Sarah Meehan Sirk’s debut shorty story collection, The Dead Husband Project (Anchor Canada), is filled with pieces that amble along quietly until the reader realizes they have been thrown into the middle of an unsettling, life altering moment: the wait for a phone call with the results of an HIV test, or the immediate aftermath of the grisly death of a loved one. In the title story, an artist named Maureen is planning an installation around her terminal husband’s dead body, but is forced to change her plans when his health takes a turn for the better. In “Ozk,” a genius mathematician’s life’s work serves as a point of isolation for her introverted daughter.

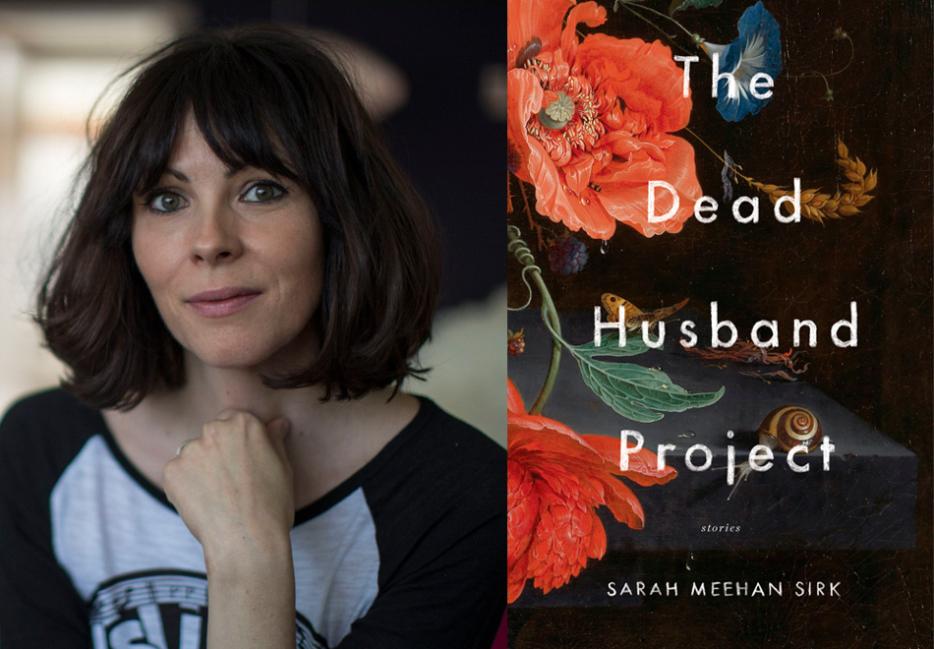

Sirk has worked as a radio producer and broadcaster for the CBC, and hosted the series Stripped, a show that explores the body inside and out. Though she’s had fiction published in Joyland, Taddle Creek, and PRISM international, she is still adjusting to her identity as an author, and mentions to me after our interview how weird it is to be on the receiving end of so many questions. Yet when asked about her stories, Sirk jumps to life with detailed answers, eager to bring me into the winding worlds of her characters.

Anna Fitzpatrick: You've produced at the CBC, and you covered sports and crime earlier in your career, and now you have this book of short stories coming out. How did you get started writing fiction?

Sarah Meehan Sirk: I guess it was always in the background. In my early twenties, probably in university, there was a significant pull in the fiction direction. I just was kind of tinkering around. I started taking some of those continuing ed courses at Ryerson, wanted to do the Humber school, was thinking of doing the MFA but didn't have the money, but I was writing. I was starting to play around, and had writing groups, and was doing that on the side.

What did you major in?

Math and philosophy.

You got some math in the book. I mean, you got a lotta philosophy but you got some math too.

It's funny you say philosophy, because I've had a hard time to—wait, are we interviewing now?

Yes, the recorder's on. This is my fancy interview voice.

It's been a bit difficult trying to synthesize the stories, to talk about them. I wrote them over seven or eight years, and I certainly didn't have the intention of linking them when I was writing them. But that being said, I was thinking about stories and writers that have influenced me. I mean, I was shocked into a new level of awareness or something when I read the Wall by Jean Paul Sartre. When I was in philosophy, and when we got into the existential branch of thinking, that felt like, "Ok, here we go. These guys are speaking my language." Only in the last few days, honestly, when I've looked back at what I've written in these stories, I feel like almost all the characters are in these clear moments of crisis that are very human but also, they're disconnected. They're adrift. In some cases sort of obviously searching how to reconnect, but in other cases they're just longing for that reconnection. And in that moment of crisis, they seem to be confronting some very real, difficult questions about themselves and about loneliness, and I think that they're sometimes very awkward and difficult places to be, but I think that some of the most beautiful and real stuff comes out of that. I didn't mean to do that. That wasn't ever, "I'm going to do something existential," but I'm now seeing some of that influence in the stories.

Well that answers all my questions. Good talk.

Oh no!

No, I'm kidding. You've got a lot of wham moments in the book, where characters get in car accidents, or make these amazing mathematical discoveries, but all the stories are very tight in a way, very internal.

Well, I hope so. I was working full time. Many of the stories were written before I had a child, but some of them were written while I was pregnant, or after I had a child. My relationship to time changed once I had kids.

How old is your oldest one?

He just turned four. I think, in writing short stories… I never thought about writing anything else, to be honest with you. It wasn't like, practice to become a novelist. I felt like I could do the most in that form, with the time that I had. With short stories, to paraphrase something George Saunders said after writing a novel, you don't have as many balls in the air. You can kind of do more with the balls that you have.

You can just narrow in and focus and not have to worry about where those characters are going to be in 200 pages.

Yeah, and how they connect to something in 200 pages.

You said you weren't looking to synthesize your stories, but did you notice any other links when you were deciding what to include in this collection?

What I decided to include was, full disclosure, the best stories that I had. I was pregnant with my second child, and had this manuscript essentially done. I was ready—well, I was fearing going back full time without sending out this manuscript. Without knowing if there was going to be any interest in my writing, because I didn't know what I would be able to do, and I had two small children and a demanding full time job with respect to writing. It really was the best that I had. But to go back to whether there's a theme, looking back now I can see there's a yearning that's in each of the stories, and most often it's a yearning for a connection.

You wrote some of these before you were even pregnant with your first child. Being a mother is such a thematic recurrence. In the very first story, the title story, you have Maureen who is an artist, and you start with her as a newlywed and jump ahead twenty years, and she's a mother. She's at a talk, hearing a young successful artist, Claudette, speak. Someone in the audience asks her for advice, and Claudette answers, "Let other people have kids." It's considered this feminist statement, like, "Oh, it's ok to put your career first!" And then Maureen's baby starts crying at that moment. What do you make of that?

I'm so glad you touched on that, because that means so much to me, that moment. That's a piece of advice I'd read. I think my son was just born, or I was pregnant. Either way it was a kick to the gut, right? It's not like I hadn't heard that kind of thing before, but it was...when I read it, it was at the end of a list of advice to writers. The number one thing was, let other people have children. And I couldn't let that be true.

There was that debate a number of years ago, Zadie Smith had gotten involved, when somebody had surmised that the ideal number of children to have if you're going to be a writer as a woman is one. And everyone said “That's absurd! You can't look at things that way.”

However, I understand where that advice comes from. It is very difficult to write and probably do a lot of things, but I find it difficult to write and be a mother because in some ways, there is that pull in a different direction. The amount of time you have to do your work significantly changes. There are other things on your mind. Your perspective on the world changes. For me, that also opened a whole other understanding of things. Not only did it make me feel like, as one of the writers had said in that debate, you realize it's not about you. But there's a new connection that you have to other people who are parents, to an understanding of looking at the world in a completely different, wonderful way, like a child does. Personally, it made me do this. It pushed me forward, harder. I didn't say, "Ok, well maybe my writing's going to take a back seat." Absolutely not. I said, "I want my children to see that just because you become a parent, it doesn't mean the things that mean the most to you have to go away. I will prove to you that I can make this come true. I can prove to you that the very pinpoint goal that I have is going to happen." That's been my relationship to motherhood and writing, but I also wanted to take some control of that idea, and put that in a story somewhere because it affected me so much.

It's odd to think that there's an ideal number of children to have if you're a writer, because it turns it into this equation. It's like those debates about whether you should get an MFA or go straight to writing. There shouldn't be a formula for being a writer, because you don't want every book to be written by someone with the exact same experiences.

Well, that's what I think, too. Wouldn't it be a terrible thing if every book that's written is by someone that doesn't have children? What are we missing in that perspective? I feel very blessed and I'm very glad to have that as part of my arsenal when I approach my work.

I read your book while I was visiting my family the other week. I just turned twenty-seven, so I'm at the age now when people are asking me, "When are you going to have kids?"—

Ten years!

I sympathize with Claudette when she was like, "Well, fuck you, I'm not gonna have kids, I'm going to focus on my art." It's such an either/or situation.

It's not up to anyone else! And if you want to, you do. That's part of the wonderful thing. It's up to you. If that's what you want to do, great. And if you want to go the other direction, great. And you'll make it work. You'll figure it out, right? Most of the time.

So you wrote that before you were a mother?

That story started as a novel. As an attempt at a novel. I was pregnant with my son, my first born. I had originally started writing it from the daughter's perspective. They had moved out to the country, the father was convalescing after being cured of what had been, they thought, a terminal illness. She was watching her parents deal with this strange new relationship they'd had where her mother had been coming to life as her career was coming back to life, in direct relationship to the daughter's father dying. My agent was the one who said, I love this concept but I want to be with the wife. I want to be in her head. I found that—I was scared a little bit. I didn't want it to be cartoonish, and I didn't want her to be evil. I wanted her to be ambivalent and conflicted and not fully aware, I don't think, of what she was, of what the full implications of what she was doing were until they realized he wasn't going to die. Then she's forced into this moment of "Wait a second, I kind of think I wanted him dead. Why?"

You see that he's this more prolific artist. He certainly has more confidence in his work than she did. He boldly pursued his work, his art, throughout their whole life together, and she was picking up sort of the details of life. Had a bit of a flailing attempt a few years after her daughter was born that didn't work out so well, and essentially just completely swept it under the rug until there was an opportunity. I think they were roles that they just fell into, but I think it, you know, as I said, I didn't want to—it felt like dangerous terrain to even start considering....

That mindset?

That mindset! Yeah.

I just read Elizabeth Hardwick's essay collection Seduction and Betrayal because another person I interviewed for Hazlitt a couple of months ago told me to read it. They're essays about women and literature, but she writes about women adjacent to famous authors, like Zelda Fitzgerald and Dorothy Wordsworth, and a lot of it grapples with the idea of this second genius in the family that didn't get the same advantages. An interesting thing you dealt with in your book is that the reader doesn't know if Maureen is actually more talented than her husband. It's not a matter of like, "Oh, she's the real genius." He could very well be a better artist. It's about how she just never went for it. You don't even know what the levels are, because it's not about that. It's not about who's more talented or who deserves it more, it's who has the permission to even pursue it.

I think that's a really good way of putting it. I don't know how conscious I was of who was better, because as you said I don't think it was about that. I think we, naturally, in coupledom, can fall into roles. Sometimes one person's pursuits can take up so much space in a relationship that it just doesn't feel like there's space for the other person. And maybe they're not conscious of that. It's just sort of you, it's a rhythm that you can fall into. With Joe dying, and it was his idea in the first place too, to use the body of the other in a work of art when one of them dies, she starts to feel that she can breathe. She starts to feel like, "I've got these ideas! Things are making sense! I start to feel like myself! I'm reconnecting with the person I was a number of years ago." There's a scene that jumped out at me when I reread it, that wasn't intentional. I don't know if I'm supposed to admit that. Near the end of the first scene, he essentially smothers her, and blocks her view of the thing that's inspiring her. Which he doesn't know about, it's in her mind. But that is essentially a metaphor for the rest of their relationship.

You follow up "The Dead Husband Project" which "Ozk," which is about a daughter dealing with a mother who's the opposite of Maureen. She just goes full into her passion.

I think it was always fascinating to me. Because I was conflicted too. The more writing I was doing, the clearer it became to me that it was really what I needed to do, as I was going through my twenties and into my thirties. At the same time, as you said, you hit a certain point where everyone starts looking at you a different way, and thinking "When are you going to start having kids?" I think that must have always just been in the back of my mind while I'm writing, and I think that's an incredibly significant relationship to say the least, and so much can be mined in the difficulties of that relationship, when you have two very particular characters. I don't think the mother in Ozk is an awful person. She's more of a savant who had a different ability to be connected that her daughter, who wasn't a savant, didn't fully understand.

In the first story, you have this third person narration, where you're in the mother's head a lot but you flirt with other points of view a little, the second story is strictly the daughter's point of view, and then the third story, you've got the mother's perspective, but she's talking to the husband. It felt like you were looking at this concept from all angles.

I guess I was. I should sell it like that! I meant to do that.

Then in the fourth story it's something totally different, so there goes my theory.

"Motherhood in crisis" should be the subtitle.

Well, when I was writing my questions for this interview, they were all about motherhood. And I thought, "It's reductive that I'm going to go talk to a woman author and then focus on her being a mother." But then it's reductive that I think it's going to be reductive. That overthinking it.

Of course.

You don't want to talk to an author and be like, "So, you're a mom, what's the deal with that?" But I don't want to dismiss it.

I want to talk about it. I feel like, I've done a lot of things. I've had a good career in broadcasting, I did some interesting things in university, I waitressed for a long time in between and was figuring stuff out. I don't just define myself as a mother who's a writer, but my children are not in school yet. I have one who's in diapers. As any mother will know, as any parent will know, that occupies a tremendous amount of your mental and emotional space, if not, like, 95% of it. So to be doing this kind of work, which is mining your deepest feelings and truths and things like that, I think it'd be disingenuous for me, in my experience. At the same time, I feel like there's a lot of things that I had been drawn to in relationships, in motherhood, in parenthood in general, because there are a couple of stories that are from the male perspective, where there are these disappointments and regrets and uncertainties and the loneliness that you're not really supposed to talk about, still. There's some stuff that's out there, but it's not something that you get into with someone until maybe you've been talking to them for a long time, and then you start bringing this stuff up. And there could be a lot of apologies around it or guilt, and "I know I shouldn't really be saying this, but..." That's the kind of stuff I like to write about. I think there's a lot of that stuff in these stories, those very real, hard to deal with feelings that are part of that stage in life.

The question of, do you want to be an artist or a mother, it's like, "Well, don't mothers have a lot to say?" It's something that so many people experience, but can still be unique to each person. Motherhood represents this huge swath of humanity that's been largely brushed aside in art.

Like, it's just going to be too much of an interruption, is how I felt it can be defined. And like, Zadie Smith has two children, and thinks it's absolutely absurd that you can put any limit on the number you can have. And she said, "Was it a problem for Dickens to have ten?" Of course, it was a different time. And Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon, they have four children. Is it just a problem for her and not for him? But I don't overthink that as much as I might sound like I do.

It's ‘cause I'm asking you all these questions.

But I related to Claudette. Believe me, when I was 27? I didn't start having kids until I was in my mid-thirties. I would have been Claudette for sure, for a very long time, that's exactly how I felt. I wasn't sure. And the other thing, the writing, was more important at that time. Or getting to a place where I felt strong enough with it. So you can be both!

Whenever someone says, "You're going to want to have a kid someday, you'll change your mind," the instinct is to push back. And I don't know if I do or don't want to have a kid, but then you're forced to adopting this stance, "Well now I'm never going to."

Exactly! And there becomes some animosity and weirdness around the whole idea of it. Now I have to navigate it under your watch. It can become so complicated. But it made me write. It made me write, honestly, in so many more ways. I had to become better with my time. My son didn't sleep at first. I originally thought I was going to write a novel on my first maternity leave, and you can laugh, and you don't even know how insane that is to think about. Unless you have a good sleeper. But I didn't. And when he started napping after eight or nine months, I had an hour in the morning. I had never done more with an hour than I did with the rest of my maternity leave in that one slot of day. It was like somebody handed me a pot of gold every single day. It was my most amazing time. I got so much done. Moreso than I probably had in years before. I knew what I wanted. And kids can help you focus in kind of a weird way, in your bigger trajectory. It's a profound life change in a lot of ways, and it doesn't have to take away from your art.

What area of math did you study?

There wasn't a particular area. It was an undergrad program. I started in a couple of other things. I was in this program called Cognitive Science and Artificial Intelligence at the University of Toronto for a brief time.

That sounds fancy.

It was brand new and it was fun to say. I loved it. I loved the people that I met. It was like the island of misfit toys, but the smartest and most interesting people that were into art and science and all kinds of stuff. But the computer science side and I were not friends. That was not going to work. But I loved the math and I loved the philosophy, and that's how I ended up double majoring in both. I have regretted for a long time, as my writing became more and more of a serious pursuit, that I hadn't done in undergrad in English lit.

I was an English major and I always wish I did math.

Really?

I love number theory. I mean, I read the pop science books about it now, that explain it in simple ways for people who didn't study math. But I loved math in high school. I felt like being an English major was a really easy thing to fake.

I don't know why I didn't. I can't remember. When you're eighteen, nineteen, you just kind of go with whatever feels good.

I had these romantic aspirations of, "I'm gonna read literatuuure" and now I'm like, I can read books on my own, I can't teach myself the more complicated math.

Yeah. In the higher levels, you're doing a lot of proofs. They could take a long time. I certainly wasn't a savant. It took me a little while to get the concepts, but once I did, once you get locked into a proof, it's meditative. It's amazing. I loved it so much. I could sit on the fourth floor of the library by myself for hours. Hours would go by, and it was just this beautiful flow from one line to the next to the next until it's natural conclusion. The only experience that is like writing to me is that. I don't mean anything I've done journalistically is like that. What I think a big part of the pull was, and it was not something I ever had words for at the beginning but there was a pull, once writing was going well, and it certainly doesn't happen all the time, but when you're locked into it there's a natural flow from line to line to line to this logical conclusion. You do feel like you're elsewhere. When it's going well. I should emphasize. When it's going well. I don't want to be overly precious about it because it's not like it's like magic, but it feels like it's about the proximity to truth.