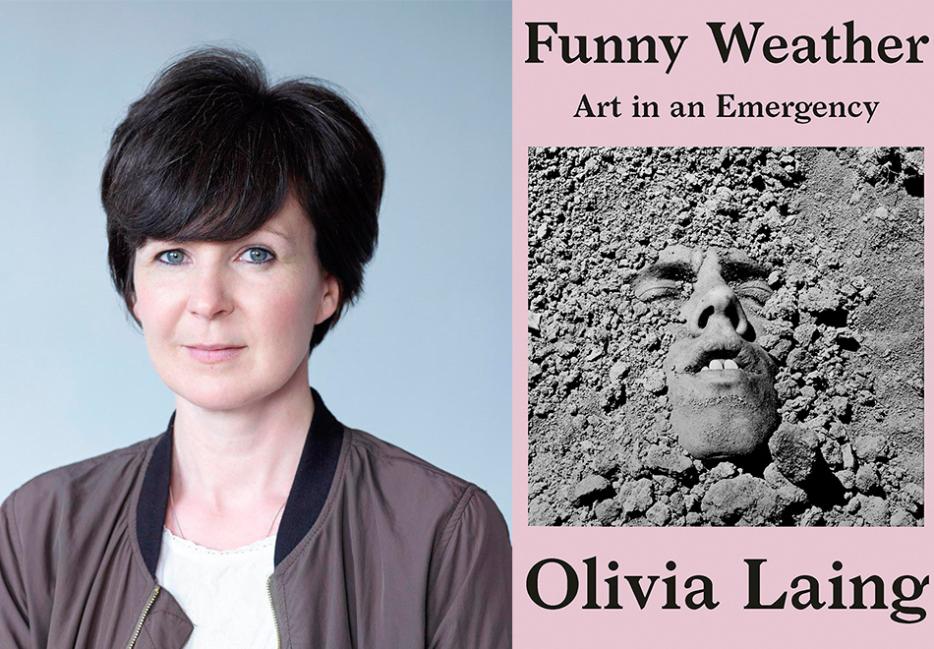

When Olivia Laing was putting together the manuscript for her fifth book, Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency (W.W. Norton & Company), a manifold collection of her columns for art magazine Frieze and original essays, she was imagining the possibilities of art as a soothing balm for an era riddled with gun violence, political turmoil, and the oncoming threat of climate change. That was before the plague. As COVID-19 raged around the globe and rearranged present-day life in a matter of weeks, Funny Weather became a prescient and strangely even more relevant book. Charting the lives of itinerant artists like David Wojnarowicz, Agnes Martin and Arthur Russell, Laing explores the generative power of art through biography. Rather than directly answer the question, “What is the purpose of art in an emergency?,” Laing provides all the tools for the reader to come to their own conclusion—examples of resistance are embedded throughout like the titular character in a Where’s Waldo book. Like much of Laing’s work, Funny Weather functions as an exquisite, erudite fan letter to the artists who have influenced her the most, seeking to present innate truths through the medium of biography.

The quality I most associate with Laing’s writing is a melodic contemplativeness. Her first novel, Crudo, which fictionalized the itchy experience of absorbing bad news online, felt markedly different from her nonfiction work. Crudo was the literary equivalent of picking a scab; urgent, weird, and painful but compelling. Funny Weather is a return to form, holding it’s own against the languid prose of To The River and the somnolent emptiness of The Lonely City. Each sentence is entrancing, intoxicating and rewarding, like taking a dip in an Olympic-sized pool and emerging utterly refreshed. In the chapter memorializing Georgia O’Keeffe, she writes of the artist’s cow-skull portraits, “Bones were beautiful, with their apertures and cavities, their bleached resilience,” a tumbling masterpiece of adjectives and subject.

Laing writes the adult version of I Spy books, lush tableauxs crammed with so many objects the eye doesn’t quite know where to look. But a dedication to combing through the pages is always rewarded with a painstaking view of the exact thingamajig one was searching for. Ultimately, what emerges is a generous portrait of artists not merely functioning but thriving amidst difficult circumstances—and a potential answer to Sheila Heti’s prodigal question, “How Should a Person Be?”

Isabel Slone: The fact that Funny Weather happens to be about how art can soothe in an emergency makes it all the more prescient. How do you think the current social conditions will affect the reading of the book?

Olivia Laing: The sort of conditions that I was writing into five years ago that seemed distressing at the time now seem like, “Wow, that was a nice nostalgic time.” I think people are existing at the moment in conditions of intense anxiety and isolation, and also that they’re thinking about how the world is and how they want it to be in a very open and unguarded way. I wrote this book for times like this, and though I wish we weren’t going through a pandemic I do think the message of art as a tool for clarity and for imagining other possibilities still holds firm.

Has climate change has taken a back seat to other concerns during the pandemic? How do we weigh those concerns equally?

Everything’s taken a backseat during the pandemic, which is understandable. But the thing that gives me hope is that we've been told for years that the kind of drastic changes needed to deal with climate change were impossible, and yet in the space of a few weeks the world has changed utterly. People have found that they can work without flying around the world, and we’ve all had to reconsider things like global supply chains and where our food comes from. I hope that when we emerge from this particular crisis we can pivot and feel energised to face the far greater challenge ahead, which imperils not just human life but the natural world too.

We’re experiencing this time of extreme distress and yet ironically there’s been a lot of suggestion that it’s a good time to do creative work, like we’re all theoretically supposed be writing the next King Lear or whatever. How do you approach maintaining creativity when doing just about anything feels insurmountable? I saw you’ve already filed a draft of your next book.

I was really lucky, timing-wise, in that I was right at the end of Everybody. Five years in, I’ve built up a huge amount of momentum and it’s easier to go to my desk, lock down and spend those hours writing than to do anything else. It’s really a huge luxury to be able to escape day-to-day reality like that. Even though I’m writing about very dark material, it still feels like an escape hatch. As for the pressure around creativity, I think there’s something sadistic about the pressure for people suddenly to be very creative when they’re clearly terrified. People are anxious about themselves and their families, they’re cut off from their support systems. Yes, we have got an unprecedented amount of time and that does feel very freeing in a funny way, but at the same time we’re also under extraordinary pressures. I think most people probably feel the opposite of creative, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Do you usually write two books at a time?

I never used to, but I’ve been working on Everybody, the book about bodies that I’ve just finished, for about five years and it has been very, very difficult. I wrote Crudo as a sort of explosive reaction to it, as a way of expressing some of the fears that confronting violence and the body were bringing up in me. And then I put Funny Weather together at the very beginning of 2019, while I was still slogging away at Everybody. It was really a way of just having something else to do while writing this very difficult, recalcitrant book. My publishers are always saying, “Why are you giving us this? We didn’t ask for it!” I have a history of turning in unexpected books.

Funny Weather feels like the opposite of Crudo, in a way.

I’d say they're a funny sort of pair. Crudo was written in a frenzy, over six weeks, and is basically unedited. I wanted to preserve the raw texture of what seemed at the time like a very disturbing political moment. The idea for Funny Weather came to me about six months after Crudo was published. It struck me that many of the essays I’d written over the years were about art as a force for resistance and repair, and I wanted to put them together and make them available, as a kind of antidote to the fear and anxiety I’d been documenting.

I’d like to ask about your research methods. You always manage to unlodge these incredible historical facts, like the delightful mise en scène where Joseph Cornell and Yayoi Kusama are having a youthful romance and Cornell’s mother finds them kissing in the backyard and dumps a bucket of water on them. Where do these arcane historical tidbits come from?

I spend a huge amount of time in the archives, reading my way around things. Sometimes I’ve read a line or found something so brilliant that I’ve yelped out loud in the library because I’m so excited. That anecdote came from Kusama’s memoir, Infinity Net—a gripping book in its own right. I stumbled across those lines and thought, “Well, that absolutely sums it up.” What I’m doing as a researcher really is prowling around, going through lots of material, both to understand chronology and how things happen, but also on the lookout for scenes that encapsulate something, that I can use. I love it when I’m writing a book that has multiple characters and I find somewhere where they intersect. Or sometimes it’s just a line that’s so beautiful, or when the subject expresses something very purely in their own voice. I like people speaking in their own voice.

How much time do you spend researching versus writing?

If I’m working on a book there could be a year or two, maybe more of archival work. Then I write a draft that is really shitty. At the beginning, I care much more about trying to get the information down than particularly attractive writing. There comes a point where I feel free enough with my understanding and then I can move very quickly in terms of writing. That work in the archives is really what propels everything for me. I spend lots of time looking at the work, reading catalogues and biographies, turning up letters and diaries. That sounds kind of nerdy, but I find that sort of work ecstatically enjoyable. It’s like being a detective, following up hunches and leads.

The one quality that seems to unite all of the artists you write about in Funny Weather is this sense of being an outsider, being too weird to belong. Is that something you were conscious of while writing?

People keep pointing it out so I am becoming deeply conscious of it, yes! That’s the kind of person I am, and it’s also the kind of artist I’m drawn to. I’m not Googling "outsider artists" or "weirdo artists" and going, "Right, that one next." It’s more that I’m drawn to them by way of some sort of subterranean pulse in their work. I’m interested in finding out why they felt that way and how they’ve resisted it or responded to it by way of their own artmaking or community building. It’s interesting, to go back to your first question about the book coming out in this particular strange and frightening moment. People don’t have their friends around them, they haven’t got their family and I feel like right now this aspect of Funny Weather seems to be particularly appealing. Here’s this group of people who have struggled, presented with quite a lot of intimacy. I think people are quite open and vulnerable at the moment in how they’re responding to it.

We’re all outsiders now because we’re all unable to connect with the people we usually connect with.

Also we’re not being reassured and built back up by our friends and our communities. It’s a frightening experience to be stuck with your own resources and nothing else.

Although the book is centered on the ways art can soothe in an emergency, I got the sense that the emergency is almost irrelevant and it’s just as important to find pleasure in art during times of stability as well as unrest.

I think that’s true. I’m probably not so personally familiar with times of stability, but yes, I believe they exist! Absolutely, art can emerge from stability, art can emerge from calm, art can emerge from happiness, art can emerge from love. All of those things are possible. In this book, I was slightly more interested in people who have been adrift in some way and are trying to create that feeling of stability when it isn’t available in their personal life. For example, Agnes Martin, who suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and had complicated personal relationships, is at the same time making work that testifies to joy, love and stability. She doesn’t necessarily possess those thing, but she can still make work that testifies to their existence.

But is difficulty a necessary component of artmaking?

You don’t need to be depressed or traumatised to make work, and often those states prohibit doing anything at all. At the same time art is for many people a way of making something coherent or whole out of a sense of fracture or loss. It certainly is for me, as well as a way of reinforcing love and joy.

That kind of reminds me of the time after Donald Trump was elected in 2016, when some people’s response was, "Well, this is bad but think of the art it will elicit."

I’m disgusted by that. I hate it. That makes art feel so rarefied, like the suffering of immigrant and impoverished people is worth it because somebody who has more wealth can create great art. To wish ill on the world in order to make good art feels pretty gross. I don’t think the artist longs for the emergency. I think the artist wants a better world, and art is a way to get there. But to be longing for the emergency in order to make good art feels like the equation is backwards.

Every time I read your work, the essay you wrote in 2011 about your experience living outside for The Guardian is always at the back of my mind. As an environmental activist, you’ve always been attuned to the world as being in some sort of emergency. How do you think those experiences inform your work now?

There are two things. There’s growing up in a gay family during a very homophobic era in British history, and there’s having this terror about climate change and environmental despoliation and deciding to become an activist at a very young age. That sense of oncoming catastrophe has stayed with me through the decades, as I’ve shifted from becoming an activist to an artist. It’s still with me, the sense that we’re heading towards crisis, and I still feel compelled to do something about that. I do have a sense that the artist has duties and responsibilities. I know that’s a very old fashioned and in some ways unfashionable thing to say, but I believe it very strongly. Artists have to bear witness, both to what is happening in the world and to reality as they see it.

But does that sense of catastrophe ever feel like too much to bear? Do you ever just feel like you’re ready to ignore it?

I mean, sure! But what’s happening to the environment is unignorable. It’s like a background hum that’s slowly become so loud it’s painful. That doesn’t mean I don’t appreciate pleasure, but I am aware of the cost.

One quote in the book that absolutely stopped me in my tracks was Georgia O’Keeffe saying, “I’ve been absolutely terrified every single moment of my life and I’ve never let it stop me from doing a single thing I wanted to do.” What sort of truth do you feel she was getting at with that?

I feel like that quote is really at the heart of the book. You exist in adverse conditions, but you bloody do it anyway. Push over the border, take risks with your work. Invent what you need. I’m not a massive fan of O’Keeffe’s art but her life story knocked me out.

When Hilary Mantel told you, “The best weapon against the devil is ridicule,” some other weapons I gleaned from the book are positivity, generosity, reflection, disruption…

Very good!

I did the reading! What weapon do you find to be most useful?

Alertness and generosity are the two that feel the most powerful to me personally. I loved Hilary saying ridicule. It’s so fierce. But ridicule isn’t a weapon I use very often at all. The idea of being generous, the idea of giving things freely, of sharing resources feels to me like the most radical possibility, especially in this moment of selfishness and individualism.