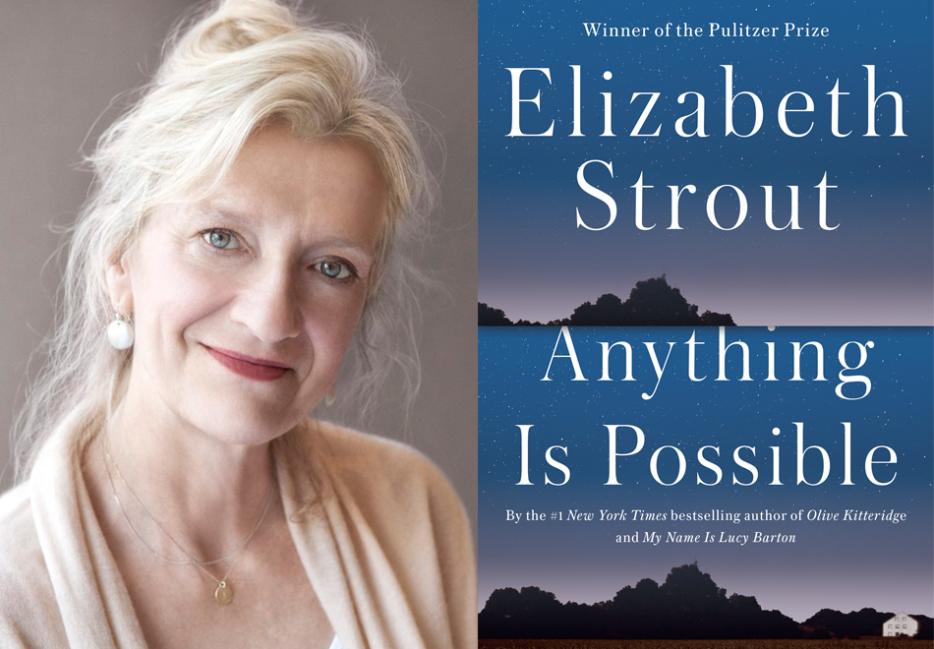

In Anything is Possible (Random House), the sixth and most recent novel by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Elizabeth Strout, the residents of Amgash, Illinois, clash, collide, pass judgment and fall in love with one another. Though the stories interconnect, every chapter focuses on a different character. Dottie Blaine, the owner of a bed and breakfast, becomes a quiet observer of the subtle anxieties and humiliations of one of her guests. Pete Barton prepares for the homecoming of his sister, celebrated novelist Lucy Barton, and suddenly becomes painfully aware of how his humble, dusty life must look through Lucy’s eyes.

That last name will be familiar to fans of Elizabeth Strout. In early 2016, she published My Name is Lucy Barton, a novel narrated by the astute eponymous character while she recovers from surgery in the hospital. Fragmented and poignant, Lucy Barton reflects on her career as a writer, shifting identity as an artist, complicated relationship with her abusive but devoted mother, and the stark contrasts between her poor small town upbringing and current life in the city. My Name is Lucy Barton becomes a recurring motif in Anything is Possible; her success as a writer is in the background to the others’ stories, and the residents of Amgash both resent and admire her for getting out.

Strout is as thoughtful a writer as she is a speaker. She takes her time answering questions and doesn’t waste words, meticulously engaging with her characters and their worlds as if they are as real as any of us.

Anna Fitzpatrick: It's a unique conceit, to have Lucy Barton’s book, and then have a second book where they're all talking about the first book. Her memoir that they read in Anything is Possible, was that intended to be My Name is Lucy Barton?

Elizabeth Strout: Yes, it was.

So it exists in the universe?

Exactly. I had originally conceived of the entire project as one book. I thought, "I'll write My Name is Lucy Barton and then I'll have Lucy write these stories about her childhood." In the end, I thought, no, because her voice is so distinct. I didn't want the reader to turn the page and go into a third person narrative. It just didn't seem right to me. And then I thought, forget it. She didn't write the stories. I wrote the stories.

There would have been certain limitations, if Lucy was the writer behind Anything is Possible. It would have been her interpretation of these characters.

Exactly, so I let that go. But that was my original concept.

So did you write them at the same time?

I wrote a lot of Anything is Possible at the same time that I was writing My Name is Lucy Barton. I would skip over and write scenes of Mississippi Mary or the Pretty Nicely girls.

A lot of the book is impressionistic; chapters will contradict or challenge the assumptions of characters from previous chapters. How honest do you think a memoir can be, in that regard?

I think Lucy Barton was trying to be as honest as she could be. That's why I kept having her qualify her statements. She would say, "Well, I think that's what my mother said." Because I wanted her to be as reliable a narrator as possible, and she understood that writing memoir meant that she could only think that's what she remembered. So, I'm not sure.

She's reliable in the way she's unreliable.

Yeah.

The story jumps around in time a lot. You have this anti-spoiler approach to writing. Like, in Olive Kitteridge, where you'll flash two decades into the future for a few pages and then goes back to where you left off. So it's not really about the plot.

I'm not particularly interested in plot, and I never have been. I don't write with plot in mind. But I write with some change in mind. There'll be a change from the beginning of the story to the end of the story. I figure that out as I go along.

Do you care about plot when you read other writers?

No.

What writers do you like?

I like Elena Ferrante. I liked her books a lot. I have loved Alice Munro and William Trevor. I think those have been my bookends. They're just so wonderful in their own ways. Alice Munro has so much authority on the page, and William Trevor can just flip a sentence so gently and gorgeously. I love Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Philip Roth and John Updike and those American landmarks. I love Virginia Woolf, and the Russians. Tolstoy and Chekhov and Turgenev and Pushkin.

Was there a freedom, in writing Lucy Barton, because you could have characters react to it? Even within her book, she brings her work to a writing workshop, and the teacher flat-out says, "This is what the book is about."

There was. I wrote that scene—I don't write anything from beginning to end. I write these different scenes and see how they work together. I had written [writing teacher] Sarah Payne a number of times before I realized she would even be a writer. I thought, "Oh, this all works together. We'll have Lucy look up to her and go to her." And when I realized I could have Sarah Payne tell the reader what the book is about without Lucy having to tell the reader what the book is about. When Sarah says, "This is a book about a mother who stayed in a marriage because at that time everybody did, except for these different people who didn't. She's happily recounting all the bad things to these women that didn't stay in their marriages." Then I realized, oh, this is helpful.

How did you first conceive of Sarah Payne, if not as a writer?

You know, the first scene I wrote with her was just somebody Lucy met in a clothing store. They had a nice little exchange. Then I thought, okay, let's go back and make this something.

There's that line in the other book, where Angelina's husband tells her, "You're in a love affair with your mother." And that's kind of a lot of the book, these passionate relationships that aren't romances, but with family members.

Exactly. I wanted, not that it matters at all, but I wanted Anything is Possible to almost be like a hall of mirrors that reverberated with My Name is Lucy Barton. Like Charlie Macauley, the Vietnam vet. He's a reverberation of Lucy's father in the sense that these two men were damaged forever by war, so there's that. Then there's other little things I wanted to reverberate.

I saw a lot of parallels between Patty and Vicky, the way they stand separate from their siblings, but Patty really responds to Lucy's work whereas Vicky has this coldness.

When Abel Blaine is recalling how Dottie was twelve years old and was told at school, standing in her stained dress, that nobody was too poor to buy sanitary pads, and that reverberated in My Name is Lucy Barton where Vicky was told by her second grade teacher that nobody was too poor to buy a bar of soap. There were just those little things that I just wanted.

Theme and variation.

Yeah!

Do you consider yourself a political person?

I've always believed that phrase, "the personal is political." If I'm writing about anybody, then it's a political statement in my way of thinking.

Obviously you started this a while ago, but now every week the New York Times has a profile on small-town white working-class communities.

It's interesting, I was just a little ahead of that game. I do think my work is political. It has to be. Anybody who is recording the human experience is recording something political.

Abel [a character from the last chapter of Anything is Possible, who has a strange encounter with an actor from a community production of A Christmas Carol] is a Republican, but he's really insistent on telling everyone that he pays his taxes, and he's not going to cheat on them.

It was funny because I realized, Abel Blaine has gone from eating in dumpsters to marrying the boss's daughter, which we know from My Name is Lucy Barton. The mother tells Lucy he marries the boss’s daughter, and in fact he did. So when Scrooge says, "Oh, you married you way up," Abel is embarrassed. I think he was in love with his wife when he married her, but he did marry into this position of power, of changing from his class dramatically just as Lucy did. Thinking about him I realized, okay, he will be a conservative, and he will be a Republican, but he'll have this fundamental decency in him, which it used to be Republicans did. There are men like Abel Blaine who believed, I'm not going to cheat on my taxes. That's who he is, and he says that he's been successful in business, even though he married into money, he's been successful because people have been known to trust him, and trust in business is everything. He is, in my mind, a very trustworthy man. Not wanting to skimp on his taxes was a way of showing that.

Would he have voted for Trump?

I really don't know about Abel Blaine. I think Lucy's sister Vicky might have voted for Trump. I don't know if Abel would have. He may not have voted. [Laughs] Except he seems like the type of person who would take it seriously. So I don't know.

You know that saying, the one I think applies to most good fiction, "You can never truly hate someone if you know their story"?

To know all is to forgive all.

I was trying to figure out if there was an exact source for that quote earlier, but when I Googled it, it was attributed to the actress Emma Stone, which doesn't feel even a little bit right. Anyway, it comes through a lot in your books, but there are characters who are still a little bit ambiguous. There's the chapter where the couple is spying on the people who stay in their guest bedroom.

And we don't know that much about [the husband] Jay. So we don't really understand his story. Like, what is it that makes him have to do this? The story's more Linda's story, about what made her stay in the marriage and do that. Jay's behaviour is just so creepy, and I'm perfectly aware of that. But I don't judge him as I write. I don't judge any of my characters as I write, which is so freeing.

How so?

In real life, we are judgmental. We just are. And I think we have to be a little bit to maneuver our way through the world. But when I go to the page, I'm just not at all, so it's just fun in the sense of not having to—my job is just to know my characters as well as I can, and to report on them.

I think it's healthy in real life to be judgmental. To say, "Hey, why is this guy spying on women?" But fiction—

Exactly. And I expect the readers to make their judgments. They should. But I'm just saying, as the creator…

I've heard that you've done stand-up comedy.

Oh god.

Is that true?

Yeah, it is. Many, many years ago.

Because you started writing when you were older…

I started writing when I was four years old.

But you started publishing later.

I had a few stories in small literary magazines in my twenties. I think I even had one in Seventeen or Redbook or something. But I had been writing for so long, and it just wasn't right. It was almost right, but it just wasn't right. And I kept thinking, "What's wrong with this?" In my mind, I thought it must have something to do with honesty, because it always does, I think. The real stuff. I kept thinking, what am I not being honest about? And so I had just moved to New York and I was interested, you know, we would go see stand-up comics and I was just interested in it. I realized we laughed at what was true. So what would happen if I was responsible for making a group of people laugh? What would come out of my mouth? And I thought about it more, and I thought, well, let's give it a try. So I took a class. It was terrifying. Every week somebody else would drop out, and those of us who made it through would have to perform at the Comic Strip in New York. And I did, and it was, it really was one of the most terrifying things I had ever done. But the point is, it was very successful. First of all, they laughed. Thank God.

Did you have friends in the audience?

No. And I didn't let anybody come.

Which is liberating in its own way.

There was nobody I knew that came. Not one soul. But it was a full house. But the point is, I learned as a result of my routine that I had been writing over the course of the semester, that's when I really understood that I was a white woman from New England.

Did it also take going to New York to realize that?

Absolutely. It absolutely did. If I hadn't gotten out of New England, I never would have realized that I was from New England. But being in New York at that point for a number of years, and realizing my jokes were on myself for being so New England.

Like Jerry Seinfeld but, "What's the deal with lobster bisque, am I right?" [Anna laughs for a long time at her own joke.]

I can't even really remember it. But I remember understanding like, Oh. Oh, this is who I am. This is funny. It worked.

A lot of comedy comes from dismantling power. I don't think your books would have worked if you were like, "Hey, look at these small town poor people!"

You have to be there.

There's been a lot of debate about what's okay to joke about, and I think too often it comes down to a question of free speech as opposed to, well, what's funny?

I think comics should get a pass on everything.

Yeah?

I mean, they have to. That's their job, to say the unsayable.

But it's not always funny. "Controversial" is such a big umbrella. Something can be controversial but subversive, and something else can be controversial but reinforce the same old. I think your books are powerful because you have characters in the book who make jokes or make fun of the kids for being poor, or who tease Patty for being fat, "Fatty Patty." But those jokes aren't presented as funny in your books. It's just bullying.

Right.

Do you strive for humour when you write?

I never try to do anything except be emotionally truthful. That's always what I'm trying to do. I think sometimes I am funny, because life is funny at times. But I don't try to be funny.

Do you ever surprise yourself, searching for that emotional truth?

Constantly. Constantly I surprise myself. To my mind, that's a good thing, because if I'm not surprised the reader won't be surprised. If I go in knowing everything, it will not be as interesting to the reader.

What were some of the things you learned, with this one?

Just every story, I never really know where it's going to go. Starting with Tommy Guptill, I didn't quite understand until I had him talking to Pete Barton, that Pete was going to take his father's responsibility for burning those barns down. I didn't even understand that until all of a sudden I thought, "Oh wait, wait, wait. Here we go."

What's it like for you going home? When you see people you know in real life who might have assumptions after reading your books?

The people I know in real life know that this is not my life, but I use every single thing that I've experienced or observed my entire life for my work.

You seem very observant.

Yeah. Exactly. I'm always, always, always watching. People are just so interesting to me, and they've always been more interesting to me than anything else in the world. So I watch. And I listen. Everything. It's just how I live. Every single thing gets absorbed. And then maybe years later it shows up in some story.

When did you start doing that?

Absorbing things?

Yeah.

Oh, I think I was pretty young.

Were you aware you were doing this?

Yeah, I can remember sitting with my mother when we went into town. I'd sit in the car with my mother. She'd see a woman walking by and she'd say, "Oh, that woman's hem has not been fixed for quite a while. I guess she's depressed." It'd just be so small, but I got so interested in that woman, in that I'd be peering at her walking down the sidewalk and I can remember thinking, I wish I could see her home. I wish I could follow her home. I wish I knew if she had pom poms on her shower curtain. That's how curious I was. All my life. Starting as a young kid, I was just so curious about people and their inner lives.

As someone who is so observant of other people, are you conscious of how you present yourself?

Yeah. I mean, it's funny because I almost feel I don't have a self, which is crazy, because obviously I do. But I don't...it's hard to explain. I'm not as conscious of myself as I am of other people.

Are you constantly absorbing other selves?

I think so. I think it also probably had to with my background, which was very isolated. When you're not interacting with other people, I think the self isn't developed in terms of a social self. My self has always been an observing self.

Isolated like, as an introvert, or geographically?

Geographically.

You talk about your mother making these observations. You dedicated Olive Kitteridge to her, and call her the best storyteller you know.

She's a fabulous storyteller. She verbally can tell a story. It's so interesting, because I'll watch her take a strand of the narrative and bubble it over, and always bring it back. She's a natural storyteller. She has very intuitive powers. I think I do too. I'm aware how good her intuition is in terms of telling a story and going for the real thing in a person. She taught writing in high school.

What did you read growing up?

I don't remember reading children's books at all. I think I have a memory of my father reading me a Beatrix Potter story once. At a very young age, I was reading adult books. I remember reading John Updike's Pigeon Feathers when I was six or seven years old, because it was on the coffee table. I read that from beginning to end. I didn't understand it, obviously. But I did understand that being a kid was not where it was at, you know? I realized something was going on with this grownup world.

I think that's true when you're developing a creative sense. You absorb everything and don't really discern what's good. Up until high school, a lot of my favourite books were just titles I had heard adults mention, and then I would go to the used bookstore.

Exactly! And then you'd just absorb all of them. And that's really, really what I did. I would make a list for myself at a young age, starting around twelve or thirteen, I would make lists of books I had heard of, and just read them all. And then we had a set of Hemingways, full complete works. My grandfather had been sold the complete works of Hemingway by some traveling salesman, and so they sat there on the shelf and I went through those at age seventeen from beginning to end.

When was the first time you remember really loving a writer?

I can remember reading To Kill a Mockingbird when I was in the third grade, and that was memorable for me. And then I can remember reading Lolita when I think I was about fifteen, and I loved it. I just loved it. I wept, I thought it was so beautiful.

What did you love about it?

I thought it was a love story. I really saw that book as a love story. That killed me. And then Hemingway's books, it was interesting, because I understood some were not as good as others, but I loved him. I loved his work right away.

Have you read Lolita since? Has your relationship with it changed?

I have. You know, it has changed, but I still cling to that first reading of that because it was so memorable to me. You know, when you get older—there's a freedom in being able to read things when you don't know what the world thinks of them. I remember these friends of mine, their parents were so against Lolita. I just resist all that because it was what it was to me.

I had romantic sensibilities as a teenager, both about life as well as what I thought a being a writer and reader meant. I read books like Romeo & Juliet and Wuthering Heights, and then later you're told, "These aren't actually about being in love! These are about these messed up relationships." But just cause you're in love doesn't mean it's going to be pure and healthy.

You're exactly right. I had the very same experiences with Wuthering Heights.

People say it's not a romance, but it's incredibly romantic.

Incredibly romantic. Incredibly romantic. I couldn't agree with you more.

It's warped and upsetting—

Because it's real life in a certain way.

Obviously when you're fifteen you shouldn't model your real life relationships off it—

But who cares? You're just reading and absorbing this intense situation.