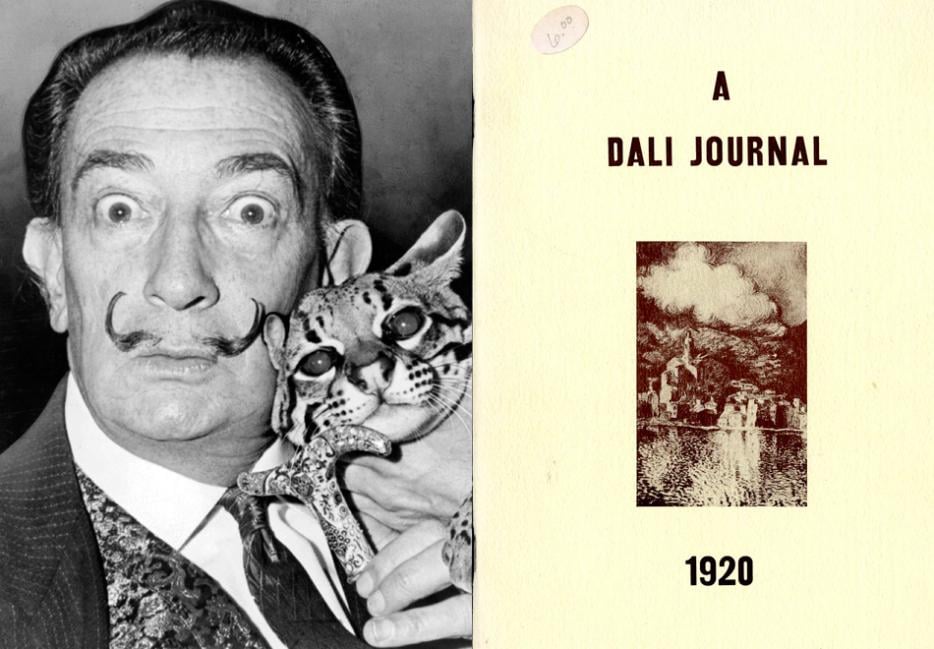

In his later years and posthumously, Salvador Dalí has become synonymous with overexposure and commercialization. Google him and see his stilt-legged elephants on a shower curtain, Mae West lip-shaped perfume bottles, and his own signature bug-eyed, waxed-moustached face printed large on a psychedelic T-shirt between the words I DON’T DO DRUGS and I AM DRUGS. Anyone who’s stumbled past the open door of a college dorm room recognizes Dalí’s masterworks and knows that a soft clock is the perfect metaphor for life inside the room: time slipping away unnoticed, the warp of memory, and meaningless invention.

But Dalí was an artist of far-ranging talents who worked in almost every medium, including fashion, film, illustration, advertising, architecture, and sculpture. He was a young prodigy, doing paid illustration work for local merchants when he was just 11, and entering, when he was 18, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid, where he befriended Luis Buñuel, Federico García Lorca, Eugenio Montes, and many others who would go on to become widely known artists and intellectuals. He booked his first solo show less than three years later at the Galeries Dalmau, in Barcelona. Soon after, his work showed in America for the first time: a painting he made while attending school in Madrid called Basket of Bread.

Despite this range of talents, Dalí first considered himself a writer. He published four books in his lifetime, including a novel, Hidden Faces, and the alternately lauded and criticized surreal autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, which George Orwell called “a direct, unmistakable assault on sanity and decency,” and also authored several more books that were not published until after his death. He was a frequent contributor to magazines and art and literary journals, beginning when he was still in drawing school with Studium, a journal he wrote for and edited with his classmates, and continuing throughout his life, publishing poetry, aesthetic manifestos, reviews, and essays in L’Amic de les Arts, La Publicitat, Minotaure, and elsewhere, and lending illustrations to many books and articles. He was also a voracious reader, owning an estimated 4,500 volumes at the time of his death.

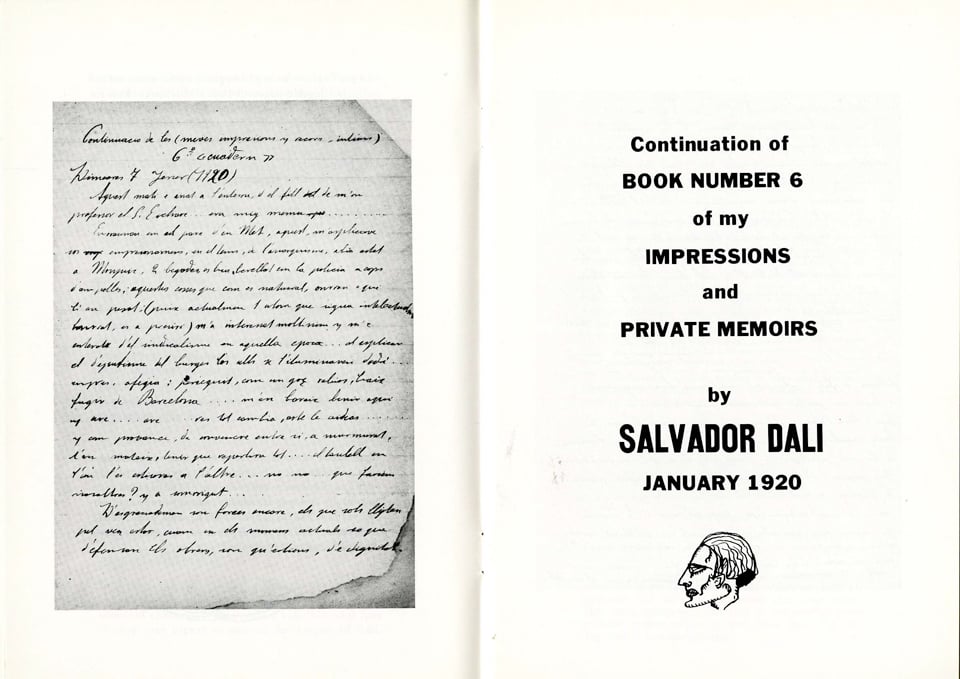

In 1964, Dalí published the first edition of Diary of a Genius (1952–1963) with Éditions de la Table Ronde, of France. It has since been translated into Spanish and English, with the first English edition published in 1965, by Doubleday. But long before Diary of a Genius, Dalí kept a childhood diary. Between November 1919 and December 1920, in Figueres, Dalí filled an estimated 11 notebooks with what he called his “impressions and private memoirs.” Seven of them were published together in a 1994 edition by Dalí scholar Félix Fanès for the Fundación Gala-Salvador Dalí, the foundation that manages the artist’s works, under the title Un Diari 1919-1920, and were later translated into French for Anatolia (Le Rocher). But no English translation yet exists for the diary, save for a single fragment.

In October 1960, Reynolds Morse, a businessman and philanthropist from Cleveland, purchased a notebook from Dalí’s 1919-1920 diary from a Parisian antiquarian bookseller named Jean Hughes. According to Hughes, the notebook had been left behind in the poet Paul Eluard’s home when Gala Eluard, later Gala Dalí, left Eluard for Dalí in 1929. Hughes had purchased the notebook at auction in Bern, Switzerland, two years prior. Morse went on to have it translated into English and, with Dalí’s permission, edited and printed it privately in a very limited edition for the Reynolds Morse Foundation, in 1962. Dalí’s only stipulation was that it never be made for sale.

The book itself is lovely. It’s saddle-stitched with a pale yellow, unfinished paper cover and semi-gloss interior pages; with black and white illustrations throughout, and occasional photographs; and a further collection of photographs and reproductions of handwritten pages at the back. It is organized not only by date, but also by manuscript page, and includes an introduction by Morse, and Morse’s elaborative notes at the back, as well as the translator’s. Joaquim Cortada I. Perez was a translator with whom Morse worked on at least two other books: another on Dalí, and one on the writer M. P. Shiel. The entirety of the A Dali Journal book is only 64 pages.

By the time A Dali Journal was published, Dalí and Morse had been friends for two decades. Dalí made the first two sales of his paintings to Reynolds and Eleanor Morse in 1942: Daddy Longlegs of the Evening—Hope! and The Archeological Reminiscence of Millet’s ‘Angelus’. Over a lifetime of friendship with Dalí and Gala, the Morses would acquire the most comprehensive collection of Dalí’s works in the world. In 1971, they opened the first Dalí Museum in the U.S., in Cleveland, and later moved it to the waterfront of St. Petersburg, Florida, noting that St. Petersburg was the ideal site, as it reminded them of Cadaqués, the Spanish town on the Mediterranean Sea where Dalí grew up and began to paint.

In Dali: A Life in Books, Ricard Mas observes of the 1919–1920 journals, “They are written in a not very correct Catalan, more in line with phonetics than with syntax,” and include, as in all of Dalí’s writing, frequent misspellings, “though in view of the way Dalí wrote the other languages he knew to some extent (Castilian, French, and English), we can not rule out some type of dyslexia or dysgraphia.” Nonetheless, Dalí’s writing here is mature, belying someone deeply immersed in literature and with an ear for sound:

We got off at the Llansa station. A thick fog of smoke was rolling on the roof which was covered with moss. The morning dew moistened the fields and neat clean droplets of moisture were slipping from the red and white petals of the blossoming almond trees. They were raising their branches in blossom against the clean blue color of the pure and cloudless sky.

His prose is romantic, lyrical—rich in sensory description, to the point of being, even years before his first encounter with the movement, surreal. Take, as a minor example, this later passage, from the same entry, in which Dalí goes to a picnic—with a good deal of expansion, these lines could transform into a complete short story, or the opening lines of a novel (the ellipses are Morse’s, not mine):

We went to the Aleche’s, he had been charged with the responsibility of having the food for the picnic meal ready. My father was of the opinion that he had caught too few sea urchins … so we went to the sea … the scent of shellfish flooded my lungs … the sea was blue and motionless … we bought more sea urchins … we picked out the spot to have lunch.

Dalí begins here with a straightforward situation: they’re at a picnic, and it was someone’s responsibility to have prepared lunch. A conflict arises: in his father’s opinion, there aren’t enough sea urchins for the lunch (it’s important to note here that Dalí and his father shared this favorite food). As a solution, someone proposes they go to the seashore. Suddenly, a hallucinogenic rush of sensory information, and dramatic language: scent of shellfish, a flooding of the lungs, juxtaposing the blue of the sea, the stillness of the water. And as quickly, we’re no longer in the sea; we’re simply buying more sea urchins. We’re sitting down to eat them.

Dali writes like he paints and paints like he writes. There’s imbalance within compositional balance; he is lyrical in his natural settings, and deeply symbolic—among other images, sea urchins will appear in Dalí’s work time and time again in what Morse terms the “Dalinian Continuity,” including in The Madonna of Port Lligat, and The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus. As well, the Catalonian coast figures largely in The Hallucinogenic Toreador, The Persistence of Memory, and many others of Dalí’s masterworks. Dalí’s earliest paintings are little more than Impressionistic experiments with Catalonian coastal landscapes.

In his introduction to the journal, Morse emphasizes the rarity of the expression “by a Catalonian about Catalonian events.” Much of A Dali Journal documents, with astounding clarity, Dalí’s witness to the unrest of that year among the corrupt central government, labor unions, and violent anarchist forces—early precursors to the Spanish Civil War, which are fascinating and upsetting to him. At this point in the journal, the illustrations by Dalí that Morse has included have become morbid. An old man hangs from a noose with his tongue lolling out. On the facing page, a warrior with sword in hand extends the severed head of a long-haired man toward the viewer.

Dalí’s acute observations of daily shifts in Spain’s politics are likely a product of his family’s dedication to and deep feelings about current events, a characteristic they shared with all Catalonians. What may be interesting to those who are only familiar with Dalí’s later favoritism of Francisco Franco’s regime, and even later apolitical—indeed capitalistic—attitude, are Dalí’s younger anarchist and communist leanings. He displays a deep distrust of the government and a belief in the liberation of the workers fighting against it. He writes: “Unfortunately a large number of men still are only interested in fighting for their own interest while the workers are now fighting for questions of dignity.”

It is in these notebooks, though not in this fragment, that Dalí announces his plan to move to Madrid to attend art school. Nonetheless, we see in A Dali Journal the glimmerings of Dalí’s desire to commit himself to art. In one passage, he meets an old, enlightened man named Mr. Verges, and recounts their conversation:

Verges said ‘I am going to Paris … it is necessary to go away from this routine and monotonous life, it is necessary to run away from this stupid mundane life … I will work in any job, even if I have to work as a manual laborer, I shall send the money I earn to my grandmother … and I shall live within an artistic environment which I am missing here.’ And his eyes were shining with happiness and his heart was longing for his desired future. We spoke for a long time about art and the spirit; and when saying goodbye, I grasped his thin, bony hand.

In a letter to his uncle, Dalí reflects on his painting practice—“Every day, I realize more and more how difficult art is … but also every day I rejoice and like it”—and admits that he pays no attention to drawing—“I do completely without it”—when making his paintings, and instead devotes all of his efforts to color and feeling. Here we see a glimpse of typical teenage rebellion in Dali’s opinion that it is unnecessary to devote himself to technique—“[it] does not require any serious study or great effort.” It’s delightful and surprising, considering his later distinguished mastery of technique.

Morse says, “By some miracle, these ephemeral papers managed to survive many vicissitudes. The first was Dali’s flight from Spain at the beginning of the Civil War. The second was the painter’s last minute escape from the invading Nazis. And perhaps the most remarkable, the subsequent lootings of his Paris apartment.” Yes, it is a privilege to find this window into the young master’s mind against so many odds, and to find so much here that is at once extraordinary and relatable. It could only be enhanced by the English translation of the rest of Diari’s volumes. Translators, do you hear me?

(With special thanks to Salvador Dalí Museum librarian Shaina Buckles for her diligent assistance.)

Paper Trail is a monthly column exploring the relationship between artists and their journals.