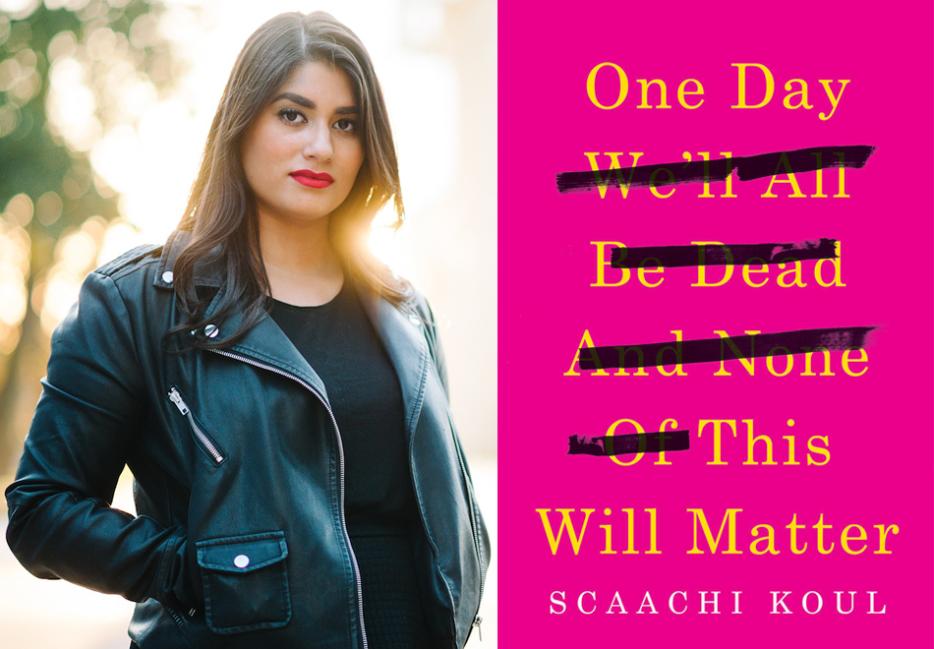

One night, Scaachi Koul lost patience with her Twitter trolls and began lobbing lines from Good Will Hunting at them in response to their tweets, to see if they’d notice. Surprisingly—and yet also not—they failed to. With her first book, One Day We’ll All Be Dead And None Of This Will Matter (Doubleday Canada), Koul nails hardballs into the abyss, one essay at a time. Excepting a few passages, there’s little mention of “them apples.” Instead, the collection traces the (sometimes literal) waxing patterns of her life: from growing up in a mostly white suburb of Calgary, to visiting family in India with her infant niece, known tenderly as Raisin, to reorienting herself after the ruinous actions of a friend.

Koul is the former managing editor of Hazlitt and currently a Culture Writer at BuzzFeed, where she writes perceptive and hilarious essays on the likes of summer camp for adults and the Rock. She is unabashed in discussing how sexism and rape culture pervade our environments, and the corrosive properties of racism and white supremacy. Her writing can cue laughter, illumination and shame in the same moment—a rare gift.

We have been friends since 2013, when I visited the Hazlitt office and promptly demanded that she Google image search Ron Perlman as the original live action Beast, whom I was certain she’d find hot. Recently, we met in a noisy Toronto bistro that Koul assured me would be quiet. I gave her guff, and she gave me guff for giving her guff, which is how we sustain our beautiful relationship.

Naomi Skwarna: So, let’s start from the top. How’s your niece, Raisin?

Scaachi Koul: She turns seven tomorrow.

Does she know about the book? Does she know that she’s in the book?

Mmmhmmm. I went home to Calgary a little while ago and she asked me what it was about and I said it was about her. Then she asked me if she could read it.

It does feel very much about her, or for her, maybe.

I said she could read it when I was dead. Her mom bought her a copy that I signed and will give to her when she’s 700.

Ah yes, I can just imagine her being sixteen and reading the essay about how she was a racist baby.

I hope she enjoys that! And the dumb shit she said when she was five that I’ve recorded forever. I’m sure she’ll appreciate it. She’s known for being really magnanimous. I can’t imagine that’ll get worse as she hits puberty.

Very good. My next question is: you’ve mentioned on several occasions your admiration of the writer and humourist—

Please don’t do that—

David Sedaris—

[Dangerously] Please don’t do that.

Which? Talk in that voice?

Yeah, don’t hold the paper aloft and talk in that voice. That’s a one-two punch I didn’t sign up for.

All right [inaudible grumbling]. ANYWAY—something that has been remarked upon about Sedaris is that the essays often come from a place of pain.

Oh my god, he had a really rough life!

He was so funny about it! Even when he writes about being addicted to crystal meth—

And he thought he was an incredible artist, and he was burning little toy soldiers in the microwave and thought it was great art.

There’s this point when I’m reading him where I’m thinking: someone else could tell this story and it would be brutal and tragic.

You can tell a story that’s unfortunate, and if you can tell it with your lip curled, why not? I don’t really want to hear about your strife if you don’t have any perspective on it. I have a really hard time reading memoirs that are just about raw tragedy. Trauma porn is not interesting to me.

Did you approach certain essays differently to ensure they didn’t express themselves as trauma porn?

The last chapter was really challenging, the one about my dad giving me the silent treatment, "Anyway." I also didn’t have any closure with it, which was difficult. That one sucked and I was upset most of the time while I was writing it. I was miserable while I wrote certain chapters. The hair one was fine. Maybe I’m over those issues to some degree; I think less and less about my body hair the older I get. The shopping one is mostly for laughs. But the stuff with my family was complicated. I was like “I don’t really want these people to read it.” But if they do—okay. It’s honest.

That essay with your dad was somewhat recent, the events that you wrote about.

Yeah, we weren’t speaking when I wrote that. And I had no guarantee that we would eventually start talking. So, what happens if we don’t? I wasn’t ready to write an essay where I say, “well, that’s it,” because I also knew that wasn’t likely.

Something I appreciated about that essay was how you acknowledged a very obscure familial fact, which is that there can be severance without a precise making-up—

And there wasn’t.

It’s still there for both of you but you’ve also somehow moved past it. That was the thing that really touched me, the quiet reconciliation.

It involved both of us swallowing things. I think I swallowed more than he did. I’m younger, I’m spry. But at the time I had no idea, and I was sad all the time. When I finished the essay I remember thinking “I don’t really like this one that much, it’s not funny.” But I was still [experiencing] it, so there was nothing for me to find funny. It is the least ha-ha of the collection.

It also feels the most present.

It is the most recent one. The India chapters, the first drafts also weren’t funny because I really had a hard time on that trip. So when you come back and you’re trying to write it, you’re like, “This trip was not funny. I did not have a good time and I’m mad about it.”

Yeah, and you didn’t even write about the best McDonald’s sandwich you ever had.

I should’ve mentioned it. At the airport in New Delhi, I ate the Indi-McSpicy, which is a chicken sandwich at McDonald’s, and it is the hottest thing I’ve ever eaten. I got through two weeks in India without getting sick, and then the whole plane ride back I was pooping my butt off. I was so sick. [Nostalgically] My only regret was that I didn’t eat two of them, because they were so good.

Something about your writing, the essays in the book and then also the ones that you have published elsewhere, they often involve you selecting something that you will then have to endure.

Hmm.

Is that something that you’re aware of? And if so, how do these things attract you?

I’m guessing you’re talking about the summer camp story I wrote for BuzzFeed Reader? What else have I endured? No I mean, I guess you’re right. Even spiritually. Well, okay. I don’t ... enjoy things naturally. I’m uncomfortable when things are going well. So it’s difficult for me to do stuff, because if it’s going well then that means I’m going to die. But if it’s going horribly, that means I’m not having a good time. I can’t win.

I think you have a real capacity for joy!

The things that I’m forcing myself to do are the things I’ve been told, historically, are good for you. So with the summer camp story as an example: I don’t make friends very easily, because I’m mean. Lots of people would agree—I’m a challenging person. And I don’t engage with people like a normal person, and I know that. So I’m trying to morph into something that will fit. But it won’t, and I’m okay with that. I don’t stay up night thinking about “what does it mean?!”

[The server approaches as if to take away Naomi’s plate, which contains several fry shards.]

[Alarmed] We’re still working on this!

[Server retreats.]

By the way, eat some more of these tiny little guys.

Li'l nubs.

Yes, those nubs are for you.

I’m eating your nubs. When I was younger, my mom would tell me to be nice. I’d say things not knowing they were mean. I just was not conditioned in that way as a kid. Now as an adult, I’m like “maybe fight against your instincts.” Because my instincts are mean! I was mean in high school, and I didn’t know at the time that I was mean. I thought that everyone was being mean to me!

When you say mean, though, were you just defending yourself?

No, I was a bully. I think in some cases I probably was being defensive. I grew up in a town where I felt very separate, and that’s, like, half the book. But I also have the capacity to recognize that I think sometimes I was just a shithead. There are people I would apologize to if I were a stronger person. But I’m not, so I’m going to hide from them. The older I get, the more I’m trying to not engage with that [meanness], but sometimes it’s necessary. I’m not aiming to be nice, but I’d like to at least be thoughtful.

How many of us were as children?

Right, and I think that’s what I get caught up with, like when I’m doing a piece that feels like “this is a pain” and I’m not enjoying it. I’m trying to be better at thinking that there’s something about the exercise that’s worth pulling from. The summer camp one was such a weird weekend. I went, and I wanted to be fun. I wanted to be a fun person, but I’m not! I thrive in the dark. Like a weird bug.

You are fun!

I’m not for other fun people. I’m fun if you’re kind of a dour weirdo yourself. You and I get along because you also have a problem, like, that’s unavoidable.

[High, piercing laugh] What’s my problem?

You’re weird!

I’m not that weird! It’s true, you’ve told me this before.

You are. In a very charming way that I like. I’m not friends with shiny, beautiful people, because I don’t really get it—this is such a weird tangent. This interview’s going to be a mess.

Thank god for editing.

Meanness is a complicated thing when you’re a woman. Men aren’t mean if they act like me. Not at all.

I think a man needs to be a real asshole before anyone says anything.

Yeah, he’s got to hit you. Even then, I think people might be like, “What a cad!”

Have you watched Good Will Hunting since the night you replied to Twitter trolls with lines of dialogue from it?

No! I have that fucking movie memorized now.

What’s your favourite li—

"I swallowed a bug." Minnie Driver says it when she’s in the car. Why? Because it’s stupid, and I know the line now, that’s why. [Snickering] That was a good night! I gotta say, of all the dumb things I’ve done on the Internet? That one felt really good.

What was it like working on this book with your editors [Kiara Kent, Martha Kanya-Forstner and Anna deVries]? How collaborative was the process?

Well, Kiara had a really good eye for telling when I was lying.

Can you think of an example where she wouldn’t let you?

There were two that Kiara had to do a lot of work on. The first one was “A Good Egg,” which features our dear friend [CBC technology reporter] Matthew Braga.

He’s no friend of mine!

Sorry, your nemesis, and my adopted son Matthew “Baby” Braga. Initially when I’d written that essay, it was skating over top what I was mad about—the loss portion [and the story about my violent then-friend Jeff], which was really difficult to talk about. When she got the first draft, she was like, “Yeah ... but.” There was a lot of that, a lot of, “yeah ... buts”: “I’m sure this is a part of the story, but you’re giving me like thirty percent.” I think that was true of “Anyway” for sure, when things weren’t really going well. It felt like something I wanted to write about, but I just didn’t have the tools, maybe, or I just wasn’t getting there. So there was a lot of talking about giving an audience closure without having any closure myself. Somehow.

Yeah, not faking it just because it’s the end of the book.

Exactly. And I think the initial draft was a lie, where I was like, “Everything is fine, don’t worry about it.” And then after that, I wrote another one where there was no closure around “life is hell, and then you die,” which also isn’t right. Many of the essays don’t really end, right? Like, I’m going to go back to India again, and I’m going to have to watch another wedding. My family’s not dead. My dad’s still difficult; my mom’s still like this. How much closure can I give you? There’s a lot of balancing between giving someone an answer and recognizing that I don’t really have one. Kiara was really good at figuring out where that line was.

It’s interesting that you mentioned “A Good Egg,” and the sense of loss. That essay, I felt like I was holding my breath throughout.

Writing that one felt like a risk the whole time. The feeling that if you do something risky, say, if I’m riding my bike, and I’m being an asshole and I run a red light because I think I can make it? The feeling of being between cross-streets, where you’re like, “I’m not sure I’m going to get through this one. This might’ve been stupid.” That was the feeling for the entire duration of writing that essay.

That essay felt like it was about grief.

It was about grief. There was a huge grieving process. [Jeff] was my buddy, so I lost my friend. Then I lost all of my other friends in really quick order. And then I also lost a piece of privacy, because people knew, or they didn’t know, or they knew something. I lost privacy because then I had people asking me what had occurred, and I was still lying for him, so I wasn’t really clear. I just kept losing things.

And it doesn’t seem like you were able to find much compassion in your immediate community.

If you just heard about this guy who knocked me around, oh well. That doesn’t mean anything without context. So I wanted that essay to read like you were me, and you knew something was coming. The story started when I met Jeff, when Braga and I were babysitting him [when he was drinking] and all that. And then when it happens, there’s still half the essay to go, because then it’s me picking up pieces—rebuilding and trying to make sense of all those people who vanished.

It’s so tempting to get stuck in the moment of injury.

And so often the moment of injury is the only thing that people want to read. So if I only give you the moment of injury then you might not pay attention to the rest of it. And quite frankly, the second half of that essay is more important than the entirety of the piece, because the second half is rebuilding. Nobody was asking me how I was doing. And the few women I was sure knew—they sided with him. Because he was fun. He was really fun.

Jesus, that’s chilling.

Inevitably, and this is not a reaction that I would condone, or that I would hope to do again consciously, but my reaction was extra-aggressive, because I didn’t have any other recourse. You’re just mad. We were just talking about how the gendered expressions of meanness are received so differently—people talk about this related to someone like Mel Gibson, or Casey Affleck. Male aggression and violence—whether it’s sexual or otherwise—is so quickly forgotten and apologized for, especially if they come out smiling afterwards, unashamed. So as a form of protection, [women] end up angry, and then people, both women and men wonder “why’s she so mad? What’s eating her?”

[Server nervously delivers coffee to the table, then flees.]

Besides writing, and besides being a ... [whispers] literary darling—

I will divorce you.

A darling of—

It sounds like an illness.

A bon vivant! She just dropped her spoon into her cappuccino with disgust. This is a verbal note for myself. Okay, but really, what do you like that isn’t writing—

I hate this question, because [shrilly] I don’t have hobbies!

[Shriller yet] I’m not asking you for hobbies! Listen to me!

What do I like to do? I like watching trash TV.

No, listen to me, LISTEN TO ME.

Okay, I’m sorry.

I want to know ... when things make your heart feel kind of full and good, what those things are. It doesn’t have to be hobbies. Like, Raisin, your cat, all that shit. You like dresses—

[Laughs]

You like having shiny hair—

[Continuing to wail with laughter] I like watching movies on planes, because they make me cry, and I don’t often have the ability. There’s a study, when you watch a movie on a plane, something happens with your hormones because of the high altitudes. It makes you more likely to weep. I like crying on planes. I like wine. I like falling asleep with the TV on. That’s one of my favourites. I like enamel pins, and rings—especially old jewelry. I don’t really like diamonds. I don’t get it, I don’t understand that pull. I love flossing.

Here’s something I know that you really like—

Is it you?

You tolerate me. Sometimes there’s a flare of affection.

I throw you a bone every so often. What is it?

You like buying inexpensive glasses on the Internet!

I do love hoarding glasses. I found another website called Polette, they’re $29! It’s going to be a real problem.

How many pairs of glasses do you have?

Twelve? That I can wear. Some have an old prescription, so I donate those.

Oh my god, that’s so kind of you—

Yes, as opposed to throwing them into the street and stomping on them.

You’re a philanthropist.

Yeah. You know what makes my heart sing? Donating old glasses.

Do you ever imagine a baby wearing your big red plastic glasses? How cute is that?

Yes, I imagine running into a child wearing my old glasses. [Scathing] That’s my dream.