The Nairobi to Moshi bus left early in the morning, made its lonely way south through the plains. I had been instructed by my hosts to decline in case a fellow-passenger offered me a candy, because it was likely to be drugged, in which case I would be robbed and lose my luggage. It was the early 1990s and such was the fear for personal safety then. But my neighbour, a young Masai or Meru who was headed with goods for his father’s shop in Arusha, seemed nice as he pressed sweets upon me, and I could hardly refuse.

Eating sweets seemed to be a common practice in the buses. Our journey was irritating and anxious initially, with frequent police checkpoints on the Kenya side. A grim-faced copper or two would step up and peer inside the silenced bus. If they felt like it these sullen guardians of the law could search all the passengers, or even have the luggage brought down from the roof, a bag at a time. At each checkpoint, however, they received their baksheesh. Once I heard the driver instruct the conductor, “Give him a pair of pants”; this was done, and we went speeding on our way. It was only when we had crossed the border into Tanzania, Kilimanjaro rising ahead of us in the distance, that the mood inside relaxed, the passengers became chatty. We arrived in Moshi in the middle of the afternoon.

One of my fellow passengers was a young man called Pinto from Nairobi, a tour operator who had come from India only two years before. We found a hotel together and afterwards as we walked around were approached and befriended by a young Asian taxi driver called Dilip who took us to his home. The family was very modest, consisting of our friend, his young brother, and their parents. The father’s leg had been amputated after a car accident, and the older boy was the bread earner. I wondered why they took us in—did they expect something from us? Taxi fares? Perhaps they were lonely. Driving a taxi was not an Indian trade. Only later I realized that they must be from a so-called low caste. When the old man lost his “company” job following his accident, he had to give up the flat that went with it, and the family had to spend six months in the temple. After dinner and listening to incessant complaints from the old man about the state of the country (the refrigeration at the morgue was broken, for one thing, and there was a stench in the town) and the cost of living, Pinto and I went back to our hotel, which was above a noisy bar. It was the Hindu Navratri season, and during the night as the bar became quiet downstairs, I could hear strains from the singing at the temple.

Moshi and its sister town Arusha, an hour away, always had an English village feel to them, at least to those of us visiting from chaotic Dar. They were compact and neat, with tree-lined avenues and bungalows for houses; the weather was cool and the surrounding countryside lush and hilly. Moshi was the smaller town, with a set of streets named First Street, Second Street, etc., giving it added distinction. But the wonderful thing about Moshi was Kilimanjaro, seen from the main street looming majestically over the town, the smooth, round, snowy peak clear in the pristine morning air, then gradually donning a veil of cloud as the day wore on.

To me the great war does not evoke Flanders or Gallipoli, all vividly brought to life in novels and films, in the same way it does the windblown thorny semi-desert from Voi to Moshi under the mighty Kilimanjaro, and the road to Tanga. And there is the over-riding irony of it: the graves at Moshi, the anonymous monuments to the Africans and the Indians.

Elsewhere they talk incessantly about the weather; in Moshi they asked if there was a cloud cover yet on the mlima. This mighty mountain with its gentle contour remains the most awesome and yet heartwarming sight—even though I am not from the area—casting its benign gaze over the entire country. The story goes that originally—in the early days of colonization—it was part of British Kenya, but Queen Victoria presented it to her German cousin and the border was adjusted with a bend in order to accommodate the change. At the nation’s independence Brigadier Sarakikya of the Tanganyika Rifles planted the national flag on its peak, a momentous occasion symbolizing freedom, hope, ambition—an event that was commemorated on the highest-denomination postage stamp.

Our friend from the previous day, Dilip, took us around. There appeared to be a subculture of drifters and expats in Moshi—consisting of hotel managers, tour operators, and others—that he took pleasure in showing off. The Asian section of town consisted of rather pleasant-looking, flat-roofed bungalows and townhouses built in the early sixties. There was an older area that was eerily quiet, perhaps because there were no vendors or children in sight; the trees were ancient, and the bungalows staid, with high tiled or iron roofs. This would have been the old European area. Here we came upon a monument to “Hindu, Sikh, and Mohamedan” soldiers of WWI. Close by, in a tidy compound enclosed by a white picket fence, was a rather extensive war cemetery for the “British” soldiers, where I walked around while the others waited. The dead young men buried here wholesale in the neat rows of graves were all fully identified; many had been killed during the period March-May 1916. The cemetery was cared for by a British veterans’ organization.

Few people I met knew or cared that a protracted campaign of World War I—which changed so much of the world—had been fought in this region, that their town in Africa reposing at the foot of Kilimanjaro had a modern history that was fascinatingly connected to the larger events of the world; that that European war had also dramatically changed the course of this African nation.

*

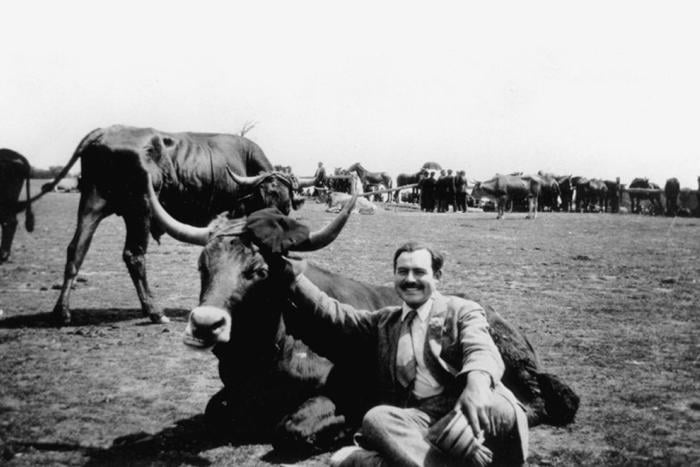

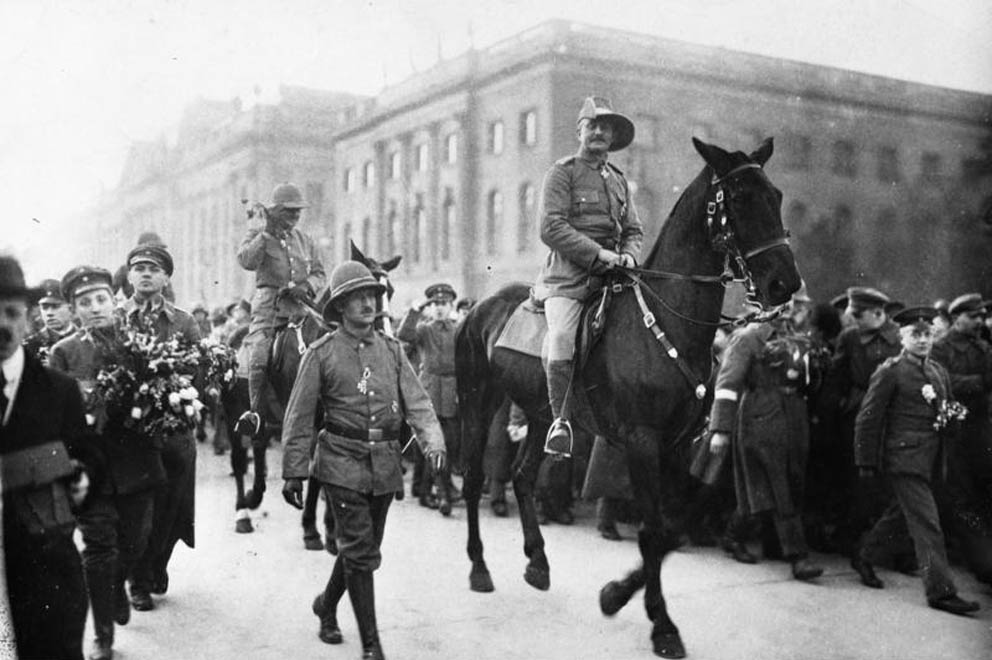

In November 1915, worried by reports of military setbacks from British East Africa (Kenya), the Committee of Imperial Defence in London recommended that the conquest of German East Africa (Tanganyika) take place as soon as possible. This turned out to mean immediately, and the man picked to lead the invasion across the Kenya-Tanganyika border was Lieut-General Jan Smuts of South Africa. Smuts, a diminutive man, was of Afrikaaner background, therefore arguably an African. In the Boer War (1899-1902) he had commanded guerrilla raids against the British. He had tussled with Gandhi. He was as tough as Lettow-Vorbeck, the German commander in Tanganyika.

Across the road from the church rose a site that made my heart race: old brick ruins crowning the top of a rise. We stopped so I could walk around. What remained of the original structure—a rectangular bunker—were the ruins of the outer walls, and in one corner an almost intact room with crenelated walls, a square opening on each of them, used presumably to fire down on the enemy. There was no roof, and the room was now used as a kitchen. The rest of the building had been patched up crudely with cement and brick and housed the church offices. Stones were scattered on the sides of the hill, debris that presumably had rolled away from the old structure. As we drove on, alerted, we noted occasional heaps of rubble that could very possibly—very hopefully—be signals from times past.

You have to go and see Lake Challa, the manager insisted, and the next morning we did just that.

The lake is inside a crater and invisible from the road, so that you have to walk up a hill to see it. And when you do so you come upon a sight of such breathless beauty it leaves you helpless. The sky blue, the leaves green, the dirt road an insignificant thin line. The lake below, crystal-clear blue, mysterious, deep; tiny ripples on the surface played by the wind like light fingers on a harp. You have no word to say, you walk away from the others. You say to yourself, This could be the site of Creation itself. And you want to hoard away this moment, so that years later you can say I was at Lake Challa. When the tourists had not arrived and only a privileged few knew about it.

You can, if you try, climb down to the water. We met two Masai youths who had done just that. We went half way down, but the climb was steep, and without a stick, as the youths advised us, it was not advisable. But at the top of the crater was a stone fortification, a wall, some nine feet high and twenty wide. This was where the South Africans had dislodged the Germans.

It takes some feat here—amidst this spellbinding natural beauty—to imagine tens of thousands of troops, animals, guns, motor vehicles. Dust, petrol fumes, animal odour in the air. They came, fought, and left, leaving only these stone clues behind, like men and beasts from another planet.

Lake Challa is fed by a stream from Kilimanjaro running underground. It runs, we were told, all the way to Lake Jipe, emerging once at the Njoro Springs. From the terrace of our hotel we could see a green belt apparently following that path.

Now here I was in Moshi a week later perusing the names of the war dead: J Watson of the Machine Gun Corps, and Private SHV Palmer of the 12th Regiment of the South African Infantry, and D Scott King of the 4th South African Horse, and W Dawson of the Calcutta Volunteers Battery, and many other young men of Smuts’s British army who died far away from home and were buried here in Moshi.