“Breathe deeply.”

I'm wearing a hospital gown in a dingy basement that smells like Salisbury steak. And, as it happens, I'm breathing.

Thirty seconds later I'm back in the sweater I'd left crumpled on the linoleum floor. It smells, too.

I'd waited a week, plus two hours in the lobby, to land an appointment at this cash-only clinic in Toronto’s Little Italy neighbourhood, where the doctor’s 50-year-old medical school credentials hang askew on discoloured drywall. I’m here to receive a physical, x-rays, blood work, and urinalysis. Another projected six to eighteen months of waiting, and I'll be awarded the prize of Canadian Permanent Residency—following eight years of impermanent residency with the occasional hiccups characteristic of prolonged transience.

But for now, a chest x-ray taken quicker than an Instagram.

The word “immigrant,” implies outsider-ness. And the images it often conjures here in Canada don’t apply to me, a speaker of fluent Upper Canadian born and bred within the same Great Lakes region as my adopted Toronto home. But like everyone else looking to make a forever home in Canada, I too have put in my time at the smelly Citizenship and Immigration Canada-approved hubs that exist primarily to determine the physical eligibility of Canadian hopefuls. In my vintage eyeglasses and battered Mountain Equipment Co-op backpack, I am acutely aware of how different I appear from the neatly-attired families who chat amongst themselves in languages I can't understand. But I, too, could be turned away on the basis of my physical examinations.

As for the diseases or conditions that can deem a prospective immigrant medically inadmissible: “There are a lot of them, too many to mention,” says Paul VanderVennen, the downtown Toronto-based immigration lawyer I sought for guidance. “Virtually any disease or condition has the potential, if it requires ongoing medication, treatment or monitoring.”

CIC doesn't screen for drugs; just in case, I haven’t touched a poppy seed for two months.

*

In 2004, I made the move from one Great Lakes city (Milwaukee) to another in pursuit of a Bachelor of Arts (it was cheaper than out-of-state tuition within the U.S., and just far enough to ensure no surprise drop-ins from my parents). What was meant to be a four-year hiatus from my Midwestern reality became eight-year resettlement through a series of happy accidents: a relationship, a social circle, and a career. I came to see myself as a Torontonian, to appreciate the relative safety and big-city-offerings of my adopted hometown. I indulged in daydreams involving Dufferin Grove park outings with future offspring. I grew attached to the crazy notion of basic healthcare for all, and the idea of living among others that shared it.

To leave Toronto would be to start at zero.

For real immigrants—the ones who aren't American brats with luck on their side—the process of transitioning from guest to legal permanent resident is a chore of empowerment. We've sat in the same waiting rooms, me diddling away on my iPhone while they read from coursebooks offering keys to New Canadian success, faces awash in serene proactivity. I've seen entire flocks of children sit patiently and well-behaved as I huffed and foot-tapped indignantly. And then I've caught myself, and felt ashamed. When international relocation isn't a matter of life or death, you exist among the refugees and the better-life pragmatists in a state of legal precariousness, but your Back Home is just an hourlong flight away—in a place where people look the same, sound the same, and also wear sweatpants in public. You become, in your own mind, an immigrant with an asterisk.

Being an immigrant with an asterisk is kind of like having a life-threatening allergy to a food you can't normally afford—you can usually avoid it just fine, but you know that one day someone will slip some truffle oil into your salad. My first student visa was issued with a typo that switched the last two digits of my birth year, making me 36 instead of 18—great for waltzing into bars underage (“I know, I know, I look like I'm 12!”) but a near deal-breaker for my re-entry into Canada following that first Christmas break. Third year of university, I lost a market research job thanks to HR confusion over my off-campus work permit. These logistical hiccups were rare, but when they happened, they hit like hard taunts. “You are a guest here,” they seemed to say in a bitchy, bullying lilt, “and your time here is borrowed.” I had wrongly believed that my Toronto life was fully mine.

My post-graduate work permit expires at the end of September, and I will likely have to apply for a temporary extension before my status is granted. Chances are I’ll avoid leaving the country for a few months in between, so no surly border guards can bar my re-entry. I can’t risk being sent back to Milwaukee, to my high school bedroom and a life I no longer own.

*

There's a phenomenon that happens when a person has to pee but, for whatever reason, can't: a prolonged unpleasantness that becomes an unbearable urge once the toilet (or alleyway) comes into view. My path to immigration follows more or less the same trajectory; I didn't realize how badly I needed to start applying until it was almost too late. It wasn't that I particularly enjoyed living on a temporary work permit without healthcare. My day-to-day existence was just too busy with activities more pressing than obtaining legal security, like updating my Facebook and drinking beer with friends—it's easy to let life distract you from life. The proverbial piss receptacle, in my case, was the expiry date of my three-year work permit, which, once in sight, triggered appropriate desperation.

Between 2006 and 2011, immigration outstripped new births in Canada by over 65 per cent. Still, most of the Canadians I know have no clue about what their journeys entailed, so for those spared the indignity of Canada's immigration song-and-dance, a short primer. Immigrants to Canada come in through one of three streams: humanitarian, family reunification, or economic. The current government vastly favours the last category, operating on a now infamous points system that, since its 1967 establishment, has been considered an international role model for other low-birthrate countries looking to boost their GDP. Foreign students educated through the country's post-secondary system are allowed three-year post-graduate work permits—the reason I'm still here. After that, you’re on your own.

Thankfully, I have a sponsor.

“It's time to start applying for residency,” my boyfriend-cum-common law spouse, a sensible man, informed me about eight months before I finally obliged. (He's an American too, but one with permanent residency and the ability to legally vouch for little old me.) We met in an activist group the week after I moved to Toronto, which I'd joined to make friends and he'd joined to save the world. A year later I moved into his co-op house under the premise of friendship. We were a couple within weeks.

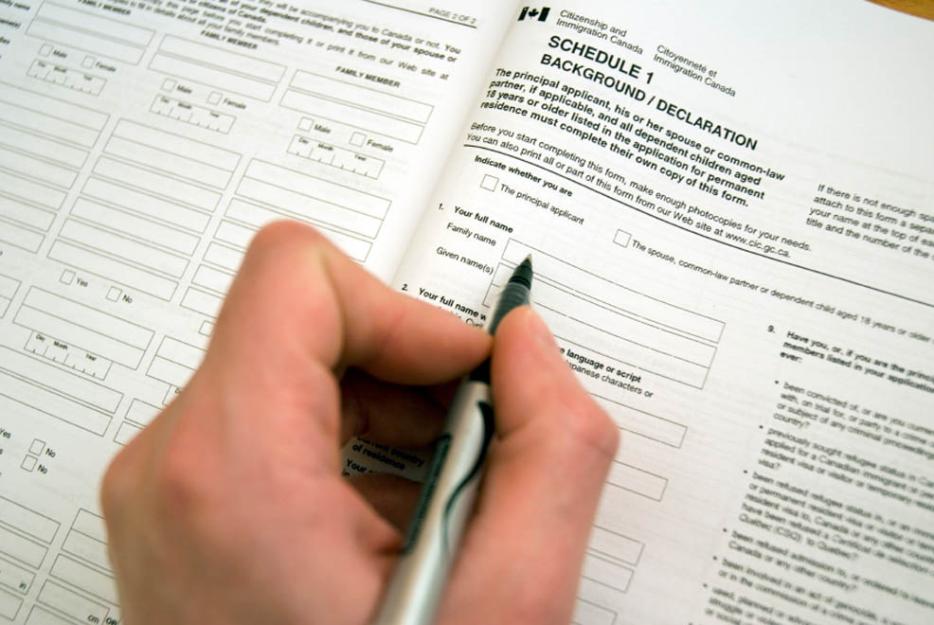

We co-signed our first apartment lease after nearly five years of dating because that's what people do after nearly five years of dating, but also because a year of cohabitation would grant us the legal status necessary for sponsorship and we were racing the clock. But once that first year wrapped up, it wasn't hard to put off application writing and appointment setting even further—self-sabotaging arrogance is, after all, a cornerstone of youth. Once we got around to the last-minute evenings of application kit assembly, my procrastination had made an already unpleasant undertaking almost unbearable. At one point I exploded at him for turning off the special immigration paperwork music playlist I'd compiled, hurling a pen with great force against the wall.

But parts of it were fun, like dredging up six years' worth of ridiculous old photos to prove our love was legit (“They'll totally get how no one else would have dated us!”) and agreeing on the best Coles Notes version of our story to present to the feds.

“Do we tell them we first hooked up on Halloween?”

“Maybe we just them we were housemates who eventually started dating.”

“But university students don't date.”

“They'll get the idea.”

Not the kind of exchange one associates with a night of government paperwork, but Citizenship and Immigration Canada demands much from its spousal sponsors; the application form’s request for lurid details that “prove your relationship is genuine and continuing” just begs for confessionals. One imagines a backroom somewhere in the bowels of the CIC Case Processing Centre where prospective immigrant bodice rippers get read aloud over stale coffee and Peak Freans.

The sponsorship application is the least of my problems, though—a mere drop in CIC's paperwork-induced humiliation bucket. Far worse is the application “kit” all prospective immigrants are required to submit, whether sponsored or not. The barrage of government questioning known as the “Generic Application Form for Canada” necessitates a closer reading than perhaps every literary theory assignment I received during my university career.

“How the hell do non-native speakers complete this thing?” I asked my boyfriend late one night, dumbfounded over a laptop screen at the multiple pages of interrogation. He looked at me and shrugged.

“Lawyers.”

*

“There are many people who are waiting more than five years for a skilled worker visa,” says Lawyer Paul. Spousal sponsorships, like mine, can be processed in as little as four months if there is no interview, but can take as long as two years in some visa offices if an interview is required. And that's if they get processed at all.

A few weeks ago, my boyfriend received a letter from the CIC's Mississauga case processing centre stating that his application to sponsor me had been approved. The package we'd put together of photos, emails, insurance documents, and a co-signed lease was deemed legitimate. His Real Job-fitness to pick up my potential slack was given the rubber stamp.

I imagine my own piece of CIC mail is on its way, too, the one that gives me a SIN number and permission to stay. My lawyer seems confident that it'll go through, and he's seen lots of tough cases so I'm sure he's right. At least that's what I tell myself, because the alternative—a loss of my life as it exists—is a weight too heavy to carry day in and out, asterisk or not.