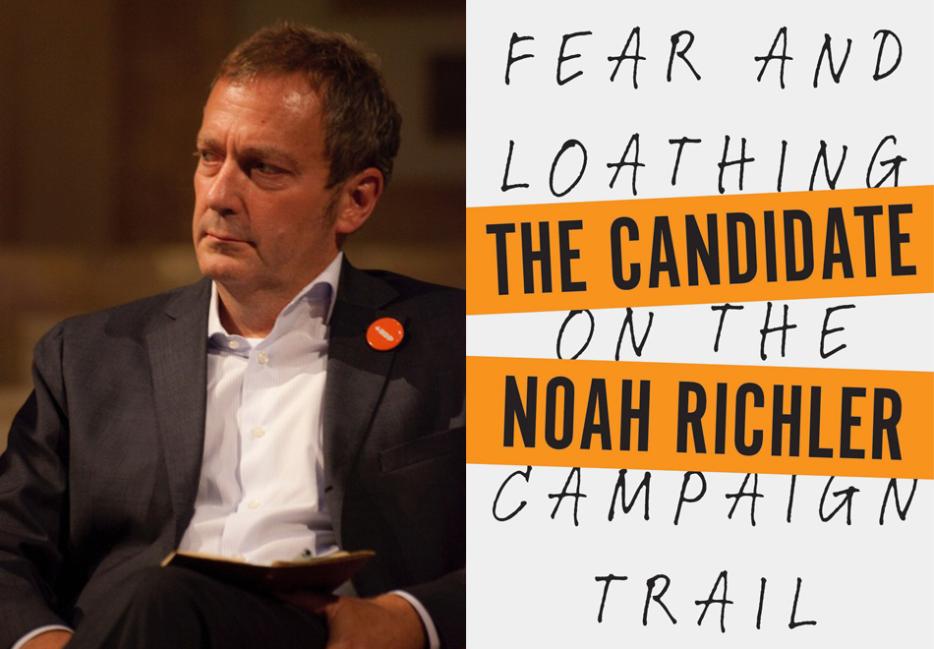

Politics is a lot like writing—or so according to Noah Richler. The longtime journalist and author of This Is My Country, What's Yours? and What We Talk About When We Talk About War says it’s all about tossing ideas out into the pond of communal consciousness, letting them ripple outwards and have a life of their own. And now, the one-time NDP candidate is sharing his thoughts on his failed political experience in his latest book The Candidate: Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail. (Full disclosure: the book was edited by Hazlitt EIC Jordan Ginsberg.)

The book, which coincides with the one-year anniversary of the 2015 federal election, brings readers into the mind of the candidate fighting an uphill battle in the riding of Toronto—St. Paul's. Richler’s personal account shines light on the behind-the-scenes political operatives, the challenges of campaigning in the era of social media and includes humorous glimpses of what could have been his reality had he won his seat.

While Richler was just one out of 338 candidates running for election within his party, his ambitions pushed him to run a different kind of campaign—or at least try to. As a political neophyte, he succeeded in gaining national attention, and upsetting his opponents, with a series of online video spoofs, including one in which Richler inserted himself into a previously aired Harper interview with Mansbridge—only in this one, he removed Harper’s Canada pin from his lapel and gave him the boot. The video had to be taken down. Richler’s days of political campaigning may be a thing of the past, but he still won’t give up a good opportunity to release another humorous video poking fun at those on the inside.

Don’t be fooled by the orange band on the cover, the author says he hopes his book goes beyond party lines and serves anyone and everyone who wants to learn about politics in Canada.

I sat down with Noah Richler before the federal election’s one-year mark to talk about his book and lessons from the campaign trail.

Arielle Piat-Sauvé: Why did you decide to write the book after the campaign?

Noah Richler: I didn’t enter the campaign to write about it and that's important to me because I didn't want anyone to feel like they were being manipulated or used. There were a couple of moments during—one that I remember in particular—where I thought it would be funny to write about this. I was at a meet-and-greet in a wealthy part of the riding, there was a TIFF party going on and the owner of the house had a big sign on his lawn. The owner said he wanted to look at his sign and so we stepped out. There were valets moving the cars of big players and stars arriving, and he looks at the big orange NDP sign and said: "Does it come in any other colours?" He wasn't joking. At that point I thought there probably is material but I still hadn't meant to write about it. Then Scott [Sellers] of Penguin Random House and I had a chat, and thought it would be fun to have something come out on the first anniversary of the election.

The book starts off with you imagining what it would have been like to win the election and there are a couple of other passages in which you write about things that didn't actually happen. Why was it important for you to include those fictional elements to the book?

First of all, if it works it will be read across party grounds. I certainly didn't intend it as an NDP platform or policy book of any kind. I wanted it to be enjoyed by people who never thought of running, by people who support their parties, by the politically interested. But as a writer, it's my job to entertain. I love structure and I love form. So I thought there couldn’t possibly be a candidate who hasn't thought about what it's like to be in power—that’s what drives you a lot.

You write that you had thought about running in the past. Why did you decide this was the right moment for you?

Principally because I was completely fed up with Harper and I found his speech after the Charlie Hebdo attack just beyond the pale in terms of trying to spook the Canadian public. I've always thought of my writing as fairly political anyway and so I thought, it's important to put your foot in the ring. It's not so much in the Canadian tradition for writers to put themselves forward that way, but it's more common in other countries—and I just thought, now is the time. And though I think I'm done, I completely applaud the NDP for what it's contributed over time and insist on the necessity of a third party. After the NDP lost, there was a tsunami of columns saying, what's the point of the NDP, what's the point of a third party? I do think they are the only guys standing up for those who need representation the most, and I'm glad to have done that. I feel like I chose the right bunch.

What did you feel like your chances of winning were?

Initially I ran to get ideas across—that was already naïve. The notion that the NDP had recruited me for my intelligent positions on something or other, as they did [Linda] McQuaig, never happened and that was never going to happen. An election is all about human resources. I was happy to run wherever and the idea of winning didn't matter to me. I was there to make a point about a refurbished party. That said, as soon as you start running, you have to believe that you can win because if you don't you are asking all sorts of people to give their time, money and resources to you in bad faith. So you operate thinking that the winds of favour might blow your way.

You wanted to use social media and make all these videos, and you were able to do a lot of that. But looking back after writing this book, did you achieve that new kind of campaign you set out to do?

I think we did very well within our means. We made two videos that indisputably went viral and one that really irritated the Liberals and the CBC, and the NDP was too cowed at the time to do anything about it. That was fun and if I were to do it again I'd do that as well. That said, even with the extraordinary unprecedented success of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on social media, I think it's still an open question whether this makes much of a difference. One of the fascinating conjunctions of politics and social media is that I don't know if these things actually change people’s minds. So my first video was seen within a day and half by 150,000 or 175,000 people, which was staggering for us. It did a lot of good things for us and it got me name recognition in the city, put me on the map with the party and put me on the map for the Liberals. But I don't know if it actually won me votes.

Early on you talk a lot about the candidate vetting and how you were open with the party about your past. But, as we know, some Facebook posts did slip through. There was your criticism of actress Jennifer Lawrence, your comments about racism in Quebec and one post in which you referred to Harper as a pathological psychopath. Given all this, how do you feel about the whole vetting process?

I was trying to play ball. They did vet and I probably had too much confidence in the job that they were doing. My wife Sarah, and even a couple of people from the campaign team, came up with these posts I had written. To my mind I had taken them down because they were only viewable to friends on Facebook. But of course why did I assume a Facebook friend is my friend? My pages were obviously scoured. La Presse, The Ottawa Citizen and the Star all had different posts that were clearly to my mind handed to them. It's not a surprise; it's what campaigns do all the time. What I regret is that the NDP didn't let me do what I wanted which was to publish a piece in the paper saying sorry, I’m not apologizing. If we are going to have politics, we are going to have good decent people—and I think I am—then we have to stop this.

On September 25, 2015, you launched that first video. How did you feel when that first came out and the response you got?

That was great fun and felt really good. I know as someone who had worked in production for a long time just how extraordinary it was that we were able to stitch those together in the time that we did. One of the surprises of the campaign for me was just how blinkered you are and how little action in concert there was. I'm not intending to run for leader but I know if were I to be in that position, I would have done whatever I could do make virtues of the 338 people running across the country.

Your second video with Stephen Harper and Peter Mansbridge led to CBC threatening to sue. You write that you were surprised the complaint came from CBC and not the CPC. How did you feel when this all unfolded?

This was a symptom of just how on edge the NDP was that they caved. In any other large organization I've worked for, if you make your case for something and you check that it’s legally sound, and if your bosses say yes, we are going to do it, then they go with you to the wall. I had had the Harper video sanctioned by the NDP and then they caved. That being said, my campaign was one out of 338 and I am enormously sympathetic to their job of having to manage the human resources of a campaign.

As for the CBC, I basically think that the CBC is so injured after so many years that it is constantly in survival mode and that it is prone to acting childishly. There was no way this was demeaning the reputation of their news operations or Peter Mansbridge as anchor. I mean, you have to be out of your mind to imagine that this was a genuine broadcast. I think a less defensive organization would have just let it go and enjoyed it and furthermore would have covered it. I can say this as a guy who has worked for news organizations on and off for 25 years: a nobody on the campaign who makes a video that goes viral that really upsets the Liberals and that leads to a storm, that's a story. So they were both condemning it and not addressing the news, and I think that's a problem at an organization that is in survival mode—its editorial decisions are compromised by its instincts of survival.

You seem to have become a natural campaigner. You say you enjoyed the canvassing element a lot. Was that a surprise to you?

I think it surprised people around me and some who knew me very well like my wife, Sarah, more than it did me because I worked in radio for 15 years in Britain and then here, and radio, as you know, depends on talking to people and forming relationships with all sorts of different types and I used to love that. That is in a sense what we were doing at the door. It was more fun when we thought we could win.

You took this election personally, so how did you feel when you lost?

A terrible bruised ego, I mean it was ridiculous. I really felt like the whole of Canada had rejected me and that's because you get so emotionally invested in the thing. People told me it would take time to recover and it did. Actually the book was one of things that helped me.

One year later, what do you think of the future of the NDP?

People picked on Mulcair for being quite quiet this summer but what else was there for him to do? Right now we are looking at a strange period where it sort of feels like we are living in a cult more than a country where nothing matters and nothing sticks—and that is mostly Harper’s fault to my mind. Now the Liberals moved into Ottawa like it was going to be theirs for 12 years—not even eight. Just owning the town. And part of owning the town is claiming $100,000 or more to move and taking $50,000 in cash. That may seem like nothing at all and it is nothing right now to the Canadian public but that’s because at the moment we are just exhausted and relieved that it’s not four more years of Harper and the Kellie Leitch gang. That will pass.

So do you think you'll run again?

I don't think so, no. The only way I could, would be without the innocence I had going into this particular campaign. I'm happy where I am and I'm by and large happy with where Canada is.

Have you had any more dreams about Justin Trudeau?

No, I've stopped the day dreaming for the moment. Probably back to being an athlete—just kidding. But those dreams were funny during the campaign.