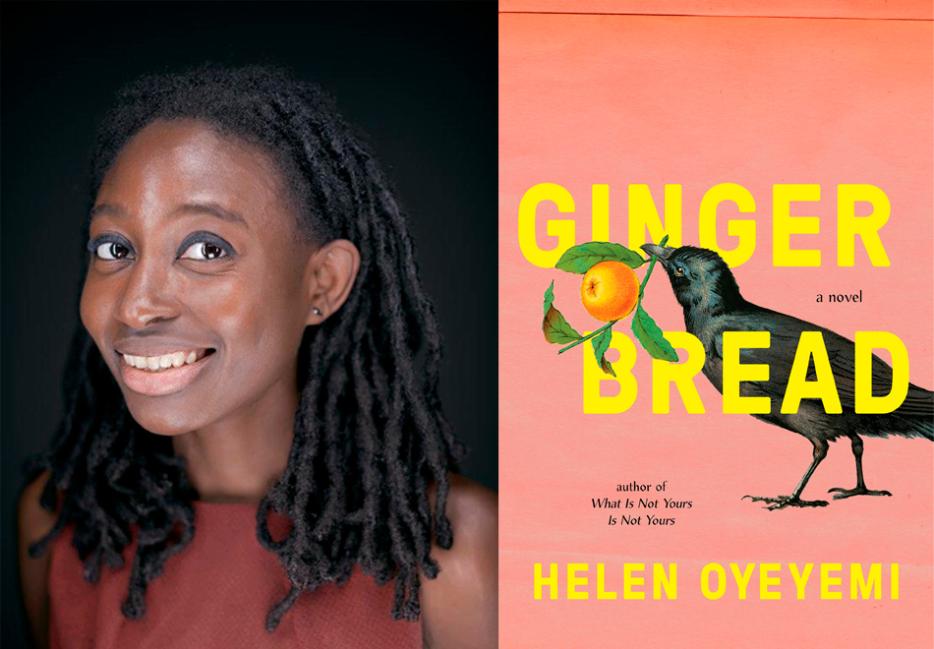

Helen Oyeyemi’s work always holds an element of discovery. She describes books as places she visits, and her writing invites readers to do the same. Whether that place is a locked garden, an ancestral home (or several), or an imagined country, the reader is left with the feeling that they’re being guided through by a hand they can’t see, persistently tugging them left or right or sideways.

There are many places it feels like Oyeyemi’s latest novel, Gingerbread (Hamish Hamilton), could take you, if you were so inclined. Some of those places are physical: the characters in the book cross borders in trunks, live in houses where the rooms occasionally move or the stairs keep out all but the most determined visitors, and sleep in beds watched over by flowering dolls. But the spaces are also internal: There’s the space created by the suspension of reality that comes with a dramatic health incident and the subsequent, if you’re lucky, healing. Or the cavern carved when someone we love disappoints us entirely and we probably should have seen it coming. Or the space between childhood and adulthood, where we begin to understand the bargains we strike to afford growing up.

In each of these places, our reality skews just a little. Gingerbread’s narrative suspends us in Harriet’s tale of her childhood and adolescence while her daughter Perdita recovers from a hospitalization. The reader is allowed into this sojourn from reality, and then, when Perdita is again well, the world tumbles back like Harriet’s signature gingerbread to the floor. First, a few crumbs, and then the whole damn box: family, friends (who Harriet’s not sure about yet—she’s waiting for a sign), meetings and exams and essays and candles that won’t stay lit and houses that might not let you enter. The world keeps going when you remove yourself from it, but like Harriet’s oft-disappearing oldest friend Gretel, your absence is noted.

Haley Cullingham: I wanted to start by talking about place, because I find the way that you write about place so fascinating and, especially in this book, it was such a dominant theme to me. I know you’ve lived in a bunch of different cities, and you travel a fair bit, too. If you’re going somewhere, do you read stories of the place?

Helen Oyeyemi: No. I was so interested that you even said that place came through strongly, because I don’t think about place too much. Place is very abstract. So, I guess my approach to place is, I read books as if they are places. It’s more like going into a book. And so, there isn’t that geographic sense, it’s more abstract and interior. There are details that you can pick out and leave the rest quite vague in certain ways. Which I guess is how I travel, just looking at the things that I’m interested in and the rest is sort of a blur.

What are some of the places that have left the strongest impression on you?

I love Seoul, I try to be there every year, and not just for a few days but weeks. Budapest, I was there for a year and I still think about it a lot. I think about the two cities, and the bridges that connect them, and also the walls that have cannonball marks on them and just the way that the city wears everything that’s happened to it, similar to how you see a shroud and an evening gown, there’s this strange mix of pride in having survived so many things and also this great sadness and melancholy. Where else? Istanbul. I’ve only been there once but I think about that trip a lot.

Do you think you’ll go back?

I think I liked Istanbul so much that I’m worried if I go back it would be disappointing in some way. I say that with most cities, going back, but I’ve started to really love returning. Maybe that’s the thing with Seoul, there’s just more and more city. Or maybe it’s just the way that cities turn over and change so quickly. There’s always something more to see or find out.

When you go back to Seoul, do you revisit a lot, or do you tend to explore new things?

I find new corners. With Seoul, there haven’t been places that I feel I need to go back to, but I have been back to Jeju Island, which kind of makes a bit of a cameo toward the end of Gingerbread, but it was two completely different experiences. The first time I went on my own, and I was completely overwhelmed and absorbed in the best way by how lush Jeju is. It was a tumbling into the sea of impressions. And the second time, I went with a friend. We rode this bike, it was so scary. It was a two-person kind of a bike, kind of a wagon, and my friend was like, “I can do this, I can get us around,” but we were on these coastal paths and I just pictured, like, we were going to fall directly into the water. So, it was precarious and fun and different. [laughs]

Were you both pedaling?

I was just the passenger. I was just wearing this helmet and screaming, which I think she didn’t appreciate. So, the second time was more rambunctious.

When you start thinking about a book, does it start with a character, does it start with a story, does it just start with a feeling of wanting to go somewhere? How does that begin for you?

It’s been different with every book. So, with Boy, Snow, Bird, I was doing the wicked stepmother story, but I was also doing ‘50s America, and so I had to place myself within that, which was actually a delight because I love the films of that era—Hollywood from the ‘30s to the ‘50s is entirely my space. So, it was kind of fun to write in that register and to think in that register. And then for What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours I just had keys, and then I wrote stories about the keys. With Gingerbread, it was much more abstract, because I had this substance that I wanted to interrogate, and place at the centre of a story without making the meaning of it too clear, because that would be boring. I wanted to allude to various things and suggest various things around this concept of gingerbread, and so it was a lot more slippery to write, and also it felt like more of an adventure, which came from not knowing what sort of book it was going to be.

I was wondering if, the way you’ve talked about the keys, if the gingerbread was a similar feeling.

I thought it was going to be but the keys, it was straightforward. Nine keys, nine stories. Gingerbread was… [laughs]

Touching on the food stuff, for you, is there kinship between cooking and creating a story? Are those things that feel connected?

Yes, and the same with consuming the cooking and reading, so I suppose it was all quite densely layered in there. Since I’ve been going around with Gingerbread, hearing people talk about it, and reading the things people write about it, of all of my books, I think this is the one I most want to say: there are lots of things in here. There are lots of ingredients. I’ve become slightly worried when one element is pulled out, and it’s said that the book is about one thing. It’s about all of the things—I’m not saying it’s not about that, but there are so many other things that it is equally about. So many that, in fact, you can’t mention them, which makes it very difficult for anyone who hasn’t read it who’s trying to decide whether to read it.

One of the moments when that struck me the most is that little part where you’re talking about Simon, and the way that he would emotionally manipulate his way into getting more gingerbread. To me at least, I was like, this is such a perfect and wonderfully succinct description of addiction. But the books are always so layered that you just have this moment where it’s perfectly clear, and then it’s like, new thing.

Yeah, so gingerbread is a way to talk about many things, and then, like, if someone says [gasps] you just say, “Oh, it’s just about gingerbread, I’m only talking about gingerbread.” In some way I feel like it’s a female way of telling stories, I feel like feminine stories have always been quite coded in that way, just in case anyone tries to, like, burn me at the stake or something, you can be like, “No, I was just talking about gingerbread.”

It’s just a recipe, it’s fine.

Yeah. So, the codedness, I’m in two minds about the way that it persists into the 21st century. But I don’t think I did it because I was afraid. I think it’s converted into being more on the fun side.

Can you talk a bit more about what you mean when you say you’re not sure how you feel about how it persists in the 21st century?

Yeah, I mean, a way of writing or speaking elusively that, in some ways it’s about fear of being punished for what you have to say or what you think, that persisting, it makes me sad, and it’s maybe part of the reason why I don’t tweet or do things like that, just because I kind of see people having an opinion, and everyone being like [mimes a pile on]. It’s sad that it may still be necessary to use it for those original purposes, but I don’t think that that was what I was doing with Gingerbread. [laughs]

The book made me think a lot about how there’s always that close connection between things we wield as nourishment, and things we wield as weaponry. Was that something you were thinking about?

I don’t know if I can put it properly into words, but the power that you have over someone by feeding them, or not feeding them, as the case may be. But along with getting to eat and offering something to eat, I was also thinking about children earning their keep and not necessarily eating for free, because they have a role that they have to play, and I guess that line of thought turned into the strange interlude with the Gingerbread Girls and having to perform being children for money. It was the ways in which food can become currency. I give you food, you give me affection, and other forms of that same transaction.

I was reading a Bookforum interview you did in 2016, and one of the things you talked about was the idea of being drawn to things that have a certain “faith in storytelling.” And you also used the description of something having “an engine of meaning.” I was wondering if there were any recent stories, whether they’re films or books, that fulfill that for you.

One of my favourite films ever is Celine and Julie Go Boating. It has so much imaginative force that it becomes sort of madcap and misshapen around the edges, and the two characters start forgetting when they first met each other, and it’s as if they have always in fact known each other, since before before the story. A snake eating its own tail. But also, there’s this, not exactly a subplot, but counter-plot, where they themselves enter another story and try to hijack the meaning of that story. It’s that engagement that I recognize as a reader or a film watcher where you participate in a story but you’re not subject to its rules. Like being under a spell, but also casting one yourself at the same time, spell and counterspell. So, anything like that that just becomes very magic and reckless and starts pushing the frames of its own existence out further and further.

Are there any stories that have been created recently that are starting to take on the significance that fairytales have had? That are starting to bleed into consciousness in that same way?

It might be more of a visual thing, even a televisual thing, than a written words thing. Maybe my obsession with Korean drama is part of this, because there’s a certain tone that they take, which I also recognize from the golden age of Hollywood, especially the screwball comedies and the film noir. I think those, fairytales and K-Drama have something in common. They’re stories that don’t really need you to believe them, they’re just saying. But the things that they’re just saying are resonant on all kinds of levels, like, you laugh, and you sort of wince, and you cry, you just have these responses to what seems like an elaborate, or a vocabulary of, it almost seems like psychology archetypes that they’ve arranged for you and circulated so that you see them in a completely new way.

Do you miss some characters from the book more than others?

I miss Perdita. She’s in the story, but she’s like, “Oh well.” I feel like a lot of people become aware that they’re in stories and they’re like, “No, I want out of the story!” or they try to figure out how to game the story so that they can be the main character of the story.

You’ve spoken before about how the Czech version of “Once upon a time” is “There was and there wasn’t.” That, to me, feels like a perfect way to talk about Druhástrana. This may be negated by what you said above about the influence of place, but I was wondering if Prague, where you currently live, had crept in in that way.

I think it has, yeah. I have not tried to keep it out. Like you said, I will say that I’m someone who’s indifferent to place so I’m quite interested in the fact that there’s bits of Czech in there, and I don’t know what’s going to happen with future books. We’ll see. And there’s Druhástrana, which means “other side” but can also mean “other page” in Czech. And so of course, if you had this country that only Czechs know about, it would make sense for it to have a bookish aspect. Druhástrana as an unknown quantity, it’s a little bit like Czechia. I didn’t know anything about it before I moved there. Prague, it’s just so glorious and strange and wonderful, like, “you’ve been here all my life?” It was very strange. It felt hidden, like I said a magic word and there was Prague.

Did you go there knowing you were going to move there?

No, I went for a few days and hated it. It was not a good time to go. It was peak tourist season, the weather was terrible, the food was terrible. But I was with a friend that I love very much, and we would have phone conversations being like, “remember when we went to Prague and it was terrible?” And then a year later I just moved and it was completely different. Or I was completely different.

You’ve talked a bit about watching K-Dramas while you were writing. Was there anything else that you were listening to, or reading while you were working on this that stands out?

There was a lot of the Bill Evans Trio, a little bit of Coltrane as well. And then there was some K-Pop, there was some rap, there’s one song by Big Sean, which I can probably rap off by heart, but I won’t.

In the book, Perdita’s grandmother, Margot, talks about houses that look sensible until you get inside, which made me think of your novel White is for Witching as well. I was wondering why you’re drawn to those spaces?

I don’t know that I’m drawn to them. I mean, part of the house thing was maybe a little bit of a joke, because everyone’s always saying to me, “You’re so interested in houses.” And I’m like, “Am I?” “Haunted houses especially!” and I’m like, “Am I?” [laughs] and so it was kind of fun to have these haunted houses that weren’t haunted.

Do you have a favourite haunted house story?

No. Oh wait, can I go back in time? Obviously The Haunting of Hill House! The thing about The Haunting of Hill House is that because the house is positioned as sentient, you forget that it’s a haunted house story, so that’s why it slipped my mind.

When you’re writing about the gingerbread recipe in the book, you write about the difference between “choking down risk and swallowing it gladly,” and I just thought that was such a lovely way to describe it. I was wondering what inspired that idea?

Honestly, I just ate a lot of gingerbread. I just would eat it, and then write down what I thought whilst eating it. And so, it was just something that came to me. Because I guess I was like, what if this gingerbread was poisonous? Would I continue eating it? Probably.