Nathaniel P. is a Harvard-educated white guy in his early 30s who is just about to publish his first novel. He lives in a squalid studio apartment in a gentrifying area of Brooklyn, from which he reviews books for a respected online magazine. He’s not too bad looking, nor without charm, and all of this makes him a highly eligible bachelor—and doesn’t he know it.

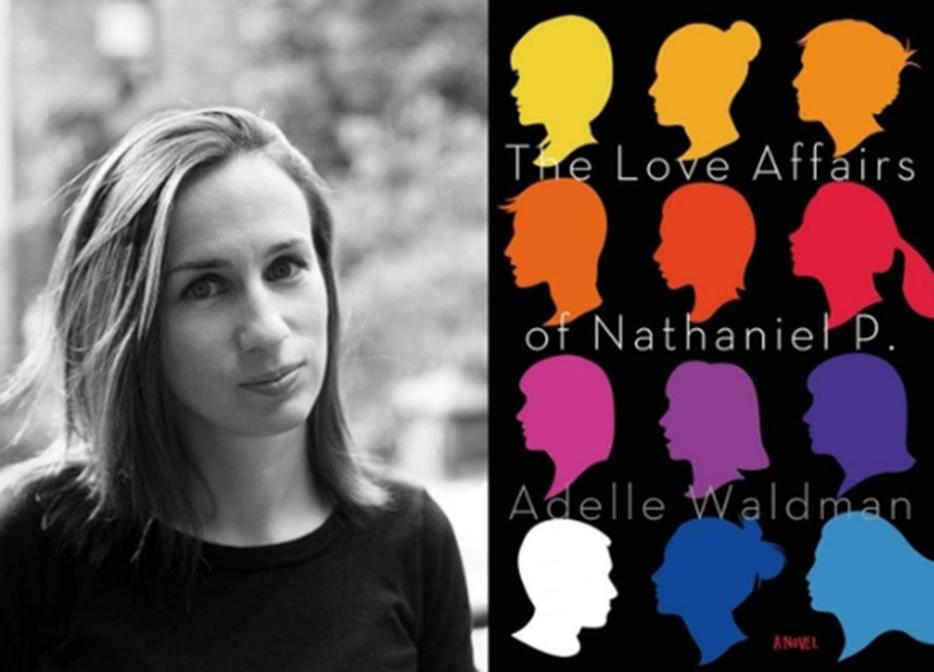

Nate is the invention of Adelle Waldman, a former journalist and first-time published novelist herself, but he is very, very familiar: a man with endless reserves of confidence who tells self-deprecating jokes as a matter of etiquette, whose guilt is partly a byproduct of self-obsession. The nerd who won, enjoying the spoils. And the spoils, of course, include women: Hannah, the smart, funny peer whom he waffles on as a girlfriend; the beautiful but callow but beautiful editorial assistant who, while callow, is also beautiful.

Waldman doesn’t sweeten her characterizations, which, for the reader, can make for a double whammy of disgust and self-recognition. While she’s friendly and unassuming in person, she writes so lucidly about the worst in people that I felt a little nervous talking to her. She calls herself moralistic, and she’s written about her love for Samuel Richardson, but the striking thing about The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. is how little she moralizes—the novel is unsparing but not prescriptive.

Though I loved the book, I found reading it a little unsettling. The longer I stayed in Nate’s head—where his behaviour made perfect sense—the deeper I fell into an empathy spiral. Were his unearned advantages his fault,exactly? Why should he settle for one arrangement when he could have as many as he wanted? How attentive should he have been to the needy girlfriend who demanded more than he felt like giving, and how much time did he owe to the woman he got pregnant, if he paid for the abortion?

I’ve banished most of these questions from my headspace, but they seemed meaningful in his—which says something about the integrity of Waldman’s imagination, as well as her empathy. It says something, too, that Waldman could write these characters without betraying her sympathies, which she doesn’t mince in conversation.

*

Did Nathaniel P. start with the ideas, or did it start with the character?

The idea basically came from reading a book by a male author, and having the sense of—I think I get what’s going on in his head better than he does. After years of dating and just sort of sitting there trying to analyze male behaviour, I thought, maybe this could add up to something.

When I started, there were things I knew I wanted in there, stored-up thoughts. Like there’s a part in the book where Nate talks about women’s writing, and he says that when you read something that you like, 80 percent of the time it’s written by a guy, and the kind of writing he likes is inherently masculine, and women can be reasonable or deep, but are usually not both. I sort of had these suspicions of things that I thought intellectual men thought. And, you know, they were confirmed.

On the other hand, I spent so long with the book that so much of it I learned as I went. I thought I had some insight into the male mind before I started, and that’s why I could do it, but it basically took me forever [to write] in part because the world looked so different from Nate’s point of view. I had to re-imagine it scene by scene.

So you had these preconceptions about how a guy saw the world, and then you had a specific male character, and there was tension between them?

I had some general ideas, but the general ideas weren’t enough; I had to flush out the details. I wanted to show the relationship with Hannah in decline, and I just thought, this situation happens all the time—a guy starts out gung-ho and then kind of pulls back, and the woman doesn’t know why. It certainly happens too with the genders reversed, but I was interested in it this way. And I knew this situation, I’ve seen enough that I thought, I’m going to dramatize that, and come up with a plausible account of all his feelings. It’s not going to be as simple as he’s just an asshole and he just wants to hurt the woman as much as possible.

Sympathy for the devil.

Right. But I realized there was a lot, specifically, that I didn’t know. The order of scenes, the decline of his relationship with Hannah—it just wasn’t inherently obvious. It’s like, Hmm, should the awkward blowjob come before or after the boring dinner? If I were writing a book about a bank robber, and he robs a bank, and then the police chase him, and then he goes to jail, it would be very logical. But trying to figure out a way to make it feel plausible and not as boring for the reader as it was supposed to be for Nate. Also, I thought that would make the reader weirdly too sympathetic with Nate, and not sympathetic enough with Hannah.

It’s funny. I don’t know that I sympathize too much with Nate, but I know that I don’t sympathize with Hannah. And the reason I didn’t sympathize with Hannah is because I saw so much of myself in her, and it’s all stuff that I hate.

Interesting.

And the fact that Nate is on to her—like, he knows that she’s one of those women who doesn’t want to be one of those women. It was kind of like, Oh. Shit.

Ok, well, I do think Nate has an advantage over most men, in that when I made him think these mean thoughts about women—which he does all the time—he had access to all of my fears and insecurities. I made Nate think exactly what I most feared a guy would think, you know what I mean? [Laughs] So I think the things he says about women are more incisive than what a real guy would think. But that was sort of my fear—what if a guy could see through me in these types of moments?

There’s a weird relationship between Nate and me, where he has weird access to my mind. And some moments I almost feel guilty, I feel like I violate his privacy. Which is insane. [Laughs]

But on the other hand—and I totally get different responses to this, all the time—I have a lot of sympathy for Hannah. Every single thing she does I can relate to.

I can relate to her too, but I think that’s the problem—all the stuff I hate about myself, I saw in her. And seeing that through the male perspective especially was sobering.

But did it ever make you, I don’t know, hate Nate all the more? Ironically, I wanted to problematize Nate’s reaction to her, because I sort of hoped the book made Hannah’s reaction understandable: she’s kind of pulling her hair out and trying her best, and there’s nothing wrong with the fact that she winds up caring for Nate and feels confused when he ends up pulling back. I wanted to present something that is sympathetic, even though it’s a challenge because one part of being human is that we don’t want to sympathize with the person who has less power. It’s uncomfortable. And Nate has more power. But to me, Nate sort of fails in terms of the human test, in terms of empathy, and self-awareness. So I sort of hoped that although Hannah is the one who’s getting hurt, Nate looks worse in the end.

It’s funny. I don’t particularly like Nate as a person, but I could also understand why he did what he did, with the advantage he had. Do you think you would do any differently if you were a man?

I hope so, in certain ways. There are a billion things that I totally relate to about Nate—things that certain people get annoyed by and find really pretentious. I relate to his intellectual life, I relate to his ambition, I relate to his relationship with his parents. But I think there’s a way he’s able to hide from himself his own role in someone else’s unhappiness.

Another thing—and this isn’t a matter of moral responsibility—but if Nate were writing the book about himself, I think it wouldn’t look like the book I wrote. It would look like a book all about his rising career trajectory, with a few sort of glamorous sexual encounters thrown in, about his crazy adventures in New York. And he’d edit out that stuff about evaluating women on a scale of one to 10, and wondering what his friends think, just all these moments that are kind of unflattering to him and make him seem shallow and ordinary and just pretty unappealing.

Ultimately, he’s less interested than I was, before I was married, in finding a meaningful connection with a person whom he not only is attracted to, but respects, in a deep moral, intellectual way. I think if that meant more to him, his behaviour would be very different. But he’s got a kind of reflexive sexism that allows him to think of women as more interchangeable than I thought of men. It’s not just a moral accountability issue, it’s kind of who he is. I don’t think it’s very appealing.

I think for Nate, it’s almost an impossible standard to expect a woman to be his equal. It would be unchivalrous to judge women too harshly. [Laughs]

I wonder, in general, how much of this kind of sexism stems from a genuine disrespect for women, and how much of it springs from having more options and a better chance of it all working out okay. And if you have that advantage, what are you going to do—sit on it?

That’s true. But I think, at least by my standards of being a good person, as opposed to just a justifiable person—there’s a line from Samuel Johnson, I think, that to be a magnanimous person is to be unwilling to do something that will bring harm to another person, regardless of whether it will benefit you or not. I think our culture can justify looking out for one’s own interests and maximizing one’s own well being, which I find a bit ugly—to just be thinking of what one’s own options are. And not just ugly but also antithetical to the kind of tenderness that is part of being happy in a relationship, and also being happy in life: having a different attitude toward other people that’s less concerned with self-maximization.

In the book, Nate develops this connoisseur-like attitude toward women, where he’s calculating the market value, in your words.

Although, I say that he is not doing it as much as his friends.

Oh yeah. Jason scared the hell out of me.

I know, I know. But he’s kind of the guy that you wouldn’t date anyway, because he’s sort of weird with women.

But the idea of market value. I don’t know if this is a modern phenomenon, but it feels easier to succumb to, since the kind of relationships we get into are less prescribed—it feels like relationships are more transactional, easier to think about in terms of apartments or restaurants.

Yeah, I absolutely think that. At the same time, I don’t think this kind of transactional thinking is actually new. You see it in Jane Austen novels, or George Eliot novels, the less attractive characters are thinking about romantic partners in terms of maximizing what they can get. Probably most famously in Sense and Sensibility, there’s the Dashwood women who are the heroines, and their brother who thinks things that are funny but dark about how wealthy a man they can attract based on their attractiveness. And one of the sisters has lost her bloom, and a year ago she could have gotten a man worth a thousand pounds but now she’d be lucky to get a man who brings in 500 pounds a year. Which I just take as an indication that not all of this is new—some of it, to me, is just a function of individual character. Our culture can reinforce it in a lot of ways, but it’s a way of thinking that’s always available to human beings, and maybe a mark of bad character.

I wanted Nate to not be the worst offender, because if I made him too bad, the book loses interest; he’s an asshole, and it’s easy to just judge him. Also, at times, he says about women who are interested in him, that he doesn’t feel as sympathetic to their plight as he might because he suspects them of having a transactional attitude toward him. They’re interested in him because he’s coming up in the world, and how sympathetic to that does he really need to be? And I think he’s right about that. It’s not that the women are all selfless creatures who just love him in some noble way, and he’s just heartless. Both sides can be guilty of transactional thinking.

Something I keep coming back to are the onion layers of privilege on display in the book. This comes out in Nate’s essay, and when he says that “it tormented his conscience to see a stooped Hispanic lady scrubbing his toilet.” Thinking about privilege becomes a form of inertia.

Right. I’m not sure if this is what you’re asking, but in terms of writing about people who had privilege, I thought it was a valid subject. There’s this [idea] that privilege makes you an unsuitable subject for fiction, because the only real struggles are economic. Personally, I’m alright if my novel doesn’t tackle a lot of the issues that I genuinely care about. I often read fiction because I care about these emotional struggles, and that doesn’t excuse the need to make political decisions or do things politically, but I don’t need them in fiction. Not everyone feels this way, and I’ve certainly gotten [that] criticism of the novel—who cares about a bunch of privileged people and their mating habits. I personally do, and I think it matters.

But that said, I’ve never gotten farther than the problem you’re describing, where I think often times a sense of one’s privilege can lead to nothing but a sense of guilt about one’s privilege. I don’t feel like I have the answer to that. I’m sympathetic to Nate’s feeling of being a little hamstrung, where he’s aware of his privilege and all it leads him to do is feel guilty about it. I can relate.

I can relate as well. I had a similar feeling when I read “The Semplica Girl Diaries” in the last George Saunders book. Whatever the characters are going through, their privilege sort of hangs like a shadow over the narrative, and I think your book weaves that in well.

Oh, good, yeah I’m proud of that, because I do think it’s a real factor, that awareness of privilege. Also, this is a tangent, but one thing that struck me as interesting about women writing from the male point of view is that, [in terms of] gender privilege, I felt like there were ways in which Nate thought about his career, and the way he presented it to himself and to others, that I didn’t quite relate to as much. I don’t want to paint myself as a victim in any sense, in many ways I’m super lucky, but Nate, being male, and having gone to Harvard, he fit the world’s image of what an up-and-coming intellectual should look like. And I think he takes that for granted, and other people he meets take that for granted, and I thought that was interesting.

The way Nate interacts with women in his dating life, is that political to you? Is it a feminist matter, does it even make sense to think about it that way?

I think so, to the extent that sexism plays into it. I always get wary of analyzing the book too much, but I’m just going to do it now, maybe because I’m tired of saying the same things I’ve already said. [Laughs] So in the book, there’s a flashback chapter to a woman named Elisa, who’s very beautiful. He has a relationship with her for about a year and a half, that’s really—about 60, 70 percent of his interest has to do with the fact that she’s very beautiful. And he sort of realizes early on that he doesn’t really respect her, doesn’t really respect her writing, thinks she’s very immature, entitled, but these aren’t disqualifying factors for him. And I don’t think that’s as atypical as I wish it were of—maybe not all men, but some men. And I think that is related to a kind of sexism, that sense that what he’s looking for in a woman is not necessarily someone he can respect. When he finds that to a degree with Hannah, he thinks it’s neat—but that’s just sort of weird, to me, as a woman, that he thinks it’s neat rather than essential.

So I think there’s a political element there. That said, I don’t know if I think it’s something that can be solved from above or legislated. I think the worst of Nate’s sins are in his private thoughts.

Has it been disturbing hearing from male readers who identified with Nate?

Well, I’m in such a weird position, because my vanity as an author is so pleased by that. But the extent to which men are reading the book is really heartening, I’d say. Just yesterday I had this Twitter conversation with a guy who was saying he felt like men needed to read this book, because it laid out feelings they can’t articulate to themselves. But he felt it was being marketed too narrowly as a Brooklyn literary book, and that it had to get to the wider population of men in America. And as an author, couldn’t agree more! Everyone should read the book. [Laughs]

On the other hand, what I like about that, and what I’ve also felt about the reaction I’m getting from men—they are relating to Nate, but they’re not relating to him with a sense of pride, like, Finally! Someone articulated this and I’m so glad, now I feel so vindicated. I feel like they’re relating with a sense of, This is not stuff I’m super proud of. I have a lot of men saying they winced or cringed with recognition, which might be kind of useful—if they feel a little bit of shame in that recognition, maybe it will prompt them to do some of the thinking that I wish Nate was doing.

I feel like Nate evades a lot, in terms of his relationship with Hannah. And when he does feel bad, he just wants to feel better, so he’ll hang out with a friend, someone who will reflect back the self he wants to feel like. I think we all do that, I think it’s very human. Nate comes close to thinking about himself and then ultimately avoids it. But in the end he’s punished for it, I think. On the surface, it looks great. But on another level he looks a little pitiable and foolish, he looks like he’s failed to learn from experience, and he looks a little clueless. And for someone like Nate, with his ego, that’s kind of damning.

I hope that men who relate to Nate also feel that, a little bit—that there’s a penalty. It may not be a worldly penalty, in terms of not being successful. But a human penalty in terms of not being the person they want to be.