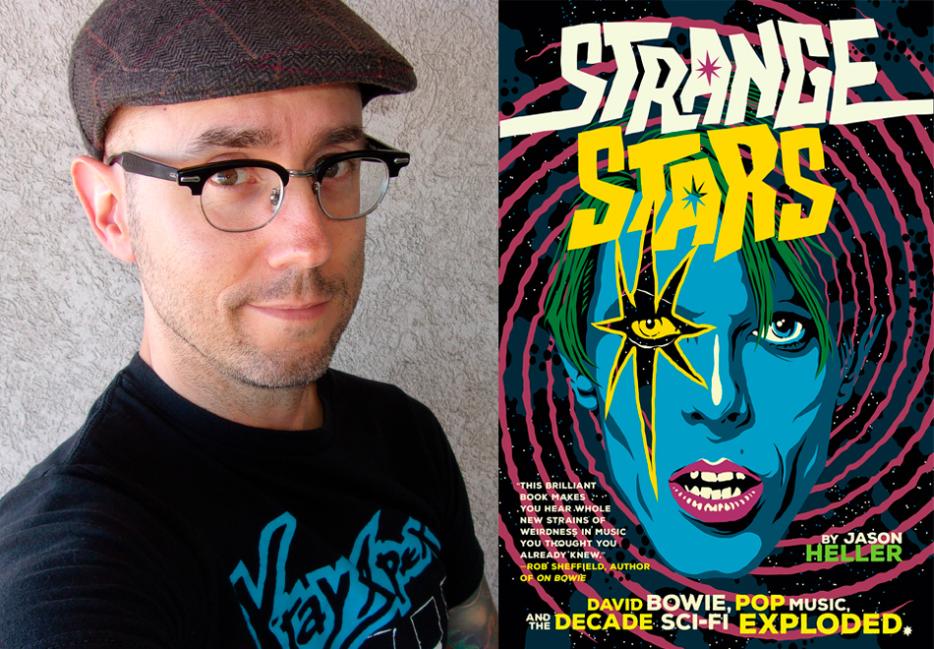

Jason Heller’s Strange Stars: David Bowie, Pop Music, and the Decade Sci-Fi Exploded (Melville House) explores a genre that spread across rock, jazz, disco, metal and funk: sci-fi. The cover image—David Bowie’s face against a starry backdrop—immediately contextualizes the musical use of a term that we’ve been comfortably attaching to genre work in literature, film and television for decades.

Heller, a Hugo-winning novelist, makes a compelling case for the importance of sci-fi to some of the greatest music of the seventies, from Kraftwerk to Sabbath to Funkadelic. Heller is a former record store employee, and it shows: he’s seemingly heard everything, and as I was reading, every time I thought I’d found a gap in his cataloguing of sci-fi music’s proponents—Hawkwind, say—I was usually about two pages away from his detailed exploration of the band’s relationship to British sci-fi writing legend Michael Moorcock.

The book can be used to generate an endless cosmic playlist, and perhaps most usefully, gives us a way of thinking about musical genre that transcends the usual categorizations: Heller’s book groups music according to the aesthetic and thematic concerns of the artists who made it.

Naben Ruthnum: I liked that you got into instrumentation as a component of sci-fi music—that this form of music is not just defined by lyrical content. This is especially obvious when you write about synth-centric artists such as Kraftwerk or Klaus Schulze. But earlier in the book, you talk about Pink Floyd leaning away from sci-fi music as Roger Waters took the reins. I thought this might be an interesting place to pin down a definition of sci-fi music. Is the Floyd shift away from sci-fi music a matter of refocused lyrical concerns, after the departure of original vocalist and creative force Syd Barrett?

Jason Heller: I think Pink Floyd definitely sought to redefine itself after Barrett’s departure, and justifiably so. They could have tried to replicate his mix of mythical whimsy and astrophysics, but that would have been a losing game—at the same time, they didn’t make a sharp left turn, but gradually expanded the scope of their lyrical concerns while retaining vague elements of the cosmic.

This is one example of a very tough struggle I had while conceptualizing Strange Stars: How do I define this stuff? Should I only include music with lyrics, and specifically lyrics that reference sci-fi works and/or tropes? Or should I also include music that’s instrumental but has a strong sci-fi vibe and even sci-fi-centric song titles? That issue dovetailed with another I was having: Do I restrict this book to pop music, so no jazz or classical, or do I define pop music on seventies terms, which would definitely include jazz, thanks to the huge jazz-fusion crossover of the decade?

I wrestled with all these things before realizing I should approach this a little more intuitively than giving myself hard-fast rules on what I could include or exclude. My working definition of sci-fi music while I wrote Strange Stars was simply: Music that was directly inspired by or paralleled, consciously or otherwise, what was going on in science fiction of all media during that time. I didn’t include classical music or soundtrack composers, as I felt that was something altogether different, a dynamic that functioned less organically and spontaneously than the back-and-forth between pop music and other sci-fi pop culture of the seventies.

On the page, British and American sci-fi had quite a different evolution, and as a result, UK and US sci-fi in the seventies and eighties were rather different beasts. Strange Stars tracks the differing evolution of sci-fi music in the UK and the States: SF music gained British traction before it caught on in America.

Just a note on SF vs. sci-fi as the terminology I use in Strange Stars: I come from the science fiction scene, where SF is definitely preferred, as opposed to sci-fi, which is viewed by some in a snooty way as something the uninformed or clueless might call science fiction—or the lowest class of science fiction itself. It’s such an insider-baseball argument, and I was writing this book for a general readership, so I stuck with the more recognizable “sci-fi,” regardless of any objections a couple of snobs here or there might have. Also, to a general readership, “SF” means “San Francisco”—and since the city of San Francisco is mentioned a few times in the book, I thought that a good ninety percent of my readers could potentially be thrown off by all the “SF”s in the book.

Ah! You argue that “Doctor Who” and other mainstream culture staples in the UK paved the way for sci-fi music on that side of the Atlantic, while sci-fi stayed cult in the United States until 1977, with the Star Wars explosion. Initially, I bucked against this argument—to me, American sci-fi has been part of the pulp lifeblood of the country’s culture since long before Lucas. How did you come to your conclusions on when sci-fi became undeniable in the States?

I think that may be an oversimplification of what I say in the book. I don’t say that sci-fi was underground in America until Star Wars—only that sci-fi music wasn’t very marketable as such in America until Star Wars came out, and when Meco’s disco version of John Williams’s theme went platinum, which opened the floodgates for sci-fi music on a commercial level.

Of course, Star Wars did elevate sci-fi cinema dramatically as well; almost overnight, sci-fi became cool instead of fringe, mainstream instead of niche, in a way it had never been before. There are many degrees of underground through aboveground, with each sci-fi medium being a unique spectrum, and those affected how and why sci-fi music was made in the seventies. And that’s what I explore in the book.

Got it. And as for Continental Europe—you talk about Magma, Kraftwerk, and many other European bands—was this branch of SF music distinct, and unified in any sort of scene, or were these just different groups with different stories? And did the evolution of SF music in Europe have parallels in European SF writing?

Well, I write at length about krautrock and how it was distinct, unified scene. As for European sci-fi bands as a whole being united in some way, no, it was more of a country-by-country thing. And most of the European bands were drawing from American and British sci-fi, which dominated the markets at the time, even in Europe. These authors—Moorcock, Ballard, Dick, Clarke, Heinlein, Le Guin, and so on—made up the canon of 20th century sci-fi as it was defined at the time, and the European sci-fi bands wanted to be part of that conversation. At least those who paid attention to the sci-fi canon and weren’t more ambitiously crafting their own sci-fi mythos out of whole cloth, like Magma.

You mention that sci-fi music in the eighties wasn’t so much about spaceships as “about technological advancement in mass media and the impact it might have on society.” Did this trend continue in sci-fi music? What is sci-fi music about now?

Sci-fi music tapered off in the late eighties and early nineties, barring a few outliers like Queensrÿche and Voivod, who reconnected metal with its sci-fi roots in totally unique ways. The music of the nineties wasn't as interested in science fiction, at least musically, with exceptions like Kool Keith's Dr. Octagon; it was a decade more about turning inward than pondering the outer unknown. But the 2000s brought a huge new wave of sci-fi music, from Coheed & Cambria to Deltron 3030 to where we are now, with Janelle Monae and clipping. being recognized for their sci-fi concepts both within the music industry and within the sci-fi community. And that music reflects some of the more pressing concerns about technology and the future that we have today: posthumanism, cloning, the internet, and a whole other host of themes that are more cyberpunk in nature. For the most part, it's metal, hip hop, and R&B that are carrying the torch of sci-fi music today, but those seeds were planted in the seventies when those genres first began channeling science fiction.

You credit your editor with keeping this book from becoming an encyclopedia of the bands and artists that fit into this genre, and I was wondering how you both made sure that you were writing the story of SF music, and not a catalogue of its proponents. Were there throughline arguments you kept in mind with every chapter? A conclusion you were aiming towards, or one that you started with?

I was being a little self-deprecating by saying I originally was going to write an encyclopedia about sci-fi music. My original proposal encompassed all of popular music from World War II on, with each decade comprising a chapter. It wasn’t going to be an encyclopedia per se, but it would have read a bit encyclopedically, since I would have had very little page-time to devote to each artist—I would have had to basically rush through and draw my conclusions more generally. So, my editor at Melville House, Ryan Harrington, asked me, “Can you narrow this idea somehow? And find a stronger narrative that runs through it?”

Bowie was always going to be the primary figure on Strange Stars, so it took me about ten minutes of brainstorming before I realized that zooming in on the seventies was the way to go. Not only could I bookend the that decade with “Space Oddity” in 1969 and its sequel, “Ashes to Ashes,” in 1980, I could probe the transition of sci-fi music from novelty to self-conscious art and back to novelty again. And in doing so, I was hoping to tell a kind of alternative history of Bowie’s life and career in the seventies, one that is often touched on in his biographies but never fully depicted—that is, Bowie as an author as well as an avatar of science fiction.

The book makes it clear that Bowie’s primacy as a figure of sci-fi music is undeniable—and his large role in your own cultural worldview seems just as prominent, from your brief discussion of your relationship to his music and Bowie-as-icon in the first few pages of Strange Stars. To what extent did your interest in sci-fi on the page and screen predate and feed into your developing interest in sci-fi music?

My earliest memories of science fiction are watching reruns of the original Star Trek with my grandfather when I was a tiny kid in the early seventies, and also shows like “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea” and “The Six Million Dollar Man.” Then Star Wars hit, and I was hooked forever. I grew up very poor, and all these images of advanced technology and humankind transcending their surroundings—and even their bodies—captivated me. A lot of people view science fiction as escapist, and of course that's anything but the truth. I was inspired to seek out science fiction novels, and I joined the ubiquitous Science Fiction Book Club, which advertised in magazines frequently back then. Between that and the public library, I was by the early eighties this precocious ten-year-old devouring Frank Herbert, Andre Norton, Roger Zelazny, Fred Saberhagen, Frederik Pohl, Robert A. Heinlein, and so many other sci-fi masters. The first sci-fi record I ever owned, though, was one I cover in Strange Stars: Meco's disco version of Star Wars. But by the early eighties, science fiction everywhere in music, and I remember Peter Schilling's new-wave hit "Major Tom" really grabbing me when I was around twelve. Of course, it's a song that stars Bowie's Major Tom, and I was getting into Bowie at the same time—so sci-fi music felt like some kind of vast, interconnected mythology to me, one that, in those pre-internet days, was something I had to discover on my own.