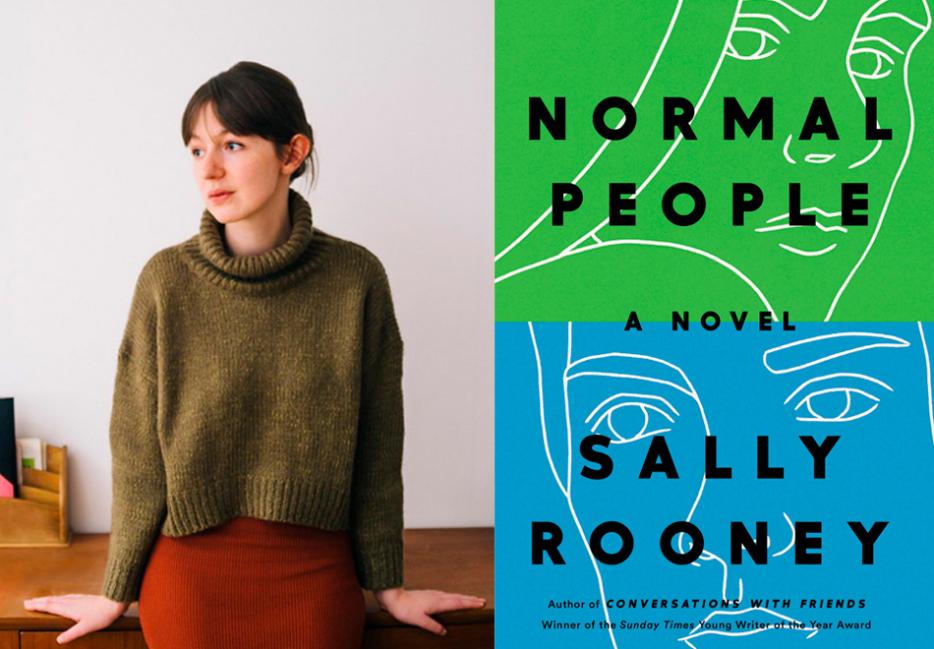

Sally Rooney's second novel, Normal People, is already one of the most talked-about of the year. The book centres on the relationship between Connell and Marianne. Two young people from separate social spheres, they start spending time together because Connell's mum cleans Marianne's family's house. Despite their differences—Connell is popular, athletic, working class; Marianne is ostracized, isolated, and from a wealthy family—they develop a secret relationship rooted in shared intellect and a staggering physical connection. As we follow them to university, the change of environment alters them both, but their connection remains, unconventional and constant.

Many adjectives have been draped on Rooney’s shoulders since she has become a phenomenally successful young novelist, so instead of adding to the list, I will say that the experience of sitting across from Rooney and talking about politics, literature, and music instills the same blend of familiarity and insight that I get from reading her books. There's a warmth to her and a sense that she is someone who is uniquely positioned to capture and reflect on the world she’s living in.

Haley Cullingham: I wanted to start by talking about intimacy, because the way that you write about it is one of the things that I’ve most taken away from your work. Do you have some literary touchstones that have shaped the way you think about intimacy?

Sally Rooney: Whenever people ask me about this, it’s the one question I’m terrible at answering on my feet. I feel like I really should carry around a little list of books, because I always regret when I walk away from the interview, "Oh, I didn’t say this one book that was really seminal for me." But the one that springs to mind I must say is James Salter’s novel A Sport and a Pastime. Do you know that book? It’s a really, really interesting book. And I’m not actually familiar with the rest of Salter’s work, I’ve read some of his short stories, and I’ve read this one book, and I’m sort of working my way through the rest of his work and his novels and stories, but A Sport and a Pastime is, I guess it’s an erotic novel. It’s set in France, it was published in the late 1960s, ’67 or ’68, and it’s a really, really intense exploration of intimacy between these two characters. Nothing really happens in the book other than the development of this really intense sexual relationship. And that book blew me away when I read it. And I think a couple of critics have spotted [it], purely because of the depth of the influence that book had on me I’m sure. But that book was something that made me feel like, "Oh, it’s possible to construct an entire novel about and propelled by sexual desire." Like to have that be the kind of momentum of the narrative. And there have definitely been other contemporary books as well.

Intimacy is the one I keep returning to, and desire and intimacy. I think it fascinates me because it’s a feeling that by its nature involves another person. You can be sad on your own, or happy on your own, or angry or whatever, all on your own, but you can’t desire on your own. Your desire needs to have an object. So, the introduction of the object then creates a kind of tricky relationship between the desirer and the desired, whatever that relationship might be. Is it a relationship of dependence, is it a relationship of antipathy? So, it’s just the introduction of that other aspect that makes the feeling interesting for me as a novelist. I’m not so interested in feelings that people go through on their own. So, I think that maybe that’s why desire and love interest me so much.

I watched this video that you did for Louisiana Channel, and you spoke a lot about the idea of how we can’t be independent in a capitalist society. I was wondering if you could talk a bit about how that connects to intimacy for you, or if that makes it interesting to explore intimacy?

Yeah, I mean, that’s the thing, I’m aware that I might be to some extent just rationalizing my own impulses, because I’m not interested in writing about solitude, and I’m not interested in writing about characters who sort of navigate the world in an independent way. And then the way that I rationalize that is obviously by saying that I don’t really believe in those things conceptually. So, I don’t know which comes first necessarily, the philosophy or the instinct [laughs].

But I definitely do have a strong reaction against the predominant discourse of independence. For me, I came at that through a feminist angle, so my development of my political consciousness was really organized around gender, and I’m still trying, obviously, to organize my thoughts around gender now, and also to incorporate other frames of thinking. But the way that I started thinking about gender politics was organized around female independence, so the idea that women should be independent from men, but also from one another and from social structures, and that empowerment was about personal agency and decision-making. And I guess I just increasingly became critical of that attitude. I now feel like there is absolutely nothing independent about the way that we live our lives. What we have managed to accomplish is a sense of independence because we no longer have to see the people who are doing all the work that sustains our existences, because they’re very far away from us in many cases. Or because their work is concealed through other social structures. And so, I just feel like an almost repulsive reaction against the idea that we can be independent when actually we’re living off the labour of others and just pretending to ourselves that those people don’t exist because we don’t have to look them in the eyes.

So, I want to be conscious of that, and then within that, I guess, to take that critique into our personal lives and to negotiate the idea of independence from others in that situation as well. So, the idea of moving independently through our personal lives kind of horrifies me and again, I know that that’s a personal instinct. That’s like me saying, "the idea doesn’t appeal to me," and then I can retroactively apply whatever ideological justification for it, but it’s just something that I don’t like the idea of.

Of course, I’m not saying everyone should do monogamous pair-bonding for their lives and raise nuclear families, I don’t believe that. I do believe that in our personal lives, we end up, whether we like it or not, deeply entwined with other people. And so, I’m interested in how we negotiate those relationships, because they are a fact of how we organize our society, and because they’re fascinating for me. I’m not interested in pursuing the idea that we should have, or could have, independence from other people, either in our intimate lives or in a situation within a network of economic exchange.

You’ve described intimacy as a “loss of self,” and I found that phrasing interesting, because I think there’s an appealing element of that, but also a very devastating and terrifying element of that.

Yeeeeeah. [laughs]

Do you think that loss, good or bad, is something that is unique to being young?

No, I don’t think it is. I think the loss of self, it’s something that, really, the more I explore—I have no academic background in philosophy at all, or philosophy of religions—but the more that I put tendrils out into those areas and do a bit of superficial reading, the more I think the theme of loss of self or ego-death is an extremely common feature of most serious developed philosophies and theologies. It seems like most societies have evolved a concept of the loss of self, or the giving away of self, or selflessness. Certainly, very central in Christian thought, in Buddhist thought as well. So, I think there’s something to it. There’s a reason why we keep returning to this idea philosophically across societies and in different cultural circumstances. And I think one of the ways that we experience it most readily, now, in our current cultural setup, is through intimacy with others. That opens up the possibility that we are giving away our sense of self or putting our own best interests behind the best interests of another person. It’s not something that in an ambitious, capitalist society we do very often. We’re generally encouraged to follow our own best interests all the time. But I think when people have children, that’s one big example of when they tend to put somebody else’s interest before their own. And often I think mutually preoccupied lovers, also, would be more interested in what’s happening for the other person than for themselves. And so, I guess that fascinates me, because it runs counter to the logic of the market or whatever you want to say. But also because it’s something that’s, it seems to me, philosophically substantial. The idea of giving up your self. And obviously as a novelist being attentive to how painful and disorientating that is, as well as the potential for joy and for some kind of profound experience, but also how scary it is. And scary not only because it’s just intrinsically scary, but because it runs so counter to all our assumptions about how life should be lived now, that we should always be looking after ourselves and looking after our own needs and policing our own boundaries. That to do the radical opposite of that feels wrong. And I’m interested in that wrongness. So, yeah, being attentive to both possibilities. And I guess also trying to be fairly value-neutral in the way that I write as a novelist. Trying not to say whether the relationships that I depict are healthy or toxic or whatever. I’m not really interested in those value judgements. I think if I wanted to make those I wouldn’t be writing a novel. The novel, for me, is just about observing how they play out, and saying, "Well, I don’t know. This is how it happened."

That fear of surrender felt, to me, like the great tragedy of the Connell-Marianne dynamic. As I was reading, I just wanted to be like, "It’s okay! Just be together, you’ll be fine!"

Yeah! But they didn’t think they would be fine. And for Connell particularly. Marianne seems, I think, at various points in the novel, ready to give a lot. Connell was not ready to give very much. In the beginning of the book he was ready to give, like, almost nothing. [laughs] Or what felt to him like a lot within very confined boundaries. And by the end maybe he’s learning to give a little bit more of himself. And I think there are reasons why it’s more difficult for him than for her. And one of them may be gender. Like I think maybe men are socialized to fear loss of self more than women are, because women from such a young age are groomed for motherhood, and they’re sort of ready to think, "There will be a time in my life when I’m taking second, or third, or fourth place to the other people in my life." I don’t know that men are socialized to get ready for that in the same way. So maybe there’s a sense in which, because of their different gender roles…but I’m sure there are individual reasons as well. But definitely I think in that circumstance, Marianne was ready, was almost preternaturally ready, to give a whole lot of herself, and Connell was scared by that, and scared by accepting what she was ready to give him and scared by doing the same thing in return.

I wanted to talk a little bit about your activism and the writing you’ve done—what role does that play in your life right now?

I mean, I don’t really think of myself as an activist. I’m certainly someone who has strong convictions. [laughs] And I talk about those very readily because I don’t see any reason not to do that, like, to be straightforward and honest about what I believe. I’m certainly not writing a novel then pretending, "Oh, I have no opinions." I have opinions, and I’m fairly ready to stand by them and defend them. And obviously to be challenged and to accept counterarguments and whatever, I think that’s all part of normal life. But I don’t really think of myself as an activist as such.

In my normal life, completely away from my work, I do normal stuff like going to rallies, that I always did, going to marches and stuff like that. And that hasn’t really changed except that I’m a lot busier now, and not so often at home. But other than that, it’s basically the same. But in terms of using my position as a quasi-public figure, bringing that into my activism or using that as a platform for activism, I haven’t really done that almost at all. I wrote a little bit about the abortion referendum, and I guess I did that because it was a situation where I felt, "Okay, I have a little bit to add on this. There’s something that I can maybe offer here, that I haven’t seen necessarily offered in the rest of the discourse." It’s a little grain of something, but it might be helpful to the general public conversation that we’re having. There are very few issues where I feel like I can help the public conversation. Like really few. A lot of times my opinions I’ve just taken from something I’ve read, and thought, "Wow, that’s so smart." [laughs] And then I’m like, instead of just rewriting that, why don’t I just tell people to read the original piece that gave me the good idea? So I guess I feel like there are people who have lived experiences that are more relevant, who are speaking from a position of more relevance, there are people who are just smarter and more sophisticated political thinkers than I am, who are more engaged in those forms of discourse, and so I don’t think I have a whole lot that I can do, beyond what I do as just an ordinary person, which is show up and do things like that. But that’s not to say that I’ll never…like with the case of the abortion referendum, there may arise specific circumstances in which I feel like, "I’m maybe someone who could be a little bit helpful on this one." But I think the circumstances in which I can be helpful are very limited. So, I try, when I can, to direct people to work that’s being done by other people and say, "This is amazing, you should read it or you should engage with it" or whatever it is. But I don’t feel like I’m necessarily a useful participant in a lot of those conversations.

In the Louisiana Channel video, you talk about the role of literature, and how its role in the economy might compromise its ability to speak truth to power. What role do you see literature playing in shaping political ideas and challenging ways of thinking, whether positively or negatively, and what is its potential?

I’m very skeptical of its potential in that way. This has been a debate throughout the twentieth century—socialist writers and critics obviously argued about the extent to which aesthetic forms, like the novel or like plays, forms of writing other than polemic, can intervene helpfully in political discourse and how they should do that, and what is a socialist novel? And what is a socialist play? And you have writers like Brecht or whatever who manage to answer that case for themselves, but not necessarily provide an answer that works in general. I’m just deeply skeptical because of the ease with which the novel is accommodated by the system of profit-driven publishing. If the book is turning a profit for shareholders, then the book cannot meaningfully be critiquing the system by which that profit is turned. It can offer the critique, but clearly the critique is capable of being accommodated, because the very presence of the book in the market tells us that. So, is it important to keep offering the critique anyway? Maybe? I don’t intend to stop doing it, because it would just be dishonest to stop, because it’s what I believe. But I also want to be appropriately skeptical of the value of that. And not pat myself on the back for including a paragraph in the book where I suggest that that’s the system, that that’s going on, and that the book contains the critique. [laughs] Okay, it contains the critique, but it is also contained by the system, you know, so. I’m skeptical of it.

But I also think that there have to be parts of life that are not…I don’t think anything is completely separate from politics, I think everything we do is captured by one system or another, we’re never totally free of it. But I also think there have to be parts of our lives that make it worth going on with the struggle. And obviously one big part of that is our intimate lives, and that’s what I write about. I think that our personal relationships with other people give us a reason to keep living. And I think for a lot of people, or let’s say for a small number of people, the novel is another reason to keep going, to keep feeling like the struggle is actually worth engaging in, like there’s something worth protecting about human civilization. And for some people that’s the novel. And for other people that’s like, sports or other forms of the arts. There are loads of other things that are of course part of these broad political systems but that bring us a joy or a pleasure that we can salvage that isn’t totally just transactional in its nature. And I think that the novel is one of those things, maybe. That’s obviously not to say it’s fenced off from political concerns, but that there’s maybe something in it that transcends the transaction of simply paying for a book and owning it as a commodity. I would hope so.

I also wanted to talk to you about literary communities, because there’s that wonderful scene in the book, where Connell attends a literary reading…

And he’s like, "What is this?" [laughs]

"What is happening?" [laughs] and the artifice and the privilege of it really comes through. I was wondering if you can talk a little bit about the harm that those communities might do, but also if you see any value in them?

Well, I think, the thing about that scene is, Connell is really suffering from clinical depression at this point, he’s deeply depressed. And he goes to this reading, and as you say, he’s really alienated by what he sees there, it feels so artificial, it feels like the whole art form has been completely captured by the elitist institution, and that people are engaging in it merely as a way of performing their participation in an elite cultural activity. And that appalls Connell—he’s from a working class background, for one thing, so he feels shut out from it, but he also is just someone who’s critical of those kinds of activities, and so it just doesn’t appeal to him. But the writer he meets is actually kind of nice to him! And, again, I wasn’t trying to give a parable there, but I just thought, that rang true to me. That he went along, he thought the reading was kinda bad, the way the reading was structured was borderline tasteless, and he felt very alienated, but the person who wrote the book did so in a sincere way and actually seemed to be a thinking, feeling person, and like, cared. And wasn’t cynical. And Connell left feeling like, "Okay, yeah, I don’t know." Because the way that he felt about the reading was still true, it was an elitist cultural activity, but on the other hand, people who write books, a lot of the time if not all of the time, are sincerely trying to do something good. They’re sincerely trying to find something true or insightful about the human condition or the conditions of our cultural world. And that’s a meaningful thing to do. And they’re sincerely striving to do something meaningful, and obviously they don’t always accomplish it, sometimes they write a book that’s not that great, and the reading’s bad. But the person behind it is sincere, and the cultural activity is meaningful, and we’re all striving in the same direction. So, I think Connell came away from that confused, that there’s a great extent to which artistic endeavor has been captured by commodification and elitist academia, but there’s also some extent to which it’s still worth engaging with because it brings us joy and because artistic effort is still sincere, and it’s worth going on with. It was obviously coloured by the frame of mind that he was in at the time.

But my experience of literary communities, and this is speaking from a position of enormous privilege because I’ve been really lucky, lucky, lucky all the way through, with my first book and my second book, everything has gone kind of right for me, so speaking from that position, which is a very rarefied one, my experience has been that like, other writers have been enormously welcoming and supportive, and I think there’s a strong sense, the way that I’ve experienced it, and again, not to speak for other people, but that we’re all kind of in it together and that the industry feels very random, and you never know what’s going to happen, which book will be successful and which won’t, but that as writers, we’re all doing the same job, and trying to grapple with the same questions, sometimes feeling like we did okay, sometimes feeling like, no, that didn’t really work, but it was an experiment, whatever. And so I think there’s a value to literary and artistic communities, but we should strive not to be captured by the kinds of commodification that Connell is seeing in that scene.

Are there any efforts happening right now to dismantle that literary gatekeeping or overcome it, or counter it, that you see that you’re finding inspiring?

I’m a very solitary person by nature, and I don’t go out much [laughs] or attend things, unless I have to, and so I feel like, you know, I keep forgetting that I’m now in a position of privilege, and that I have this platform, and that there are actually things I could actively be doing to try and improve literary communities, and to try to open them up. And instead I’m just sitting at home writing my next book, because that’s just what I’m like by disposition. But maybe I need to challenge myself and actually try to do stuff.

I have spent the last year editing a literary magazine in Dublin called The Stinging Fly. And so, we have an open submissions policy, and a big priority for us is publishing work by writers who’ve never been published before, so in that sense I feel very dedicated to openness, and to drawing people into the community, rather than to look after the community as it already exists, kind of thing. One of the previous editors of that magazine, Thomas Morris, the Welsh writer who was living in Ireland, he befriended me when I was in my teens, and encouraged me to keep writing, and introduced me to other aspiring writer friends, and in that totally ramshackle way, we developed a writers' circle and we still all share work with one another. And so, he’s someone that I look to as a really good example of how to build a literary community. To go about it in a completely open, slightly arbitrary kind of way based on wanting to support people who feel left out, and don’t know other writers, and who feel completely at a loss as to how to involve themselves in this community.

I had no idea what the publishing industry even was. How it worked, or where it was, it’s in London, I didn’t know that. [laughs] So all of those things, I had no idea. I grew up in the west of Ireland, my dad fixed phone lines for a living. And my mum, in fairness, worked in the arts, she worked in the local art centre, not in publishing at all. So, I wasn’t someone who could just, like, stride into that world. Of course, I had privileges, I had a college education, I did, but it wasn’t easy for me to navigate that world. And so I really did rely on the kindness of other people, who had read maybe like a couple pages of my work and thought, "Oh, come along to this, I’ll introduce you to some of my friends." And I think maybe there’s an aspect in which Dublin is small enough, and Irish social culture is kind of informal enough that it’s easier to do that there. My experience was, when I was writing Conversations with Friends, if you show up to a book launch in Dublin, the writer who wrote the book is right there, you can just talk to them. It’s small, and everyone, in my instance, again, I won’t speak for other people, was very friendly, and open, so it’s easier to feel in touch with the literary community. I think in cities where there is a publishing industry in which there are lots of people employed and working professionally it may be harder to wander into a book launch and meet the person who wrote the book. So I think, in a way, in Dublin, not that I’m saying we don’t have a long way to go in terms of breaking down barriers, because we do—there are lots of issues left to address in terms of accessibility of the arts in Ireland, loads—but just speaking from my personal path to that, I think there are some ways in which it’s fairly open and welcoming, and we need to work on making it more like that.

I’ve seen you talk about a funding model for the arts in Ireland that you think is working well. What's the situation, and what's the benefit to literary magazines?

Well, I should stress, the arts need more funding in Ireland. I was not praising the current government’s funding structure. What I was saying, I think, is that I do think there’s a focus in Ireland on magazines and journals that publish previously unpublished writers alongside writers who have been published before, and get that work out there, and I think those journals and magazines are read in London. I know nothing about American and Canadian publishing, so I can’t comment, but I think in London and in the UK it’s difficult for first-time writers, unless they’ve been through specific MFA programs or whatever, to just submit work to say Granta and get it published off the bat. I think that’s really hard. Whereas in Ireland, of course it’s competitive, and it’s difficult to get published in these magazines, but we will read your work and give it a fair shout. And, speaking from having been an editor there for a year, I really don’t care whose name is attached to it. If it’s good, it’s getting published. Or if it’s good enough, we can’t obviously publish everything that’s good.

There’s a sense in which, I feel like the way the arts community has organized itself, specifically in the literary world, that’s seen as a priority: finding new writers who’ve never been published before, supporting their work, giving them editorial attention, drawing them in and publishing that work and getting it read. So that’s a big priority, and I think that’s something that has really helped a generation of writers, like me, definitely, and also other writers who’ve emerged as a sort of new wave of Irish writing. A lot of them were published in The Stinging Fly, or other similar magazines like The Moth, Tangerine in Belfast is another great magazine. So, I think the fact that that is a priority is good.

Also, that there are specific grants available to writers who have had maybe like one or two pieces published but have not published books. You can apply to the arts council and just get a little chunk of money, and it’s not a huge amount, but it’s enough to maybe look after rent for a little bit while you just focus on your writing. I got one of those, and that was huge for me. I was still working on Conversations with Friends, I’d published maybe an essay and a story, like, not a whole lot. But they gave me some money and I could do a bit more writing and it meant a lot at that time. So, I do think we need more of that. I’m not saying we have an adequate amount, of course we’re never going to feel we have an adequate amount, we definitely need more [laughs], but it’s important I think that that’s what the model looks like. That it’s not necessarily about funding the artists who are already successful, who represent Ireland abroad. I think it’s much more important to focus on people who have never been published before, who have no idea how to get published, and to make sure that they know that these things exist, that they can apply for these grants, that these magazines are here, and that we’re open, we take submissions. It’s about focusing on that side of things, and I think that’s what Ireland has been relatively good at so far.

Normal People takes place during the Downturn Period. Do you feel that there was an impact of that period on Irish art and culture?

Huge. Yeah, I do. I think it was huge. People talk about this new wave in Irish writing, and it’s funny because it’s difficult, for me anyway, to point to a fallow period in Irish writing, because it seems to me like there’ve always been really interesting books coming out of Ireland. And you have writers like Anne Enright, Colm Tóibín, Sebastian Barry, they’re obviously still publishing now, they were publishing before, are they part of the new wave? Maybe not necessarily, but they’re among our obviously greatest writers and they’re still publishing great work all the time. So, for me I think what the new wave refers to is writing that emerged during the period you’re talking about. And that’s what differentiates it from what came before, that it’s writing almost specifically in response to the particular economic conditions that emerged after 2008. And I would date it back to, there’s a collection of short stories by the writer Kevin Barry, called There Are Little Kingdoms, that came out I think it was 2010 maybe? It was published by The Stinging Fly Press actually, and that book felt very different from what had preceeded it in Irish writing, and it was, I think it’s not controversial to say, hugely influential on the writers that then emerged afterwards, writers like Lisa McInerney, like Colin Barrett, and then in turn obviously those writers were influencing me, and the other writers who were emerging then, so I do think that that 2008, 2010, 2011, those years were seeing a big shift in how Irish society was organized, that’s an objective fact, and then, also in the cultural responses that were emerging.

Are there any books forthcoming from Stinging Fly Press or any stories coming out in the magazine that you’re especially excited about?

The current issue is being guest edited by Danny Denton, the writer from Cork, so I’m excited to read everything, because I’m here and he’s there doing the hard work. So, I’m really excited to read everything that is in there, but I haven’t read any of it yet. And then, there’s a writer called Nicole Flattery, who’s just published a collection of stories with Stinging Fly Press, and also with I think Bloomsbury in the UK, called Show Them A Good Time. It’s an unbelievably good collection of stories. Nicole is a really astonishingly gifted writer. I love reading everything that she writes. She just writes the best sentences out there, I just think her sentences are unbelievably good. So, I’m really excited about her book. It came out, maybe I think, February? End of February? So that’s the Stinging Fly book I’m most excited about.

I wanted to talk about mental health a little bit. I love the way you write about mental health, from the smaller moments, like in Conversations with Friends, where alcoholism is kind of on the edges of it, and then in Normal People obviously, in my reading, I felt mental health was very, very present. Is that a starting point for a character, or is it something that emerges as you write?

I think it emerges in the character. I suppose when I first met these characters, I felt like, they were already fully formed and it was my job to find out what was going on with them. Of course, that’s not actually true, and sometimes I have to remind myself, "You made it up! They did not arrive fully formed. You made it all up!" But I can’t accept that. So, for me, it was like, I met, in Connell’s case, this young man, or teenage boy, and I really think now, looking back, when we meet him, he’s already deeply wracked by social anxiety. He doesn’t have that name for it, necessarily, but he feels so uncomfortable in his own self with regards to what’s perceived as normal. And when he manages to come close to that, he’s feeling okay, and feeling comfortable, like he knows how to navigate his life, and when he feels himself pulling away from what’s normal, he gets very unhappy and sick and upset and not feeling good. And he doesn’t necessarily have the vocabulary to think about that, because who does when they’re 18? And then, as he goes through university and feels further and further away from the social world, just feeling deeply alienated from what he sees around him, he sinks in to this terrible depressive episode, I can’t remember what year of college he’s in, third year I think. And that just felt to me like it was the inevitable result of the factors that I’d introduced, I had this character, I knew how he felt in his school life, I knew how he managed to navigate a very fixed and stable social world, and then I wrenched him out of that, and put him in a very unfixed, very mobile social world, where all the pieces seemed to be moving very quickly. And it just felt like the only way that he could respond to that, particularly when Marianne is gone, ‘cause she’s like his one, even though their relationship is in some ways very unstable, she for him is like a stable presence, and then he goes through this bereavement because of the suicide of his friend from school, who he’s completely fallen away from, drifted away from. It felt like the only way that I could work through that remaining true to who I thought Connell was, was to have him respond in that way. And I mean it was never like I sat down and thought, “I should address the topic of depression,” but I felt like I had to stay true to the character that I had, and I was interested ultimately in following him into that exchange that he has with the counsellor. And again, doing what I described, which is remaining fairly value neutral. Like I wasn’t trying to say counselling is good or bad, that’s not something that interests me in the context of a novel. It’s not a judgement that I feel interested in making. It’s like, here’s what he would have done. Here’s what he did. Here’s how it played out. Was it a good or bad experience? I don’t feel like that’s for me to say. But I wanted to be attentive to the detail, and the strangeness of it for him. It’s something that he probably would not have pursued at an earlier point in his life, no matter how bad he felt. It’s something that became open to him because of the specific situation that he was in, and the fact that it’s free for college students in that specific circumstance. I was interested in how I thought that would play out for him.

One of my friends, actually, asked me to ask you this: she was curious about what you were reading and listening to as you were writing, because she listened to the Connell and Marianne playlists that you made. Was that purely a character exercise or was that actually what you were listening to?

[Laughs] Oh man, I was listening to those! Yeah, yeah. I spent more time making those than I did writing the novel, they were so intricate, and honestly if you listen to them in chronological order, a lot of the plot is in there. [laughs] Go back! ‘Cause they’re good playlists. I flatter myself but they are good. So, I was listening to that, yeah. What else was I listening to? I’m trying to think now. I wrote Conversations and this book kind of close together, so there’s probably some overlap in terms of what I was listening to. I think I was listening to St. Vincent, I’m not sure when that album came out though. And, oh, you remember that Sufjan Stevens album, Carrie & Lowell? Again, I can’t remember when that came out but I think I was listening to that writing this.

And then what was I reading? Not a lot. When I was in the process of actually writing, particularly writing early drafts, working really intensely, writing thousands of words a day, I wasn’t reading a lot. And I find that I really have to use my breaks from writing to read as much as I can, try and read like a book or two a week or whatever, because when I get back into it then, I can’t read. I feel like such a fraud for not being able to read when I’m writing, I feel really bad, because it’s like, am I saying I like my own work more than other books? [laughs] That’s so terrible! But I don’t think that’s what it is, I think it’s just I have to shut off that part of my brain. Maybe it’s just that I love reading so much that it just takes up too much of my mental space and I feel too engaged by it. I would like to think that. And so, I need to kind of distance myself from it in order to get the intense work that I need to do done. So yeah, I was certainly reading a lot in the breaks, while I was writing I wasn’t reading much.

What are you reading on this trip?

I just finished Emmanuel Carrère's book The Kingdom. Oh my god, it’s amazing. Okay, this book blew me away. He’s this French writer, and he has written this book which is partly a memoir of his own fairly short-lived conversion to Christianity, he’s writing it from the perspective of having then lost his faith but still being very engaged in the philosophical underpinnings of the Catholic faith in specific but Christianity generally, and part of the book is like a retelling of the gospel of Luke from the historical perspective of the Luke character, so it’s like, so fascinating. There’s so much history in it, there’s so much theology in it, and then it’s also this very personal look back on a period in his life that he now struggles to understand, like he really believed in the supernatural elements of the faith and now just doesn’t at all. So, it’s a really, really, really fascinating book, and it has reawakened my, in fairness, kind of lifelong interest in the gospels. I’m really fascinated by the character of Jesus, and whenever I go back and read those gospels I’m just compelled by him all over again. I just find him so interesting! So, I’m going back now and reading over the gospels again as well, so that has been my big reading interest while I’ve been on this trip.