In high school, I was flipping through one of the last ever issues of Jane magazine (shine on, you crazy cubic zirconias), in which senior editor Joshua Lyon had this to say about Katherine Dunn’s 1989 novel, Geek Love: “If you don’t fall in love with the albino hunchback dwarf by the time she murders her daughter’s evil benefactor, then you’re a cold-hearted bitch.”11It seems almost necessary to begin a tribute to an author with an origin story of how one first came to discover their work, so I’ll make this as quick as I can. I was newly seventeen, trying to find to find books that were viewed as smart and literary and grownup but still spoke to what felt like, at the time, a very specific kind of alienation, experienced only by me and every other teenage girl on the planet. I had done your requisite Bell Jars and Catcher in the Ryes, spent weekends in high school at the used bookstore downtown, picking up works by authors with whom I was only familiar because I had read their other books in English class—Orwell and Fitzgerald and Huxley and other books so predictable that were favoured by kids who knew they liked to read, but had not yet developed any tastes of their own.22I’m getting to Dunn, I swear. The difference between writing an essay about an author and writing an essay about an author hours after learning of said author’s death is that I am compelled to start every line with “MY FEEEEEEELINGS.”

Learning that Katherine Dunn passed away on May 11th at the age of 70 because of complications from lung cancer was bracing. Like recently departed outliers Prince and David Bowie, she seemed larger than life, immortal, but unlike them it wasn’t because she was a prolific, constant presence; she was the opposite, a quiet force associated with one major work published almost three decades ago who had a devoted readership antsily waiting for a follow up.33She had allegedly been working on another novel since Geek Love’s completion called The Cut Man that, according to Caitlin Roper’s excellent profile of Dunn published in Wired, she was still working on in 2014. The fans were restless but patient. Dunn could take as long as she needed, was the mood. She wasn’t going anywhere.Dunn had written several other novels and has had a steady writing career for the past few decades, but unless you are one of six people who have actually managed to track down and read Attic (1970) or Trunk (1971), or a sports aficionado who paid attention to her boxing reporting (which surely has a lot of overlap with literary nerds), your relationship with her centers around this specific book.

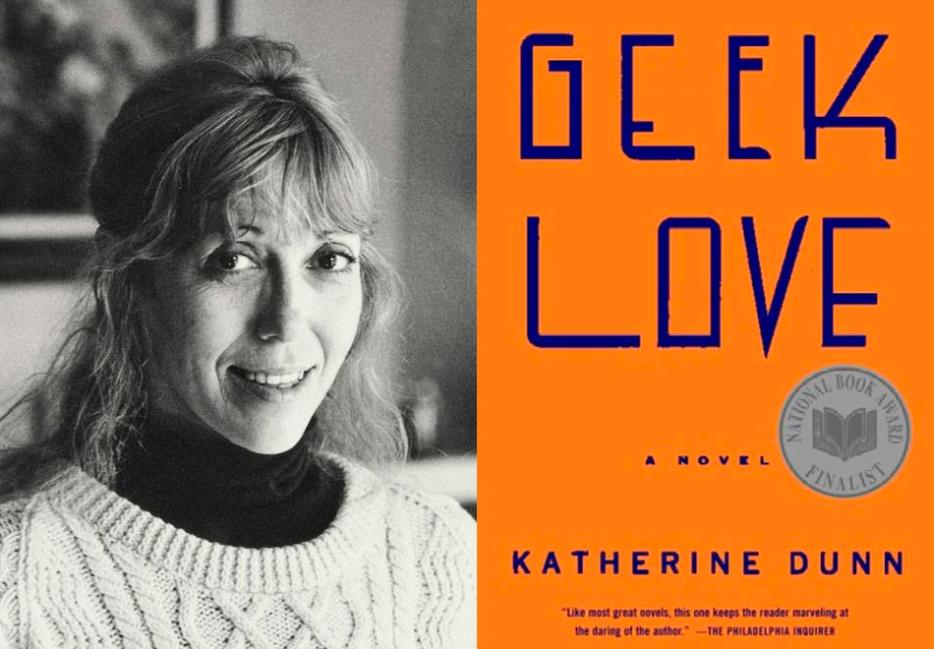

I didn’t find a copy of Geek Love at a used bookstore until later, after I had already finished high school. Its neon orange and navy cover designed by Chip Kidd was a stark contrast to the somber shades of black in which my usual aspirationally serious Penguin Classics came decked. The synopsis can sound charmed and whimsical—it’s a story about family and being true to yourself, set against the fun and colourful backdrop of a travelling carnival, hurrah! Let down your guards and join the party!

If you haven’t read the book yet (in which case, dude, get on that), it goes like this: Al Binewski and his wife Crystal Lil run a carnival together, and are shrewd businesspeople when it comes to the voyeuristic tendencies of the American public. They plan to open a freak show to rival all others, and so during Crystal Lil’s pregnancies she consumes poisons and chemicals. Most of the fetuses don’t make it to childbirth; those that do become the main attraction. There’s Arturo, with flippers for hands and feet; conjoined twins Electra and Iphigenia; the aforementioned hunchbacked albino dwarf Olympia (“Oly”) who narrates the story; and baby Fortunato, whose peculiarities take the longest to surface.

As they become older, the children grow resentful, not of their parents who bore them into this life but at the rest of the world, those who regard the children’s disabilities with revulsion and hatred only to later empty their pockets for admission under the bright striped tents. Arty, the eldest, learns to harness the hypocrisy and shallow longings of the American public, fashioning himself into a kind of cult leader with masses of followers falling at his every whim. The results, like so much of the book, are stomach churning, uncanny, and engrossing. Once you pay the cover price, you can’t look away.

“‘There are the those whose own vulgar normality is so apparent and stultifying that they strive to escape it,’” he says. “‘They affect flamboyant behaviour and claim originality according to the fashionable eccentricities of their time. They claim brains or talent or indifference to mores in desperate attempts to deny their own mediocrity.’”

Of course, this passage could absolutely and one hundred percent describe me. Were I a character in Dunn’s world, I would be a nameless extra or one of Arty’s desperate followers, certainly not one of the special few around which the story orbited. The same could be said for most readers. The power of Geek Love is that those reading it, with their thrift store dresses and dyed hair, claiming originality according to the fashionable eccentricities of their time (ahem), can find a kinship in Oly’s guileless narration. Her abnormal upbringing, her unique challenges, her at times more-than-borderline-incestuous admiration for her brother were relayed so intimately, she became a stand-in for a kind of typical adolescent (and later, adult) alienation.

Geek Love is by no means an obscure book; it was published by Random House and was a finalist for the National Book Award. (It lost to John Casey’s Spartina.) Yet it has a reputation for achieving a cult-like status, for the rabid ways in which fans approach it, engage with it, consume it. It’s become a cultural shorthand a very specific type of contemporary weirdo, a person who romanticizes eccentricity for better or for worse. There are a lot of other pop culture artifacts that could fit this description, but Geek Love is so singular because it’s, well, good. Modern day Tim Burton would cut off his limbs to produce something so magically unsettling.

Dunn created something special with her novel, a story that feels endless in its increasingly disturbing plot points yet ends way too soon, that casts you, the reader, as antagonist while causing you to identify with the protagonists, that dazzles and shimmers and horrifies, that is widely influential yet incapable of being matched. Rest in peace, Katherine Dunn.