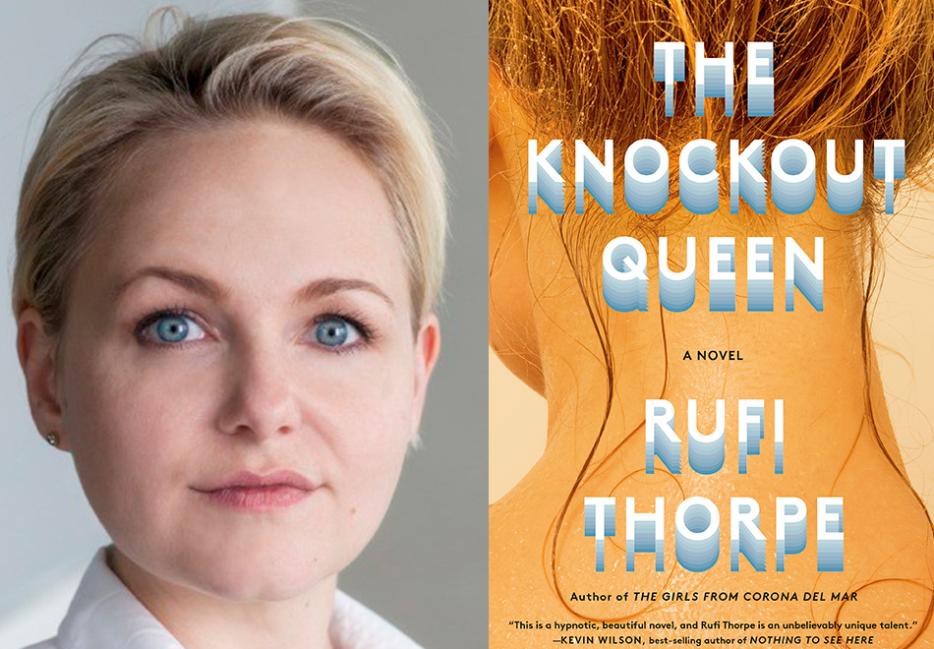

“You can know a lot about someone if you know who they were in high school,” Rufi Thorpe says. That’s one of the reasons her books tend to circle adolescence, she continues: because it’s the time when you are most authentically and unbearably your own self.

Thorpe’s first novel, The Girls from Corona del Mar, follows a pair of childhood best friends into adulthoods that neither of them could have predicted; it was long-listed for both the 2014 International Dylan Thomas Prize and 2014 Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Prize. Her second, Dear Fang, With Love, tracks a mostly-estranged father and his teenage daughter on a trip to Lithuania, his family’s homeland.

Now Thorpe has written The Knockout Queen (Knopf), about an intense, life-altering friendship between two outcasts stuck in the southern California suburbs. Michael and Bunny have been next-door neighbors for years, but they don’t start talking until one afternoon in the tenth grade, when she discovers him smoking cigarettes in her side-yard.

“One thing Bunny and I had in common,” Michael explains, “was an unusual lack of adult supervision.” Their relationship becomes something both can depend on in the absence of parental involvement and care. Bunny’s father is a successful real-estate agent and a serious alcoholic; Michael is living with his aunt and hiding the fact that he’s gay from his family as best he can.

The Knockout Queen is about sex and violence and shame, and how utterly, impossibly commonplace they are. The book outlines how the secrets we keep begin to keep us, or, as Michael puts it, describing his relationships with men he meets on Craigslist, the “lives strange to me that turned my life strange.”

Thorpe and I spoke by phone several weeks into our respective Coronavirus isolations, on a beautiful southern California day when neither of us could go outside. Her children interrupted occasionally to ask for dispute mediation, or help with the iPad. Their contributions to the conversation aren’t included below, but it feels right to note that, as Thorpe is a working mother, of course they were part of her day.

Zan Romanoff: Four years ago, you wrote an essay called "Mother, Writer, Monster, Maid" for Vela that got a lot of traction. You've said since then that you sometimes think about writing a follow-up about being the parent of slightly older kids, and how that’s a different experience from when they’re very young and everything feels acutely terrible. Is that something you’re still interested in, or working on?

Rufi Thorpe: I sort of was trying to write it this go-round of publicity, but I wasn't able to produce anything satisfactory.

Part of the roadblock to trying to write a similar thing about parenting older kids is the recognition that, when you're still in the baby part of it, nothing can help you. What happens is not that you figure out how to do it; it's that the experience hardens you and matures you, and then all of a sudden in this new honed form you can just slice through it, and it's like butter. It's not hard anymore. But you can't do that to yourself voluntarily. There's no mental position you can find that will allow you to skip that part. It just sucks.

I will say, as someone without kids, I do wish there was a little more writing about the easier or more manageable parts of it— because it feels sometimes like most of the pieces I read are from people who are in the worst of it, and then it’s hard not to conclude that the consensus from women writers is: if you have kids it will completely ruin your life.

But I can also imagine that, like, if that’s your reality all day, of course you want your work to take you somewhere else. To be writing about other things.

I know some writers decide to write a book because they think such a book will sell, and is a compelling market opportunity. I have never been able to do that, because to me the compulsion to spend thousands and thousands of hours thinking and then writing about imaginary people… money, especially uncertain, speculative money, is not enough. I have to be really, really interested in whatever it's about. And you're not able to control what you're interested in very well.

You wrote a book between your second novel, Dear Fang, With Love, and The Knockout Queen that you didn’t end up selling. Tell me about that experience, and how it kind of led you to The Knockout Queen.

Oh yeah, my big failure!

I was in a really dark period. The Girls from Corona del Mar had gotten published, and it all felt really magical. I got pregnant with my second baby and I had this really positive birth experience that was really different than my first birth. And then we decided to move back to California, and I was so happy to be close to friends and family.

And then my husband got a job where he had to work really long hours, and he was driving 100 miles a day in LA traffic. Then my youngest baby got sick with RSV and was in the hospital for five days. I don't think he was in danger of dying; however, it was still terrifying.

So, I had a period where I felt like I was being consumed by the children, and I was never gonna write again.

Then we hired my husband's cousin to come live with us. She would watch the baby for two hours a day, and in these hours, I wrote this book.

I think there was just too much pressure on it. I was writing it more hoping it was good than trying to say something. I just was exhausted. It wasn't good.

I don't think the book is unsalvageable, but once I finished it and understood what was wrong with it, I had no idea how to fix it. And no interest in fixing it! So I was like, maybe I'll come back to it, but now I want to write something that's just like... the way I phrased it to myself was, “fun.” I wanted it to be for me. I wanted to write something that was what I wanted to write, instead of what I thought anyone else wanted me to write. There was a weird defiance to the energy with which I started the book. I was feeling very, fuck everybody!

I had written a book titled Bunny Lampert like ten years ago. It didn't have this plot, but it was about Bunny Lampert.

I've been thinking about this character for years and years and years, so returning to her felt kind of like getting in touch with that original high school part of myself, that part of yourself that you learn to be embarrassed of, and then later when you're much older, you learn you never should have been embarrassed of. I think in some sense that's what allowed the book to be as direct and honest as it is. It's a very me book. It's not posing as anything. It's very frank and genuine.

It definitely has a fuck you energy—but in a delightful way, not an angry way. It feels sometimes like authors now are very careful around our books in this too-cautious way, like, can anyone, anywhere, for any reason, get mad at me about this? And I loved that there was stuff in there where it's palpable that you're not thinking about what anyone else is going to think, and just getting weird.

Along those lines, I am curious about your thought process around deciding to narrate the book from the perspective of a gay man.

I thought deeply about it. We've all been watching through various think-pieces of better and worse quality about cultural appropriation and how that affects fiction, and I have all sorts of conflicted feelings. Growing up as a woman reading literature and watching men write female consciousness, the idea that I wouldn't be allowed to do that to someone else, when all of literature was doing it to me seemed like, well then, what are we doing?

I thought there was this understanding that Anna Karenina is not a woman; she's a fantasy of Tolstoy's. And Michael is not a young gay man; he’s a fantasy of mine. You will learn a lot more about me than you will learn about young gay men by reading it.

When I got the idea for Michael it was very much like, he just appeared, and had a super strong voice and a specific backstory right from the beginning. It was one of those times when you feel like the character's writing itself.

Now, in my experience, that's because the character is a deeply repressed aspect of yourself. So soon enough, he started to narrate things from my own life, things I was really uncomfortable with.

Throughout my 20s, I would meet women from the internet to have sex with them, because I couldn't deal with the fact that I was bi. I had this whole weird doublethink world where I just liked to do that because it was fun, and really, I was straight.

The very same thing that made me write Michael is also what gives me no right to write about him. I've been a horrible member of the gay community—I never officially came out! I have not contributed to that community. I'm just a fucked up person, writing about how I'm fucked up. How do you say whether that kind of material is authentic?

The book is about the rebelliousness of the body—the way the body can want something almost against your will. The whole book is about that, so it makes sense that I found a way to hook it to these experiences that I had. It makes sense that I brought them up.

But why not, once I realized that, make the character female, so that it was a true direct autobiographical thing? And the answer's really simple. It's that I love writing as a man, because then I don't have to deal with all the bullshit. I didn't want to deal with Michael and "is his behavior slutty?" If I had a female character doing that, there would be all of this cultural baggage I'd have to deal with.

Those kinds of workmanlike craftsmanship concerns, they feel so petty to bring up when you're trying to talk about the real big true sins of cultural appropriation, the ways that it can be damaging to people, the ways that it can be hurtful— and yet, every fiction writer is making very workmanlike, craftsman decisions, where they're thinking about characters' gender not based on, can I authentically do this, but like, what works better for my plot?

Is a craftsmanly excuse good enough? I don't know.

There's a lot of physical violence in this novel. It feels like you're working to situate violence in the ordinary—not in a David Lynch, “ahh this is so surreal” way, but just like, horrible things are happening all around us, often in the most mundane ways possible.

I was a gigantic child. I've been this height since I was 10 years old, so I had this belief that I was going to be a giantess. In part because I didn't know my dad, it felt like maybe it was possible. And then I just never grew again, but I've always been densely muscled and really strong. So I wasn't tall—so what? I still felt really physically powerful.

And then I was in a relationship that was physically abusive. It wasn't just getting decked a bunch; it was a lot more physically grappling, or being thrown, or struggling to get away. The realization of how much stronger he was, and how truly helpless I was, was like, a thing that I couldn't get over.

So the dream of a woman that is physically powerful—the dream of a woman that could pick up a man and throw him—is very compelling. It's a wish-fulfillment. I think Bunny comes from those set of fantasies, inspired both by cultural narratives and my own autobiographical reasons.

There's a line in there where Michael says, "The people I have the most sympathy for were almost never the ones anyone else felt sympathy for." And that feels like exactly the project of the book—to take characters who, when you describe them as types, sound unsympathetic, and be like, these are the people you're going to spend time with, and come to care about.

My instinct to do that is one of my core—like, you can't help it if Ray Lampert's your dad! You gotta deal with it one way or the other. He is shitty, and there's good things about him. In some ways he's a great dad; in other ways he's a terrible dad. People are really flawed. And you have to deal with them anyway.

Yeah. I also love the way you write about class and aesthetics. A lot of the houses in Knockout Queen are kind of suburban and unremarkable—not like, luxe and thrilling, but also not poverty porn. Just the house you buy because you need a house, and this is the amount of money you have, so that’s that.

I feel like you’re really good at writing places that feel like places, instead of like, Backdrops for a Novel.

I am of a family that's maybe what would be called the fallen aristocracy. We still have the carpets; we don't have anything else. I have lived in-between classes in a lot of ways. My background is still one of unfathomable privilege; I'm just saying, we've never owned a nice car or something.

I think there is a tendency to present attractive, opulent settings without any nuance or suspicion of them, and they're almost just the standard backdrop settings of the people who can afford to have the kinds of problems that you want to write about. There’s not that many novels written about trying to figure out how to pay your rent.

I also love houses—maybe that's part of it. I'm addicted to looking at house listings, and I'm very crafty.

I wonder if that's a Californian thing? I don’t care that much about real estate in my real life, but in my writing I'm obsessed with houses, and what's going on in all of them.

So much of the history of the novel is about the development of these metropolitan centers, and this Balzacian sense that the city is an entire world, and every kind of person is living there—that you could somehow peek into each of their lives. I think that is very much the part of the novel that I'm drawn to and fell in love with. I'm a nosy, nosy bitch.

I think that's every novelist. You have to be!

You’re eavesdropping, asking people invasive questions about their moms. How does that make you feel? You're like a therapist with no morals, and no obligation to help.

That is damning, and true.

You said earlier that this book is about the ways that your body betrays you. One of the notes that I took while reading just says SHAME, in all capitals. So I'd love it if you could talk more about how that force functions in the book.

I think that shame comes with the territory of all the other things, ‘cause I think that there's a lot of doublethink, especially around violence. Is it a natural primate-y kind of thing that we do sometimes, or is it evil?

We do a lot of similar doublethink around sex. There's every fucked up part of the thinking life of modernity in those questions. It's all gotten just jammed together into a bunch of conflicted feelings about our most basic activities. And so, anytime you're gonna talk about sex or violence, you're going to talk about shame, because none of us can figure out how we're supposed to feel about sex or violence.

I also think that shame is just interesting. Because sometimes I'm not ashamed of the things that I should be ashamed of, but I'm ashamed of some things so intensely that I know they're occupying—it's like a storage unit you can't get rid of. You know you don't need all that stuff, but you can't let go of it. I know there are vast interior spaces that are occupied by holding onto shame for things that I can't go back and undo.

People say "forgive yourself," and you're like, all right. How? Tell me, physically, what should I do?

I have always been puzzled by the phrases "love yourself" and "forgive yourself," because I'm like, all right. Literally, I have had to—the love yourself one, I've broken down into steps. But forgiving yourself I think is a lot harder, because sometimes you just… don't. It's really hard to forgive yourself if you don't.

As I was reading through the book, I was thinking about how the characters do all kinds of things, some of them good, some of them bad. But it fees like the true warping force, the thing that really actually fucks them up, is shame—is that no one feels like they're allowed to be the person that they are.

I think what I'm circling around here is that the book is, in so many ways, about how we are just at the mercy of each other. We want to be loved and accepted and cared for so badly, and no matter how much we want it for ourselves, we so often do not give it to other people! It's heartbreaking!

There's also the problem of how to contain the psychos. What do you do with Ray Lampert? That's the problem with prison, is that it's such a clumsy and stupid solution to what is a much bigger problem, which is: what do you do when individuals in the group begin harming the group?

Prison is this weird form of shunning where it's like, you have to go live alone in this box with the other bad boys. It doesn't work very well; it is completely metaphysically without meaning, and it actually fucks everybody up more. Prison doesn't help anything get any better.

But people are really at a loss as to how we could do anything else. We don't have another framework, even for imagining what else we could do. Or even just on a personal level, in your life. What do you do with family members who are toxically fucked up? What do you do when your kid is a drug addict or an alcoholic and you don't want to keep enabling them? Where do you draw those lines? How do you deal with people who are starting to hurt other people?

Yeah, and that feels related to one of the big questions that sort of haunts your work, which is: who gets out? Who survives these messed-up childhoods and gets to go on and thrive? It’s a big question between Mia and Lorrie Ann in Girls from Corona del Mar, and it recurs again in Knockout Queen.

For Mia and Lorrie Ann, Lorrie Ann is being inexplicably punished. She is actively good, and Mia can't figure out why life is punishing her. In the case of Bunny and Michael, she is being punished for something she did. And he cannot decide if she deserves the punishment or not. If she's not being punished enough, then he starts to think that she should be punished more. Then when she's being punished, he thinks she shouldn't be and it's unfair and there's been a miscarriage of justice. He's not really sure. And then she is made strange to him through her punishment.

You can tell what interests me! They're very similar books in lots of ways. They're both about friendship, and they're both about trying to reconcile who you were in high school with who you are as an adult.

There's nothing more embarrassing than writing more than one book, because it becomes apparent that you only have like, a limited set of obsessions.

There's a very wonderful book—The Forest for the Trees, by Betsy Lerner. It's a book about writing from an editor and agent's perspective, the lion tamer's tale if you will—a lion tamer's book about lions. She's like, “Listen, I'll tell you exactly what kind of creatures you are.”

It's very comforting. She's like, “You don't get to choose what your material is. You get the things that obsess you. There's going to be three or four if you're lucky; probably just one or two. And then you're gonna write the same book over and over again, exploring those themes. Some of the books will be good, and some of them won't be. That's what you're gonna do for the rest of your life. Giddyup.” I was like, Oh my god, that's such a relief!

There's this moment at the end of the book where Michael says, of Bunny, "I wanted her tragedy to belong to me." And that felt sort of like what authors are always doing—putting our characters through horrible things for our own selfish reasons, or like, telling other people’s stories as a way of telling our own.

I'm a reckless and irresponsible god to my characters. I don't really worry about their anguish.

I take care to love them. I feel like that's my job, is to see them and record all that is beautiful and awful about them. I feel like it's my job to put them into the most extreme positions possible, so that they can fully reveal themselves.

Yeah, totally. I guess this felt, to me, related to the question of, what right do we have to tell the stories of people from groups we aren’t a part of? In this case it's just, what right do we have to write at all?

The answer is: we don't! But we do it anyway.

There's a great quote by Zadie Smith. She's talking about how women have felt really connected to these fake, man-made women in literature, and that it's perverse but it's the kind of thing that's possible in fiction. It's morally irresponsible, but that fiction is, at root, irresponsible. It's not able to be morally accountable in that way; it's not interested in it. That's not what it's about.

But there's also ways in which fiction is enriching. If I hadn't found ways of feeling seen and understood by books, I think I probably would have committed suicide. That was how I figured out that there were other people that I could commune with. I wasn't good at understanding how to do it with other people when I was a baby monster. So I do still have this devotion to it as this transcendent medium that allows minds to be in communion with one another throughout space and time.