I like going to cemeteries when I travel. For one thing, it's interesting to stumble across famous people's graves. (Two-hit wonder and Austrian darling Falco, whose grave I discovered while in Vienna, is resting under a near life-size portrait printed on clear Plexiglas. He is wearing a cape in the picture. He is likely wearing a cape in the grave.) Mostly, though, travel can be overwhelming and a visit to the graveyard lets my nerves regrow. There is no silence like the silence in a cemetery.

So when I had a few free hours in London two years ago before leaving to go home, I went to Highgate. It almost didn't happen; my friends were too bushed to come along, it looked like rain, and when I read the guidebook I realized that if I'd wanted to go to the cemetery's gorgeous crumbling older half, I should have booked a tour before I even got on the plane. But the newer, eastern side seemed nice enough. Karl Marx was there, the guidebook said. So was George Eliot. And wait—wait. So was Douglas Adams.

This is how I ended up stealing a pen from a dead man.

*

To say that The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy has defined my life might actually be an understatement. I now think of my preteen self as “pop culture echolalic”—I didn't know how to think or make jokes or interact with people, so I faked it by digesting books and plays and regurgitating them in a different order. And if that seems like it’s changed as I've aged, it's only because it's gotten more seamless; I've chopped up the references finer, down to their component elements, so I'm more of a concrete golem than a collage. I rarely call myself a “fan” of anything, just because I'm not a joiner; fandoms, like parties, make me shift nervously and look around for a dog to talk to. But when I was 14, my best friend and I went by “Lunkwill” and “Fook” at summer camp—not because we especially identified with those characters, which are ciphers, but just to establish what world we were part of. I have a Babel fish tattooed on the inside of my left forearm. And there is nothing about myself that I love that isn't secretly Ford Prefect.

I don't typically tell people about the camp nicknames. I talk even less about Adams' most persistent and troublesome legacy for me: he makes me want to write fiction, and not just fiction but funny sci-fi, and not just funny sci-fi but funny sci-fi that will help some other weird preteen pop-culture echolalic navigate the world. I can manage the first two bits, in dribbles, when the plug of anxiety damming up my creative impulses springs an unscheduled leak. That's no surprise; Adams wrote my inner monologue, so of course I can channel him a little. The last one, though—that last one brings me up short. You can't set out to write something that will change lives; it's unrealistic in a way that will break you. But anything else is a disappointment, a failure, a waste—and an embarrassment, to yourself and to your muse. What's the point of writing if you can't be Douglas Adams? And what's the point of trying to be Douglas Adams when you know you'll just be a ridiculous ghost?

*

Adams' grave marker is a plain greenish stone, decorously incised “Douglas Adams, Writer” in letters so clean and shallow that they're difficult to see. I might have missed it, except that there's a ceramic jar in front of the headstone that's jammed full with pencils and pens.

I found a snail shell and put it on top of the headstone, with the other “I was here” rocks, and sat for a moment on the shallow steps that lead past his grave, from the paved thoroughfare up to older and dimmer paths. From this angle, he's got a pretty good view, I thought, and then realized how ridiculous that was: Douglas Adams was a committed atheist who scoffed at the notion of consciousness after death. I am too, which is part of why I've never gone to cemeteries in order to commune with the famous dead, but this felt different. He was here, coded into the entire shape of my life. Sitting by his grave brought that shape into focus, illuminated the ways he'd influenced my personality and my thinking and my secret, shameful, never-to-be-realized ambitions.

I came back on my way out. By this time, rain was falling, or more accurately mist was hovering in a way that made you just as wet. I stood for a moment looking at the pens, and thinking about writing: the magic it requires, which isn't magic at all. Douglas Adams has always described his process as one involving long baths, large meals, and missed deadlines—an act of concerted appetites. I thought of the planet Poghril, whose population had nearly all died of famine before the Heart of Gold, a ship powered by the Infinite Improbability Drive, caused 239,000 fried eggs to materialize on their planet. The last Poghril inhabitant died of cholesterol poisoning. Indulging the appetite can harm you as surely as denying it, if you don't know how to proceed. But denying it forever will kill you for sure.

Look, I said to Douglas. (I didn't say this out loud, even though it was nearly closing time and there was nobody else in the cemetery. Getting emotional at a stranger's grave is one thing; talking to it out loud just felt cheesy.) I'm going to take a pen, because you're dead, and even if you weren't, you'd laugh heartily at the idea that your dead self would miss one. And I'm only going to use that pen to write notes for my fiction, and I'm going to use it every day, and I'm going to try to figure out how to write things. I'm going to try to figure out how to write things that would make you proud, if you weren't dead and you had any clue who I was.

I grabbed one at random. It turned out to be a Westminster Abbey souvenir pen. I laughed. I think he would have laughed at that too.

*

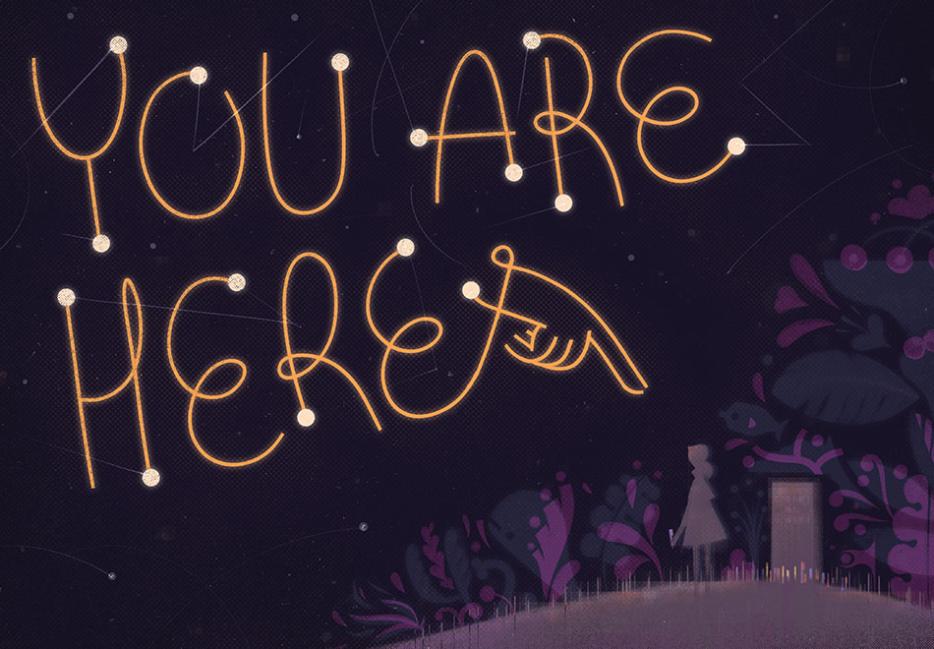

One of Adams' most indelible creations, one of the ones that climbs inside you and makes your understanding of the world both clearer and more absurd, is the Total Perspective Vortex. It’s a metal box just big enough for a person, which, when turned on, contains the entire sickeningly vast universe along with an invisible dot on an invisible dot marked “you are here.” It’s used to annihilate people's minds.

What's the point of writing if you can't be Douglas Adams? And what's the point of trying to be Douglas Adams when you know you'll just be a ridiculous ghost?

I was eight when I discovered the Total Perspective Vortex. At the time, I was profoundly terrified by the concept of infinity—be that death, the universe, or everything. I once nearly passed out in fourth-grade music class because we were singing a song about the planets and I suddenly couldn't cope with the idea of them spinning through all that chilly nothingness. The rest of my memory of The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, that first time, is fuzzy; I didn't really get it, not until I revisited the books when I was twelve. But I remember the Vortex. The Vortex made sense to me. To grasp, even for a second, your true relative importance in the grander scheme, to understand the pure pointlessness of you – this was something I kept tiptoeing towards, even as a kid, and then sensing the yawning void up ahead and panicking. When I read about the Total Perspective Vortex I understood why this is painful, and irresistible, and the only truth.

In the Hitchhiker's Guide radio show, feckless galactic president Zaphod Beeblebrox makes it out of the Vortex only because he's accidentally wandered into a pocket universe that was created just for him. If Douglas Adams walked into the Vortex in my universe, he'd be fine too. He's crucial. He's everywhere. But me? I've always known I'd never survive.

*

I lied to Douglas' grave about the pen.

My intentions were good. For a while I did make time every day, or most days, to make notes and think about fiction and, sometimes, write a bit. I even signed up for a creative writing course after I got back from England, but on the night of the first class, I panicked and couldn't make myself go. I paid the teacher half of the registration fee for the privilege of cowering at home.

Sometimes I avoid advice about writing, and sometimes I read as much of it as I can stand. I know you have to do your morning pages and go bird by bird. You have to try and fail, you have to be derivative and bad for a while until, in theory, you're not. I don't know if this can coexist with writing because books created you, because you were born out of books and want to do the same for someone else.

For me, maybe not. When I look at a bookshelf I see the books that are the scaffolding of my life, and all the other books I loved and all the ones I'll never read, and the ones I'd hate, and the ones still being written and poised to become beloved or fall into obscurity, and the ones that could be written in the future, along with an invisible dot on an invisible dot marked “you are here.”

They say you need to be a reader to be a writer, and that's true. But is it possible to love a book so much it paralyzes you? Is it still inspiring if you read it so hard that it’s burrowed right into your DNA? Or does it become a sacred duty you can't live up to, a burden you can't shift or throw away? Does the book you love so deeply become a disapproving parent who'll never love you back?

I was honest about one thing, at least: I don't use that pen for anything besides fiction. I’m not the type of person who collects memorabilia: I lent my signed Mostly Harmless to a friend in high school and never got it back and never really minded. My copies of most of his books are in shambles, read to shreds. But I'm precious about that pen. It won't be used to write a shopping list while I'm alive. The artifacts of reading are comfortable, disposable; the artifacts of writing are amulets and alchemist's tools.

*

Douglas Adams himself did not like writing. He was famous for hating it. All his large meals and long baths were intended to soothe the fact that the actual work of writing was always a chore. For him, ideas came fluently, and for me they are more arcane, but when it comes to putting words on paper we are brethren in anxiety.

If there's anything that fans of the Hitchhiker's trilogy know it's that in order to fly, you must throw yourself at the ground and miss. And you can't miss on purpose—you have to really fling yourself down, fully expecting to chip a tooth at best, and if you're lucky, something will catch your attention at a crucial moment and you'll simply fail to hit. It's no good trying to miss the ground; it doesn't work that way. It's part luck, and part distractibility, and part trying to do the wrong thing with all your might.

Douglas Adams hated throwing himself at the ground, but he did it, over and over, and he got very, very good at missing. Me, I'm mostly too scared. The ground is hard. It's cold. Dogs pee on it. You look very silly when you end up on it, especially when you put yourself there.

I don't know what, if anything, will make me ready to fall on my face. I hope it's something. I guess it won't be a pen.