What’s in a name? Judging by the pitiful state of neglect the legacy of Amor De Cosmos is in, an awful lot. If he’d retained his birth name, William Alexander Smith, perhaps he’d be remembered for the central role he played in uniting the colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia and bringing them into Confederation in 1871, all while fighting for the right to democratic representation and responsible government. Instead, he’s a footnote, resigned to the historical record’s curiosity cabinet because of his name and his host of eccentricities—a pronounced fear of machines and an abiding distrust of electricity among them—that are magnified because of it. But with Stephen Harper’s Conservative government pouring millions of dollars into a public relations campaign designed to elevate the importance of the war of 1812, launching a review of what gets taught in Canadian history classes and otherwise mucking around with our country’s historical record, it appears the books are open, so to speak. And if there’s anyone who deserves to have his place in Canadian history re-assessed, it’s Amor De Cosmos.

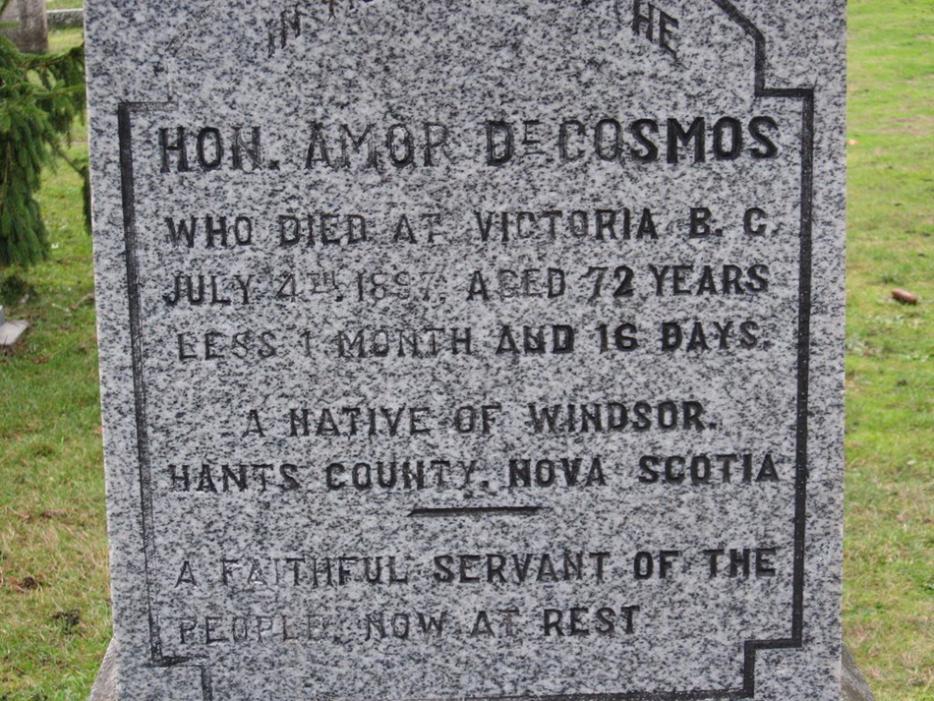

De Cosmos was born in Windsor, Nova Scotia, and came of age in Halifax, but his story begins in earnest when he went west in 1852 to find his fortune, first to Iowa and then a year later to Placerville, California. During the voyage across the continent, he and his convoy apparently fought off numerous attacks by marauding Indians before wintering in Salt Lake City with Mormon leader Brigham Young, where, depending on which rumour you believe, he busied himself with trading, fending off Young’s attempts to marry him into the community, or stealing some of the church’s most sacred writings. In any event, he left the next spring, and in his haste to get to California he pressed on ahead of his traveling companions, a decision that nearly cost him his life as he suffered through various degrees of starvation, hunger, thirst and alkali poisoning in the Nevada desert before making it to Placerville.

De Cosmos was born in Windsor, Nova Scotia, and came of age in Halifax, but his story begins in earnest when he went west in 1852 to find his fortune, first to Iowa and then a year later to Placerville, California. During the voyage across the continent, he and his convoy apparently fought off numerous attacks by marauding Indians before wintering in Salt Lake City with Mormon leader Brigham Young, where, depending on which rumour you believe, he busied himself with trading, fending off Young’s attempts to marry him into the community, or stealing some of the church’s most sacred writings. In any event, he left the next spring, and in his haste to get to California he pressed on ahead of his traveling companions, a decision that nearly cost him his life as he suffered through various degrees of starvation, hunger, thirst and alkali poisoning in the Nevada desert before making it to Placerville.

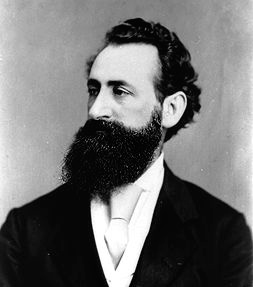

When he got there, he set up a daguerreotype photography studio, taking portraits of prospectors and merchants and, according to legend, shooting some of the earliest forms of smut. And while he eventually busied himself with the comparatively unexciting business of photographing gold claims—as historian George Woodcock wrote in his 1975 biography of De Cosmos, “He had the good sense to realize that the most certain way of prospering in a gold-rush lay not in working the mines, but in providing services that the miners could not do without”—controversy and intrigue still surrounded him. He was, for example, rumoured to be involved with, or even one of the leaders of, the Vigilantes, a group that administered a rough form of justice (paid, of course) in the California gold fields. Some have even suggested his decision to change his name at the age of 28 was an attempt to bury that relationship in the past.

But, as Woodcock noted, the historical record from the period reveals no connection whatsoever between De Cosmos and the Vigilantes, nor any attempt by the former to sever his association with the latter. It may have simply been the first high-profile manifestation of the eccentricities for which he would become notorious later in his life. Or, as the late historian Abe Arnold and others have suggested, it may also have been driven by more pragmatic concerns: there were so many William Alexander Smiths at the time that he found it difficult to get his mail. In any event, as Arnold told Peter Gzowski during a 1977 interview, the name he chose was not without meaning or intent. “He chose his new name because it was unusual and its meaning told of what he loved the most: love of order, beauty, the world, the universe. And so he came to be known as Amor de Cosmos, lover of the world.”

In the spring of 1858, with word that gold had been discovered in both the Fraser and Thompson Valleys, 30,000 men poured into the sparsely populated fur-trading outpost of Victoria. De Cosmos was among the horde and liked what he saw—so much so, in fact, that he returned to El Dorado, wrapped up his affairs there and returned to Victoria in June. By December, he’d started an independent newspaper called the British Colonist.11Today, it’s known as the Victoria Times-Colonist.

He immediately went to work attacking James Douglas, the governor of the colony of Vancouver Island and, in De Cosmos’s view, a Hudson’s Bay Company stooge. By spring of 1859, Douglas had grown so tired of the constant attacks that he invoked an old statute (one that had already passed in obsolescence in Great Britain and would soon be repealed there) that required newspaper publishers to post a bond of £800. De Cosmos probably could have posted the bond himself, but instead used the moment to spark the cause of political reform in the colony. The paper suspended publication on March 31st, and by April 4th his supporters had gathered in the Assembly Hall in what was, at that time, the largest public meeting in Victoria’s history. Through public subscriptions, they raised the money within days, and the paper was back in print.

His feud with Douglas convinced him to get more actively involved, and less than a year later he first put his name forward for public office. Despite the best efforts of Douglas and his cabal to interfere in the democratic process—the sorts of plots that would make even Mike Duffy blush—De Cosmos was elected to the Vancouver Island Legislative Assembly in 1863. He had two main causes: Uniting Vancouver Island with the colony of British Columbia and establishing responsible government.22That is, the duty of the executive to maintain the confidence of the legislature.

That union took place in 1866, and he immediately pushed for its integration into the Dominion of Canada, something he believed would advance said cause of responsible government while also effectively check-mating any expansionist inclinations on the part of the post-Civil-War United States.

People would often find him walking the streets of Victoria in a state of mental distress, alternating between violent rages and crying jags. By 1895 he was declared officially insane, and when he died two years later, his funeral at the Ross Bay Cemetery was a sparsely attended one.

In May of 1868, he founded the Confederation League, an entity Woodcock described as “the first body resembling a political party ever created in British Columbia.” Its aim was, as De Cosmos said at the time, quite simple: to effect Confederation as speedily as possible and secure representative institutions for the colony, and thus get rid of the present one-man government, with its huge staff of overpaid and do-nothing officials. British Columbia officially entered Confederation on July 20, 1871, and De Cosmos was elected later that year as one of six members of parliament to represent the new province.

He continued to sit as a provincial legislator—there were no rules at the time prohibiting dual representation—but Lieutenant Governor Joseph Trutch passed him over to become the province’s first premier in favour of an obscure lawyer named John Foster McCreight. “Though De Cosmos had undoubtedly played a great part in bringing British Columbia into Confederation,” Woodcock wrote, “[Sir John A.] Macdonald was not a man to allow gratitude to interfere with political tactics. He preferred conservative and manageable men when he could get them.” McCreight fit that description perfectly, but after a few months of his incompetent leadership, the province’s reform-minded legislators (led by De Cosmos, of course) moved a vote of no confidence. It passed by one vote. Trutch had no choice but to ask De Cosmos to form a government.

He was an able premier, and pursued a reform-oriented agenda that focused on the development of public institutions along with the completion of the transcontinental railway promised as part of the deal that brought B.C. into Confederation. But he got tripped up in a conflict-of-interest scandal that ultimately forced him to resign as premier on February 9, 1874—the first in a long line of British Columbia premiers to stand down due to ethical breaches.

He remained a federal member of parliament, albeit a mostly undistinguished one. In 1882, he gave a speech articulating an early (and prescient) form of Canadian nationalism. “I see no reason why the people of Canada should not look forward to Canada becoming a sovereign and independent state,” he said. “I was born a British colonist, [and] I do not wish to die without all the rights, privileges and immunities of the citizens of a nation.” It was his final public act. His constituents, the vast majority of whom still treasured their connection to the British crown, disagreed, and they voted him out of office for the last time.

His eccentricities multiplied in his later years. People would often find him walking the streets of Victoria in a state of mental distress, alternating between violent rages and crying jags. By 1895 he was declared officially insane, and when he died two years later, his funeral at the Ross Bay Cemetery was a sparsely attended one. That angered Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken, his contemporary and frequent nemesis, who wrote a letter to the Colonist describing his frustration with the way De Cosmos’s contributions were already being overlooked. “Such a funeral is neither worth living, nor dying for,” he wrote. “Is honour and glory, then, a mere temporary public gaseous emanation, like the will-o’-the-wisp, leaving no trace behind, only beautiful and deluding while it lasts?”

De Cosmos has continued to molder in obscurity. Maybe it’s because of the unlucky combination of his life’s troubled final act, his comparatively minor impact on the national stage, and Canadian history’s natural bias against people who lived their lives on the nation’s periphery. As Woodcock pointed out, De Cosmos didn’t exactly do himself any favours when it came to his contribution to posterity. “He concealed his private life so adeptly that one often wonders whether he had one,” he wrote. “There is no evidence that he kept a private journal; he wrote no memoirs, and no letters in his hand that could be called intimate have surfaced; for all we know he may have written none, though this seems unlikely. By changing his name he removed himself from his past; by covering his tracks he largely removed himself from a future.”

But maybe it’s on us. For all of our cosmopolitan worldliness, Canada is still a place that has long held values like competence and stability aloft over more tawdry ones like ambition. That preference is even inscribed in the British North America Act, where “peace, order and good government” were identified as the new nation’s defining principles; it continues to show up in our choice of political leaders. Pierre Trudeau, Rene Levesque and Danny Williams are the exceptions, not the rule. We like our leaders dull and predictable: witness the success of Stephen Harper, the decade-long snoozeocracy of Dalton McGuinty or that bizarre, inception-like moment in 2003 when everyone actually seemed to believe Paul Martin would make a great prime minister. Given that standard, maybe it isn’t too surprising that historians have chosen to overlook De Cosmos in favour of his less colourful contemporaries.

Whatever the reason for Amor De Cosmos’s lack of notoriety, it’s a condition that needs to be rectified. His life story reads like that of a character pulled straight out of the script of a Deadwood spinoff, equal parts W.B Merrick and Seth Bullock (like Bullock, De Cosmos had a habit of brawling with political opponents when it suited him) with a bit of Al Swearengen mixed in for good measure, if you believe even a fraction of the gold-rush rumours that followed him in his younger years. Where are the schools built in his name? Where’s his Paul Gross-starring CBC miniseries? Manitoba has Louis Riel. Quebec has Samuel De Champlain. Ontario has George Brown. Newfoundland has Joey Smallwood. And British Columbia has Amor De Cosmos. He’s earned his moment.