While I sleep my iPhone works, accumulating email and twining Twitter threads, throbbing with update alerts for apps last updated only the day before. By seven o’clock it’s had enough and hits the marimba wake-up music like a hungry dog with a dish in its mouth: feed me, play with me, be as absurdly productive as I am. Each day begins thusly: what have I missed? Digital commerce measures success in “eyeballs” and mine have been closed for six to eight hours, so I’m behind not only on work but on my daily duty to be advertised at. I’m a bad capitalist: by sleeping I have done nothing to contribute to shareholder value. But the machine will fix it, give me the hypertools to make up for lost time.

Marx had an inkling of this problem: technology, he said, took the means of production away from the worker and rather than lessening his load only increased it. He was talking about things made of pig iron that ran on steam, but the idea applies to that which plugs in and allows us to work ‘round the clock, except for those few hours of Forced Counter-Productivity. Sleep, if you will, is a subversive act. “The huge portion of our lives that we spend asleep, freed from a morass of simulated needs,” writes Jonathan Crary in 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, remains “one of the great human affronts to the voraciousness of contemporary capitalism.” As a bloody call to arms this runs a bit thin, acknowledging as it does that all that’s left is to Occupy Dreamland. They can take away our pensions, but not our God-given right to be unconscious, unconnected, and drooling for at least a few blessed hours.

I don’t pretend to understand Marx, but I think he had more ambitious goals in mind, along the lines of challenging voracious capitalism whilst awake, too. But, as we see with Crary, there’s never been any consensus about what Marx really means, what he was up to: the Maoists had one idea, the Russians another. The Autonomists, Feminist Theorists, Deconstructionists, the Social Democrats, and now the Sleepists all chase circles around a historical figure who means, it turns out, what you want him to mean. Genius or joke? It depends. Sleep on it.

In any case, history has granted Marx the one prize: he remains interesting and timeless, like Mickey Mouse. He’d make a great character in a Doctor Who episode: bring him out of the 19th century and show him post-communist Russia and see what he has to say. In fact this is just what the Spanish writer Juan Goytisolo did with his novel The Marx Family Saga 20 years ago. It’s a strange and complex novel (the author rarely uses capital letters so it reads like a fever dream), deliberately goofball but with a critical heart. Goytisolo asks, who was Marx? There’s only one way to find out: bring him back from the dead and ask him.

So it’s 1993, the Soviet Union is over. Albanian refugees are jumping ship in Italy looking for a new utopia to replace the one they just lost, such as it was. They wave photocopies of American dollar bills, kiss strangers on the beach. They’re up for a little capitalism for a change. All this unfolds on the TV news (the scene is based on a true event), and back in England, watching from their couch in the living room, is Karl Marx and his family and their housekeeper. We don’t know how they got there. They’re just there. He’s the same Karl Marx as the one we know, or think we know: author of The Communist Manifesto, advocate of revolution. He still goes to the British Museum every day to work on his papers, tries to earn enough money writing to feed the wife and daughters. He watches events in Moscow and hears the voices of his critics, saying I told you so. Theory is one thing. Real life is another.

Enter the unnamed author who wants to write the Karl Marx story. His publisher is interested, as long as it’s the real story. “Facts!,” he says. “Facts are what our lady and gentlemen readers are after! put an end to mystifications and oneiric visions which are of no use to the general public and give them Facts! a single Fact is worth more than a thousand poetic digressions and scenes of fantasy!” Easy enough: Marx himself lives in Hampstead. Talk to the man. The trouble is that Marx is evasive, talks in circles. The facts prove elusive: more than 140 years after he wrote theManifesto, the confounded and complex character of the real man remains lost in myth.

What the publisher wants, of course, are the facts, but only if they add up to a tidy, sensible story, to fuel book sales. Meanwhile, everyone the author meets, including a panel of academic “experts” on a TV talk show (where he’s invited to discuss the work-in-progress known as The Marx Family Saga) disagree on the real story of Marx and Marxism: the Feminist Author, the Oxford Professor, and the Spanish Anarchist all see a different man with different (and, generally, wrong) ideas about class struggle and the course of history.

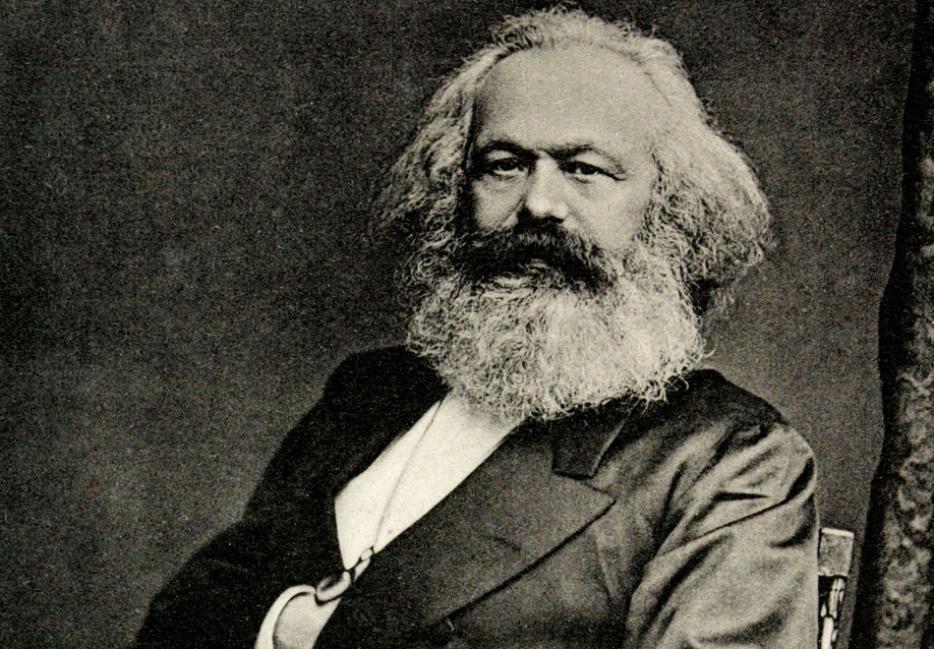

It’s all a madcap exercise in meta-fictional swordplay: the book about the making of the book you’re reading, a satire on the slippery nature of truth. But inside The Marx Family Saga is a serious political novel itching to get out. For Goytisolo, Marx is still very much alive in the present day. He’s reviled and adored; both, in some cases, at the same time. Poorly dressed graduate students stand outside university libraries and hand out pamphlets in his name. Mainstream politicians use the M-word to undermine the policies of other mainstream politicians. The face is an icon: big mess of beard, caterpillar eyebrows, like the opening act at the Winnipeg Folk Festival. In short, Karl Marx is a commodity. The real Karl Marx who wrote in the British Museum, worried about his next paycheque, played with his kids, argued with the wife, died (the Facts!), is irrelevant to the one that’s been bottled and sold as the perfect consumer item: he is what you want him to be, hero of the working class or enemy of progress. Less filling, tastes great. That, for Goytisolo, is the chilling triumph of capitalism.

Marx said that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce. We’re at the farce stage of the program. Now, if there’s any breath left in the revolution, it only exists in your sleep. For now, the marketplace can’t reach you there: your dreams are not sponsored by Land O’Lakes Margarine. Not yet. To be safe however, think about unplugging the WiFi before you go to bed.

The Lost Library: forgotten and overlooked books, films and cultural relics from Tom Jokinen’s overstuffed Ikea bookshelves.